By the late 50s, the Beat Generation had transformed San Francisco’s North Beach into the hippest neighbourhood on earth. Embracing the ethos of sex, drugs, jazz, and Eastern philosophy, a coterie of artists, musicians, writers, and poets stood at the vanguard of the modern counterculture. As the community grew, they expanded their base, finding shelter in the quaint and affordable homes dotting the Haight-Ashbury district across town.

By the mid-60s, beatniks and hipsters began to evolve into a new generation of hippies. Adopting a bohemian spirit, hippies were even more far out as they rode the psychedelic wave to expand consciousness to dazzling new heights. With the explosion of rock music came a new vibe, one that demanded new frequencies to tap into the mind-altering powers of art. In addition to marijuana, hippies began experimenting with hallucinatory drugs like shrooms and LSD.

First synthesised in 1938 by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann, LSD hit the market in 1947 and was touted as “a cure for everything from schizophrenia to criminal behavior, ‘sexual perversions’, and alcoholism.” By the 50s, the CIA swooped in, purchasing vast quantities of LSD for the top secret 20-year Project MKUltra — which was later revealed in 1975 to have conducted experiments on military and government personnel, sex workers, mentally ill patients, and members of the general public without their knowledge.

By the 60s, counterculture figures like writer Aldous Huxley, psychologist Timothy Leary, and “psychedelic missionary” Al Hubbard were openly advocating for LSD. The drug’s rising popularity invariably led to a backlash by the state. After California outlawed LSD in October 1966, the left mobilised, organising the historic Human Be-In rally at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

On January 14th 1967, over 20,000 people gathered on the Polo Fields to hear poet Allen Ginsberg, mystics Alan Watts and Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass), activists Jerry Rubin and Dick Gregory, and local rock bands including The Grateful Dead, Big Brother and The Holding Company, and Jefferson Airplane perform. Making his first San Francisco appearance, Timothy Leary took the stage and memorably told the crowd to “Turn on, tune in, drop out.”

Revellers did just this, dropping “White Lightning” LSD that “underground chemist” Owsley Stanley produced for the event. Speakers encouraged attendees to question authority while advocating for civil rights, women’s rights, communal living, ecological awareness, higher consciousness, and psychedelic drugs. Stunned by what they were witnessing, the national media was set aflame, and the word of a New Left spread like wildfire.

The burgeoning hippie movement quickly picked up steam on May 13th when singer Scott McKenzie released “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” to promote the Monterey International Pop Music Festival the following month. Giving a voice to flower children, the song was an instant hit, reaching the Top 10 in July.

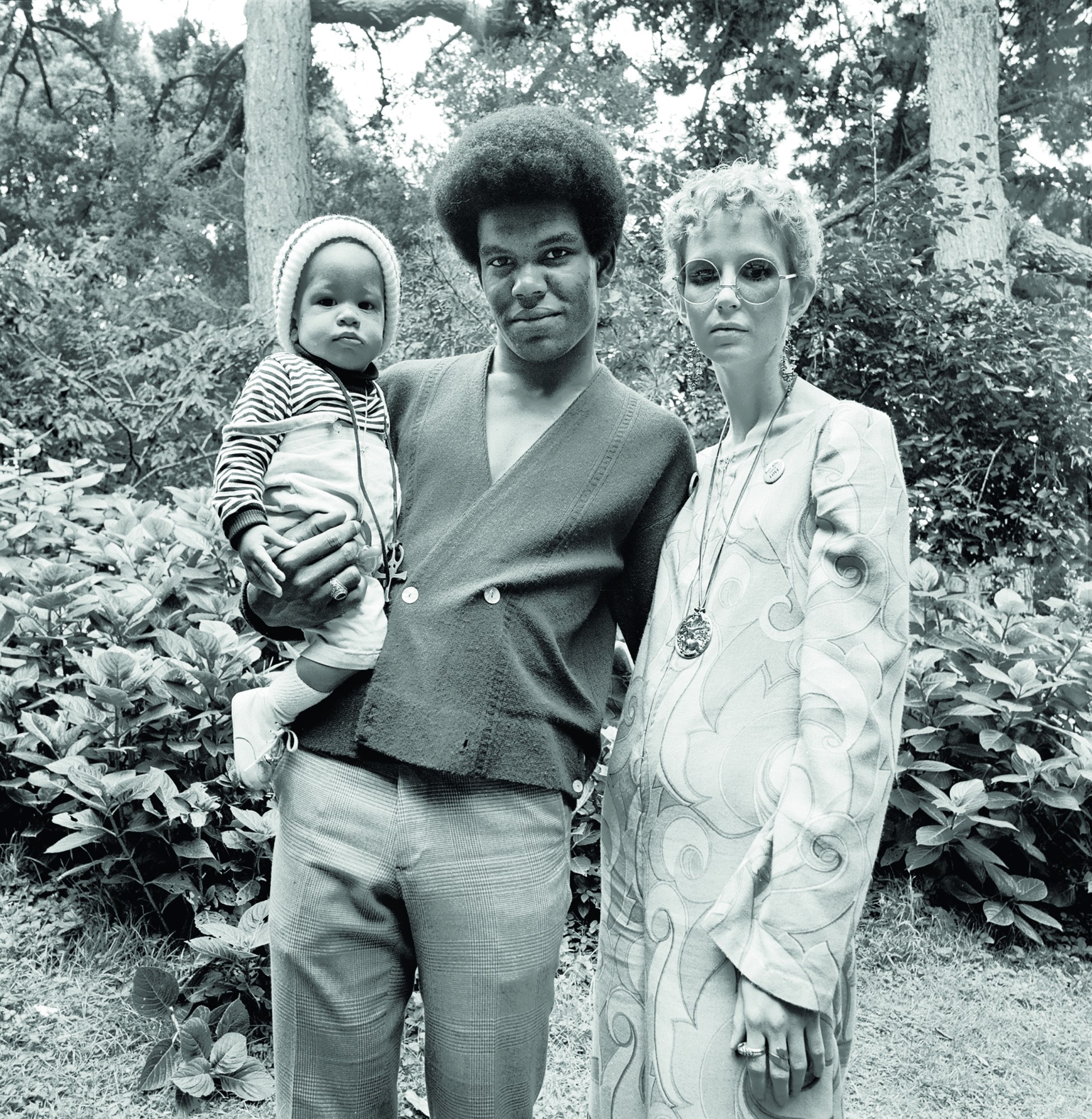

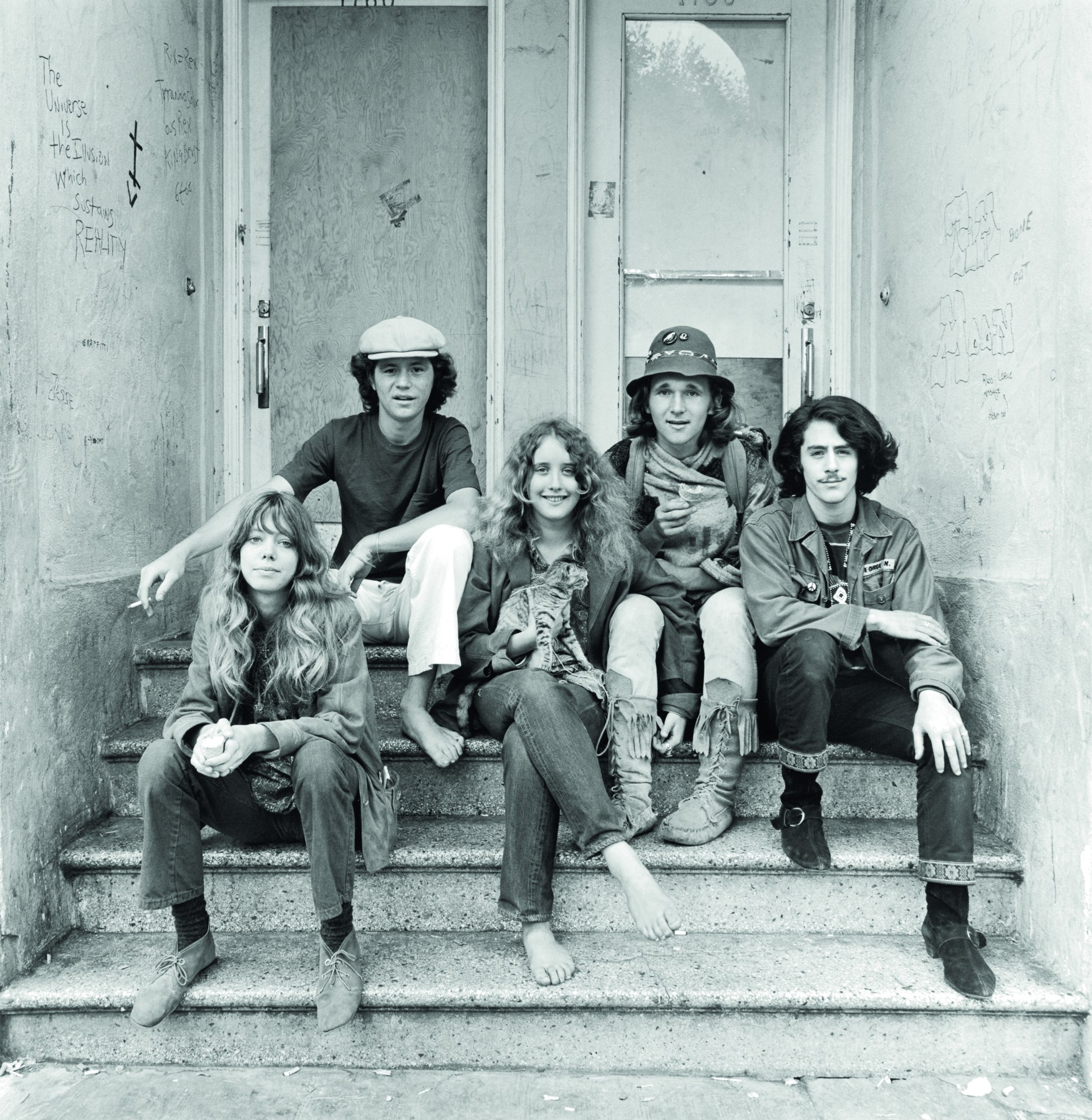

By that time, over 100,000 runaways, high school and college students, and young adults had descended on San Francisco, making a beeline for the Haight, and kicking off the Summer of Love. Filled with charming 19th-century multi-story wooden homes that survived the fires following the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the Haight readily became the perfect site for communal hippie life. Musicians like Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jerry Garcia, Grace Slick, and their bandmates settled into the neighbourhood, adding to its allure.

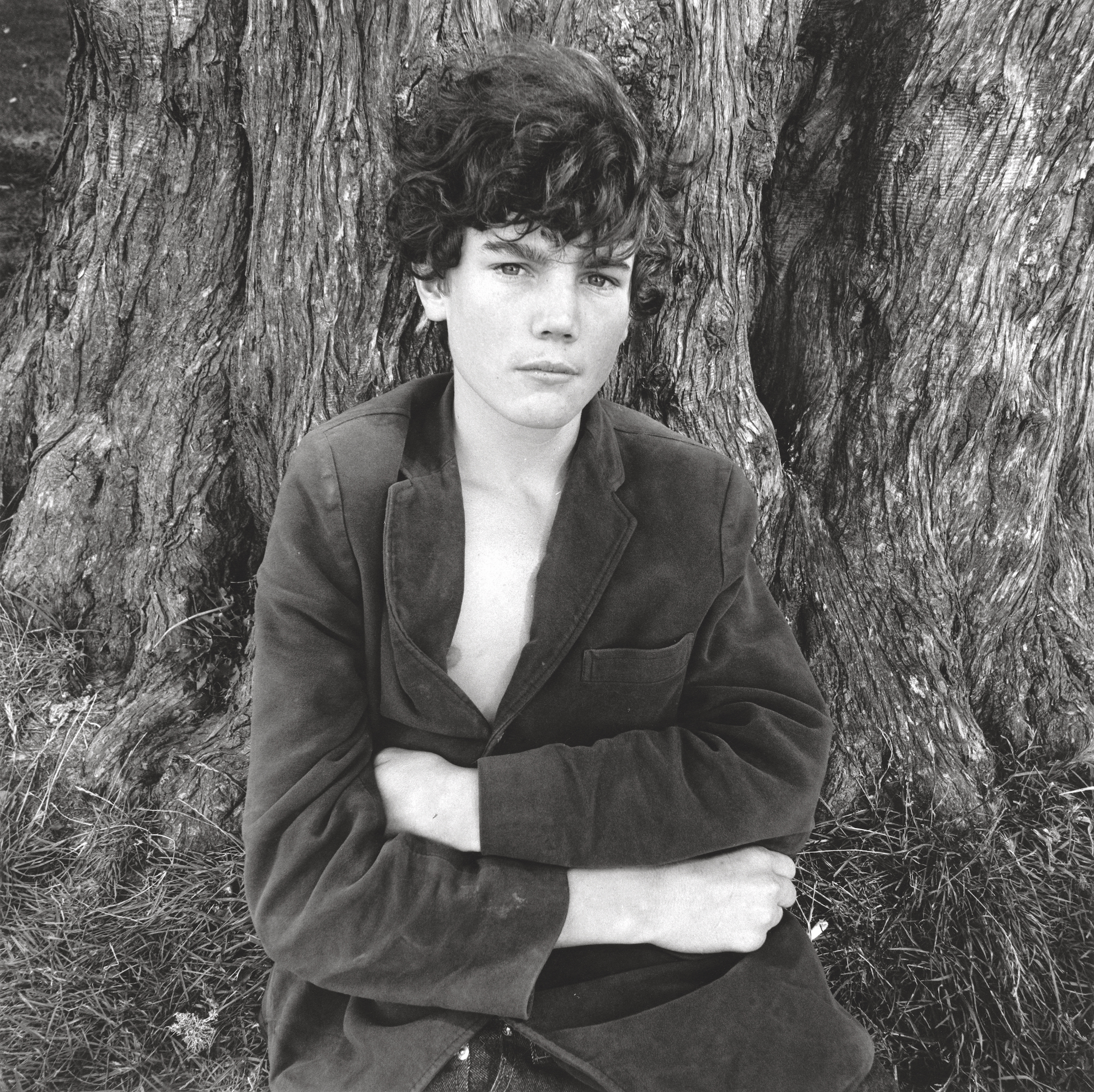

Photographer Elaine Mayes, then in her 20s, became a resident of the Haight during the Summer of Love — nearly a decade after she first moved to San Francisco. Although she had studied music at Stanford, Elaine was unsure how to turn this passion into a sustainable income, so she shifted her attention to painting and then to photography — rather than become a housewife and mother, a path many young women of the era were guided to pursue.

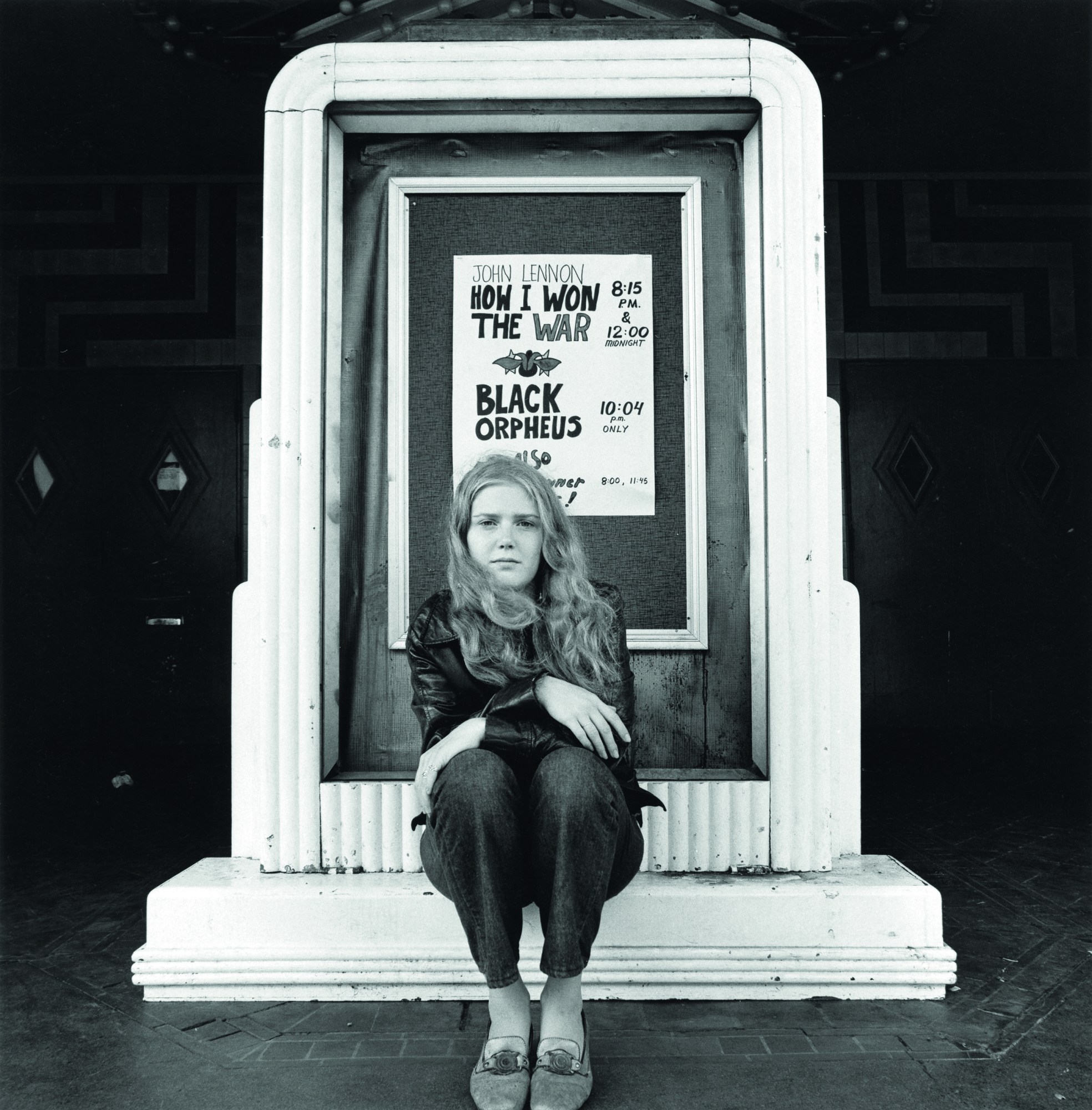

“I didn’t want to stay at home. I wanted to go out in the world and do something that was important,” Elaine says. Elaine carried a small handheld camera, which allowed her to photograph everywhere. She began working with various designers and magazines as a freelance editorial photographer, which allowed her to pursue her own projects, most notably a series of documentary portraits collected in the new book and exhibition, Haight-Asbury 1967-1968.

The project began organically, following an unexpected route that was born one night in early June 1967 when South African jazz musician Hugh Masekela knocked on her windowpane searching for a friend. Elaine gave him directions, but Hugh was unable to find the place, so he slept outside that night. The following day Elaine hopped on the back of Hugh’s motorcycle and the two rode to the Fantasy Fair on Mount Tamalpais, where new bands like The Doors took the stage.

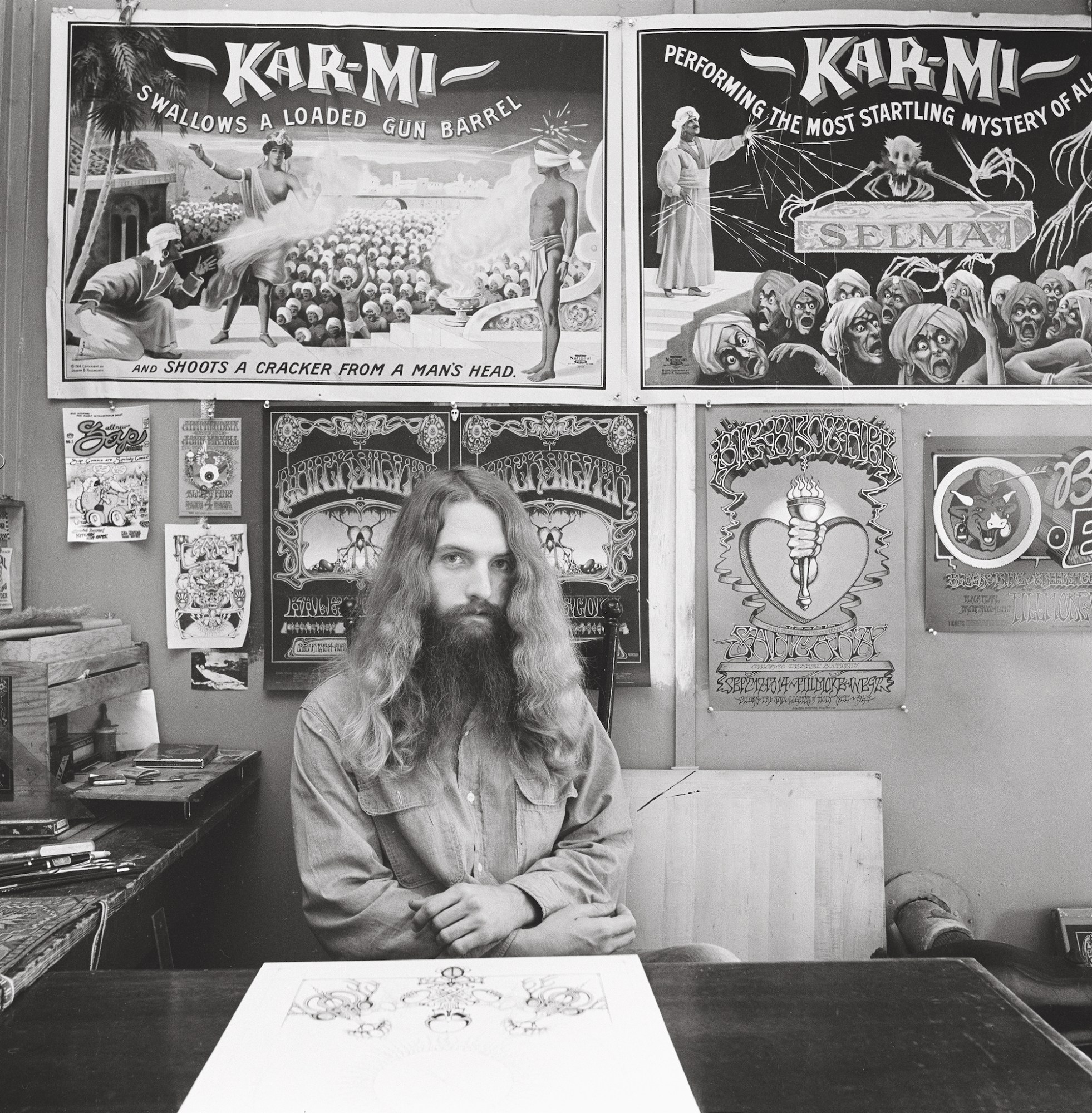

After photographing the band, Elaine met Jack Leahy, a stalwart of the San Francisco music scene. Jack, who had a company that made posters for the Fillmore and Avalon Ballroom, asked Elaine if she had any photos of the Haight. Not yet a resident, Elaine told him she had been going over on weekends to photograph the scene. She later showed these pictures to Jack, who invited her to move into his commune on Central Street — the first of three places she would live in the Haight.

“Everything was an adventure for me then, and so a bunch of people moving into a three-story house and trying to function was not a familiar scene. It was brand new,” she says. “I lived in a room on the third floor with a bed and no other furniture. I didn’t really know the other people in the building, but I wanted to be where the action was.”

Being a freelancer, Elaine’s time was her own and she began walking the streets of the neighbourhood making photographs. “Maybe the most exciting thing was walking down the street and bumping into Diane Arbus,” she remembers. “I knew who she was because I had met her in New York. She was just standing there. I invited her back to the commune, and my roommate gave her some pot. She got stoned and it freaked her out.” Unsure what to do, Elaine drove Diane around the city and bought them ice cream cones, hoping to bring her back down before Diane had to photograph topless dancer Carol Doda for Esquire magazine later that afternoon.

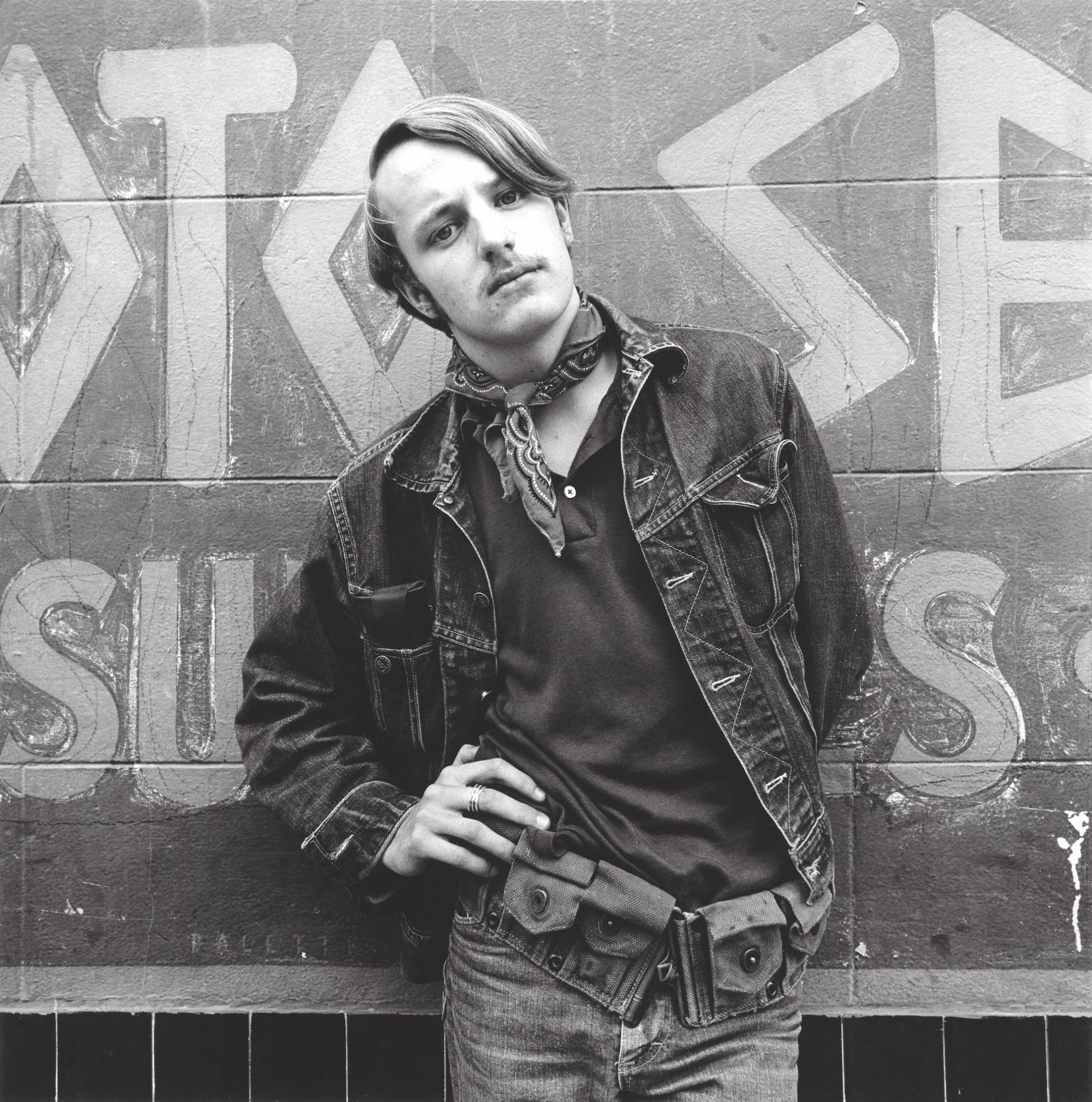

Elaine came to realise that the Summer of Love and the radical transformation of the Haight was driven by media-constructed narratives. Rather than follow the story-driven approach of photojournalism, she began making documentary portraits of the people she encountered on the street with the same curiosity, tenderness, intimacy, and respect that Diane Arbus brought to street portraiture. After posing for the long exposure, sitters were invited to caption their pictures and sign a release form, which everyone did, with the exception of a few draft dodgers.

‘Elaine Mayes: The Haight-Ashbury Portraits 1967-1968’ is on view through 4 March 2023 at Deborah Bell Photographs in New York. The book is published by Damiani in collaboration with FotoFocus, and edited – and with essay – by Kevin Moore.

Credits

All images © Elaine Mayes