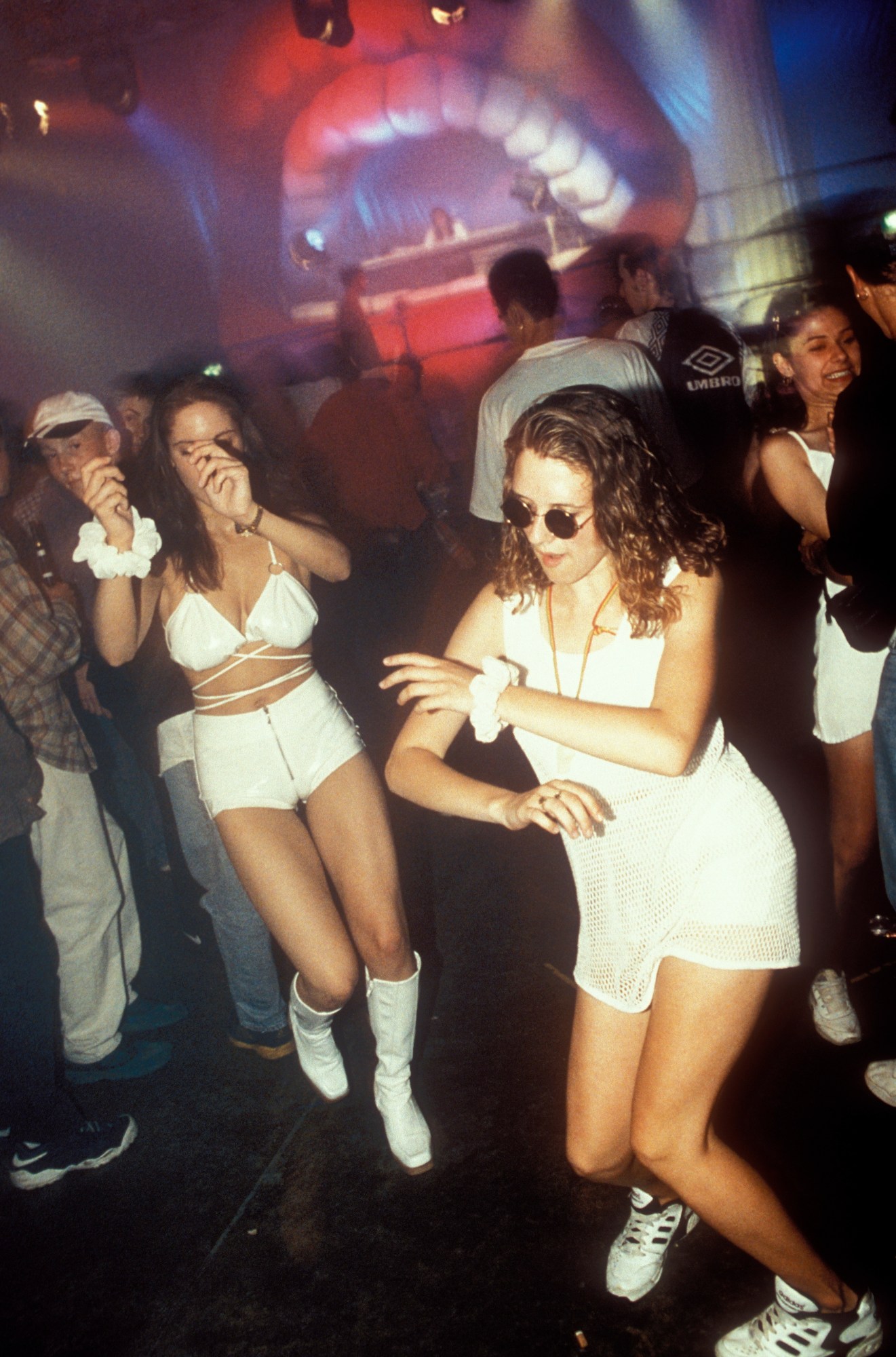

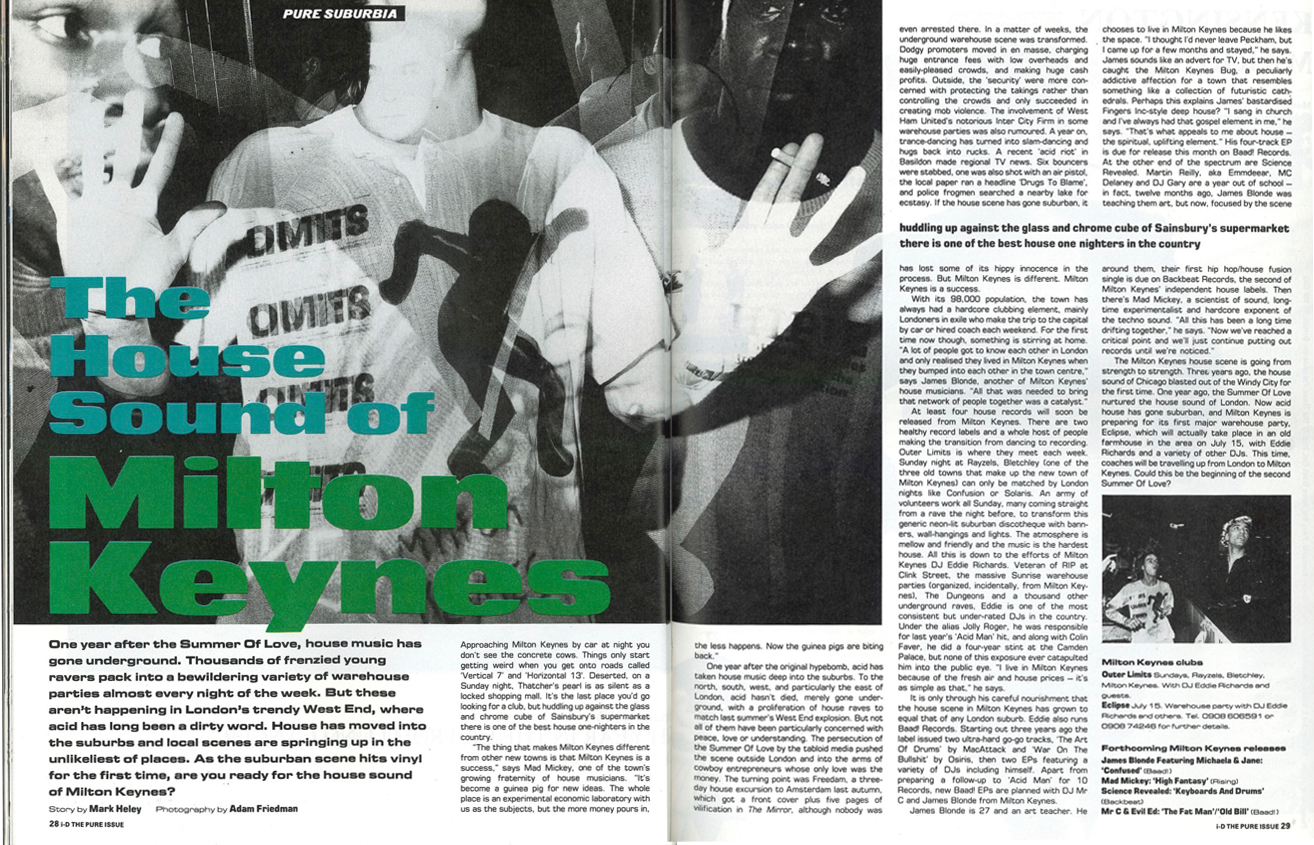

“One year after the Summer of Love, house music has gone underground,” proclaimed a 1989 issue of i-D. “Thousands of frenzied young ravers pack into a bewildering variety of warehouse parties almost every night of the week. But these aren’t happening in London… house has moved into the suburbs and local scenes are springing up in the unlikeliest of places.” The subject of the article? Milton Keynes.

Situated about 50 miles north-west of London, the UK town was built in the 1960s as part of a not particularly sexy but much-needed plan to relieve housing congestion in the capital. While today it is perhaps best known for its many roundabouts, Xscape and concrete cows, it was a whole other story back in the late 80s and early 90s: Milton Keynes was a nightlife destination. As the scene pivoted from illegal to licensed raves, MK was a beacon for hedonistic music fans who travelled from up and down the country to attend the legendary Dreamscape 1 rave, before the venue was officially opened as a 3500 capacity club, The Sanctuary, in 1991.

Taking over a disused industrial space on the outskirts of town, The Sanctuary hosted 12-hour nights including Fantazia, Helter Skelter and Hardcore Heaven, with artists like The Prodigy and Goldie passing through its doors up until it closed in 2004. With an IKEA now residing on the club’s resting place, writer and creative consultant Emma Hope Allwood — who grew up in the town — decided to explore its forgotten history. Marking 30 years since that first Dreamscape 1 night, Sanctuary: The Unlikely Home of British Rave shines a strobe light on the overlooked importance of Milton Keynes in music history. Full of photography, video, merch and other rave ephemera, the exhibition is open at MK Gallery Project Space until 23 January 2022.

Keen to discover more, we spoke to Emma about her own experience of clubbing in MK, discovering her dull suburban hometown had a hidden past, and the music that soundtracked her curation process.

You grew up in MK. How do you think the town shaped you?

Milton Keynes was not a bad place to grow up, but I just knew there was more out there for me than what it could offer. In a weird way, I’m glad I had to endure the tedium of teenageerdom in suburbia, to have a job in the shopping centre (and be told by my male retail manager that I wasn’t smiling enough) and to see the things London had – like American Apparel – as highly exotic. It gave me a desire for escape, independence, and to make my world as big as possible.

What did your own experience of clubbing there look like?

There’s a whole genre of YouTube videos which are like: “you’re in the bathroom of a club in 2010”, where you basically hear the muffled sounds of Taio Cruz’s “Dynamite” playing through the walls: that’s pretty much it. My experience of clubbing in MK was putting on a dress and heels, downing 3-4-1 Jägerbombs at a retro-themed, sticky-floored club called Groove, then going into the vortex of Oceana to get lost amongst blue lights playing chart hits, probably attempt to quash some kind of jarring existential dread, sleep in a friend’s bed, and then go to school the next day. It was how we hung out and had fun, but it wasn’t really me.

So when and how did you first become aware of its rave history?

It wasn’t until I’d moved to London and I was working at a magazine, researching rave flyers. I came across the flyer for Dreamscape 1, the first rave ever held at the venue. The flyer is very striking and features this woman’s face emerging from a green grid of light. I was totally taken aback to realise the address of the venue was in Milton Keynes – I’d never heard of the club (it closed when I was still in primary school) but I was fascinated. Not much seemed to really exist about it online, so it occupied this space of fascination; a scene that I’d missed, another world. Milton Keynes is also seen as this totally cultureless place: finding that flyer was proof that something incredible had happened there. This exhibition is an attempt to show that.

How did Milton Keynes end up becoming such a nightlife destination?

One major factor is that MK is towards the middle of the country and very motorway accessible, so people would travel from all over the UK — literally pile in the car from Devon. It’s great watching footage of ravers queuing outside The Sanctuary and hearing accents from everywhere. Also, before the club, there were a couple of important locals: Evil Eddie Richards, who was an influential house DJ and started the UK’s first DJ agency, meaning there was a steady flow of artists coming to MK from Detroit and Chicago, which are of course the cities that started it all. As well as running an influential club night, Outer Limits, from 89-90 in a club called Rayzels (earning a feature in i-D!) he booked the DJs for the infamous Sunrise raves, which were started by a group of MK locals who were bored of the local scene and were inspired to do their own thing by trips down to the infamous London club night Shoom.

You began the project with a call out for local rave ephemera. What was the response like? You must’ve met some interesting characters?

The response was amazing. Working with The Museum of Youth Culture, we scanned and photographed hundreds of submissions to be preserved in their archives. One of the most incredible things that turned up (that I unfortunately couldn’t include in the exhibition because I didn’t have space) was a 2m long window from the club with the logo on it — a woman had gone down while it was being demolished and asked if she could have it, which I think speaks to how fondly people remember their nights there.

Tell us a bit about your favourite discoveries during your research / curation process.

It was probably just driving around the country and meeting people, waiting while a guy got his horn out of the loft (which I display in the exhibition on a plinth, like a totemic artefact), or sitting on someone’s bedroom floor while their kitten played in stacks of flyers they’d kept for years. Getting a road sign (the club’s address was iconic, so these do go missing!) from someone’s garden or going through library archives or folders of newspaper clippings – like the one story about a raver who’d had to be rescued from the roof of the nearby Petsmart very confused after a rave.

Finally, presumably your work on this project had an incredible soundtrack. What’s your favourite track that we would’ve found blaring out of the Sanctuary speakers?

This iconic 1995 Fugees remix by DJ Zinc!

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more about nightlife.