It’s Thursday afternoon and I am talking to my play partner about what we’re going to wear to Klub Verboten, one of London’s biggest kink, BDSM and fetish events. Each month, it caters to over a thousand primarily queer people of various gender identities and ages. We always plan outfits in advance – but this time we have to factor in the moralising gaze of Tower Hamlets Council. Last week, the council contacted E1 — the party venue — ahead of Friday’s event, seeking to prohibit “nudity and semi-nudity” and threatening to revoke the venue’s license otherwise. With the definition of “nudity and semi-nudity” being both incredibly obscure and violently binary (it includes exposed nipples for women but not for men), we decide that we’ll both go for full-coverage latex catsuits. Under the thin layer of skin-tight black latex, we hope that our bodies will not be considered semi-nude – and therefore not a threat to public decency and wellbeing.

At the core of the issue faced by Klub Verboten lies licensing legislation for sexual entertainment venues. On paper, SEV licensing is intended for sex cinemas, strip clubs, and sex shops. It is hardly the right category for a kink and fetish event, but the only one available to apply for. Established in 2016, Klub Verboten events usually consist of a sizeable dancefloor with booming techno and a separate playroom where one can safely and consensually practice BDSM and kink: from bondage to impact play, power exchange to what is typically defined as “sex” in vanilla terms.

The dress code for the event – latex, leather, PVC, chains, lingerie – is informed by the history of the fetish community and fuelled by members’ creativity. In essence, it’s not that different from London’s many gay raves with darkrooms – only with a more elaborate dress code and BDSM furniture. This is why it’s worth noting that while Klub Verboten might be the council’s first target, it won’t be the last. Crossbreed, a queer rave and kink event which runs every Sunday at Colour Factory has also been contacted by the council, and is currently in conversation over the nature of the event with regard to SEV licensing.

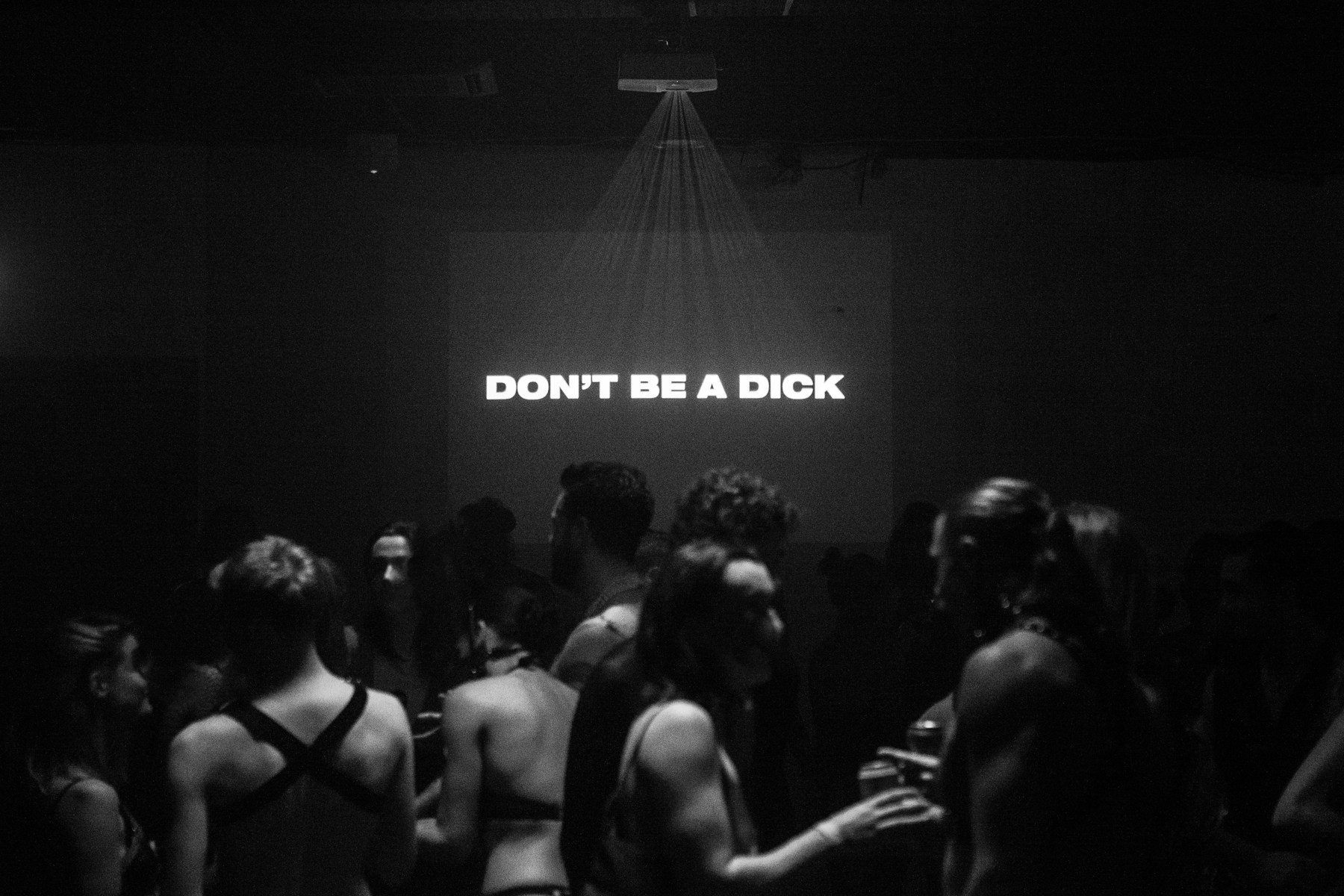

Faced with this threat, it’s more important than ever to remember what these spaces actually mean – a task that’s been aided by a rapidly growing campaign under the hashtags #savekinkspaces and #savequeerspaces. I remember the first time I stepped into a kink event. It was Klub Verboten’s first party after the easing of COVID-19 restrictions in the summer of 2021. I didn’t have much fetish gear, so my outfit consisted of a few layers of fishnets and a corset from Etsy. As I stood in the corridor flooded with dim red light, it felt too good to be true after two years of isolation. People were beautiful, excited and giddy in their kink get-ups: leather trousers, PVC bras, latex hoods. A person dressed as an otherworldly latex doll towered in the middle of the room. I saw someone getting whipped – before that I had only heard a crack of the whip in films. None of the above seemed weird, scary or unusual. There was a warm shared sense of unity, care and vulnerability – the fact that everyone has brought their most private self here, the only place where it could be properly expressed and appreciated.

Entering a kink club has given me a sense of freedom I’ve never felt before. Growing up as a woman, you are constantly shamed and punished for expressing your sexuality. Even after you’ve outgrown the shame, the traces of it remain in your body – in how you move and what you wear in public space. As women and femmes, gender non-conforming and non-binary people, the desire to avoid catcalling, groping or abuse inevitably impacts the way we dress and behave. At Klub Verboten, I could walk through the space wearing a sheer mesh dress, tight latex or even be topless, and feel powerful, sexual and safe. With multiple layers of safeguarding in place (membership system, vetting, monitors, the ability to immediately flag inappropriate behaviour), an environment that is consent-focused and prioritises safety and good communication is actively cultivated – something that is far from the norm in wider society.

Kink, BDSM and fetish clubs are an integral part of cultural and queer history. Memories of them are woven into cityscapes – Skin Two, Der Putsch, Rubber Cult, SWEAT in London to name just a few. They have always been spaces of radical freedom which unavoidably attracted active condemnation of conservative powers. In the early 90s, London’s leatherdyke S/M night Chain Reaction (frequented by the Rebel Dykes crew) was stormed by a group of balaclava-clad protesters who deemed sadomasochism anti-feminist. Catacombs, the cult gay BDSM and fisting club in San Francisco, was shut down in the early 1980s when the leather community was largely blamed for the onset of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Indeed, so-called sexual deviants and perverts have historically been an an easy target for moral panic. What that means that the level of community care and self-regulation in the BDSM circles has often reached inspiring heights. The oldest set of play party rules I’ve held in my hands was from a 1989 party by the Society of Janus, a San Francisco-based BDSM education and support group founded in 1974. We are now aware of the importance of this history, and there are even institutions dedicated to its preservation like the UK Leather and Fetish Archive. Today, events like Klub Verboten work openly and transparently to put the safety of their community first – despite the progress this speaks to, however, they still face age-old stigma against sexuality, queer people and kink.

You might ask: why not do these things in private? Why not engage in your strange sexual acts behind closed doors? As a queer person who grew up in a conservative country, I am familiar with the narrative of “doing things behind closed doors” – of being allowed to be different only if you keep it secret. I know that because I am a queer, non-binary person, public space will never be totally mine. But this is exactly why queer and kink spaces are so important – they allow people to exhale, to feel accepted and worthy of love and respect just like everybody else.

The truth is, kink, BDSM and fetish are not for everyone. This is why Klub Verboten is a ticketed private event. But the issue at stake is much greater than a single event, or the community it caters to, being targeted in a certain London borough. The issue is the existing stigma against sexuality which harms the most vulnerable first: LGBTQI+ people, sex workers (who are continuously losing safety in the workplaces due to SEV licensing), young people who are unable to have an open conversation about sex.

Alternative sexual imagination is political. Finding pleasure as a marginalised person is political. Learning about queer sex when it was excluded from sex education is political. This is what the new generation of LGBTQI+ people are looking for at spaces like Klub Verboten. We might get up to some filth – but we also want to create an open, informed, respectful conversation about sexuality. If we’re deemed perverts for that, so be it.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on nightlife.

Credits

Photography Zbigniew Tomasz Kotkiewicz.

Images courtesy of Klub Verboten.