This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Earthrise Issue, no. 368, Summer 2022. Order your copy here.

There is a sense of poetic continuity that runs throughout the work of fashion designer and artist Grace Wales Bonner. A feeling that everything – from her fashion presentations and publications, to her exhibition A Time for New Dreams at the Serpentine Gallery in 2018 – exists in a single burst of language bound between the same two covers.

Together they form an abstract geography, where a journey across the Indian Ocean in the 16th century, a collar or sleeve in a painting, the writings of Gary Fisher or Ben Okri, and a sound heard in passing on a stroll through South East London hold one another, adrift in the same seas. It is a form of storytelling that gathers material from everywhere the trade winds blow.

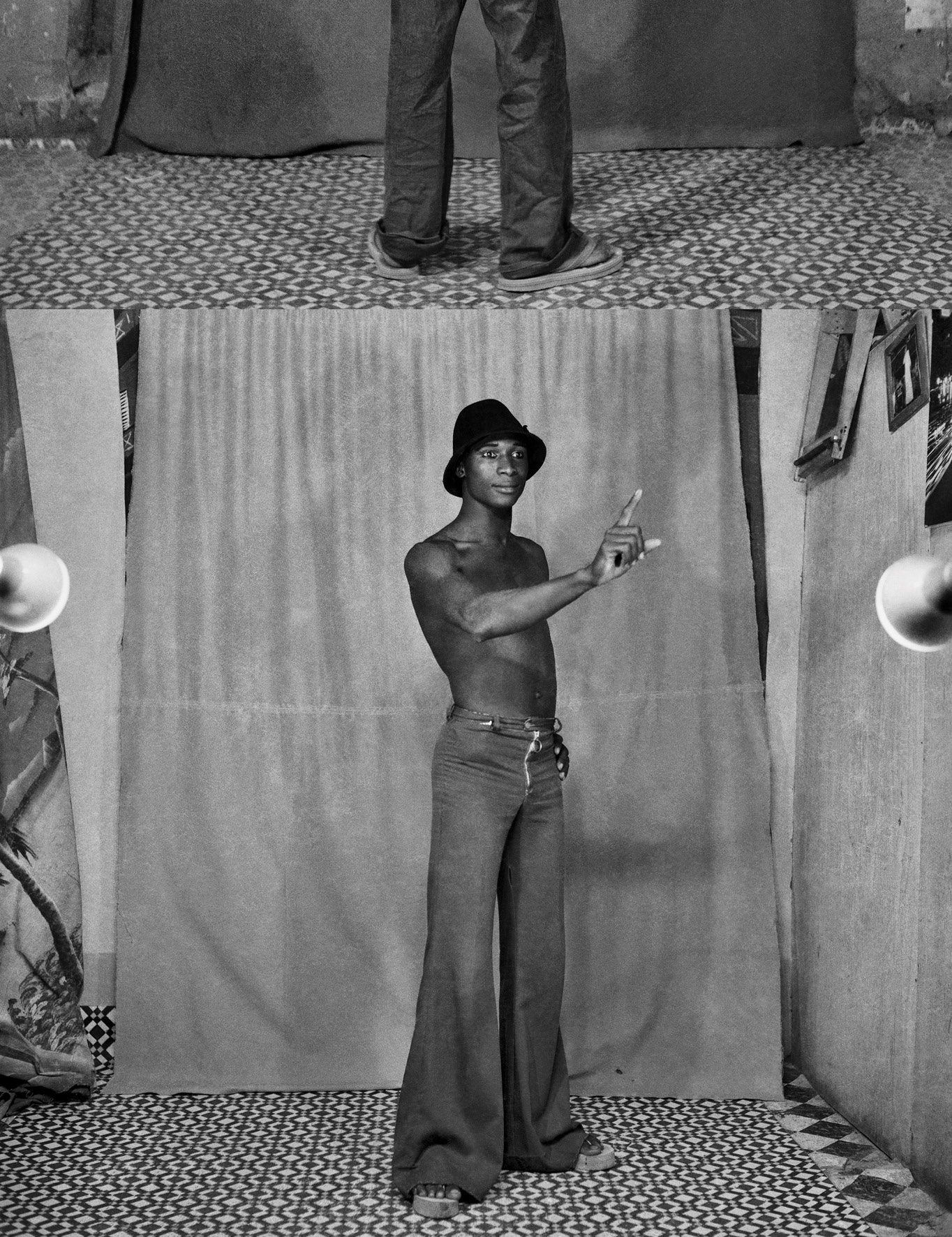

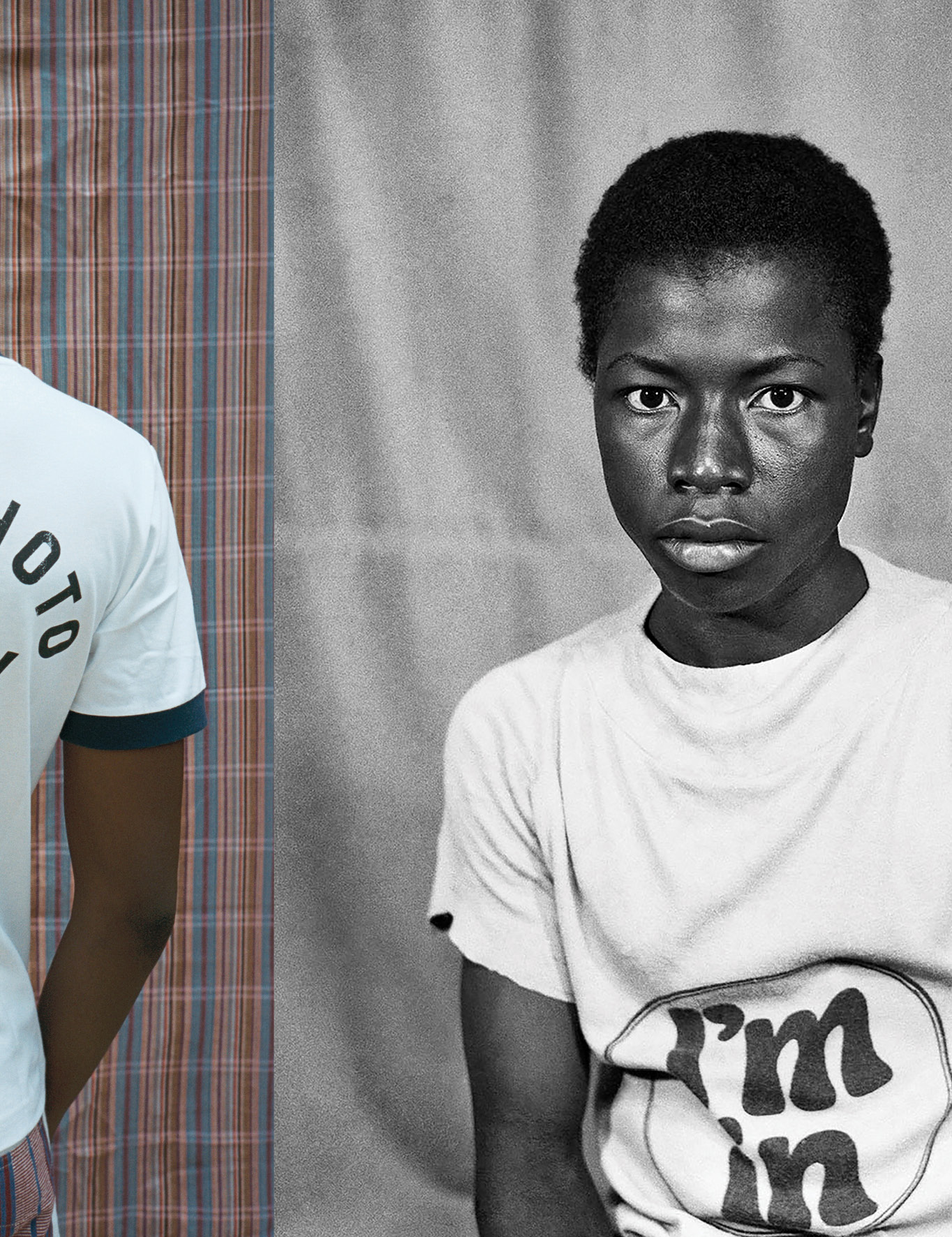

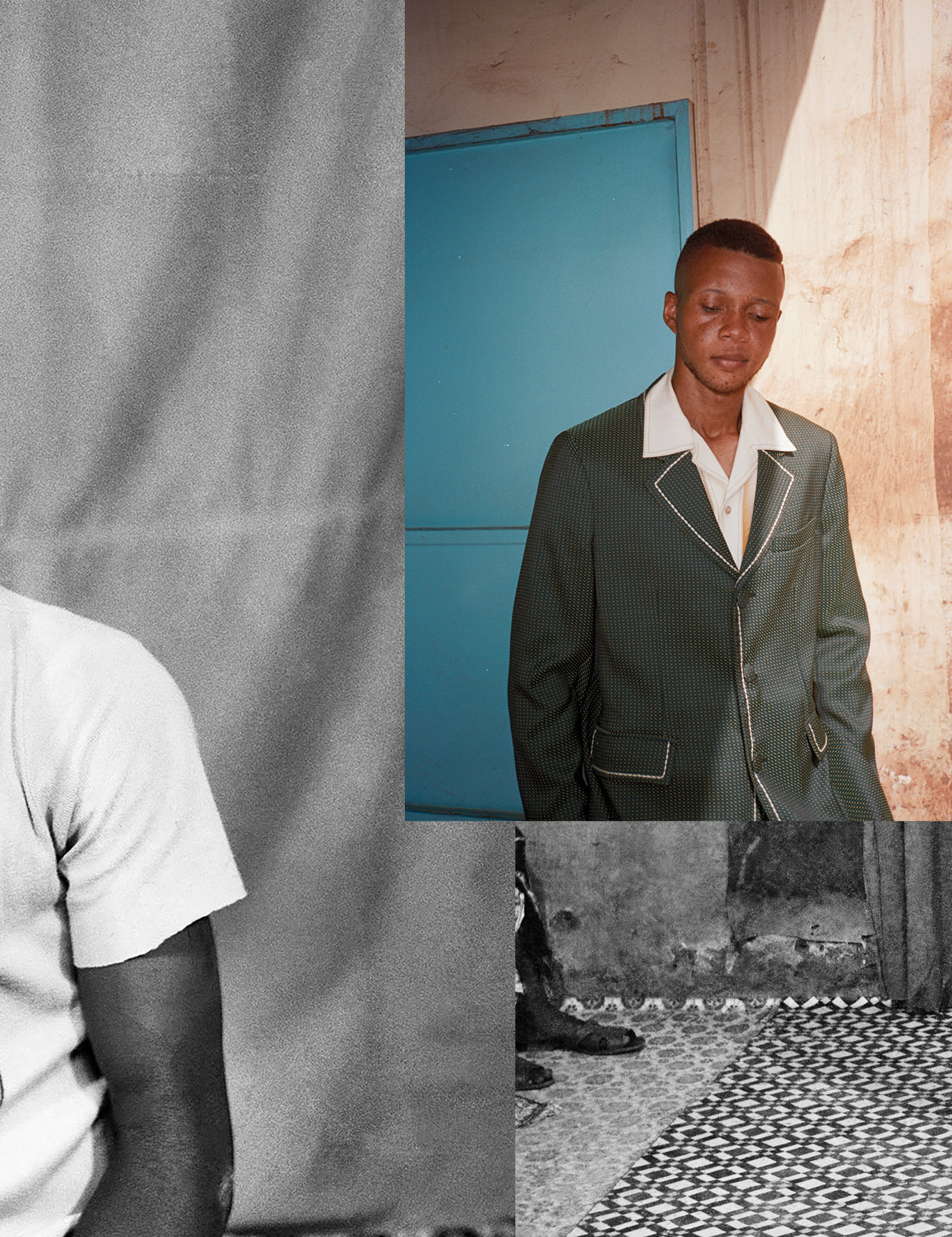

For her SS22 presentation Volta Jazz, Grace turned to the Bobo-Yéyé music and culture of post-revolutionary Bobo-Dioulasso, the largest commercial city in Burkina Faso (formerly Upper Volta), of the 60s and 70s. More specifically, the band Volta Jazz and the work of Sanlé Sory, the photographer that documented the nocturnal life of their scene. For this collection, Grace imagined a poetic fiction in dialogue with the artistic and cultural freedom of that period; one infused with the rhythms of Volta Jazz and animated by Wales Bonner’s eight years of research and exploration into the art and culture of the Black diaspora.

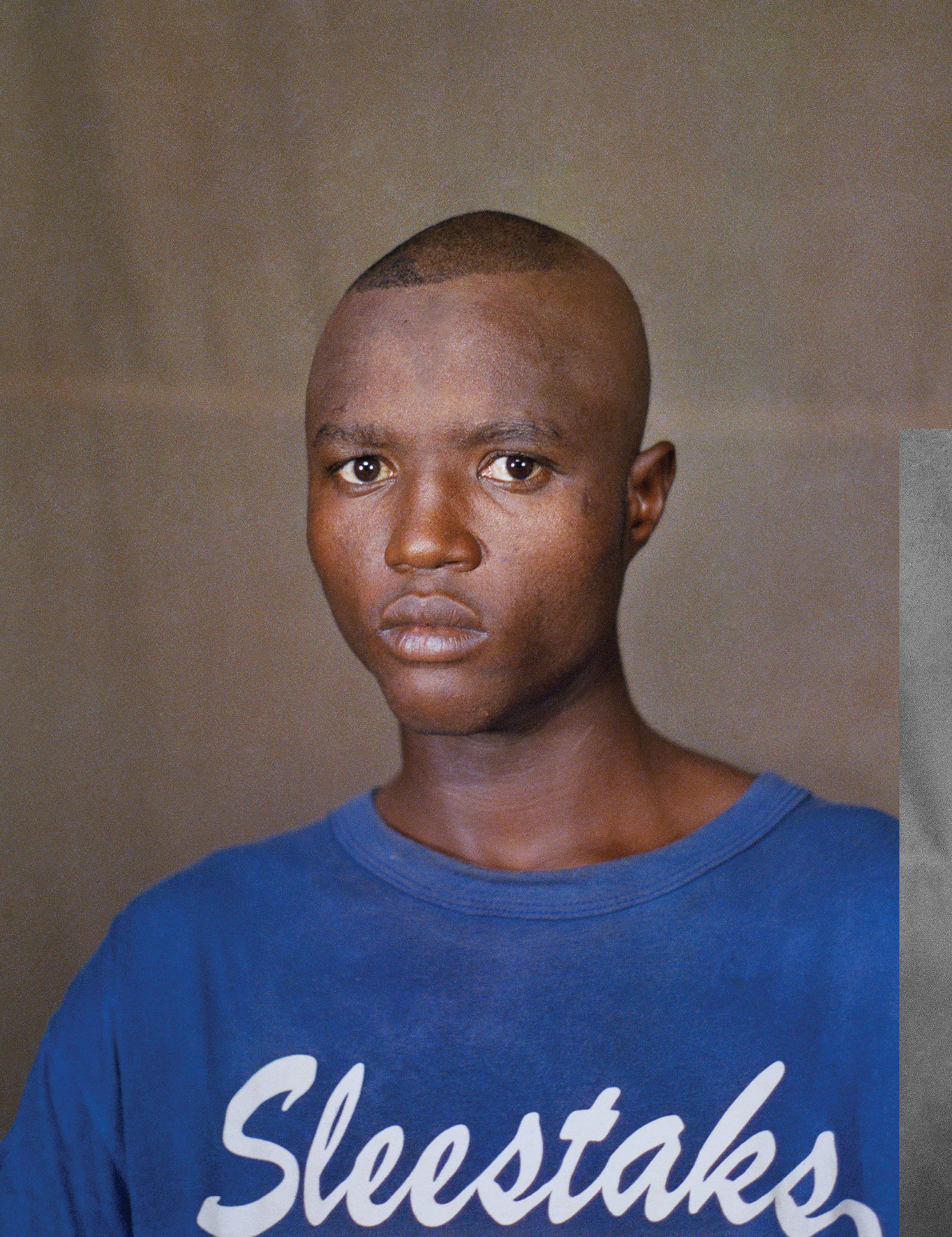

On the occasion of i-D’s publication of a selection of archival photography alongside newly commissioned portraits by Sory of the Wales Bonner SS22 collection, Grace and I sat down to discuss the genesis of her Volta Jazz presentation, collaboration, and the role of sound in her practice.

So I asked a few of our mutual friends what I should ask you about for our conversation today. Everyone had the same response – they wanted to know: what is Grace reading these days?

This year I’ve been really committed to reading the Vedas, and it’s kind of a goal of mine to read all of them. The Upanishads, then the Dhammapada, the Rig Veda. It’s become a sort of daily practice, which is nice. There was also a show up at MoMA recently about post- independence architecture in India, so I got the catalogue for that, and it’s been super inspiring.

Recently I’ve been reading a lot of Etel Adnan, the artist and poet. I’ve often found that what I’m reading ends up creeping into my work, whether I’m writing something or working on a film, even when the two are completely unrelated. Do you find that this happens to you when you’re working? Did it happen at all while working on Volta Jazz?

That collection was guided by music as an entry point. More abstractly, I am always interested in the aesthetics of sound and trying to think about a way of translating what something sounds like into what something feels like, or into a piece of clothing. I’m interested in photographic archives around recording, recording what people look like, what we were wearing around sound. So that’s why I found Volta Jazz’s work interesting, because it becomes a record that articulates the sound of a time, or something that can allow for a translation of that aesthetically.

The photograph holds traces of rhythm, it’s not just a deposit of the visual, and a particular cut or drape can be a trace of the music that was playing when it happened.

Yes. I often use photographic records to give me some understanding of a sound, and this is why someone like Terry Adkins is so inspiring to me, because there’s a lot of potential in what’s created, and it gives off a feeling of sound. I think I’m always interested in artists that have a sense of magical potential around what they’re creating. So I think it was just revolving around ways of perceiving style and beauty through photographic archives – thinking about style that emerges in a more unselfconscious place. Also just reflecting on the images that are part of my subconscious or that have built my understanding of style.

I admire the immediacy of this collection. It’s as if we’ve been through the research with you over the years, and now we can read all of the places you’ve taken us to in your work now even when it’s quite specific.

I was working on this collection last year and I think I felt a bit freer. I felt that what I’ve done up to this point has allowed me the possibility to be free and to be playful, to feel that I didn’t need to do things in the same way as what I’ve done before. What I’ve done has already demonstrated a way of thinking, so there’s a lot more potential and space to move forward in a different way. My thinking is more future-oriented at this moment, I would say.

What you’re saying makes me think about how, with certain film directors, every single movie, even when it’s a different story, seems to happen as a part of the same fictitious world, even when these characters don’t migrate horizontally between films. I think about Wales Bonner in that way. For those of us who have followed the brand and its stories and branches of research, I feel more and more a part of the world. I started to register how an engagement with Volta Jazz feels continuous with an engagement in Lovers Rock, which feels tied to your research into Ben Okri and Ishmael Reed. With Volta Jazz, did you encounter the music or photography first?

The photography, I think. I was aware of Sory’s work documenting fashion and style first, and then I became friends with someone who has worked closely with him and is also a big music collector, a collector of records. Sory’s cousin was a founder of Volta Jazz, and so Sory naturally came to document the music and the nightlife. I came to know the photographs, but then I also came to know the connection between the photographs and sound. I think I’m also really interested in archiving practices, and working with archival music – this idea of building an archive or building a library or an institution. It just kind of collided with certain interests that I have.

My writing sort of behaves as archival notes for what I’m reading, and I’ve only recently started to accept the idea that the value of what I’m writing may be in the act of placing things near to one another, in the disparateness of the reading which generates an archive or a bookshelf of sorts. Writing is a way of organising wide-ranging research and pushing things closer together that might otherwise be held far apart.

I completely relate to that. I think I did start to recognise early on that creating clothing or imagery can communicate something quite deep or complex in an immediate way that people can feel. It’s a very direct and accessible way of communicating; it’s not impenetrable. It’s interesting how powerful it can be to put something in context by communicating through clothing.

Is nostalgia important for you?

I wouldn’t say I’m nostalgic. But I do think I see things in fragments of memories, or text, or images. I think that I’m piecing together fragments of memories of the world and that there’s a lot of fluidity or spaciousness to them.

In the new Sory images shown here, one of the things I was surprised about was that it’s not nostalgic at all. It’s completely contemporary. He doesn’t go back and try to reconstruct the style of photography or the context. It’s shot in colour. I found it made the garments feel deeply contemporary. They say something about now. What was it like to collaborate on these?

Through collaborating with different people, the moment you start having conversations, that’s what I find quite exciting. I might be interested in something in a collaborator’s work, but then by talking to them, they can present a much more expansive world and many more possibilities, which then opens me up to looking at it in different ways. For example, I’m thinking of Ben Okri, because I was thinking about The Famished Road and this character, the spirit child, Azaro, and a moment when he’s moving through the market. That was really something I was really interested in for a whole collection. But then, speaking to him, he’s moved on so much from writing that, and he’s thinking about completely different things now.

Once you start the conversation, digression is inevitable, isn’t it

Conversation makes the work very expansive, and I think that’s been important to me to be in dialogue and really not have a singular way of looking at something, and have space for a multiplicity of perspectives. It challenges any preconceptions that I might have and really inspires me. In that sense, I like to get out of my depth and be in dialogue with people whose work I really admire. It makes me feel I need to do better work myself.

So it’s super exciting that Sory was open to working on this. And we’ve been really lucky that we’ve been able to spend a lot of time in Sory’s archive. There’s a lot of unpublished material, and here there are works that haven’t been seen before. Sory has been super hands-on and excited about working on this project, responding to imagery and ideas; it’s amazing, I think he’s 79 years old now. What’s been so interesting about this collaboration is that we’ve asked him to respond to how he sees Wales Bonner characters in his world. He’s been responding to the kinds of casting and characters that are a part of Wales Bonner’s language, which have in turn been inspired by his work. He’s showing where the connection lies between the two worlds, so I think that’s quite interesting, that dialogue or that kind of reflection or mirroring based on a certain common ground or commonality.

It creates its own world, right? Now Sory feels so much a part of the same world as other people that you were engaging with years ago. And they form their cosmos.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.

Credits

Photography Sanlé Sory

Models Issouf, Fadil, Fayçal, Cheick, Yacine and Ayouba

Production and art direction Esther Hien

Special thanks Sanlé Sory, Clément Hien and Florent Mazzoleni

All clothing Wales Bonner, trainers Wales Bonner x Adidas originals

Archive images Sanlé Sory / Volta Photo (Bobo-Dioulasso), courtesy of Tezeta (Bordeaux)

1 ‘Regardez Moi Attentivement’, 1980 2 ‘La Relève’, 1982

3 ‘Je Suis dans le Coup’, 1980

4 ‘La Timidité’, 1971

5 ‘Jeunesse Djombolai’, 2002

6 ‘Homeboy Bobo’, 2004

7 ‘Impavide Fan de Bruce Lee’, 1974