In the 80s and 90s, English photographer Janette Beckman lived in the East Village on Avenue B and hung out at Jem’s; she explored the outer boroughs and shot multiple concerts a week for the British press. Janette took portraits of the movers and shakers of the nascent hip-hop movement—which, for her, resonated with the punk movement she’d captured in her native England in the 70s: both were scrappy marginalized communities of hustlers who turned a sense of futility into unparalleled creativity.

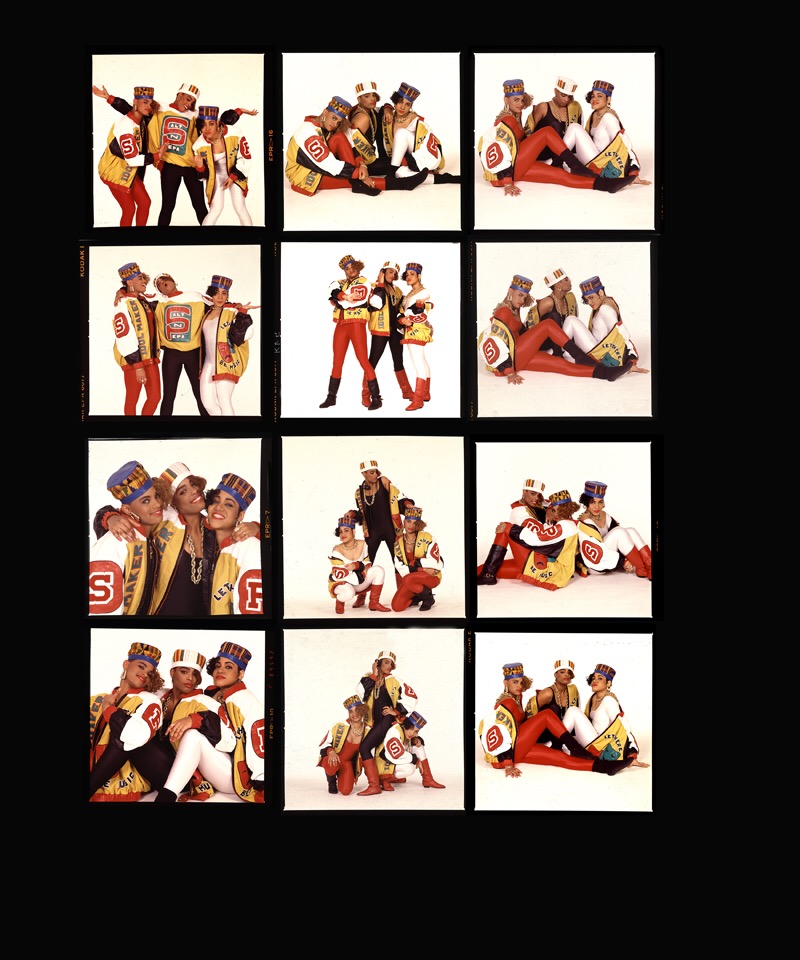

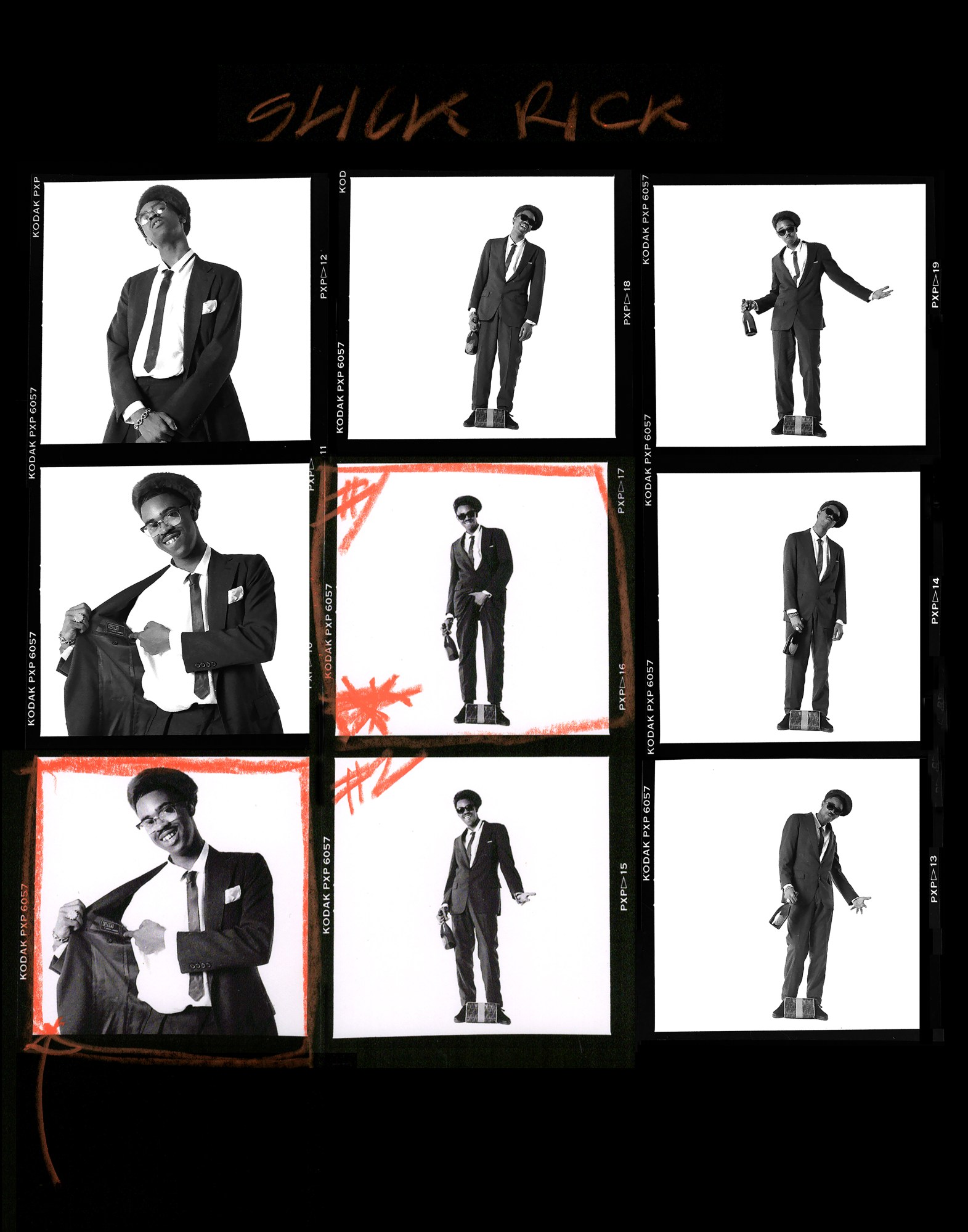

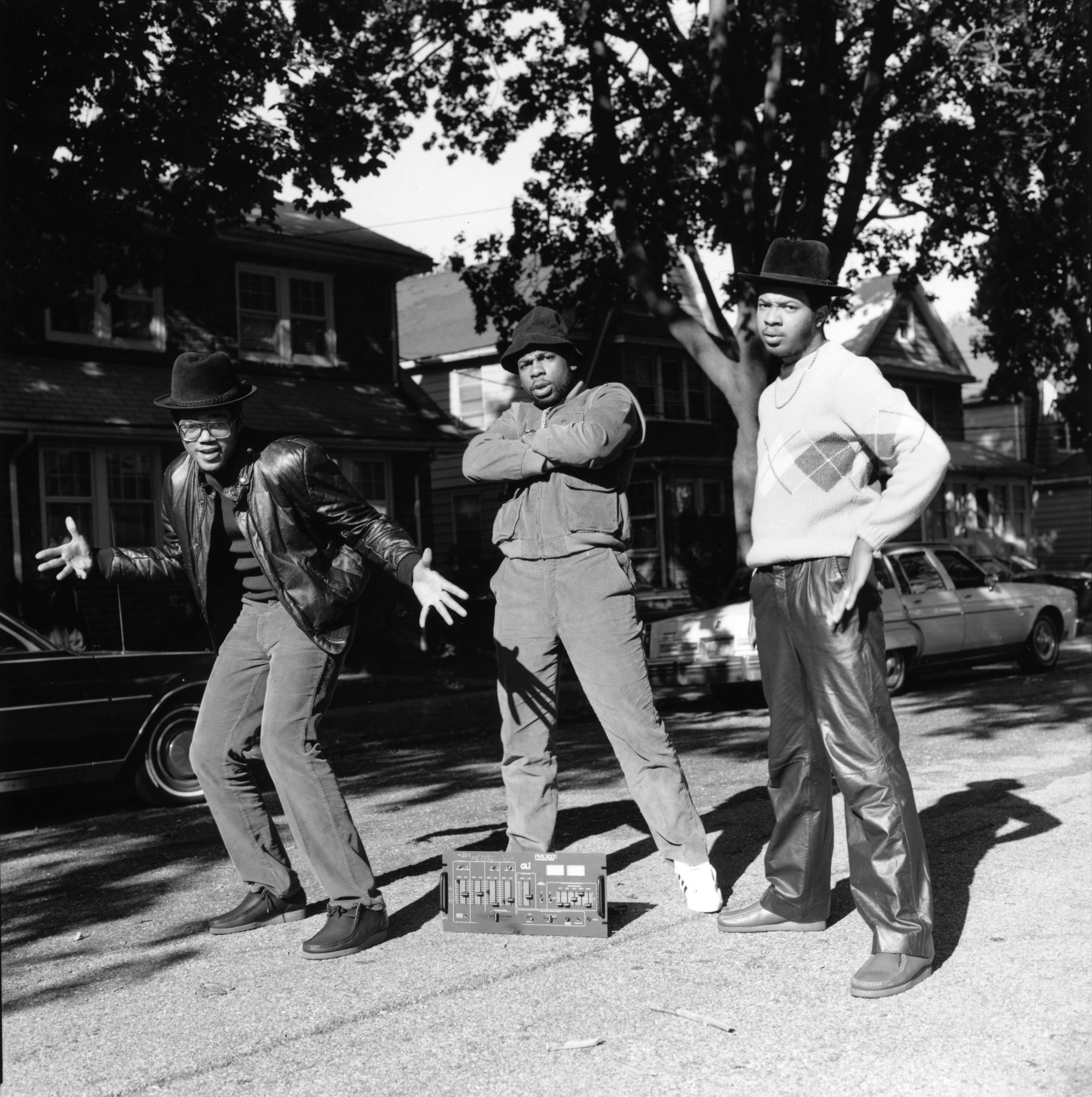

Beckman was one of the 60 photographers—and, moreover, one of the very few female photographers amongst those—featured in Contact High: A Visual History Of Hip-Hop, an empowered exhibition at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles, which concluded last week. The show—curated by Vikki Tobak, with creative direction by Fab 5 Freddy—traced hip-hop visually, through editorials, magazine covers, as well as that telling raw material: the contact sheet. The sounds of Notorious B.I.G. and Aaliyah and Dr. Dre changed music but so too did their signature styles, their particular silhouettes, their gazes. Beckman’s magnetic images of Salt-N-Pepa—red lips, gold chains, bright lycra and oversized leather—and elegant black-and-white portraits of the likes of Queen Latifah, Gang Starr, and Big Daddy Kane are iconic for their candor. They feel a breath of fresh air relative to the hyper-stylization that has become the celebrity image norm. Speaking from her Bond Street studio, Beckman discussed the frustrations of image control, maintaining authenticity, and the magic that occurred at a Mexican restaurant in 1988 when a group of female rappers gathered together.

How did you decide to become a photographer?

I grew up in London and went to arts school; I studied photography. When I came out, in the late 70s, early 80s, punk was just starting to happen. One day I walked into a music weekly with a portfolio—I didn’t have any music pictures in it whatsoever. I met this woman Vivian Goldman; she’s a pretty famous writer now. She said: ‘What are you doing tonight? Do you want to photograph Siouxsie and the Banshees?’ So off I went. I’d never photographed live—I’d never photographed a musician before! I went running back to my darkroom in the middle of the night, developed the film, printed the pictures, and went in the next day. She was like: ‘Oh these are great!’ and gave me another assignment.

I went on to work for Melody Maker, another weekly music paper. …I was getting all the new things that nobody really knew anything about back in the day. I got to photograph punk bands and soul music and Boy George and I went to Italy to photograph The Clash. I was shooting two or three bands a week. Then I started to work for The Face. At the time it came out, it was really revolutionary, because it was about the kids as well as the bands. I had a picture, a full-page spread, of these guys called the Islington Twins in the first issue—I photographed them when I was teaching photography and darkroom techniques part-time in a school at the Kingsway Princeton College, where a lot of squatters and punks were going. Johnny Rotten had just left—of course he was John Lydon at that point.

How did you transition from photographing British punk to American hip-hop?

When the first-ever hip hop band came to the UK on a tour, I put up my hand in a meeting to photograph them. I went to the hotel where they were staying. In the lobby, I was just like: ‘You look interesting! Can I take your picture?’ It turned out I photographed some of the most important people in hip-hop culture: Futura, Rammellzee, Afrika Bambaataa , Grandmixer DST , Fab Five Freddy. I went to the concert that night and all those people were onstage together. I’d never seen anything like it. A few months later, I was coming to visit a friend in New York, on East 4th Street, and ended up staying.

How familiar were you with the music of the musicians you were shooting? Was familiarity with the sound an important component of being able to get a memorable portrait?

It’s really important, to this day. Making a portrait of a person—any information you can get is very helpful. Usually, back in the day, doing a portrait would go along with going to a concert or hanging out, so I always knew what the music was. When I was on tour, I saw the concerts and would hang around backstage. Sometimes I would have to wait for three days before I could get my picture, because obviously a photographer from some music magazine is low on the rung of what’s going on.

We didn’t know [hip-hop] was going to be so important. You’re just in it, you’re involved in it—you’re going to concerts anyway. And the British press was obsessed.

It’s starkly different today, in terms of how a musician or group manages his/her image. It seems like there was authentic access when you were shooting, whereas everything now is so carefully curated and polished. How did you experience this shift?

Back in the punk days, and the ‘80s-era hip-hop days, those cultures grew out of what we’d call in England the working-class. They didn’t see a future—there were no jobs. New York was broke when I arrived here; London was broke when I left it. People didn’t have money: they didn’t have stylists, they didn’t have hair or makeup people; the managers were just managing the bands, they didn’t try to tell the bands how they should look. Around the early ‘90s, suddenly, things in the hip-hop world were changing. PR people had ideas about what access you were or weren’t allowed to have. I just shot at the Newport Jazz Festival, and you were only allowed to shoot the first song for every band that was playing, which is insane. Bands look great during the last song, when everyone’s sweaty and they’re really in it! As for flipping through a magazine… you get someone like Beyoncé, who’s already incredibly beautiful, you know she controls every single image that goes out. Before the shoot itself, you’d have to sign a contract saying you won’t release anything that hasn’t been approved. And then there’s Photoshop and everyone looks absolutely perfect. To me, the industry has lost a lot of its authenticity. It doesn’t really tell a story. ’Stories’ are controlled by the bands.

When did you notice this phenomenon really take its toll?

When I first came to New York in 1983, I had two Police album covers under my belt, and numerous pictures of the Clash, Boy George, the Sex Pistols, you name it. I went around the record companies with my portfolio, thinking ‘I’m bound to get some record covers.’ Even in 1983 they were saying to me: ‘Your work is too gritty. You can see people’s spots. We airbrush everything.’ In the end, the first album cover I got was for this band the Fearless Four, a new hip-hop band. They were wearing these bright leather suits, their hair was all jeri curled. It was great for me, but it was ‘we’ll give you this because your stuff is not really what we’re looking for.’

How do you circumnavigate such hyper-conscious attitudes?

Luckily for me, a lot of people still really like authenticity. This year, I shot for Dior in London. Maria Grazia wanted me to shoot the models outside on the street in Kentish Town looking like a punk band even in these couture clothes. We had to find the perfect walls—just as I was always looking for the perfect walls in the punk days to put a band against! I was working with creative director Fabien Baron to shoot products… which I don’t really do. I was a little apprehensive. We were shooting outside and he was like: ‘No, Janette—I want you to shoot them more punk style, like you would!’ And I was like ‘Oh! Now I know what to do!’ I worked with Gucci and Dapper Dan, and I did the worldwide campaign for Levis last year. That was because the creative director told me he loves all my old stuff. We shot everything in the street, we threw a block party. We were shooting DJs and Double Dutch girls, and doing street casting.

What a curveball that brands provide a creatively liberal alternative, more than press!

Just because of my history, basically! People who want to work with me tend to let me do what I do. My job seems to be, a lot of the time, taking the ‘model’ out of models—something that’s very high-end fashion, and taking it back to the street. People are supposed to look like themselves. I really like shooting on location—you get a sense of history. Most of the places I shot back in the day don’t exist. Delis aren’t the same. The cars are different. It gives a sense of place and time.

Otherwise, I find things: I shot rodeo riders in Omaha, Nebraska; an illegal girl fight In Brownsville; illegal dirt bike riders in Harlem; people at the Indy 500 at Nascar in Indiana; a big EDM festival. I did a pop-up portrait studio with, like, a sheet for ‘I Vote Because ’ in swing states. There are definitely people doing things out of the box, and I’m always looking for that.

Did gender ever play into what you could or couldn’t access?

It sounds nuts—I don’t have bad stories. When I came here as a British young woman, I would go out to the Bronx to shoot and they were like: ‘You ain’t from here!’ and I’d go: ‘No, I’m from London!’ People didn’t have money and they hadn’t traveled to Europe. My accent was a conversation starter, and they would feel relaxed. I wasn’t your white American male—I was somebody from another country and they were wondering why I was even interested in what they were doing. It was incredibly helpful.

Can you talk about the “Women Rappers NYC” shoot? Despite powerful exceptions, rap is still a pretty masculine realm—but this was from 1988! It seems radical. What was that shoot like?

I shot that for Paper Magazine, which was a start-up by friends of mine, Kim Hastreiter and David Hershkovits. It started as a broadsheet that folded over. We all worked for free. They knew that I was photographing a lot of hip-hop at the time: that’s when Salt-N-Pepa and MC Lyte and these female rappers were coming up. They were talking back to the boys. It was very exciting. We decided to have this shoot with just the ladies. This was actually in a Mexican restaurant on West Broadway that no longer exists, but it had this weird little stage thing—I didn’t find the location. All the women turned up with their boyfriends, and the editors were like ‘Actually, no men are allowed in here, so all you guys are gonna have to find something to do for a couple of hours.’ I thought that was brilliant. So the boys went off, and we got all the women onstage. They all knew each other because it was a small community. They got Millie Jackson in there—she’s kind of like the godmother of women in hip-hop. Everyone turned up in their best—a lot of these women are wearing Dapper Dan. I didn’t know who he was at the time! They look strong, happy to be around each other. It was a roundtable discussion and I really wish I still had that issue to know what they were talking about. These are the legends.