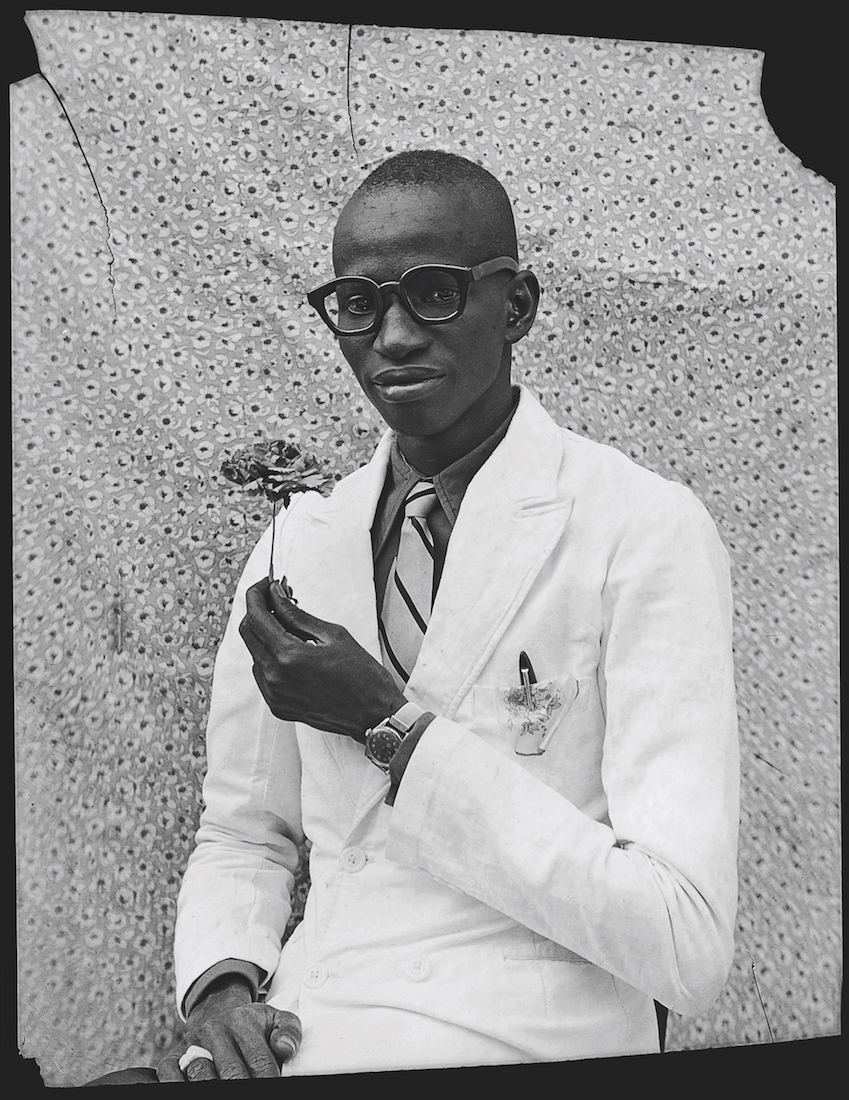

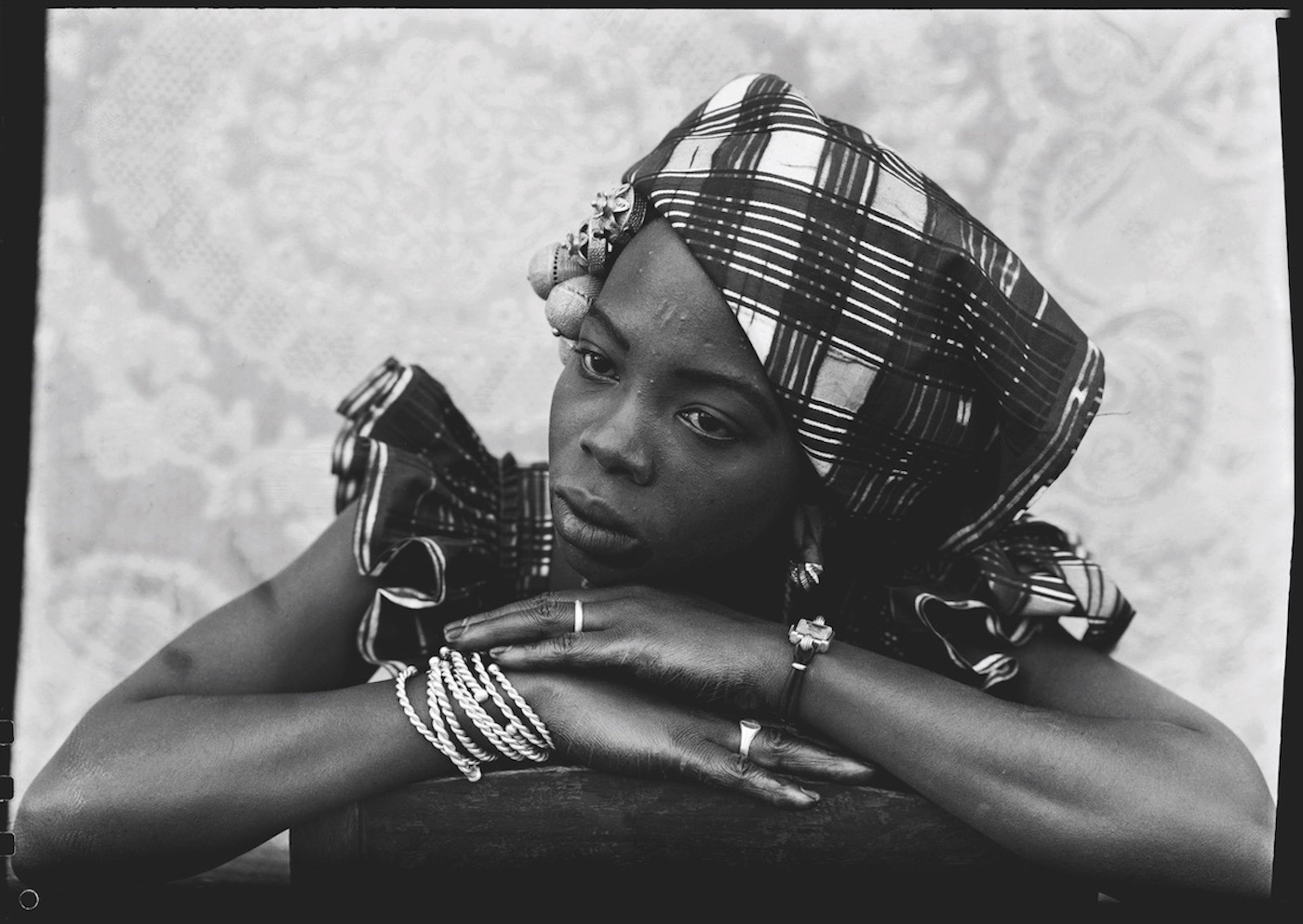

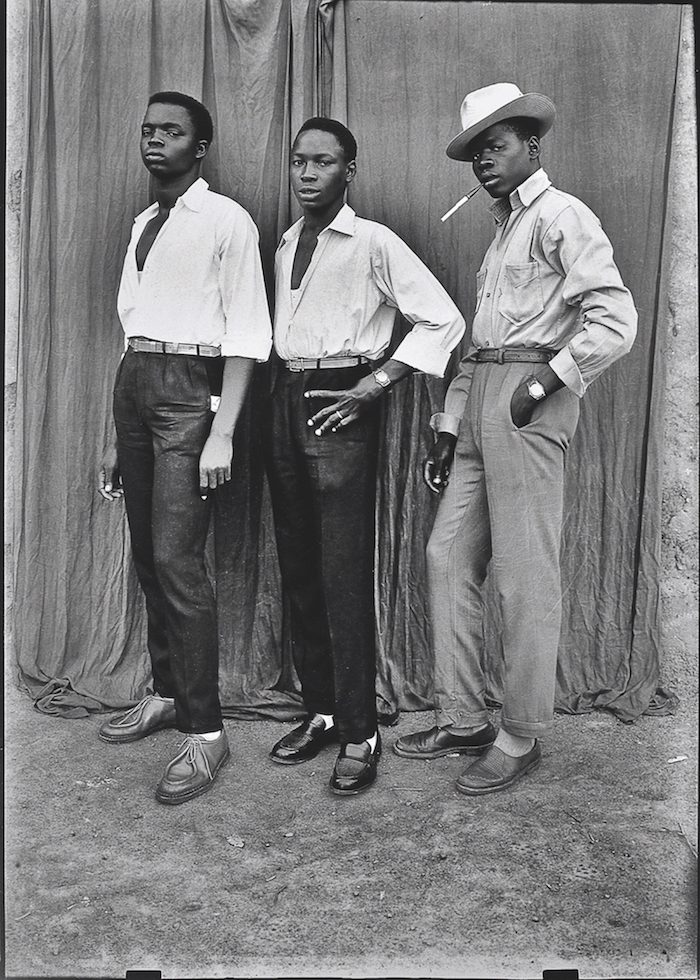

The vibrancy of the fabrics, the painstaking folds of the clothes, the deeply solemn expressions: these are the signatures of Malian photographer Seydou Keïta‘s striking black-and-white images, which feature mid-20th-century youth in his native Bamako. A new eponymous exhibition, opening today at the Grand Palais in Paris, is the broadest retrospective of the photographer’s work to date, bringing together almost 300 photographs.

Keïta was born around 1921 in Bamako, then the capital of French Sudan. An uneducated carpenter’s apprentice, he received his first box camera, a Kodak Brownie, from his uncle, during his childhood. By 1939, he was making a living as a photographer, and in 1948 he opened a studio on his family’s land, attracting travelers from West Africa as well as a local youthful clientele.

Keïta specialized in black-and-white portraits, featuring individuals but also couples and groupings of friends, siblings, and young families. Always relying on natural light, he mostly shot subjects at a three-quarter view or standing against patterned backdrops, which he would hang in front of a dirt wall in his courtyard, changing them out only when they got grubby. (When Westerners began clamoring for his images decades later, Keïta was able to date his work, roughly, by tracing the succession of the fabric backdrops.) With the money he earned, he acquired Western-style clothing, a radio, jewelry, a car, and a scooter, which he made available to clients so they could integrate exotic accessories into their pictures. Keïta rarely knew the names of his sitters, but what these anonymous subjects emanate is incredibly powerful and graceful: the men are dapper and polished, the women elegant and expressive.

In the fall of 1960, the Sudanese Republic declared independence and established a socialist regime; in 1962, Keïta closed his studio to become the official government photographer. He retired from photography altogether in 1977 and devoted himself to his hobby, fixing cars.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that Keïta was “discovered” in the West (though the story of how is not addressed in this exhibition). The attention was instant and widespread: he was celebrated globally and exhibited at the Ginza Shiseido Art Space in Tokyo, the Helsingin Taidehalli Helsingfors Konsthall in Helsinki, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and Paris’ Fondation Cartier in 1994. (Keïta had never left his country before any of this.)

Many of the images on display at the current Grand Palais show are silver gelatin prints, from original negatives, that were made during the 1990s for shows of his work abroad. Keïta didn’t keep any original images from his studio after it closed in the 1970s, though some were found in the studio of his framer. The exhibition’s curator, Yves Aupetitallot, notes: “What we’re showing in this exhibition — from 1949 to1962 — is in fact a very small part of his output.” The remainder is at large or destroyed.

Today, Seydou Keïta is compared to other celebrated portraitists such as Richard Avedon or August Sander. His work unquestionably merits this comparison — his images are as beautifully composed, sociologically telling, and aesthetically enticing. Yet, you’re reminded, as you walk through the exhibition, of Europe’s longstanding tendency to omit African art, and of the necessity of a shift towards a culturally comprehensive approach within today’s museums.

Aupetitallot admits that post-colonial studies in France are notoriously “a little bit behind.” “We have a history that is intimately linked to our former colonies. We have woven very strong links, and we have to recognize them and study them,” he continues.

The Grand Palais exhibition “is significant because it’s a look at France’s colonial past, and it’s a prise de conscience that part of African culture has been touched by France — and inversely,” Aupetitallot says. “It’s a culture that has built itself around its contact with the French: unfortunately, around the colonizer. The African kerchiefs have French names: à la De Gaulle, à la Marie Claire, à la Versailles. But we [the French], too, owe elements of our culture to Africa.”

Facing this head-on is a key function — and power — of culture. Aupetitallot says: “In moments of extremely strong tension, like today, it’s about remembering this hybridization. Each [culture] keeps their identity, but also enriches their identity through their contact with the other.”

‘Seydou Keïta’ is on view at the Grand Palais in Paris through July 11, 2016.

grandpalais.fr

Credits

Text Sarah Moroz

Photography Seydou Keïta, courtesy Grand Palais