Coming of age in Harlem during the 1940s and 50s, photographer Shawn W. Walker was a quintessential New York City kid who learned to move fluidly between different worlds from a young age. Shawn’s parents moved north during the Great Migration to create a better life for themselves, making a home for their two boys on 117th Street.

“I didn’t realise we were middle class until I was in my late 20s or early 30s,” Shawn says. His father had a union job with Jersey Central Railroad while his mother was a domestic worker at a white beauty salon. “I was naïve and believed the hype that if you lived in a Black neighbourhood, you were poor. My brother was 18 months older than me, and we were really social kids. We went to dances, and my mother was invited as a guest to parties thrown by the Italians she worked for. My mother was very personable and people liked her”.

Shawn’s uncle also had the touch. By day he worked at Eastman Kodak and on Friday and Saturday nights, he hit the bars of Harlem to sell Polaroid portraits. Polaroids proved to be the perfect solution for folks who didn’t own a camera, nor the time and money to visit a photo studio before a night out on the town. “He started in the late 40s at a time when people don’t have many photographs, particularly Black folks,” says Shawn, who used to accompany his uncle, carrying the film and cameras. “You could get the picture and take it home with you — instant memories.”

Watching his uncle work, Shawn began to see the ways in which photography provided a way to move through the world, connect with people, and express his own point of view; and from his mother, Shawn mastered the ability to move with elegance and grace in whatever environment he found himself.

“I understood photography would take me places that I would have never gone,” he says. “When I started, I really flew with my camera.” He set up a makeshift darkroom at home using an old enlarger his uncle gave him. “My family never figured out what I was trying to do. My mother would say, ‘Why don’t you photography the Ebony [magazine] type Negroes?’ because I was focused on photographing people on the street.”

As a teenager, street life held a certain allure, but as he became more exposed to its dangers, Shawn realised it was not for him. By the late 50s, heroin was on the rise, as it flooded the streets of Harlem through the notorious international crime syndicate known as the French Connection, setting the stage for the rise of local kingpins like Pee Wee Kirkland, Frank Lucas, Nicky Barnes and Frank Matthews, aka Black Caesar, whose legendary exploits fuelled the Blaxploitation era of the 70s.

But life on the streets was brutal, as Shawn witnessed his closest friends fall victim to addiction, ending up strung out, dead or incarcerated. “I had a feeling there was something meant for me in life and that kept me straight,” he says. “I never shot any drugs. I didn’t need to be unconscious or oblivious to what was going on around me. A buddy told me about a group of photographers, and that’s what saved my life.”

In the fall of 1963, two groups of local photographers came together in Harlem to discuss the under-representation of Black photographers in the art world — only to seize the moment to create the Kamoinge Workshop, which has since become the world’s longest-running photography collective. Comprised of professional photographers Roy DeCarava, Adger Cowans, Louis H. Draper and Ray Frances, and emerging photographers like Shawn, Herb Randall and Anthony Barboza, Kamoinge took its name from the Kikiuyu people of Kenya — meaning “a group of people acting together”. The Kikiuyu had mounted a 75-year resistance movement against British colonisers, helping Kenya finally achieve independence that same year.

It was an auspicious sign for the newly formed photography group, which adopted the same liberation-led, collectivist approach. Every Sunday, Kamoinge members gathered in one of their homes for a day of critique, conversation and community.

They held rousing discussions of art, culture, music, film, painting and politics, the elders offering the benefit of their insight and experiences for newer artists like Shawn, who recognised these encounters as “my Sorbonne”. Members discussed inspirations, looking to the work of painters like Rembrandt, filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman and photographers like Minor White, Irving Penn, and Moneta Sleet Jr. — providing Shawn with an ample arts education.

“I love that we are timekeepers; we can capture time and take it away with us. That’s as profound as it gets,” Shawn, who views his practice as a street documentarian and cultural anthropologist, says. Working two or three jobs to support himself, Shawn was determined to succeed as a photographer at a time when very few Black artists could make a living in the field. Whether shooting for the Harlem Daily newspaper or on the set of the groundbreaking PBS television show Black Journal, Shawn always put his vision first, creating a singular archive of contemporary Black life.

Over the past 60 years, Shawn has gone on to create over 100,000 images that were collectively acquired by the Library of Congress in 2019. As the first Black photography archive acquired by the 223-year-old institution, Shawn’s work stands beside his contemporaries like Toni Morrison, Thelonious Monk, Maya Angelou and David Dinkins, the first Black mayor of New York.

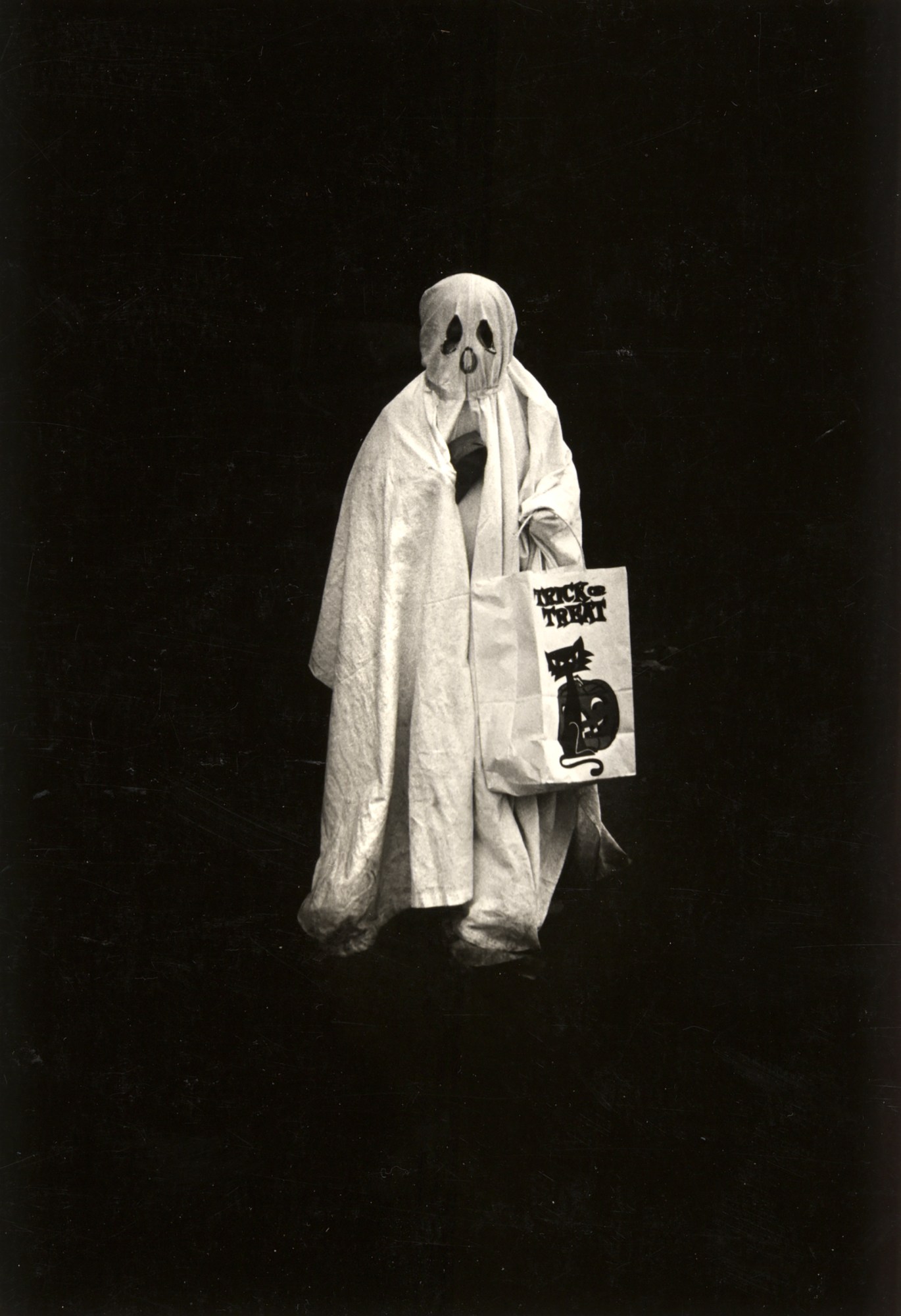

Shawn recently rediscovered a wealth of early exhibition prints that had been safely stored (and forgotten) in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture archives for over a half-century. Brought together for the recent show, Lost & Found at Bruce Silverstein in New York, the works offer a revealing look at Shawn’s first forays into photography on the streets of his hometown.

Featuring scenes of children playing on the streets and in empty lots, and proudly waving the American flag at local parades, Shawn’s photographs offer a delicate balance of innocence and loss, especially as heroin begins to impact the community. In 1970, Shawn photographed the people he was hanging out with at the time, sharing their challenges to survive in a feature story published by Essence magazine.

“I have not seen these pictures in over 50 years,” Shawn says of the rediscovered prints that he made in his youth. “I felt this early. I was given a talent. Yes, I studied and trained hard, but I had something that I was given. Fortunately, I was able to teach and that kept me in the field and paid my bills so that I didn’t have to stop what I was. But I still had people say, ‘Well, when are you going to get a real job?”.

Credits

All imagery courtesy Shawn Walker