This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Earthrise Issue, no. 368, Summer 2022. Order your copy here.

“We’re trying to run this in a totally contradictory way to how traditional capitalism, or American capitalism works,” says the American artist Dan Colen. He is talking about Sky High Farm Workwear (SHFWW), the new clothing brand that exists to donate part of its profits to Sky High Farm — a nonprofit organisation founded by Dan 10 years ago, committed to supporting food sovereignty today by donating 100% of all produce grown and livestock raised.

The point is this: most fashion brands are set up to make money for their investors. What you buy and what you wear often just drives profit to the already-wealthy. But can it be done differently? Can a new brand look and feel like a new brand, yet act in a totally different way?

SHFWW is workwear with heart: trippy, full-pleasure clothing, the logo a luscious strawberry cuddling up to a sweet crescent moon. There are sweatshirts, workwear pants, T-shirts, and underwear. Everything is cut with an exact easiness. They’re the kind of pieces you want to wear and wear and see yourself still wearing in twenty years time.

Not only do the clothes act as walking advocacy for food justice, but each piece of SHFWW does good work. “Over 50 percent of all profits will always go to food security,” Dan says. “Initially to Sky High Farm, but over time we feel like we’ll be able to generate enough revenue to share with other organisations as well.”

The brand is co-founded by Daphne Seybold, who until recently was a beloved member of the Comme des Garçons and Dover Street Market family in New York. She says that Sky High Farm is the brand’s sole reason for existing. “This pure and undiluted purpose is what makes us unique,” she says, “and – we hope – a compelling model for a new kind of brand, one that is less a fashion company, and more a vehicle for creating accessibility to, and engagement with, the Farm’s work.”

The pieces are manufactured and distributed by Dover Street Market Paris, the emerging brand incubator that also supports labels like ERL, Vaquera and Honey Fucking Dijon. James Gilchrist of DSMNY, says that minimal environmental impact is crucial. “SHFWW works with as many recycled yarns and deadstock materials as possible throughout the collection. The deadstock in particular is extremely varied and encompasses fabrics, vintage garments and inventory from other brands – for example the CDG SHIRT collab that was just released in which SHFWW customised iconic past season CDG SHIRT pieces.”

“Fashion is this amazing vehicle for us to share ideas and to connect with a wider audience about land justice and food justice.” Dan Colen

Dan Colen is the creative director for SHFWW, working with an ever expanding list of collaborators: Balenciaga, Comme des Garçons SHIRT, Converse, and, this upcoming season, a capsule with Tremaine Emory of Denim Tears. “Without community, fashion is meaningless, so it’s everything,” Tremaine says. His knits, long coats and suiting for SHFWW are printed with seed packets for food such as okra, collard greens, black-eyed peas and watermelon. “The pieces are inspired by foods we grow up eating in the African American community,” Tremaine says. “There’s also a deeper meaning in the foods I choose as iconography, but that is for the wearer and viewer to dissect.”

Collaboration is as much part of SHFWW as it is Sky High Farm itself. “SHFWW is not defined by a single person or team,” Daphne says. “It has always been the collaborative sum of many contributors, a community that lends support, resources, passion and energies to the brand’s creative enterprise and advocacy.”

“It’s just infectious,” Dan says. “I see it with every single person we collaborate with. The second we are on a pathway together, they immediately become more and more invested.”

In 2011, Dan never had any intention of starting a farm. “I’d just started making a living doing what I’m doing, and I had a little more money than I needed,” he said. He’d found sudden global fame for his art in the 00s, particularly the installation Nest with his friend Dash Snow, made from torn up phonebooks. Snow died from a heroin overdose in 2009. Dan cleaned up his life and looked upstate to buy land. “I was looking in the mountains, at forests,” he said. “I ended up in an area that was more agricultural land. I realised that to connect to pastureland, I’d have to farm it.”

His art practice was already enough of a business – he didn’t need another. He was talking with a friend who worked in public health, who said, “well there are so many people who have no access to fresh food,” Dan says. “I grew up in New Jersey, and there’s food insecurity everywhere. The idea to bring fresh food to communities in New York City, I immediately felt it really resonated.”

Things moved quickly. Sky High Farm was built in 2012, and the first food produce was donated in 2013. “All the produce and all the meat has always been donated,” he says. From the beginning, the thinking was both specific and diverse. “There are different people with different backgrounds,” he said. “To be able to grow foods that are culturally appropriate for those people was always a big part of the work we were doing. So even before we started farming, even before we started turning the soil, we were already talking with local food pantries [the US name for food banks] about what their clientele was really looking for. We really grow with the communities in mind.”

But it wasn’t just about what to grow, it was about how to exist. For the first few years, Dan funded the farm through his art practice. Sky High Farm did get approval to become a not-for-profit, but acting like a regular charity seemed limiting. “Charity in a lot of ways has its own systemic issues,” Dan says. “And we didn’t want to create a traditional organisation.”

Around the time of the pandemic, Sky High Farm finally became a not-for profit organisation, but with another plan: “having it in a parallel path with this for-profit organisation, with the goal as ultimate impact in food security and land stewardship,” Dan says. “We really wanted to leverage culture, which I think is something traditional philanthropic organisations have a hard time doing. Not only culture but, for lack of a better word, ‘cool’. Fashion is this amazing vehicle for us to share ideas and connect with a wider audience. People want to hear about land justice and want to hear about food justice as they’re consuming their popular culture.”

The ambition of SHFWW is to change the narrative of donating. “The brand is really trying to turn every customer into a donor,” Dan says. “What the brand is trying to do is deconstruct the myths around a donor class, the idea that only wealthy people can be donors, that only they can operate in a philanthropic mode.” Also different is the internal structure of SHFWW. “We’re going to be an employee-owned company,” Dan says, “so everyone who works for us is going to be able to benefit from their hard work.” Most for-profit companies are dedicated to returning money to their investors i.e. rich humans who really don’t need any more money. “What we’re trying to do is structure the brand so that employees who need the money the most get it the quickest. Only in seven or ten years will we be returning money to any investors.”

James Gilchrist gives more detail on the fresh way of working. “We have established a new financial structure,” he says, “in which everyone in the supply chain takes slightly smaller margins, so they can still make a profit but also allows for as much money as possible to be donated back to the farm. The overarching idea is that everyone including the end customer is a donor in that all profits from the brand will go directly to sustaining the farm’s organisational mission of food justice.”

“I think it’s so important for artists to enter spaces they don’t know because they can transform those spaces. Artists think differently.” Dan Colen

The aim here is speed. “We realised there’s no point doing this unless we can leverage the energy and the pace that you can access through the for profit structure” Dan says. “We’re trying to bring not-for-profit ideals to the for-profit world. But the not-for-profit industry is also broken, and these issues around environmental justice and food justice need to be solved immediately.”

As I’m talking with Dan, I realise something feels different. There’s no cynicism, there’s no irony, there’s no snide. Often with the actions of the art world, there’s a sense of, yeah but why are you doing this? With Dan, there’s total transparency. He pauses, and struggles to find words. “This is still hard for me to articulate,” he says. “Just to speak openly, with honesty, are not things that you associate with an artwork. And it’s weird because I think as artists, and as a public, we are told that artworks are about sharing honestly and openly. But somehow, in the actual art world, people don’t know how to deal with that. They want a conceptual framework, they want strategies, they want layers of meaning.”

“I struggled with trying to validate this to myself,” he continues. “Should I be doing this, is it relevant to me, am I the right person for this? And the simplest way through it was that I felt the work was really important. It was powerful, it was meaningful, it was impactful. And the easiest way for me to do it was to see it through the lens of my art practice.”

Dan has become friends with Linda Goode Bryant, an artist who, in the 70s and 80s, ran the New York gallery Just Above Midtown, which gave early exposure to Black artists such as David Hammons and Senga Nengudi. In 2009, she founded Project EATS, with the mission to give everyone the chance to eat, and live, healthily. “Both art and food nourish us,” she wrote in an email to me. “Food nourishes our body and art nourishes our mind and souls. The resourcefulness, imagination, and creativity we need to make works of art are the same things we rely on when we grow food on small farms and make it available to people who need food.”

Here it is again: artists acting with sincerity, not cynicism. “When I started Project EATS in 2009, it became my art.” Linda Goode Bryant now sits on the Grant Committee of Sky High Farm, which gives grants to young BIPOC and queer farmers ready to take on projects of their own. “I’m interested in learning the passion and emotion that fuels the grantees’ vision and desire to grow food,” she wrote. “How they’ve been able to start and pursue their farming goals. Their strategy and what they need to make their farming efforts viable and sustainable.”

And what does she think about SHFWW? “I think it’s a unique way to generate revenue for the farm without selling the food so it can be given away to those in need,” she wrote. “Their clothes are practical and at the same time have a unique style that makes their workwear appealing to farmers and non-farmers alike.” I want to be a farmer! What does Dan wear from SHFWW? I emailed him to check. “I wear pretty much the same thing every day,” he said. “The double-knee blue jeans and recycled cashmere cardigan, with a vintage T – and, of course, the strawberry and moon undies – to be clear that’s the UNDIES, not the boxers.” Excellent clarification. It all just seems so fertile. “As an artist, what’s always been consistent is that I want to be in an unknown space,” he said. “And one of the easiest ways to do that is to make sure I literally don’t know what I’m doing. If I don’t know how to paint, I’ll make a painting. If I know how to paint, then I want to do something else.”

Recently, he’s been interested in work beyond canvas or sculpture. “I’ve been getting much more interested in performance-based work, which is a space in which I’m totally uncomfortable, and so far it feels very consistent with that practice,” he says. SHFWW is created with this energy. “Without knowing it, I’ve been part of creating another kind of organisation,” he said. “That’s very interesting for me, to explore new ways to connect with an audience, to express ourselves and work collaboratively, and to see what my ideas look like in dialogue with other people with other ideas. I hope to see all these things evolve, but I have no vision for where they should go. I’m excited to be in that vast unknown kind of territory where I like to be.”

Disruptive instincts connect all involved. “Disruptive ways of working are at the very core of DSM as a business,” says James Gilchrist. “It is how powerful ideas and new models such as SHFWW are generated, and a constant challenge for the team. The good energy that this creates is immeasurable and drives innovation. And at the end of the day we need to innovate or die.” Daphne agrees. “Nothing groundbreaking can be accomplished if we simply proceed with the status quo,” she says.

This disruptiveness then nourishes Dan’s own art. “I do think Sky High Farm is unique because it was created by an artist,” he said, “because it was created by someone who knew nothing about structure. I think it’s so important for artists to enter spaces they don’t know because they can transform those spaces. Artists do think differently and I’m really glad that I embraced that natural progression because there were several years where I was like, what am I doing? I feel very grateful that somehow, beyond my best intentions, this is where I ended up.”

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.

Credits

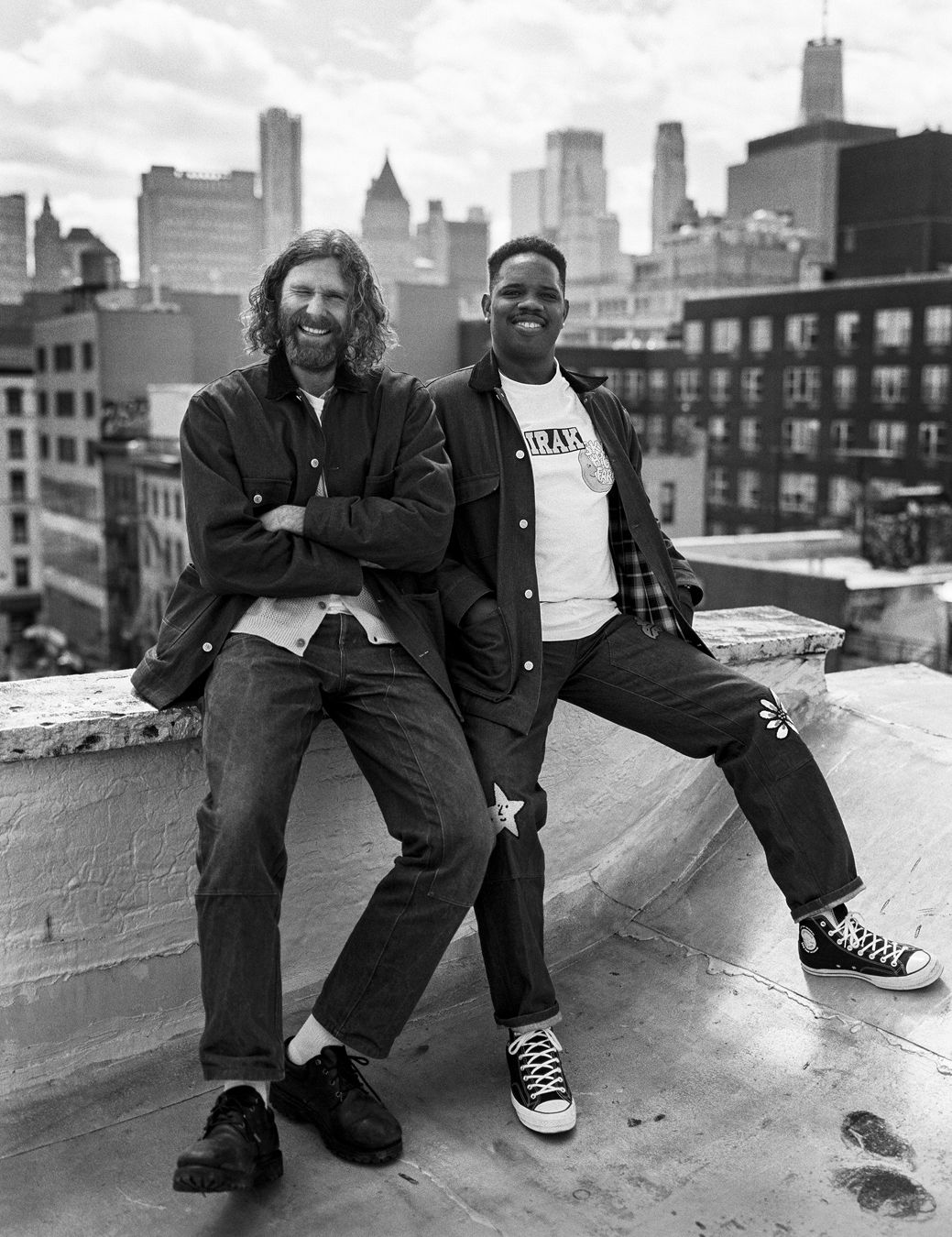

Photography Jiro Konami

Fashion Mac Huelster

Hair Nero using Nakano

Grooming Nanase Ito

Hair assistance Ubu Nagase

Production Camera Club

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING

Casting assistance Alexandra Antonova

Models Dan Colen, Lexie Smith, Kunle Martins, Secret Snow, Lee Etheridge, Adam Zhu, Sasha Melnychuk, Daisy Sanchez, Louis Osmosis and Josh Foltz.