In our epoch of digital wellness, we have collectively developed a troubling habit that many are struggling to quit. Just as our obsession with clean eating has quickly spiralled out of control, many social media users are claiming to be “over-therapised” by mental health and relationship ‘expert’ creators on TikTok and Instagram, and are now unable to escape an algorithm pushing constant hot takes from therapists and life coaches on our personal issues. What was once an earnest attempt to self-improve and learn more about so-called ‘red-flag behaviours’ has since become a minefield of misdiagnosis and pathologising what are often simply unpleasant and commonplace behaviours. And as more users are recognising the dangers of over-therapising ourselves, we’re coming closer to ditching social media therapy all together.

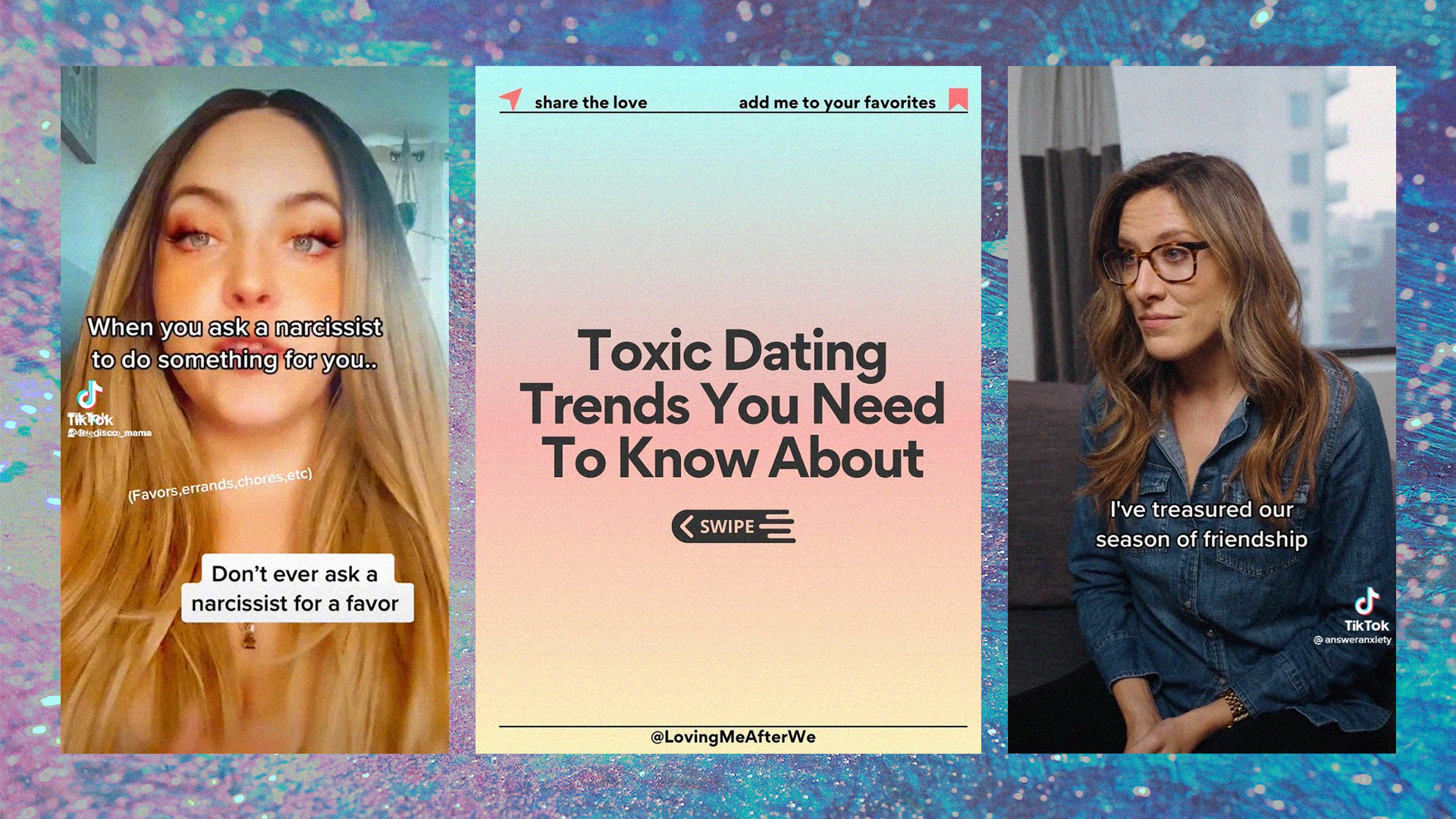

In a viral TikTok posted earlier this month — and later eviscerated on Twitter — Dr Arianna Brandolini offers her followers advice on how to break up with a friend kindly. “I’ve treasured our season of friendship, but we’re moving in different directions in life,” Brandolini suggests saying. “I don’t have the capacity to invest in our friendship any longer.” Naturally, the video was met with swathes of criticism, and commenters condemned Bradolini’s approach, calling it “patronising”, “sociopathic”, and “condescending”. Another user sarcastically remarked that “[they] too speak to my friends like an HR rep”. The backlash to Brandolini’s video, however, aptly captures our increasing ambivalence towards digital therapy.

Overly sanitised and hyper-specific, the lexicon we use online to talk about our relationships has gradually shifted to focus more on analysing other people’s behaviours and less on what tangible steps we can take to improve our own lives. Alice*, 27, says she’s noticed the more time she spent online, the more she needed to understand other people’s behavioural patterns. “When I first started following therapists and counsellors on Instagram, it was really healing,” she explains. “It helped me a lot to hear that the sort of treatment I’d experienced in relationships wasn’t normal or okay, and it felt so relieving.”

But the problem for Alice started when she felt unable to cut contact with toxic people unless she could fully explain to them why. “After watching all these videos and learning all these ideas, I became obsessed with being ‘right’ before I cut people off,” she says. “I felt I had so much insight into the ways that other people worked now that I couldn’t stop analysing them. I felt like I needed to understand why they were doing things to hurt me so often before leaving, instead of doing it sooner.”

Psychotherapist Gin Lalli explains that: “A fixation on something, anything, is the obsessional response of the primitive part of our brain. Keeping a check on something tricks the brain into making you feel safe,” she says. “In this case keeping a check on other people’s behaviours is the checking response and staying away from our own problems is shifting the focus away from the perceived threat. It’s just a safety mechanism of the brain.”

Alice says that she stopped following therapy accounts when she felt the focus had shifted from empowering their followers to encouraging them to surveil each other. “They were really helpful when it came to identifying more covert forms of abuse I’d gone through,” she says, “but they’ve since become inundated with unnecessary definitions of hurtful, albeit fairly normal, behaviours.” Examples of this included an extreme version of ghosting known as “cloaking”, and “phubbing”, where someone pays more attention to their phone than you.

“I hate labels. When we give something a label we start to define ourselves by it. This just perpetuates the condition — it’s a vicious circle,” Gin suggests. “Like a lot of things, the more we focus on it the bigger it becomes. Giving something a label, and an increasingly niche one, can sometimes make people feel special or different. In fact, the more niche the better.”

The recent critique of “chronically online” takes has similarly drawn attention to the ways in which our fixation with “calling things out” has rendered real attempts to address racism, ableism and abuse fruitless. As a recent Insider article notes, the last few years has seen terms like “narcissist” and “gaslighting” used all too liberally, often by influencers weaponising the terms at one another during online feuds. Not long after, digital communities dedicated to helping abuse survivors were inundated with new users (mis)diagnosing their partners and spouses as narcissists, reducing the personality disorder down to a casual insult and dismissing the reality of abuse that many victims face. But, as Dr Lindsay Weisner asks in a 2022 Psychology Today article, “what if the reason we have so many more hashtags about narcissists than we do diagnoses of narcissism is that it’s easier to name the demon than to claim the pain?”

Tom*, 23, says that after watching videos to get advice on a painful breakup, TikTok started to push content that actually made healing harder. “You can only learn from the past so much before you have to move on and stop ruminating, which was a mistake I made,” he says. “I was definitely hurt by the breakup, but the videos that came up were all geared towards people who’d been abused in some way or another, which I definitely hadn’t.”

“Being hurt by someone doesn’t always mean that they’ve been cruel or unfair to you, which is what a lot of these videos seem to miss,” Tom adds. “Sometimes you just have to sit with the pain and feel it, rather than looking for a deeper reason behind it. I don’t think that the algorithm really caters to content suggesting that, though.”

Social media — TikTok, in particular — fosters a culture of pushing content already familiar to users. Much like users who reported being plagued by endless tarot card readings suggested to them after enduring a heartbreak, therapy videos have found a way to continuously haunt those who may be better off putting down their phone and doing something they enjoy instead.

So, how can we go about breaking this cycle? Gin suggests making the conscious choice to stop watching and engaging with content that brings up negative feelings about our exes, partners, friends and family; instead making time for self-development with a real life therapist. “I mainly use TikTok for recipes and travel, interior, and fashion inspiration these days,” Alice says. “But if I do see anything on my FYP talking about boundaries or deal breakers, I press ‘not interested’. I feel like I’ve learned enough to ensure all my relationships are as fulfilling and happy as they can possibly be.”

While the accessibility and necessity of self-improvement content online has been invaluable to lots of us, our relationship with it — much like any other wellbeing endeavour — requires strict boundaries. Asking ourselves how necessary it really is to diagnose the people in our lives with complex mental health conditions and when to stop psychoanalysing the people who’ve hurt us is a key first step. As satisfying as it is to blame someone else’s pathology for our pain, constantly revisiting it rarely allows us to move beyond it. As uncomfortable as that can be, sometimes we just need to sit with it and sometimes we just need to leave the people who’ve hurt us behind — no psychoanalysis or HR-esque breakup speech required.