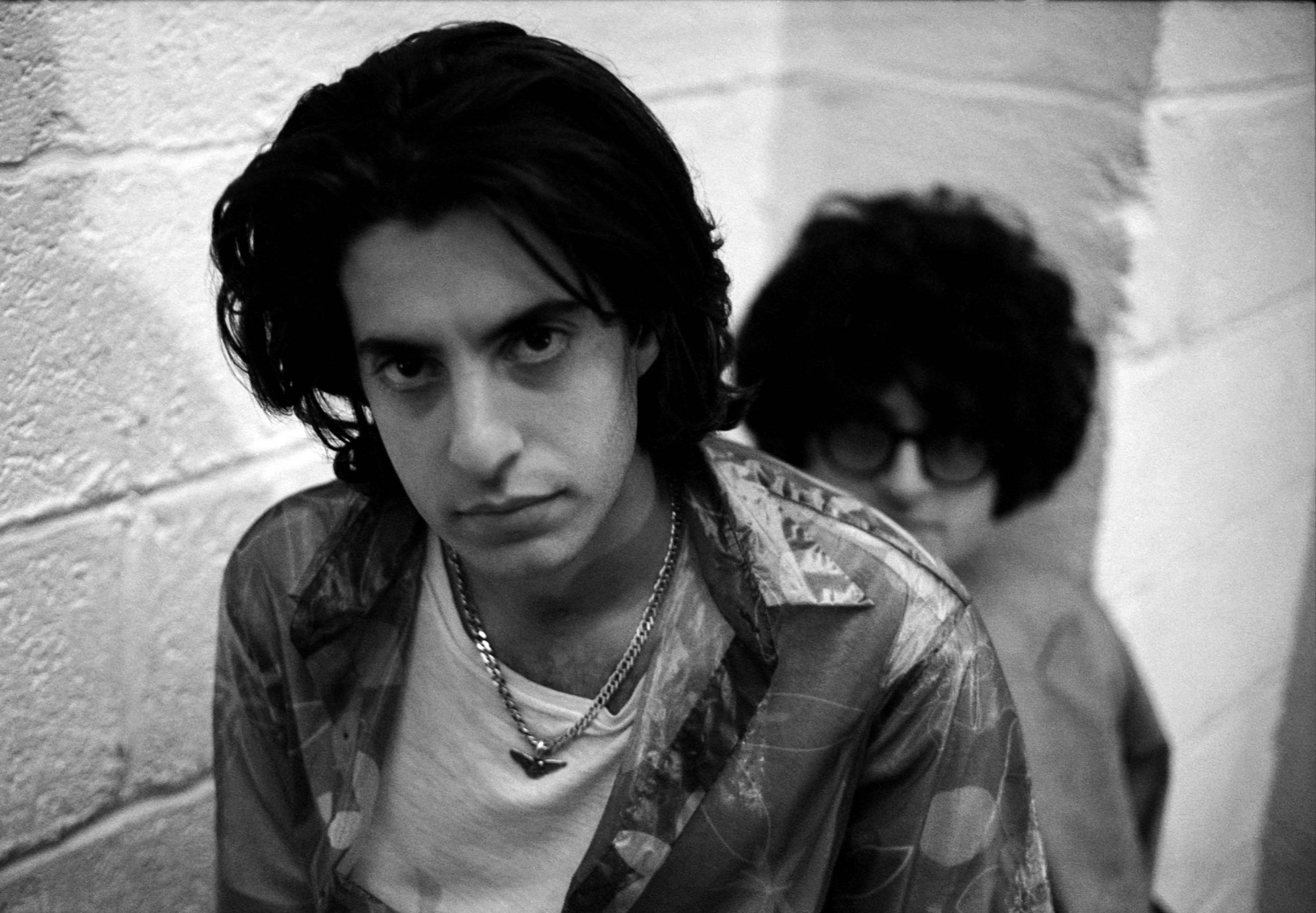

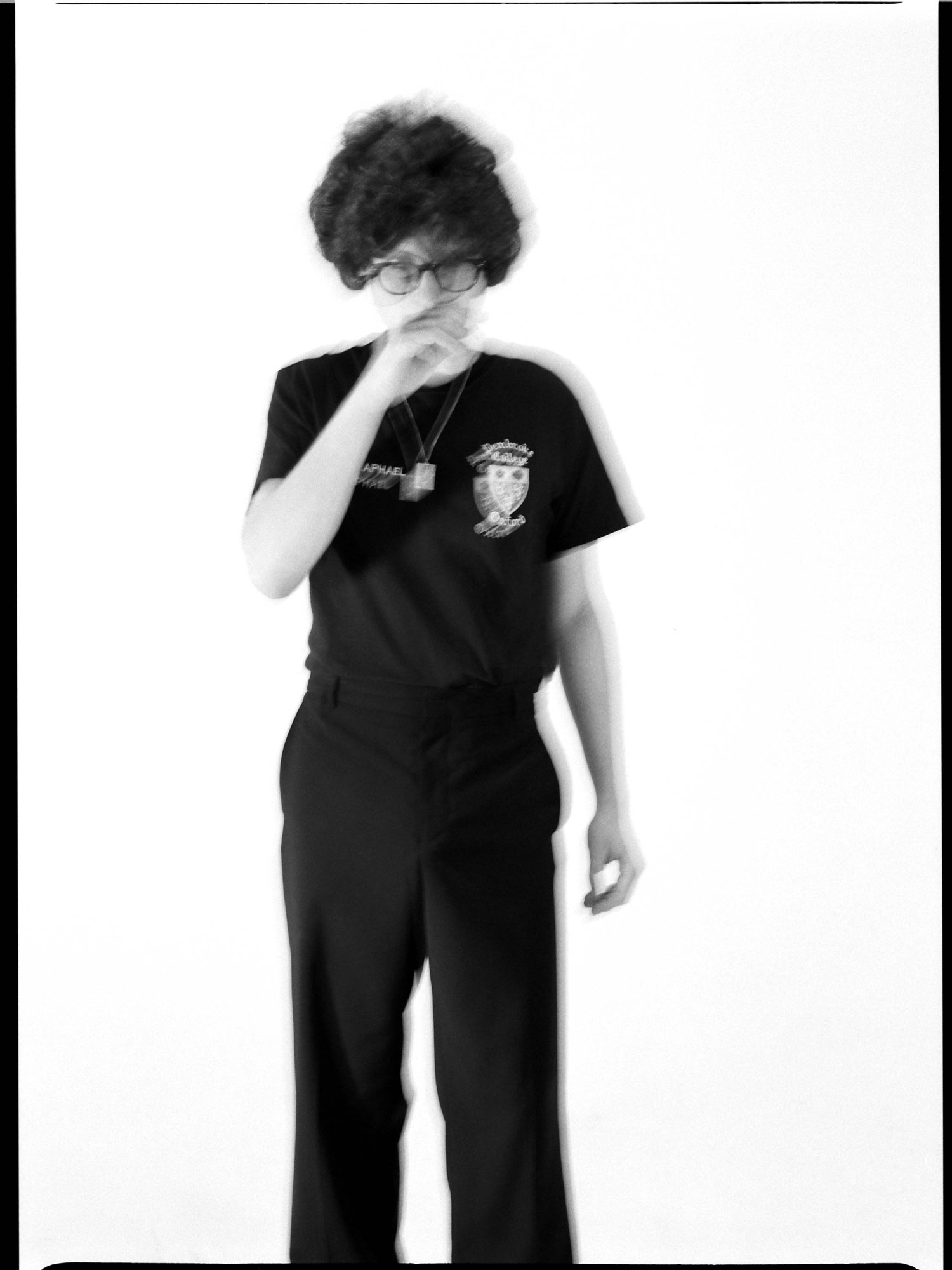

Sons of Raphael’s story originally appeared in i-D’s The Icons and Idols Issue, no. 359, Spring 2020. Order your copy here.

Sons of Raphael — brothers Loral and Ronnel — usually meet writers at Jin Kichi, their favourite Japanese restaurant in Hampstead. A quick scan of their previous interviews suggests each one follows a pretty similar formula. But today the brothers are piecing together the final parts of a new video and confronting a local dry cleaner about two ruined shirts, so we are FaceTime-ing from Loral’s flat instead. He lives a few doors down the hall from Ronnel, in a famous Bauhaus apartment block in Hampstead painted a very subtle shade of pink.

“I think we’re living by the rules of the Bauhaus,” Loral, the older of the brothers, says, of their relationship. “We share our food and we share our ideas.” Living next door allows the brothers to follow nearly identical schedules; making music, visiting Jin Kichi for soup, rising early — “sometimes 5am” — for walks on Hampstead Heath. It also allows time-out from one another, though it doesn’t seem much of that is necessary. “Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!” Ronnel quotes, effusively, from the Book of Psalms at one point.

Moving out of their parents’ house a long time ago, the pair spent most of their adolescence at boarding school, and then, in Ronnel’s case, at Oxford University. Between this, and their living arrangement, you could assume a level of privilege. Neither would agree. “I think that we’re always alert to appreciate things, we never took anything for granted,” so “no,” their upbringing couldn’t be described as such, Ronnel says.

Their parents are not Scientologists, either, despite the ubiquity of questioning about it from journalists. Yes, Ronnel’s name is derived from L. Ron Hubbard, but the Raphaels affiliation was in the name of anthropological study rather than devotion. “I think it all got a bit out of hand,” Loral says. “They’re not Scientologists or anything like that, they studied religion and cults and all sorts of things, Scientology was just one of them.”

Religion is, however, the characteristic that ties together their disparate body of work. Atmospheric, emotional, classic, the sounds they create can broadly be described as rock ‘n’ roll, but defy stricter categorisation beyond that. From their first single “Eating People” — and its accompanying video shot during a church sermon, to the first single off their new album, “He Who Makes the Morning Darkness”, which considers the paradox around creation and destruction in the Old Testament — a fixation with a monotheistic God is present in its smallest details and grandest statements. “I’ve always been fascinated with theology,” Ronnel says, “and in fact I studied it for three years at Oxford.” Thematically, religion provides a universal language for them to communicate in their music, “And I think that we write about universal themes,” Ronnel says. “God is one, I think that death is one, and love is one. It’s very simple. These are the things that will remain in the world and transcend. It’s timeless. It transcends time.”

Death, particularly, is a theme most pertinent to the album. More so than either could have realised. Having worked on it for seven years, the day after the record was finally completed, exultation soon gave way to grief as Philippe Zdar — one half of the acclaimed French dance duo Cassius, and the producer of the record — died. “We finished the record the day before, basically, and we were about to go and celebrate… we were about to fly to Italy,” Loral says.

“I think it had a big impact, first of all, on everything we did. A personal impact, but then naturally it defines things that we’ll do in the future.” We’ve got a poor connection over FaceTime, but, later that day, Loral clarifies his feelings about Philippe, writing over text: “After seven years of pain and suffering making this record, working with Philippe was actually fun, a few months of pure joy, real friendship for the first time in years.”

In typical, idiosyncratic fashion, Loral follows up with an unrelated text: “Also I’m back in business baby, the bulls won last night, by one point!!!! We’re going to celebrate at Jin Kichi now”, before returning to Philippe: “Also, when you asked about the impact of what happened – I told you that the video for ‘He Who Makes the Morning Darkness’ was about my own dilemma with faith.” The video in question, released a few months after Philippe’s passing, pans out slowly on a sign reading “GODISNOWHERE” in flames. “Most people read it as God Is Nowhere but you can also read it as God Is Now Here,” Loral says. “I’m sure it has something to do with it… how can God allow this to happen? The impact of the event is present in our video for ‘ Siren Music’ too. It features a quote from Lamentations: ‘Joy is gone from our hearts; Our dancing has turned to mourning.’ Of course that’s related.”

Before our conversation ends, I ask Loral if he still gambles — having read he once accumulated enough debt to find himself at the mercy of a bailiff. “Well, the truth is I didn’t gamble for six months,” he says. “But I was gambling on the weekend and I lost loads of money. I’ll win everything back, though, very soon, and when that day happens we’ll invite you to Jin Kichi for lunch, how about that?”

Credits

Photography Dan Boulton

Styling William Barnes

Hair Benjamin David using Oribe.

Make-up Emma Regan using Marc Jacobs Beauty.

Photography assistance Luke Petty.

Styling assistance Oisin Atiko and Alix Rowe.