Since the late 30s, Jacob Riis Beach has been a hangout for gay New Yorkers; a popular cruising location for men, that would later attract lesbian and queer women and become the diverse LGBTQ+ haven it is today. It’s only a mile long strip, on the easternmost portion of the Rockaway peninsula in Queens. An area in front of an eerie abandoned hospital — once a municipal tuberculosis sanatorium from 1915 to 1955 — near 149th Street. But the lively slither of beach has become a site for queer and trans bodies to be publicly, and proudly, visible.

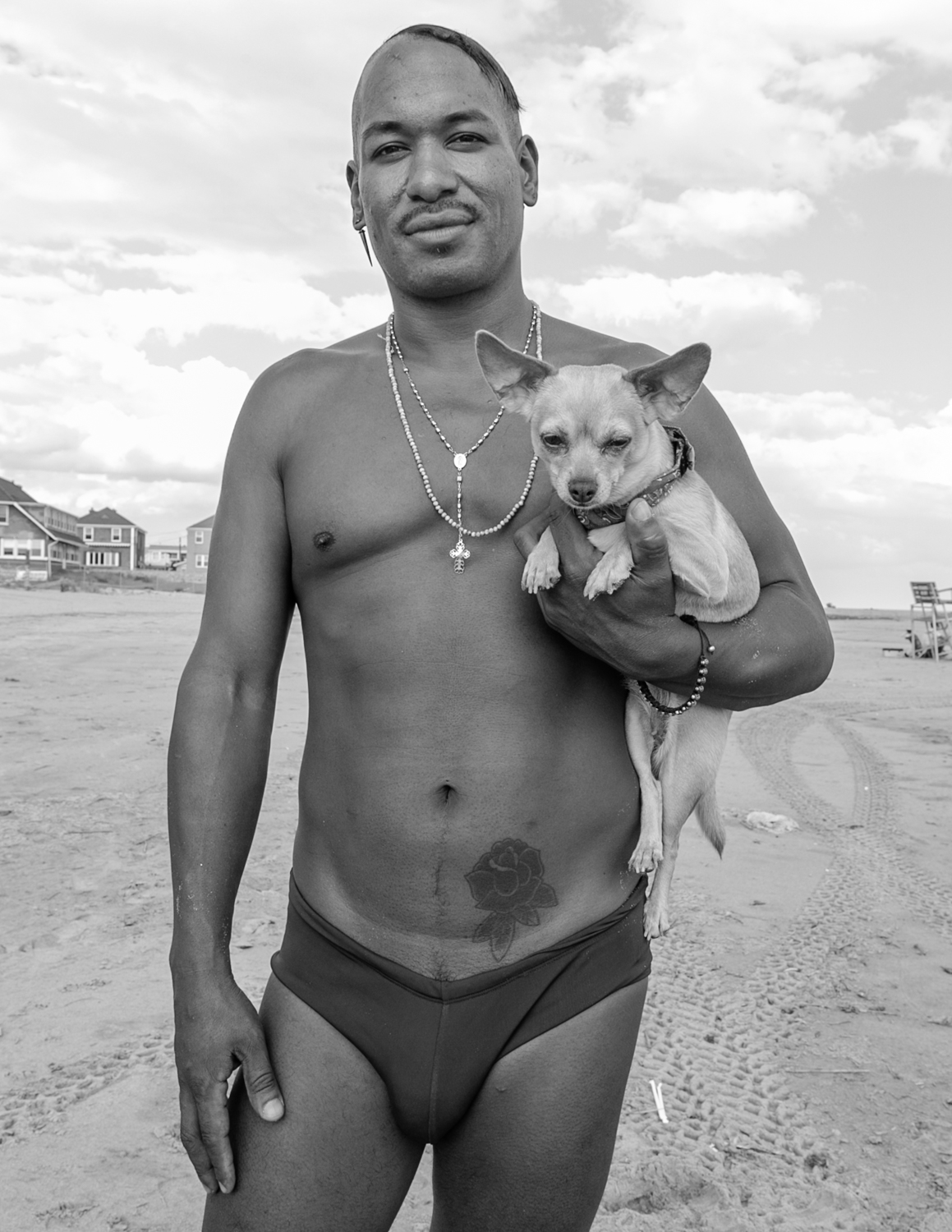

The beach takes its name from Jacob Riis, a social reformer and documentary photographer, who tried to alleviate the bad living conditions of the poor by capturing them for all to see. He’s considered to be one of the fathers of photography due to his very early adoption of flash. As such, it’s apt that a beach named after him would become one of the places to inspire documentary photographer and sociology major Stephanie Mei-Ling to spend more than a decade honing her lens on the Black and brown LGBTQ+ people that frequent it, as part of a larger project she’s working on to elevate the narratives of marginalised communities.

Born to a Taiwanese mother and Black American father, Stephanie’s biracial identity is something that heavily influences her work. But her passion for capturing people at the intersection of Black and queer society started the first year she arrived in New York. While working in retail at an apparel store in Noho called the Atrium, she made friends with two native New Yorkers who took her to Pride for the first time. It was “a magical experience,” she explains. “Just getting to witness people being authentically themselves was very inspirational. As a cis straight woman, I felt liberated in ways I never felt before.” The self-taught photographer has been every year since and always brings her camera.

Her images record the vibrant outfits created months in advance for the march, like designer Kouassi Akou’s hand-crafted dresses and headdresses in fabrics from the Ivory Coast, paired with bright jewellery. Two men in thongs with caps that read “Queen”; a drag performer in an elaborate bridal costume; and an all-pink corseted look that matches nail varnish to eyebrow and hair colour. “New York is by far the most stylish Pride,” says Stephanie, who has been to marches across America. “It’s a stylish, fashion forward city and people know they have to show up and show out.”

Like her introduction to Pride, it was a friend that took Stephanie to Riis Beach for the first time in 2008. “I’m a beachgoer,” she explains, “but being in a space that’s so loving with such a diverse presence moved me to take my camera.” That was in 2013, and she’s been documenting the queer scene there ever since. What’s interesting, Stephanie says, is the way “the landscape physically and culturally at Riis has changed over time.” In recent years, just as Brooklyn has gentrified, storms like Hurricane Sandy have destroyed parts of the coast, a citywide ferry service opened in 2017, and a free shuttle launched from Rockaway Beach directly to Riis. The demographics along the beach have changed too.

That said, summers at Riis have always been inclusive, not just for LGBTQ+ people, but for everyone. “I was embraced in this space, as a complete outsider who simply liked to tan topless in a safe place,” Stephanie says. “People of all races and sexualities have always been welcomed with loving and open arms.” But the beach means even more to the queer community. In the past, there have been voter registration drives run by The Gay Activist Alliance, and more recently, a celebration after the death of Oswaldo Gomez — better known as Ms. Colombia, a drag queen and performer known around New York for their colourful clothing. And a Black Pride is held here annually.

This year, Pride Month came around as Black Lives Matter protests swept the country. It turned the attention of the annual queer celebration towards the relationship between the fight for equality and the struggle for racial justice. Pride 2020 highlighted historic icons like Bayard Rustin and Marsha P. Johnson, who were outspoken advocates for gay rights. But despite Marsha being one of the prominent figures in the Stonewall uprising of 1969, the black LGBTQ+ community has rarely been put at the centre of the movement they helped start.

The same is true of the Black Lives Matter movement, which Black trans women have been involved in since the beginning too. In the last year, at least 16 trans people have lost their lives in what the American Medical Association has called an ‘epidemic of violence against the transgender community’. But sadly, despite suffering disproportionately from racism and homophobia that these movements aim to combat, the Black trans community has never shared the gains.

When it comes to intersectional identity, there’s often still a hierarchy that exists within race, gender and sexual orientation, at least in the public eye. This is exactly why Stephanie has focused her lens on these communities — in the hope that she can take visual representation beyond the archetypes and stereotypes that are so common in popular culture. “I’m careful to really connect on a human level and find honesty and humanity in my subjects,” she says.

“A lot of us have been highly aware of the disparities and constant injustices on every level,” Stephanie continues. “I’ll take any form of change and acknowledgement because it’s a step in the right direction, but there’s a part of me that wonders why it took so long.” On whether she thinks the protests this year could be a turning point in the quest for real equality and racial justice, she says that there’s a part of her that’s skeptical. But she’s confident that the youth will pave the way for change.

“[I have] a lot of faith in the younger generation who bring with them a different type of protest,” she says, “one with a lot of tenderness, a lot of love, a lot of music and dancing and celebration.”