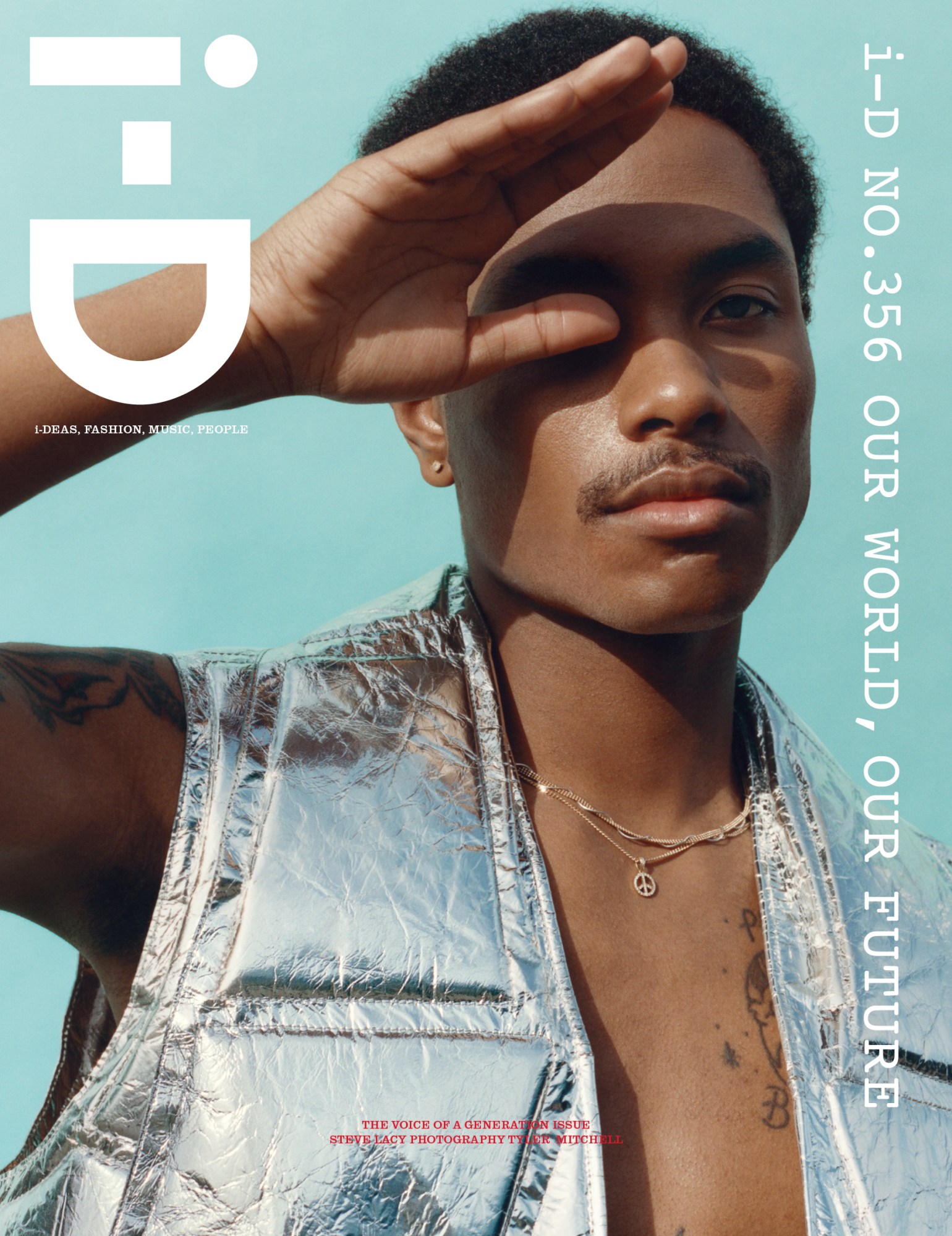

Steve Lacy’s story originally appeared in i-D’s The Voice of a Generation Issue, no. 356, Summer 2019. Pre-order your copy here.

20 miles north-west of central Los Angeles, somewhere between Malibu and Pacific Palisades, lies the quiet, secluded Topanga Canyon. Verdant and lush, largely untouched by developers and enclosed by the city’s largest national park, Topanga has been a locus of musicians seeking refuge from the chaos of Los Angeles and a great source of inspiration for decades. The quiet bohemia of its rolling hills and rocky lanes notably shaped the work of Neil Young’s solo career. He recorded much of After the Gold Rush at his Topanga home; a studio at the heart of the area’s music scene in the 60s. During the same period, The Topanga Corral, a roadhouse patronised by the likes of Janis Joplin, Canned Heat and Jimi Hendrix, was said to be Jim Morrison’s inspiration for Roadhouse Blues. It’s where Steve Lacy is when he takes this phone call.

Steve is currently taking some time to relax and think about his next step. “I’m just relaxing… that’s about it,” he says. He’s in a beautiful headspace right now. “Everything’s crystal clear. I’m not really worried. I don’t have expectations for anything.”

Having just returned from a world tour with his band The Internet, soon to release a highly-anticipated debut album and about to turn 21, there’s plenty of things to be excited about in Steve’s life at the moment. Yet the only thing he can think of right now is the new bed he’s just bought. “Just the bed. I’m not really excited for that much else… you know?” an inflection that follows most of his answers. “I only focus on one thing at a time. I don’t think too far ahead, I take everything step by step. The future gives me anxiety, so I just stay present a lot of the time.”

Steve grew up a few miles south of Topanga, down the Pacific Highway and along the Santa Monica Freeway, in Compton. He was raised by his mother, has three sisters and a father who was largely absent from his childhood. “It was a pride thing for him,” he says of his dad. “He felt like he had to have something to come around us. I mean at least that’s what I’m told. He only came on holidays, birthdays, just when he had some money or something to show.” At age ten, his father passed away, but “no”, his death didn’t have a big effect on him or his family. His mother had another child, the third of his sisters, with a new partner. “We were middle class, it was comfy, it was cosy. Church on Sunday and stuff like that.”

Steve’s mother wanted him to be safe from the more nefarious aspects of life in Compton. He attended a “nice, intimate” private school from kindergarten to sixth grade and wasn’t allowed out much during his childhood and early teens. “I call it, like, a hood suburb, that’s what it feels like to me. It was definitely a lot worse growing up and I grew up very, very sheltered because my mom was afraid I would be part of illegal activities or get hurt or something. I couldn’t really play in the front yard. I couldn’t do a lot of things. I couldn’t hang out. I never had neighbourhood friends, I never could go to like all the parks my friends would go to, I didn’t really get to leave. I mean, I got to leave but I didn’t really get to branch out on my own. It was very sheltered.”

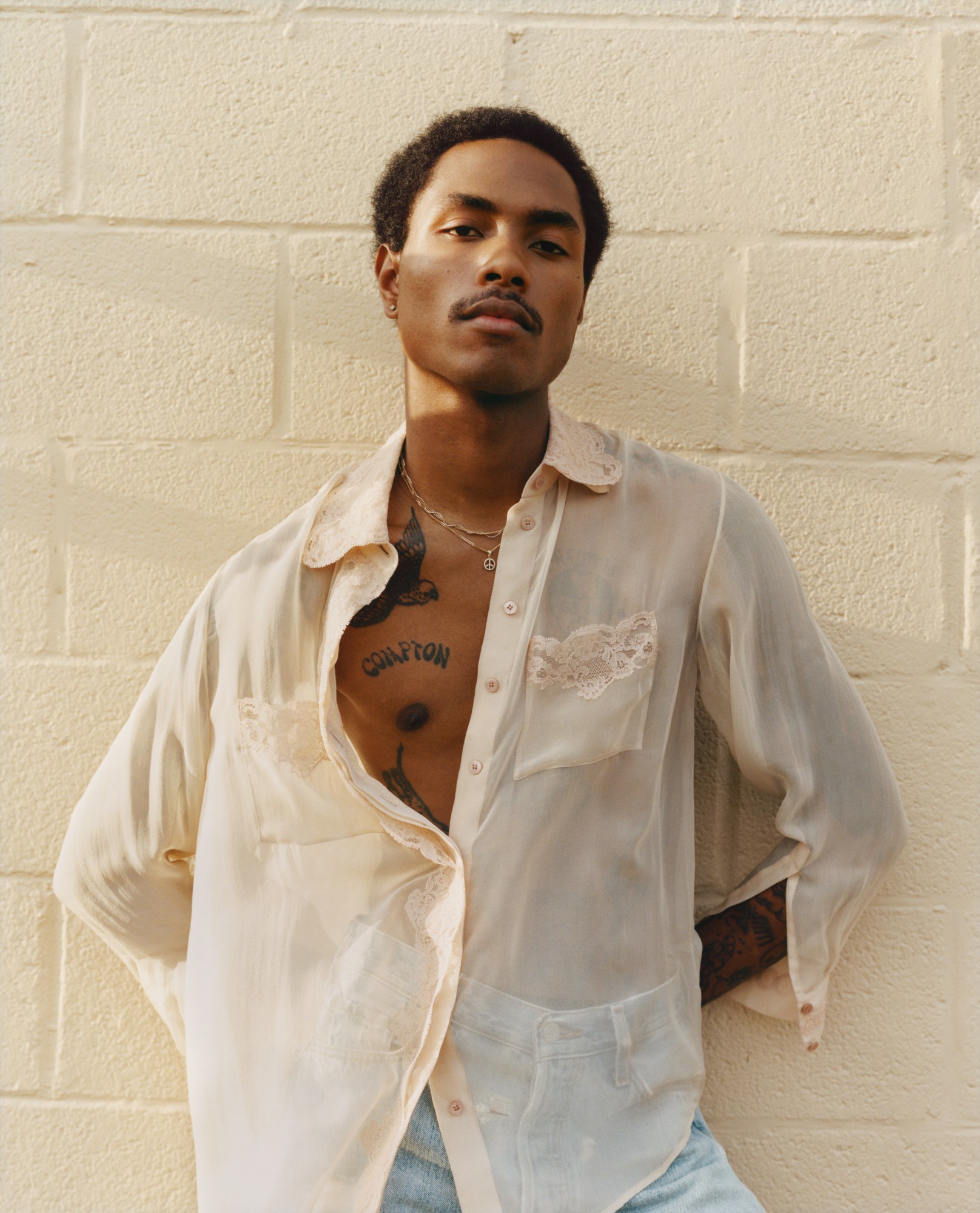

Steve is quick to point out that the stereotypical image of Compton that dominates the public perception, its streets, its neighbourhoods and its communities, are completely warped, exaggerated and inaccurate. “It’s not just the Compton portrayed in, like, Boyz n the Hood, that was years ago. The image painted of Compton is very negative. A landmark of Compton is a damn courthouse, that’s fully fucking sad to me.” Such is his pride and respect for his neighbourhood, the word “Compton” is tattooed across his chest.

At age ten, Steve began playing the guitar. “At the time that I picked it up I was just in love with it. It was just cool I was playing a lot of Guitar Hero, and then it was like ‘Ok, I need the real thing now’.” At high school he joined the school band and met Jameel Bruner, the keyboard player for The Internet at the time, and what ensued is nothing short of musical history. Steve soon began work with The Internet on their third album, Ego Death. Fronted by Syd tha Kyd, the album won critical acclaim and a Grammy nomination for its sharp lyricism as well as the clever production, in which Steve had a big hand. Pitchfork described it as “an offspring of early neo-soul pillars like Groove Theory and Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite, bedroomy but also lush and progressive”. Rolling Stone noted that “The best tracks fade away into gravity-defying instrumental outros that make Syd’s heartache feel sublimely serene.” Steve wasn’t able to tour the album with the rest of the band. He was still in school.

One of the resounding qualities of Steve’s talent, picked up with wearisome repetition by music journalists and projected across hyperbolic headlines, is the fact he’s the “iPhone producer”, teaching himself to produce using little more than an iPod Touch. As he explained in TEDxTeens talk back in 2017, each Christmas throughout his teens he asked for a Macbook, but never received one. Instead he created beats using apps like iMPC, BeatMaker 2 and GarageBand on the iPod. Between his guitar, his bass, and these apps, Steve had everything he needed to create something totally unique. The accolades soon followed, as did call-ups from Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole and Denzel Curry to work on the production of their albums. “They’re all just nice, well-rounded, smart, talented people,” he says, of what he learnt sat in studios with such illustrious names. “They pretty much ensure that I’m one of them. That’s probably the biggest thing that I’ve learnt… that I’m one of them. I didn’t feel any different around them, intimidated around them, you know? We were just cool. Just human.”

Next came Steve Lacy’s Demos, his debut solo project. Also produced largely on an iPhone, Steve sang vocals straight into the microphone. Dark Red, the mixtape’s lead single, currently sits at 27 million streams on Spotify, and he’s since featured on tracks with Tyler, the Creator, Frank Ocean and Blood Orange. Most recently Steve appeared on a Vampire Weekend single, the band’s first ever guest-feature on a track, and has credits on Solange’s new album When I Get Home, one of the most intriguing musical projects of the moment.

Working with Solange was “cool”, Steve says. “She was open… open to all of to my ideas. I remember there was this one time where I had this chord progression that was very, very tedious. I was so nervous, because it was the first time that I had met her, so I’m like oh man, and I’m like fucking it up, and she’s like no, no, don’t worry, and she turned the mic up to my face because I’m playing this like, this chord progression, she was just very open and calm, I ended up getting it out. It didn’t make the record but that was a fun moment.” When asked why he thinks a 20-year-old kid has picked up so many illustrious credits, Steve hazards a guess at being “kind of good at music”, and “just being… cool.”

Work began on his debut solo album about two years ago. “My little sister moved to college and I had her room to just do whatever with, so I put a studio up in there, and I just, you know, made music. I had a break from touring for like a month and a half, and I was literally just recording.” Amongst all the work for other artists, at no point did he struggle to fully define his own sound. “The music I make with someone else… It’s a different energy. It’s never going to be the same”. His method is to remain as adaptable as possible. “I like to be a chameleon, blend into any situation I’m given, whether it’s musically, or with life. It’s cool, I just like to read them, and their personalities before, and like present an idea… you know?” The only thing that’s really changed in the past five years is the equipment he owns. “I’m not as limited to resources anymore. I’ve made a little money, so I have a laptop now and some instruments. I think the process is still the same, I’ve just got some better gear that’s all.”

The album traverses different emotions, styles and iterations of Steve’s persona. Its lead single, N Side, sets the tone for the album, Steve’s floating lyrics across a laid back tempo. But it’s the second track, nine-minutes long and divided into three separate segments, that undoubtedly cause the most commotion. Sonically, it’s huge. “It was kinda like a middle finger to the people who were like, you can’t make this song longer than three minutes and I was like alright I’ll give you nine minutes, how’s that?” But amongst the grandiosity of this, there’s great intimacy in its lyricism. “It’s basically my journey, my sexuality. But in a very fun and witty way, it’s not really that serious, it’s not super sad. I think it’s my journey, it’s an expression of how I feel right now.”

Discussion of Steve’s bisexuality has been a feature of his interviews for a little while now. Unsurprisingly, it’s something he doesn’t want to define his solo career, though he agrees it is a landmark moment in an industry still unfamiliar with this story. “I’m not really that bothered by it honestly. I don’t like to look at it as a big part. Um, and I think, who we’re fucking, shouldn’t matter in the world. It’s kind of silly to me. But I’m also speaking from my Los Angeles bubble, I always have to be cautious of that. I don’t like to make it a big deal. I don’t want people to look at me..” he trails off, “you know, I don’t know, I don’t know.”

The bubble that Steve occupies is not just an LA one, but increasingly a bubble filled with some of the biggest artists in the world. “I don’t think anything’s changed,” he says. Walking for Louis Vuitton and appearing in their campaign, combined with an Instagram filled with selfies that get north of 100,000 likes, to some his swift, defiant ascent from behind-the-scenes producer and guitarist to global star and heart-throb has changed pretty much everything. “I think as soon as you’re a famous person the human aspect kind of disappears — people just see you as that being. So I’m trying to balance those two things. Those things kind of go in one ear and out the other. I guess it is cool, yeah. I don’t know… I don’t see myself as anything. But this is a magazine cover issue, so maybe I should say something like…” He pauses a little longer. “It’s cool.”

Credits

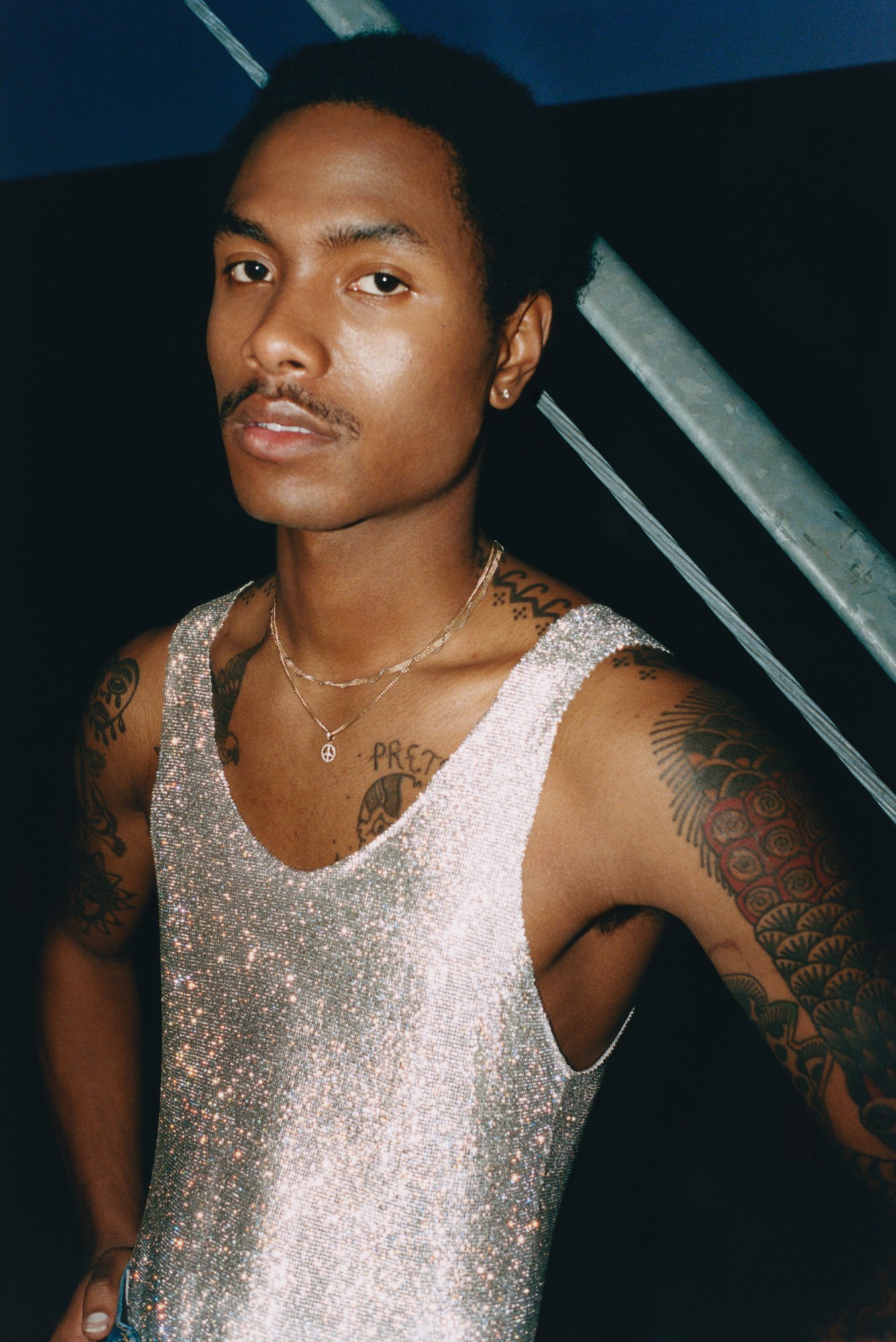

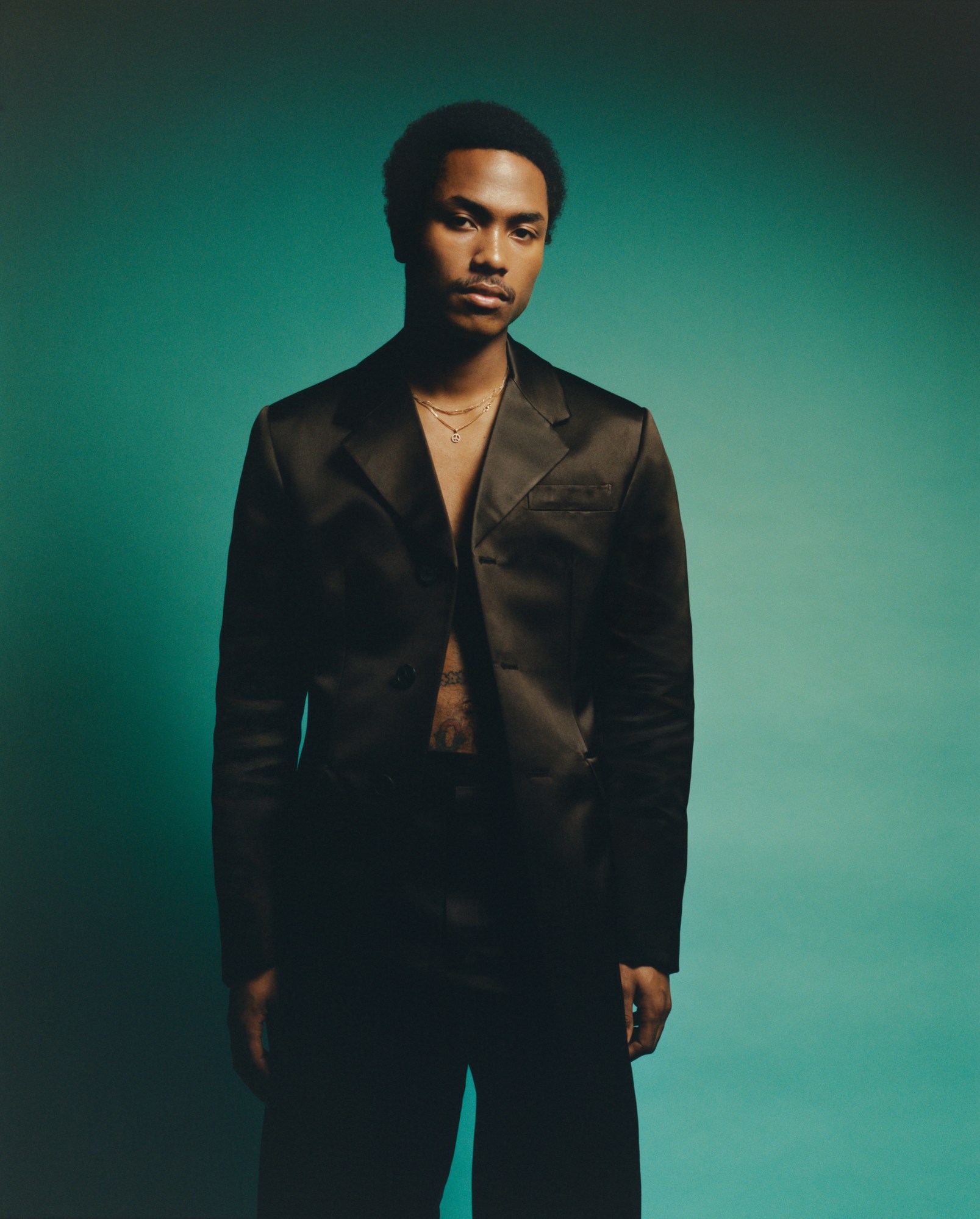

Photography Tyler Mitchell

Styling Carlos Nazario

HAIR Ronnie McCoy III. Make-up Sarah Uslan. Set design Mila Taylor Young at Dandy Management. Photography assistance Zack Forsyth and Daniel Marty. Styling assistance Christine Nicholson, Ramond Gee, Jose Cordero and Elyse Lightner. Tailor Susan Korinian. Production Connect the Dots. Analog printing by Natalie Hail.