Harmful stereotypes about Hispanic people are alive and well in 2018. NYC photographer Stephen Velastegui is less concerned with our president’s overtly racist remarks and offensively sad taco bowls, and more interested in the unspoken nuances that exist within his own community — especially those concerning masculinity and queer identity. He lists examples: calling the guy in the bodega Papi, wrestling bros in locker rooms, and qualifying displays of affection with the classic “no homo.” Velastegui recently received a text message from his barber calling him “pretty boy” after the older man had come across his Instagram stories. Better than “faggot,” the younger boy reasoned.

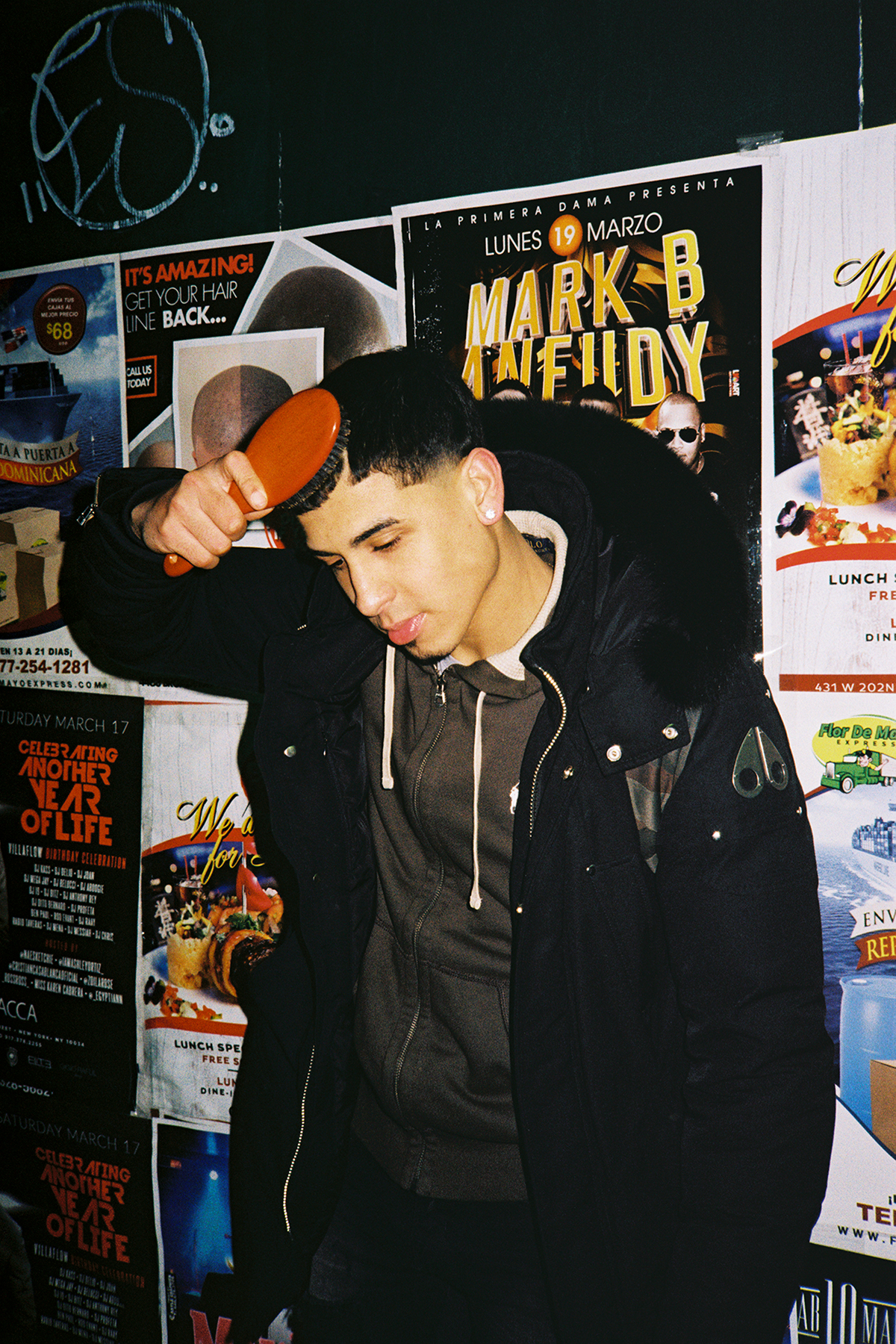

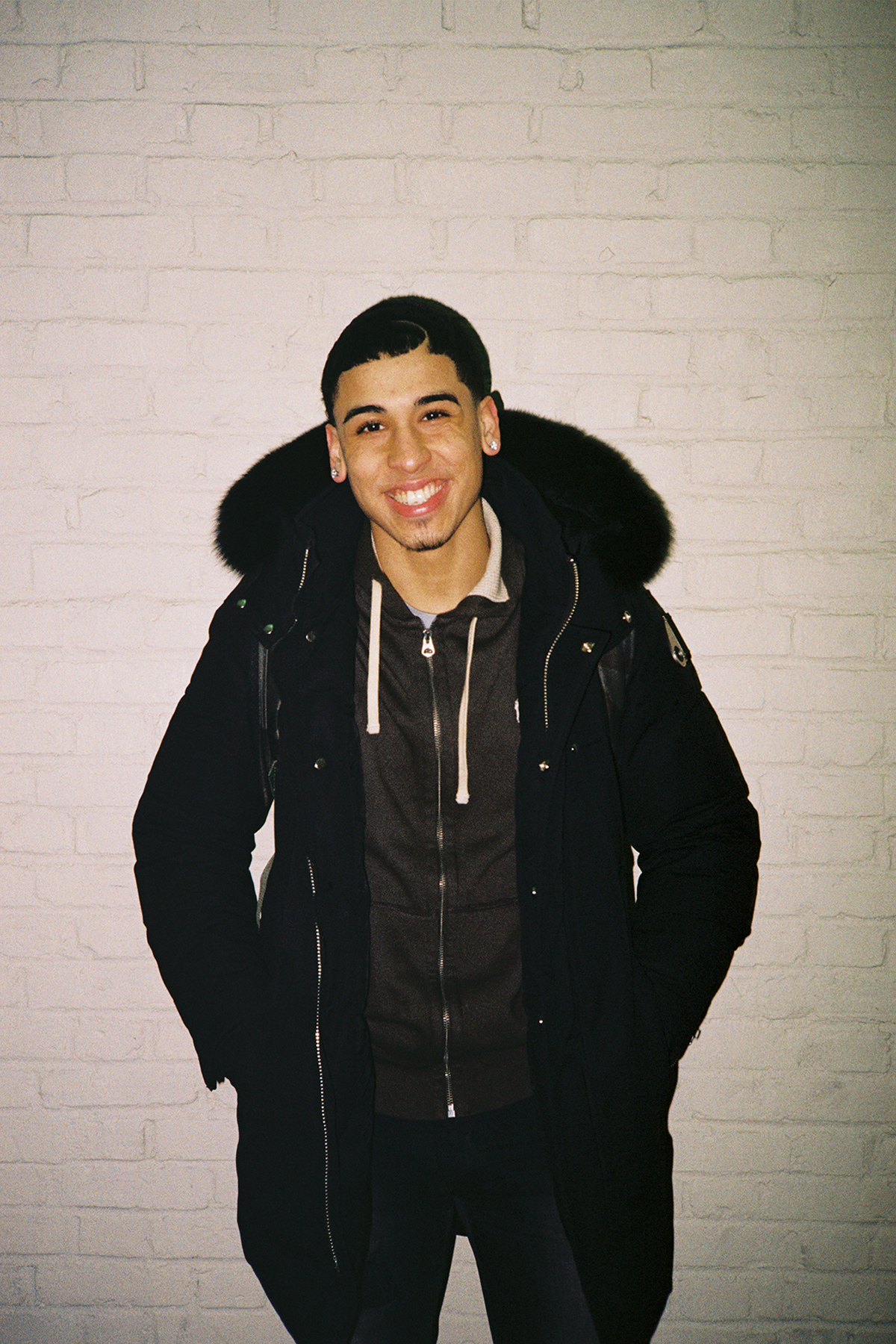

These encounters Velastegui had with other men, both sexual and platonic, inspired a project that questions how Hispanic boys’ upbringing and environment shapes their relationship to masculinity and other men. He started photographing NYC-native Hispanic boys from Dyckman, Inwood to Ridgewood, Queens. One chain-wearing teen leans against the graffiti covered façade of Affordable Used Auto Parts on Wyckoff Ave, another fixes his hair in front of wheatpaste promo posters for El Alfa el Jefe and Miriam Cruz. Monochromatic streetwear is a backdrop for more subtle visual cues: fresh fades, chain necklaces, and a tiny rose tattoo behind a diamond-studded ear.

“My goal is to question the source of my brothers’ behavior, both gay and straight,” Velastegui says of the project, “and to further define what homosexuality and masculinity mean to me.” His own experience as a young gay Latino, though, has been a pretty positive one. Velastegui explains that “the notions about being ‘normal’ that have been sewn into Latino households for decades have provided me with a dynamic sense of agency within my own identity.”

i-D talked to Velastegui about prejudice, gender performance, and growing up in NYC.

When did you start to become aware that you didn’t fit the stereotype of a young Latino man?

Growing up, I always knew that I exerted more “feminine” traits than other boys, but I felt comfortable in my body and with my sexuality. As a result of my environment, this changed a bit as I got older, but it was more of a settling into maturity. I started to realize that no matter much I was attracted to the masculine Latino boys around me or how interested I was in the same things as them, I could never exist merely as one thing. I’m a very absorbent person, so I am constantly being influenced by the things around me. I also experienced a gentler treatment as a gay Latino man growing up, compared to others around me, which I now recognize as a privilege during my adolescence as acceptance varies from place to place.

Barber shops have historically functioned as sacred places in minority communities. What place have they held in your own life? Has this changed as you’ve grown older?

Barber shops to me are one of the strongest double-edged swords in our communities. They mold young boys into grown men, as life lessons and experiences are passed on seat by seat, and they are also safe spaces for us to express our ideas unabashedly. However, this exchange of perspective also invites the stigma and internalized homophobia that are deeply embedded into Latino cultures. A lot of older heads believe that “being a man” means being nothing but straight, masculine and violent, which could be a detriment to our younger generations, but it is our job to engage in the processes of unlearning and reteaching the truths about manhood and sexuality.

My barber shop is still my savior, though. My haircut requires very high and frequent maintenance, so I’m always in the chair. Real New York boys get a cut every week! Additionally, I never considered their socio-economic contributions until I got older, but I have a great appreciation for barber shops because their cash-only practices employ the men of our communities, while subverting typical business operations.

How does social media/Instagram provide a space for you to navigate your identity, if it does at all?

Social media is really interesting in the sense that I’m able to exhibit my identity, for free, on a platform where I am in control of how I am represented. I get to showcase different parts of myself, and test how they are all received by the public. Instagram is one of my favorite spaces to show my process/new work, as well as to connect with like-minded individuals and exchange our perspectives with one another. The real-life relationships I’ve built from social media have provided me comfort in being myself and have helped me build my personal network.

When talking about this project you mentioned phrases like “ayo” or “no homo” being used to qualify feelings. How does this contribute to the prejudice LGBTQ hispanic boys face today, and how they interact with other males?

The context in which terms like “ayo”, “pause,” and “no homo” are used is to imply that a man is gay, and that he should feel shame for being so, and for saying whatever incited the “call-out”. Having grown up in the New York City public school system, I’ve witnessed this on a daily basis. I’ve also witnessed boys pretending to engage in sexual acts with one another, as well as performing impressions of what they think a gay man “sounds like.” These nuances trivialize the way we navigate our sexualities/identities by associating it with shame, making us the “other.” This also has a negative impact on DL culture. Latino men, especially in New York City, are so terrified to be themselves due to family/community ties, which often leads to unhealthy and sometimes toxic sexual relationships, further perpetuating the stereotype that we are sex-crazy.

How do these stereotypes affect how you interact with women/girls?

Oddly enough, and I’m sure this experience is specific to only me and maybe a handful of others, these stereotypes have made it rather easy to interact with both women and men. A commonality between myself and the Latino men I currently have relationships with is that as we grow older, we become more accepting. However, I find it easier to fully be myself around a group of women than a group of men. I find myself always having to be the “man” when I’m with a bunch of other girls, but feel obligated to assimilate to masculine behavior when I’m around other guys, like dapping instead of hugging, and unconsciously deepening my tone.

How do you use visual cues and fashion to conform to or challenge stereotypes of masculinity?

A lot of what I incorporate into my personal style draws reference from my upbringing in Ridgewood, Queens. Russell sweatpants, Air Force 1’s, Carthartt coats, and skin fades are all cues that I take from what I grew up around. But although I dress rather masculine, I like to feminize what I wear with gold accessories, specifically name jewelry. For this project, I was sure to scout both masculine and feminine boys whose styles varied significantly, but that I saw a little bit of myself in. We’ve been lucky enough to see a broadening in representation of marginalized groups over the last few years, but I wanted to illustrate that not every Dominican from Dyckman or Mexican from Bushwick looks the same. Papi Chulo as a result features boys who conform to, counter, and subvert the traditional stereotypes of masculinity.

How do you think Latino boys are perceived in New York City as opposed to in other parts of America?

I think Latino boys in New York City are generally perceived better because there is so many of us. Although there is a significantly larger number of Latino men in NYC than in other states, there is still the common assumption that we are uneducated, because our younger generations take on jobs in physical labor industries like engineering, contracting, and custodial duties; we are also assumed to be sexually deviant and hyper-athletic. What some people fail to realize, even progressive-thinking New Yorkers, is that people are products of their environment, and discriminatory displacement plays a huge role in the quality of some our brothers’ lives.

What was the reaction of the boys you shot for this series when you asked if they’d be involved?

Just as positive as I expected it to be! Finding subjects for Papi Chulo wasn’t difficult at all, but finding subjects who could commit to a shooting schedule was. Ultimately, I couldn’t be happier with the boys that sat for these photographs and allowed me to share their experiences with the public. I have no other feelings about this work than gratitude and humility. Shout out to Daniel, James, Lucy, Jaidev, and Gustavo!