Even four years ago, a large-scale institutional show dedicated to what is widely known as internet art would have been unimaginable. But as a whole generation of practices mature, along with theory and criticism to match it, digital art seems now to be in high institutional demand: last year’s triennial at The New Museum and the Nordic Biennale were both examples of this. However, Electronic Superhighway (2016 – 1966), at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, seems to be the first attempt to establish an authoritative historical genealogy for the plethora of practices that operate in and around the digital. The show’s bold claim is to account for nothing less than “the impact of computer and internet technologies on art through the last 50 years.”

The exhibition begins, strangely, in the present. The Whitechapel have reversed the temporality of their canon – beginning on the ground floor with contemporary works from the past five years, then moving backwards in time to early net.art of the 90s, and ending with 70s video art and early drawing-based cybernetics. This gesture seems particularly appropriate for the mediation of internet art, which, rather than chronologically, is experienced through the vertically-scrolling temporality of the web, of Instagram and Facebook – where many of these practices were first discovered and honed.

The exhibition presents an almost exhaustive overview of contemporary internet art. Ryan Trecartin, Petra Cortright, Cory Arcangel, Douglas Coupland, Jan Rafman; all those big guns are here, each presenting their own treatment and critique of the internet, and its impact on artistic practice. An incredible collection of over 70 artists have been squeezed into Whitechapel’s modest halls, but in this overcrowded labyrinth, it was difficult to take the many ambitious works for more than face value. Hito Steyerl’s triptyque of Mac Minis glowing in red – signaling the highest level of national vigilance, while echoing Alexander Rodchenko’s modernist formalism – drowned amongst brighter or louder works – and to great disappointment, Katja Novitskova’s digital animal print was parked in a corner, preventing its aluminum surface from revealing its true sculptural shimmer. This curatorial problem, of course, is symptomatic of art in the internet itself: the difficulty of surviving the maelstrom of the uncurated feed and fighting for the right to circulate.

Except three darkened video-rooms, the ‘now’ section of the exhibition was represented in a surprisingly conventional white-cube format. Amalia Ulman’s performed Instagram-persona in Excellences and Perfections radiated from a toilet-selfie, strangely enlarged from iPhone screen sized to over a meter in width. The question lingering over such a survey is whether this institutional representation serves the purpose of the work? Excellences and Perfections excels because it depicts the young woman online in complete aesthetic control of her own representation, constructing an impeccable image in the size and quality appropriate for its network of circulation. Like much of the works, Excellences and Perfections, loses as much as it gains in the tumult of The Whitechapel’s Galleries.

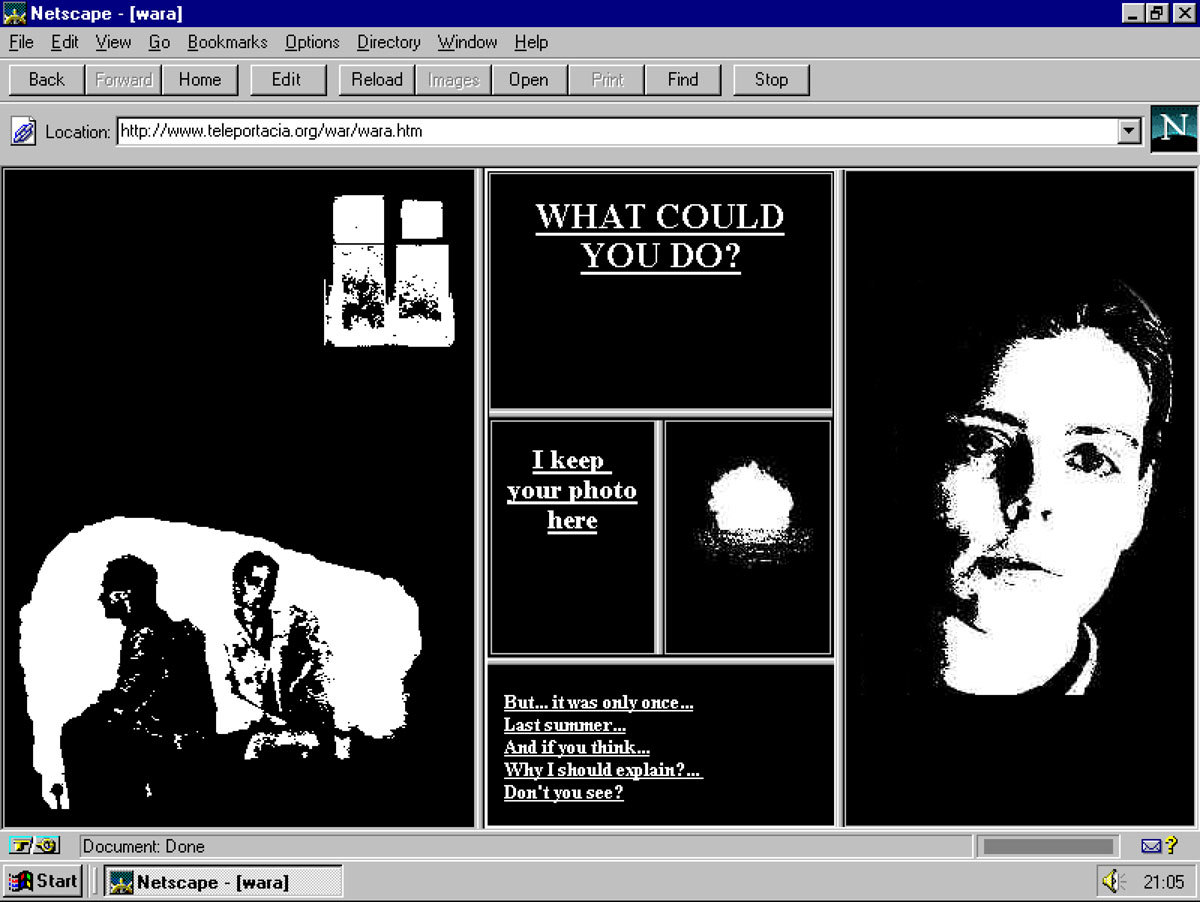

In contrast to the sensory overload of contemporary work downstairs, The Whitechapel’s upstairs galleries took on a more historical tone with gray carpets, dimmed lights, and a much less cluttered mise-en-scene. The hacker-esque self-imagination of early net.art crystallised in a series of interactive browser-based works from the Rhizome archive, which began immortalising the very first born-digital artworks in the 90s. Olia Lialina’s touching interactive work My Boyfriend Came back from the War was appropriately installed on a chunky stationary computer with an adjusted bandwidth, simulating the same rhythm and durationality as when it was initially presented in 1996 (a curatorial concern the Russian artist has previously expressed). A kind of third avant-garde, the Web constituted for net.artist a radical utopia – in stark contrast to the corporatised digital dystopia discussed by artists today.

Two final rooms juxtaposed vanguard 70s video art, by conceptualists like Robert Rauschenberg and Yvonne Rainer, to archival fragments of the seminal Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition from 1968. This juxtaposition highlights an important art historical discussion on the genealogy of Internet art: is it conceptual art’s heightened sensibility for space and time that laid the foundation for today’s Internet practices, or was it rather the ethos of 60s futuristic communication theory? The answer is, of course, a combination of both. However, the linkage to conceptual video art is only beginning to unravel in a time dominated by new media theory – and here, the video archive, which was sourced from the 1966 exhibition Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T), offered a valuable viewpoint.

A virtual who’s who of Internet art, Electronic Superhighway ticked all the boxes in terms of canonic name-dropping, yet it felt rushed and cluttered, and seemingly conducted so as to get this kind of art ‘out of the way’, to move on to something else, and quickly send these works back to the specialist archives. The internet, of course, has changed art forever – as Jesse Darling once posed, “all artists working today are post-internet artists” – and this will hopefully be recognised in many more institutional exhibitions to come.

Electronic Superhighway (2016 – 1966) is at The Whitechapel Gallery until 15 May 2016

Credits

Text Jeppe Ugelvig

Main image Nam June Paik, Internet Dream, 1994. ZKM Collection© (2008) ZKM Center for Art and MediaKarlsruhe. Photography ONUK (Berhard Schmitt)© Nam June Paik Estate