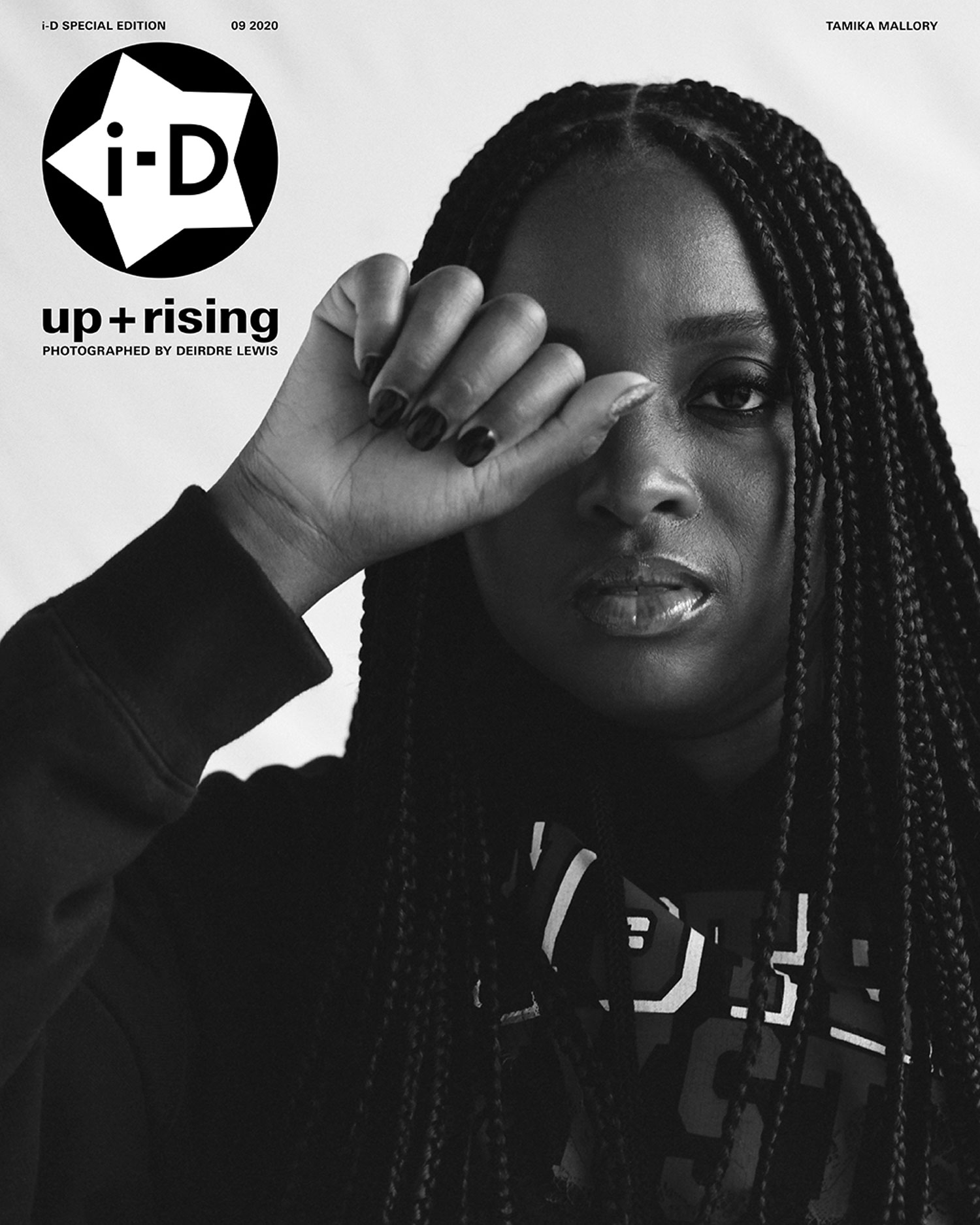

This story originally appeared in Up + Rising, a celebration of extraordinary Black voices, and is the first chapter of i-D’s 40th anniversary issue (1980-2020).

i-D chronicled over 100 activists and artists, musicians and writers, photographers and creatives, in Atlanta, Baltimore, Minneapolis, LA, London, New York, Paris and Toronto.

At the time that this article was written, it had been 175 days since Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black female emergency medical technician, was fatally shot by Kentucky police officers while sleeping in her home. During this time period, no charges had been brought against the cops responsible for her death and little information had been provided from the prosecutors office to satisfy her family’s incessant cries for justice.

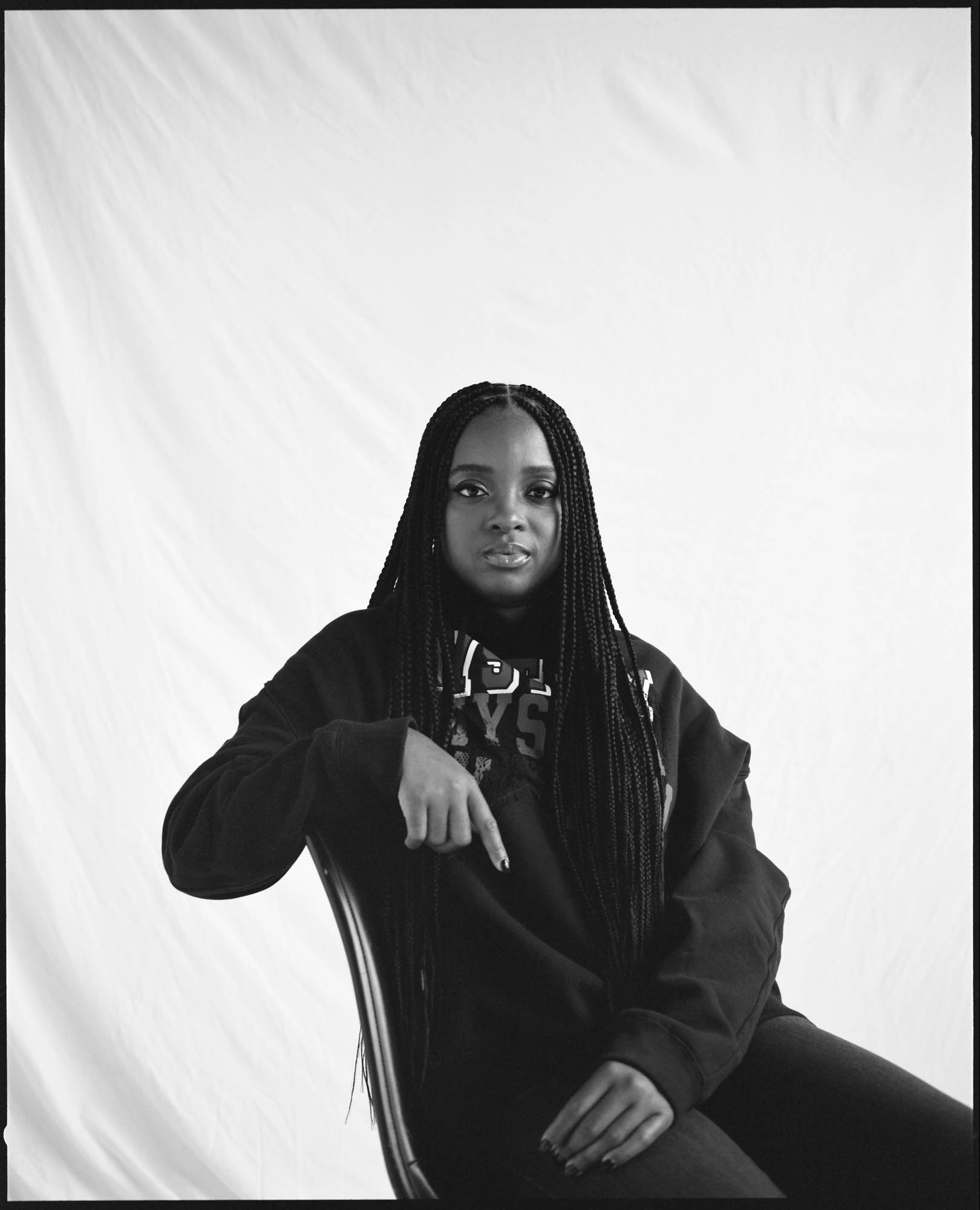

The unsettling reality of “delayed justice” and the lack of accountability shown by Kentucky prosecutors has also failed to appease activist Tamika D. Mallory, who over the past few months has worked tirelessly alongside Taylor’s family protesting and talking to public officials, all in an effort to convince prosecutors to arrest and charge the cops that killed her. As one of the leaders of the 2017 Women’s March and the Founder of social justice organization Until Freedom, Mallory’s commitment to advocating for Taylor is symbolic of her intersectional approach to activism that prioritises centering the voices of women.

“If for some reason we thought that we were living in a post-racial society, or that things were getting better, Breonna Taylor reminds us of just how bad things still are,” Tamika says. “If you ever had a question about the level of racism that is in the criminal justice system in this country, this is a clear example of such. It is institutional. It’s not just the courts, but it’s the courts, it’s the police departments, it’s the way in which the entire system operates and a Black woman is being discarded as a result of that system.”

The unequal criminal justice system that Mallory speaks of is one that, for years, she has been fighting to not simply reform, but completely overall. At an early age, Mallory recognised the role that racism and poverty played in the unjust prosecution and imprisonment of the Central Park Five, New York City teenagers that were unjustly accused and convicted of raping a white female jogger. “I knew from nine years old that my race could literally be the thing to either get me killed or locked up for the rest of my life for a crime I didn’t commit,” says Mallory.

It is the names of the Central Park Five and the dozens of other Black victims, either unnecessarily murdered or imprisoned by police, that run through her head when making impassioned speeches like the one she gave in Minneapolis during a rally for George Floyd, an unarmed Black father killed by police in May. This was the speech heard around the world about a crime that, because of its violent nature and it being caught on video and published online, has fuelled an unprecedented response from individuals and organisations that have pledged to change the way the world supports and advocates for the rights of Black people.

Since Floyd’s death and her speech going viral, Tamika Mallory has been championed as one of the leading voices of the Black freedom movement. Her “close knit” community of 200k engaged Instagram followers that she considered close collaborators in her evolution as an activist, is now a community of over 1 million. These new social media followers are now looking to her for direction, and she’s committed to leading in tandem with the people that have directly lived through mass incarceration, police brutality and the “violence” of poverty, underfunded education systems, and inadequate mental health and addiction programs.

“I think this is the work that I was supposed to be doing, specifically, organising with people from so many different walks of life,” says Mallory. “I have always, since I was a very young girl, worked in the community with different types of people, but they were not necessarily the leaders in terms of those setting the agenda for the organisation. This is the first time where we’re actually being led by the streets. We are being led by the temperature on the ground.”

Fuelled by weeks of consecutive global protests and rallies, the increasing temperature in the streets has ignited major discussions about policy change, defunding police departments, and combating institutional racism within corporate and public spaces. Confederate statues have toppled down and individuals and companies are being held accountable for their contribution to racism and white supremacy. Mallory is “being cautiously optimistic” about this time. She has seen people and company’s rally behind big movements before, only for excitement around the movements to settle, financial contributions to slow, and media coverage to dwindle.

Although the level of fame and celebrity she is witnessing now is new for Mallory and many of her veteran activists peers, she sees value in the recent requests from fashion magazines to put her on their covers and powerful corporations to sponsor her organising efforts. She believes these commercial opportunities are necessary leverage in this era of activism that revolves around retweets, Instagram posts, and other forms of social media to keep images of Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, and the long list of other victims of race-based acts of violence, fresh in the public’s minds.

For now, Mallory’s immediate focus is on building Until Freedom into an even more powerful and impactful grassroots organisation that will thrive even in the absence of fluctuating peaks of fame and donations. With Until Freedom, she is currently tackling two major things: lobbying for reparations that benefit descendants of enslaved African people, and defunding police departments to allocate resources to provide better mental health services, access to education, and other public services that could dramatically decrease high rates of mass incarceration, lessen police violence against Black people, and increase Black people’s quality of life.

It is in these two ways that Mallory thinks America can begin to really take accountability for the centuries of violence and suffering Black people had to endure in this country, and the continued violence and marginalisation that Black people still face today. “I think that there is no way that America will be able to gain the support and the comfortability of Black Americans until there is accountability for our murder. For state-sanctioned violence, there has to be accountability,” says Mallory.

As for what simple accountability looks like for Mallory right now, “Accountability looks like arresting four cops that killed Breonna Taylor in her home.”

Credits

Photography Deirdre Lewis

Styling Sydney Rose Thomas

Hair Latisha Chong using Bumble and bumble and Mideyah Parker at MA World Group using Oribe.

Make-up Raisa Flowers using Pat McGrath Labs.

Digital technician Paolo Santana.

Photography assistance Tatum Mangus.

Styling assistance Milton Dixon.

Hair assistance Safiya Wiltshire.

Make-up assistance Iona Moura and Ashley Brignolle.

Production Jess Mendes.

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING.

Casting assistance Alexandra Antonova.