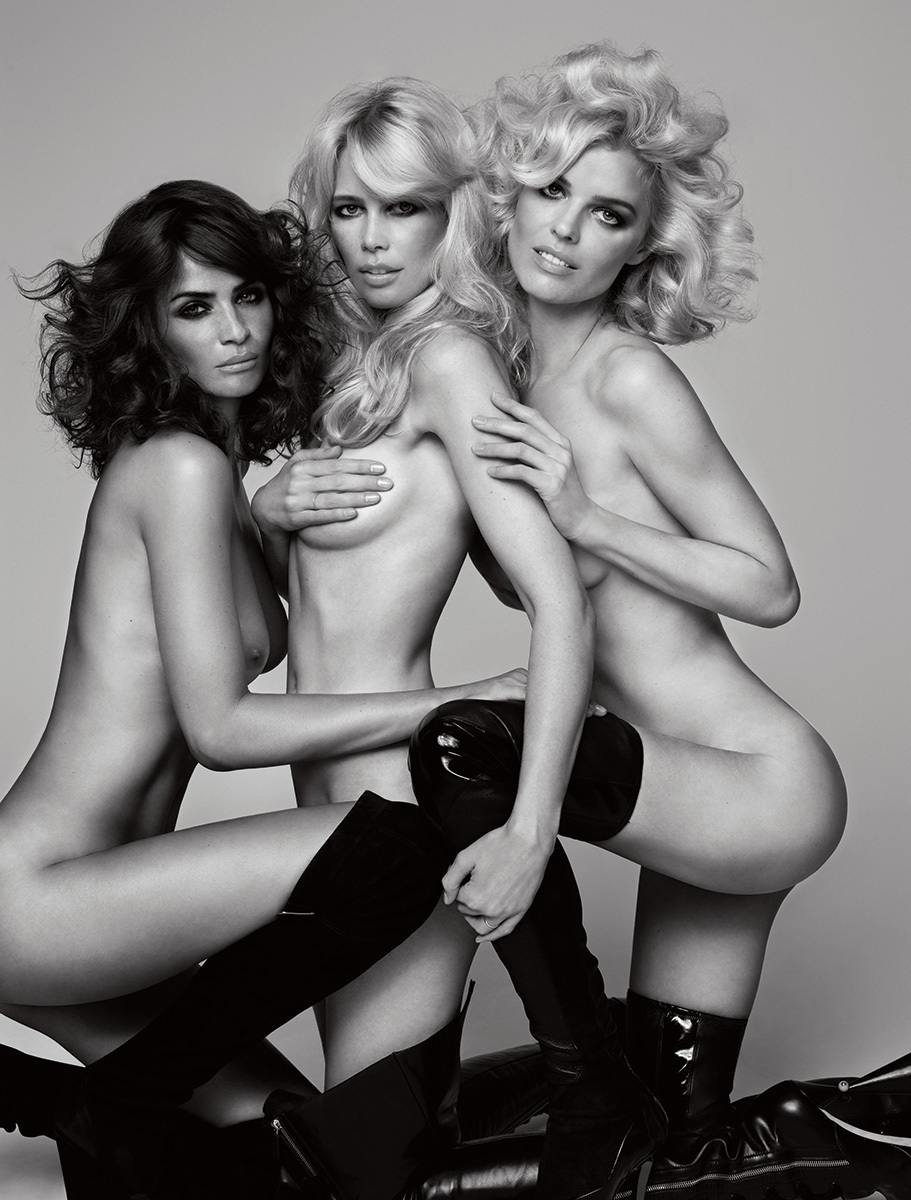

Supermodel. Like any term in currency for two decades, the fashion world is probably guilty of using it more than necessary. But on this occasion — and sitting beside Claudia, or Eva, or Helena — few descriptions would be more apt on the surface. Yet they’re prepared to go deeper, even though they’ve earned it.

Claudia Schiffer emerges from behind a curtain; this is a closed set. “We’re meant to be completely nude,” she confides, glancing over her shoulder. “Being German might help, but I’ve never had a problem with it. You can’t forget you’re in an enclosed environment where this is completely normal. Even if the assistants are thinking ‘ooh, this is sexy’ it will not show on their faces. It’s not the real world, that’s for sure.” Claudia attained a dizzying fame from the moment she began her career at 18 and it’s easy to see how she maintains it; she knows the true value of a supermodel. “We know what the photographer really wants, what a story really means, so that people look at it and instantly understand what it’s all about. To figure out how to make that work is about marketing image to other people. It’s not just about looking at clothes, it’s the extra bit that makes your emotion go. There’s no limit either: you can experiment and go as far as you can to surprise and shock people, and that’s the fun of it all. Every day can be completely different. That’s also one of the things I constantly try to figure out; the difficulty when you are a model is that every day you have to be someone completely different. You are constantly in search of who you really are.”

As a phenomenon, supermodels — and our reactions to what they do and what they stand for — have changed. In 2009, the ‘girls’ whose careers made terms like ‘supermodel’ essential are now multifaceted, modern women in charge of their bodies and careers. They have families and responsibilities. Supermodels are back in fashion in an era when conformity matters less than personality; any continued success in a competitive, evolving industry owes less to the luck of the genetic draw than appreciation for the workings of art and commerce, or an ability to feel invested in a creative process, a team effort. To think anything less of the handful of women who truly own the epithet super would be deluded, as if these women didn’t have opinions or voices of their own — as if their beauty cut off their access to any kind of intellectual life. How could it?

Helena Christensen peels off a difficult pair of boots with six-inch heels, curling up on a sofa with a cup of mint tea, clouded by milk. Spend even 60 seconds in her company and it’s obvious why creative people — actors, musicians and photographers, especially — want to bask in her glow. She has a lovely way of making others feel like they’re welcome to come along for the ride. “Being a muse is a strange responsibility, so you’d almost rather not,” laughs Helena, wrinkling her nose. “You want to be inspirational, but you don’t want to be put up on a pedestal. It’s much better to be somebody that can be touched; I’m all for the immediate and up-front confrontation. With me, things come out right away; I’m half-South American, so it’s not about that whole façade thing. Oh no. Whenever somebody does something to me, to look perfect, I want to mess it up. I always want to mess things up.” Even though she’s been successful for 20 years, Helena finds words like ‘icon’ or ‘muse’ weird to process; there’s a cognitive dissonance whenever she reads about people described in this way. “It’s not like I sat down and thought I was a muse for anyone. When you read that about yourself, you just wonder, ‘who is this person?’ and it’s like I don’t even know who they’re talking about,” she says. “I think I would rather be a muse in a personal way to somebody. I have girlfriends who inspire me so much, they become muses for me, but it’s never about beauty, it’s about what else they have.”

Eva Herzigová speaks five languages, reads voraciously, and is radiant in person. Life’s just not fair, is it? Within five minutes of meeting her, she recommends watching the Czech film Daisies, describing it as post-feminist despite its 60s origins. In an unfussy blouse and jeans, Eva seems appreciably stronger as a person than her 90s image — wild woman in a Wonderbra — suggested to outsiders. “It’s a closed box. It totally seems like someone else’s life or another lifetime; it doesn’t seem like she was even me! My life now feels like it’s in the third act,” she explains. Eva’s memory of the times doesn’t include seeing GOODBYE EQUAL RIGHTS scrawled across the decade’s most controversial billboard advertisement. “I never knew feminists campaigned against Wonderbra billboards,” she claims today. ‘Hello, Boys’ was, after all, Mae West’s trademark greeting, and she wasn’t exactly known for suffering masculine fools. “The ad campaign had a liberating effect on women; it changed their consciousnesses. What people remember 15 years later was not the product itself, but the empowering effect of the ad campaign. It was revolutionary to suggest that women were in control of this; it was very smart. That’s why people still think it happened yesterday.” In the late 1980s, when Eva began working as a model, her native Czechoslovakia was still under Communist control.

To work abroad, Eva held a special artist’s travel permit to leave the country. “Paris wasn’t far but it was far enough; we didn’t have such freedom to travel back then. I could go back and forth, but I had to give the government 40 per cent of everything I made in exchange for that little stamp in the passport. Technically, I was with an artists’ agency run by the government and that was their commission.” In 1989, six weeks after she received her golden ticket, Czech dissidents led by a playwright, Vaclav Havel, fomented the Velvet Revolution. This led to the overthrow of the Communists, hastening the fall of the Iron Curtain and the end of the cold war. Eva watched it all unfold on television in Paris. “For me, it was like ‘gee, I can get out of this country. Go!’ I left in September and then in October there was a revolution. Everything changed — not immediately — but I did leave while it was still a Communist country. It was perfect timing. Suddenly Havel arrived. I realized things were possible, change was possible.”

You’d have to be pretty blinkered to ignore the world when you’re always on the move; travel forces most people to reconsider their perspectives. Helena Christensen was Miss Denmark at 18 and a famous model by the age of 20, yet had the confidence to call herself a photographer at 17. The portfolio she most wanted to expand had her behind the aperture, not in front of the camera. “I started modeling so I could work on my photography while I was doing it,” says Helena in a wry that-was-the-plan voice.

The logistics behind getting these three superwomen together for a morning are awesome in the original sense of the word; they haven’t been shot as a trio for over a decade. Helena jets into London only to leave later today for Copenhagen; Eva’s two-year old is convalescing with a broken leg at home. Both Eva and Claudia live in west London; Claudia’s off to Marbella with her husband, son, and daughter this afternoon. “The difference between now and when I didn’t have a family is that before, you just went from one job to another and you’d become blasé almost, and arrogant to the point where you’re saying things like ‘oh, I’ve got a shoot with Steven Meisel for Vogue today’ like it’s this everyday, of-course thing, like what else could it be?” Claudia chuckles at her younger self. “Now that I’ve taken a little break to have kids I’ve looked back and I just think ‘Jesus, that was really amazing!'”

“When I do my shoot I look at it completely differently, like I appreciate every moment of it and think the longevity is amazing. It’s a different attitude, also, because I can do what I want and turn down the things I don’t. That security is quite nice to have, but it takes a while to realize.” Planes, trains and automobiles are still all in a day’s work, but the collaboration and technology of working in 2009 excites Schiffer. “Creatively, everybody can be so much more involved and on-point on a digital shoot. That makes it so much more fun: before, the photographer pulled all the strings, filtering everything through what he sees. Now everyone can see it and give their opinion, working together. You can also go much further, because you feel comfortable that the thing you’re seeing is something you like. You spend much less time.” If, like Claudia, you’re a pragmatist, this means there’s more time to work on a wider variety of projects and meet up-and-coming talent on editorial shoots. “A great photographer is the one that gives you confidence, that wants to have fun within the moment, doesn’t stop you or give you boundaries. It’s about flow and chemistry; you just go together, like a wave. Some photographers don’t work that way; they stop you because they are extremely critical and they’re only looking for that one moment of perfection and that’s actually bad because it stops your flow.”

“The thing is, not a lot of people are comfortable with having their photo taken,” Helena Christensen reasons from a point of view at ease on both sides of the camera. “Making fashion stories is the creation of a surreality, a third dimension or a fairy tale, or a different world. It’s an altered reality somehow, where everything is exaggerated, like movies or anything you create because it’s also everyone else creating around you. You’re just in there being done-to. Finally, when the camera clicks you’re on your own, but everything on you and done to you isn’t really you.”

These are still legitimate concerns to raise in a world where every teenager aspires to a dressed-to-kill career, and not just on the catwalk. The non-stop broadcasting of model contests and makeover programs, the mainstreaming of the facts and fictions of famous fashionistas — all these enticements exert a forceful pull towards every facet of the fashion industry. “Generally, there’s a very quick turnaround for models in the industry nowadays, even quicker than it was in the 90s,” reasons Claudia. “For me there was a lot of luck; I went out dancing with friends in Dusseldorf one night and an agent was there. If I’d had to enter a Top Model contest you’d never have gotten me through the door. My parents would have been horrified by the idea. With fashion, the one thing to consider is that you have to make a choice in your life. Is this really what you want to do, or a fun hobby? What are your goals in doing this? Is it to become famous? Because then you can forget it. Is it to make money? Okay, that’s one career path and you choose accordingly. If it’s like what I did, it wasn’t about the money or fame, it was just about wanting to be ‘best-at’ what I did, which was being the best you can be as a model, as an inspiration for designers and photographers and the best at being able to read what they want in return.”

With all the talk of the struggle to maintain an identity in a quickly-changing environment, these women feel a sense of accomplishment at continuing to work at the highest level in a challenging and involved job; the environment of a shoot is simultaneously the eye of the hurricane and where all the action is. Like Claudia and Helena, Eva Herzigová enjoys it here; she seems able to look at the span of her life and think ‘what the Hell just happened here?’ “I do wonder,” she admits. “When you start at 16 or 17, you adapt so fast. There’s a period of worrying that you’ve gotten sucked in and wondering if this is what you really wanted. Now I can’t even imagine taking a break. Even when I was pregnant, I worked to nearly the end of my term and came straight back. I tried many times to take breaks before, but three days later I would decide I missed working too much!”

Credits

Text Susan Corrigan

Photography Kayt Jones

Styling Pippa Vosper

The Flesh and Blood Issue, no. 304, Winter 2009