Over three decades since its release in 1983, “Thriller” is still one of the most iconic music videos ever made. A B-movie inspired zombie fantasy starring the world’s most famous musician, a former Playboy model, and a cast of ghouls with moves like we’d never seen, the mini-movie was not only a hit with Jackson fans — selling over nine million copies — it was also a critical success. Directed by Los Angeles filmmaker John Landis, “Thriller” proved that music videos could go above and beyond their usual call of duty — selling records — and become cultural phenomena. It was the first music video to be acquired by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically or aesthetically” important.

This September, the 14-minute masterpiece will premiere in 3D at the Venice Film Festival. It will be the first time the film has screened since the 1980s, playing in an hour-long program alongside a 45-minute documentary called The Making of Thriller.

Why has it taken so long for “Thriller” to return to the screen? Landis battled with the Jackson Estate for five years over the music video’s rights, finally resolving the lawsuit in 2012 and winning a settlement of $2.3 million, half the film’s rights, and access to the original negatives.

“Since I had new access to the negatives, I had the chance to polish it and made it gorgeous,” Landis tells me over the phone from his home in Los Angeles. “It looks like shit on YouTube.”

The idea for the “Thriller” video was born in 1982, a full year after the release of the Thriller album. The record was already number one on the Billboard chart and had become the bestselling album of all time. But Jackson saw Landis’s horror film An American Werewolf In London (1981) , loved it, and asked the director to collaborate.

“He called to say he was a fan of my film,” says Landis. “He wanted to make a rock video where he turned into a monster and he felt he had the best song to do it with, ‘Thriller.'”

Landis was sceptical when he first met Jackson in Los Angeles. “I thought, ‘I don’t know, because music videos are essentially commercials to sell records,'” he remembers, but then he changed his mind. “I decided to do ‘Thriller’ because it was an opportunity to do a proper musical number.”

Landis wanted to make the project more than just another music video. He proposed to Jackson that they turn it into a short film and Jackson agreed; it was in line with his own approach — which was setting a near-impossible standard of perfection. (Jackson later told MTV of making the video: “It has to be, you know, my soul.”) “He wanted it not just to be great, but the best,” says Landis. “He wanted to be the best at everything he did.”

According to Landis, most music videos cost roughly $30,000 to make in the 1980s, but “Thriller” ended up costing $500,000 because, among other factors, it had the biggest makeup call since The Wizard of Oz. Rick Baker, the Academy Award-winning makeup artist famed for crafting Gremlins, was brought in for the elaborate prosthetic transformation of Jackson and the cast of zombies.

Landis refers to “Thriller” as a “vanity video.” It was Jackson’s personal fantasy to turn into a werewolf simply because he thought it was cool, the director underlines. “Nobody was interested in making it other than Michael,” he says. “He very much wanted to turn into a monster.”

Landis and Jackson asked Walter Yetnikoff, then president of CBS Records, to finance the project, but when Landis got on the phone with Yetnikoff, Landis says he heard nothing but expletives. He recalls Yetnikoff saying, “Who the fuck do you think you are?” and “We are not paying for this!” “The record company felt ‘Thriller’ had peaked and they were onto what’s next,” he says. “Why spend any money on it?”

So, to fund the music video, Landis and Jackson shot a 45-minute documentary, The Making of Thriller, and sold it together with “Thriller” as a one-hour program to two TV stations: Showtime, which got the first five-day run, and MTV, which was then able to play the program for another week.

The double feature was then sent to hundreds of TV stations worldwide and helped triple the album’s sales. Roughly 3 million “Thriller” VHS tapes were sold in America and 10 million around the globe. “‘Thriller’ had this huge impact that nobody but Michael Jackson thought would happen,” says Landis. “Honestly, I was totally unprepared for that kind of success. It was unprecedented and completely unexpected.”

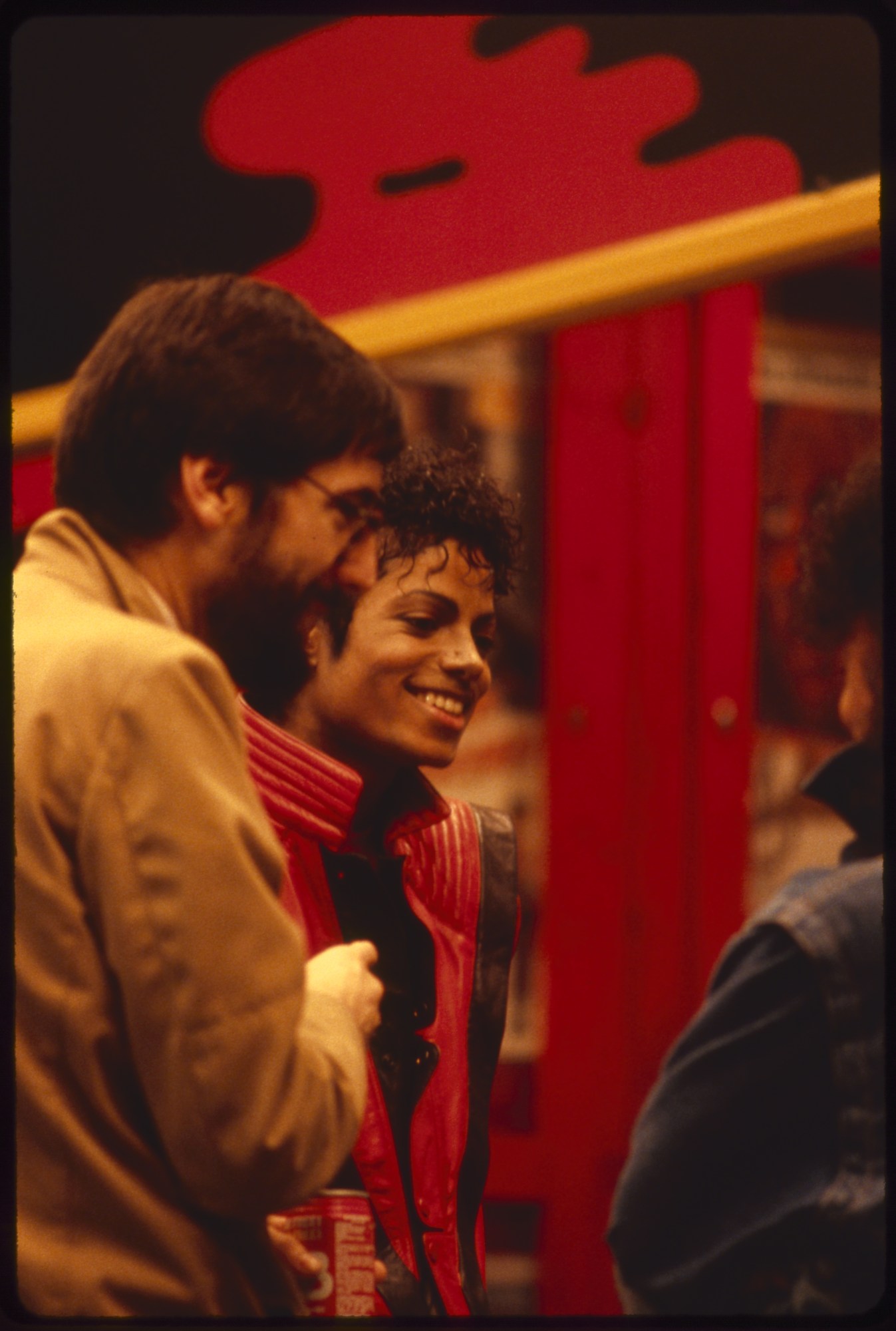

The music video itself was shot over five days in October 1983 in a D.I.Y. graveyard set up at a Downtown Los Angeles meatpacking plant. The neighborhood was then a gang area, so there was a heavy police presence, Landis remembers.

Jackson’s fans were also never far away. “Wherever he showed up, there would instantly be thousands of people screaming hysterically,” says Landis. “There were four or five thousand people hanging out outside the set just to get a glimpse of Michael.”

Jackson, who was 25, had his friends pop by too: Marlon Brando, Fred Astaire, and Gene Kelly. When Elizabeth Taylor called, Landis had to tell her Jackson was too busy to talk. “I’d say, ‘Hi Elizabeth, I’m very sorry this is John Landis, but we’re shooting, so can Michael call you back in a few hours?'” he recalls. “That was unusual.”

The most surreal moment of the “Thriller” shoot, though, was at 3:30 a.m. one day, when Jackson, who was in his Winnebago by the railroad tracks, asked Landis to come visit him. “As I’m entering, I hear Michael say, ‘John, do you know Mrs. Onassis?'” Landis says. “It was so bizarre! If you asked me, ‘Who did you expect to see?’ I would not have said ‘Jackie Kennedy.'”

While Onassis didn’t appear in the behind-the-scenes footage, the “Thriller” documentary has great clips of Jackson in his prime. There is footage of his performance at the Motown Records 25th anniversary, which shot him into superstardom, as well as old film reels of the singer dancing as a kid, which Landis got from Katherine Jackson’s closet.

The film is a testament to Jackson during his best years. And if Jackson were still alive, Landis says he knows what he would think of “Thriller” playing on the big screen at the Venice Film Festival. “Michael would have been beside himself with joy,” he says. “People can finally enjoy the film as it’s supposed to be experienced.”