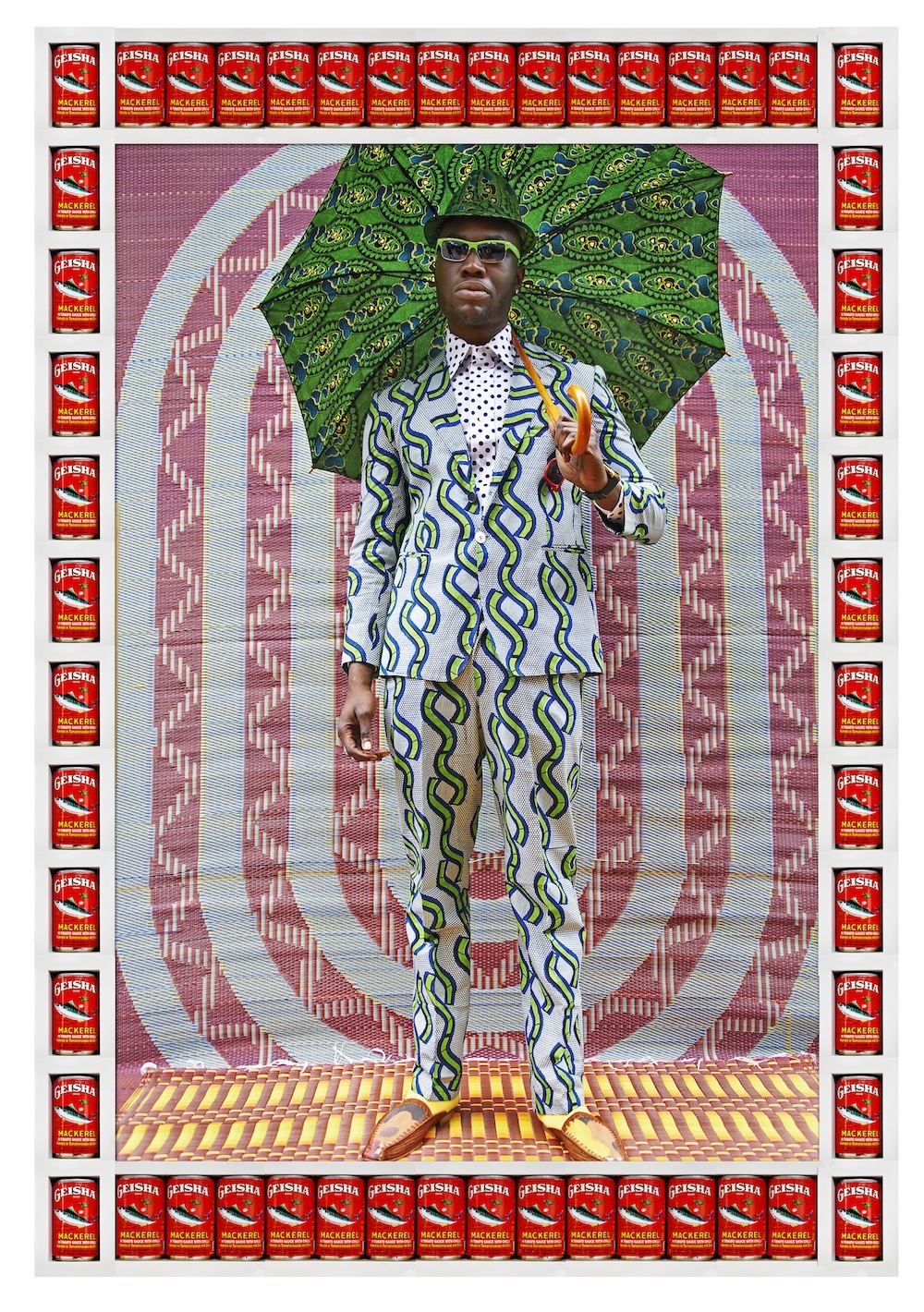

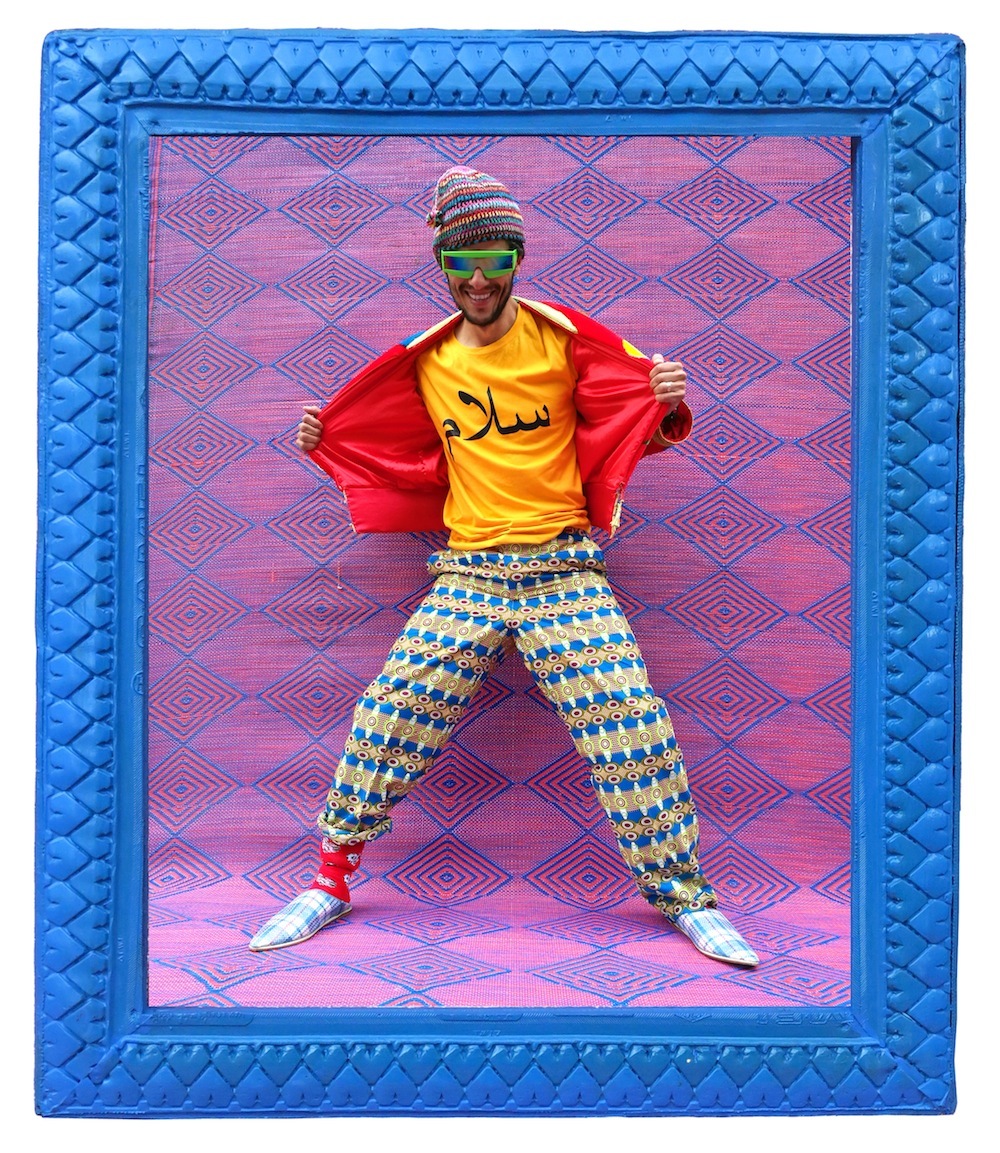

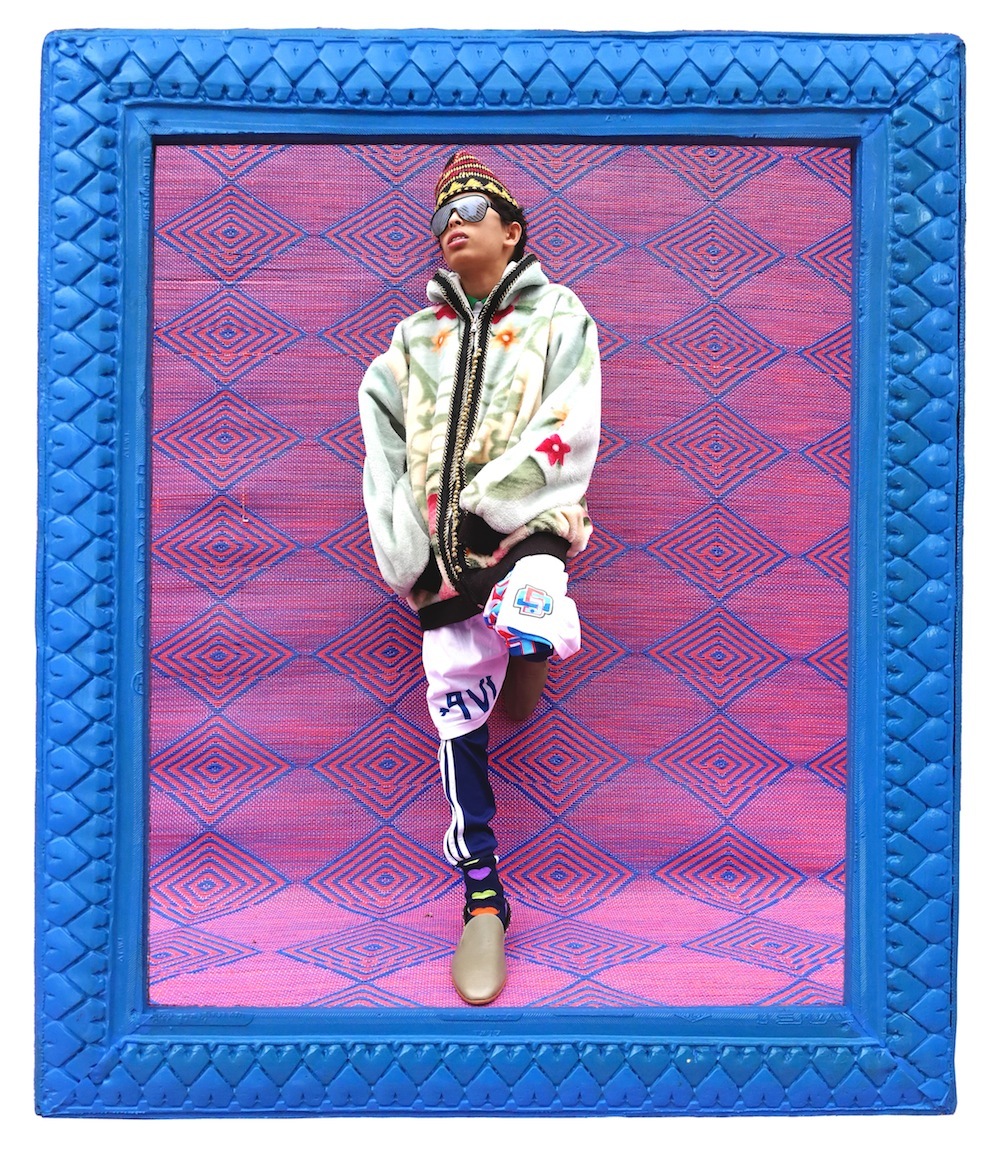

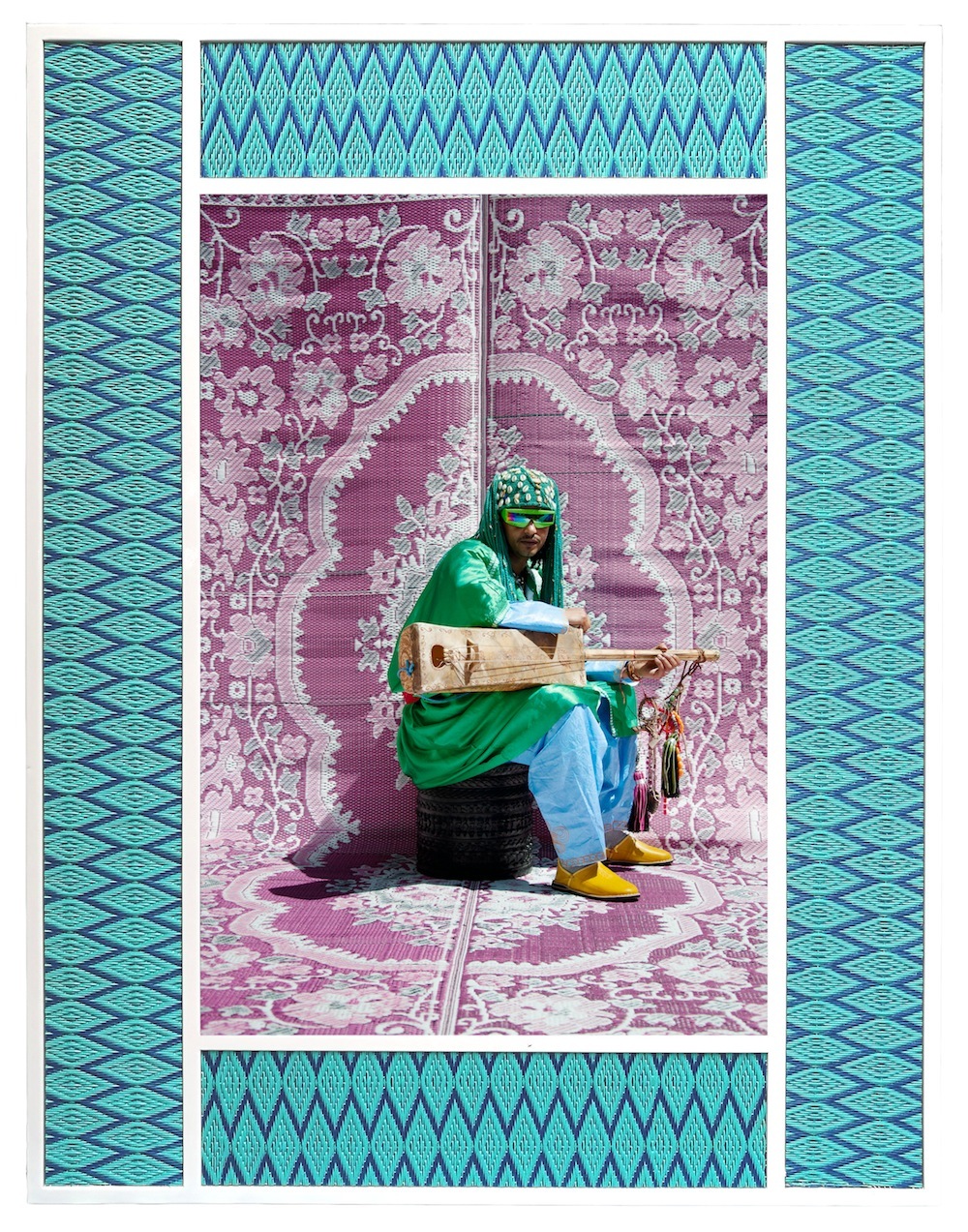

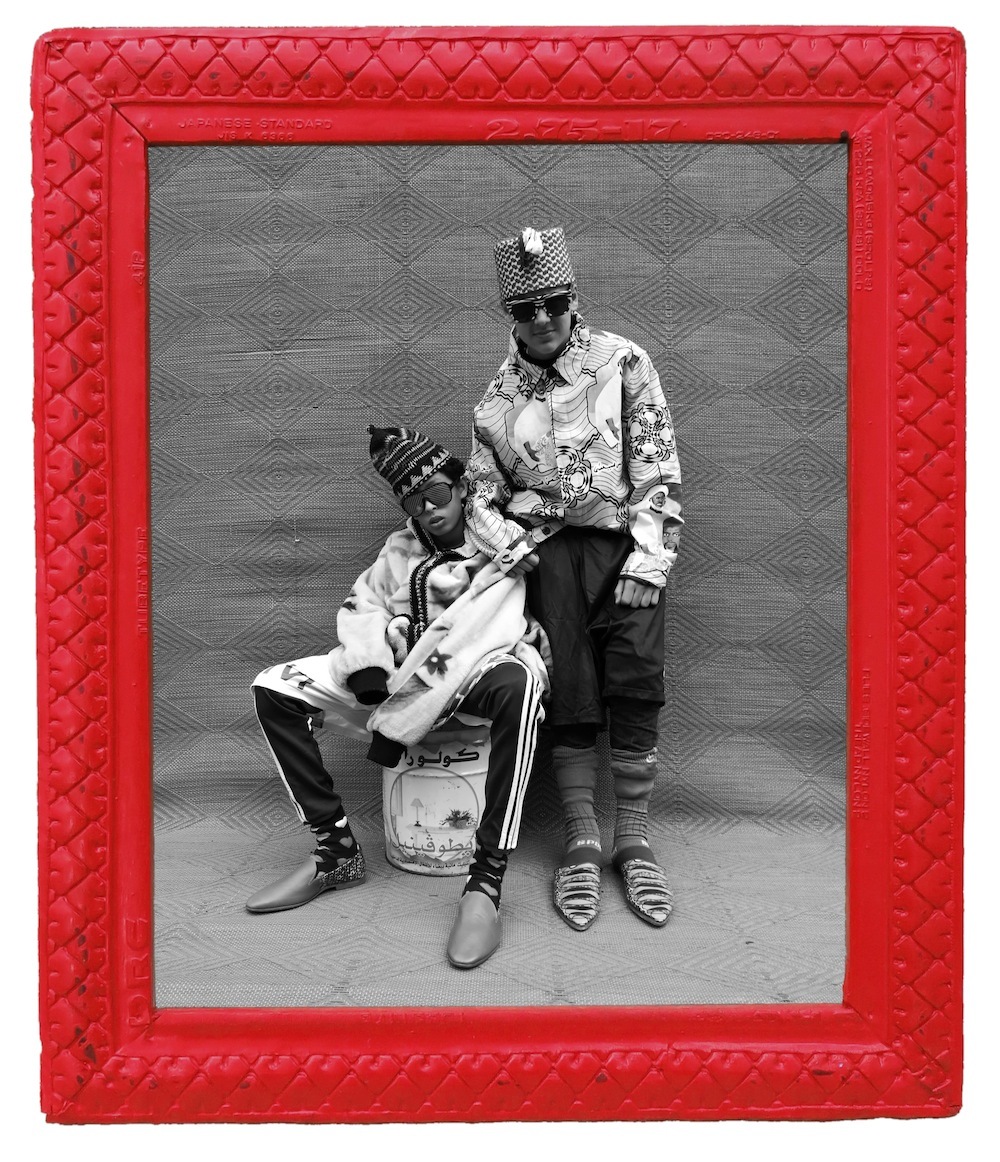

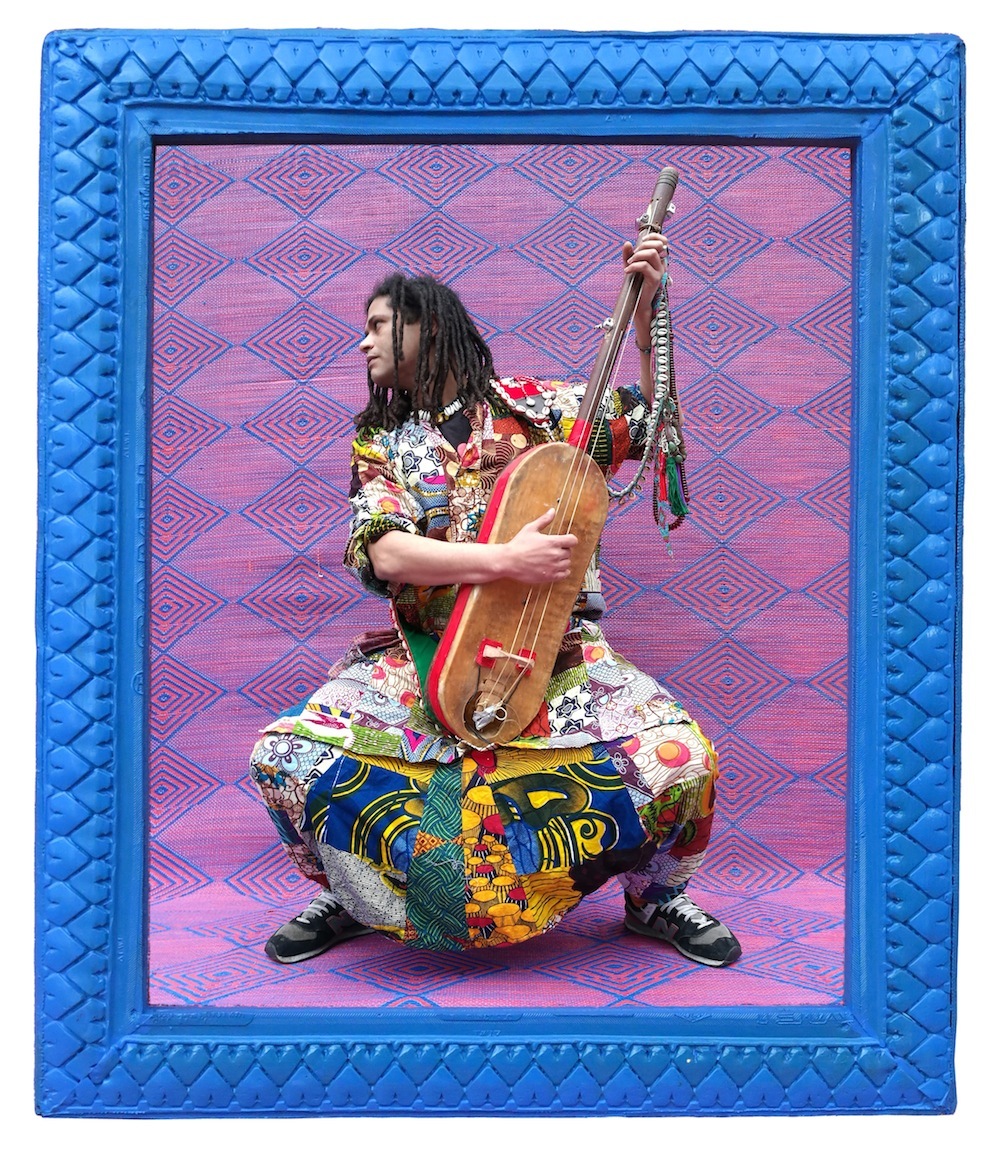

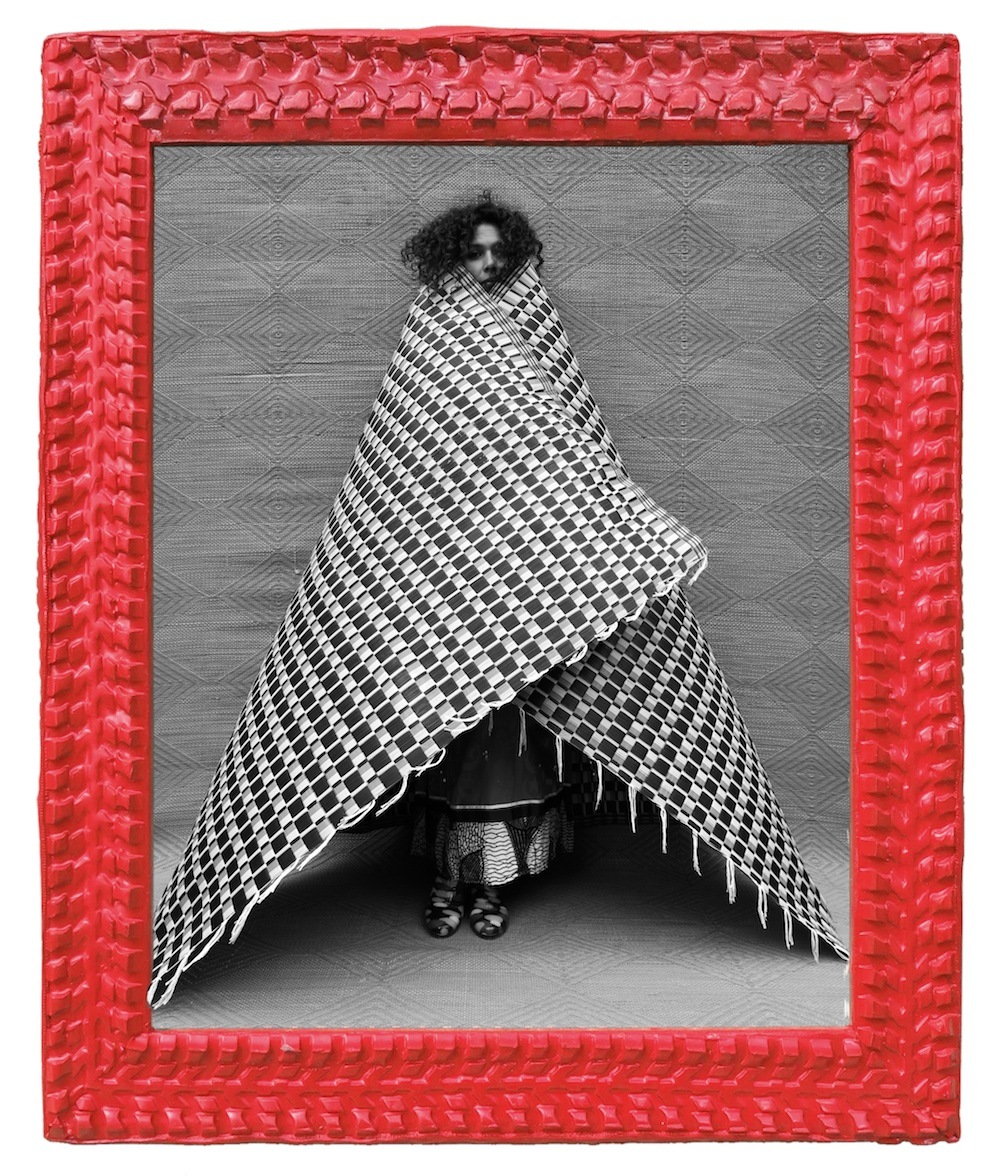

Photographer Hassan Hajjaj captures his subjects with energy and confidence, in both individual and sartorial terms. His images meld fashion photography and portraiture imbued with African heritage. Moroccan-born, Hajjaj lives between London and Marrakesh, and his aesthetic expresses this mutual influence. He features his direct entourage on the flip side of the camera, and his friends and family are creative types all. He shot his latest series over one day-long session in April, animated with food and music. (“It was a bit of a party!” Hajjaj admits.) Pulling from a rack of clothes, each subject’s look was enhanced with Hassan’s designs, plus bright socks, hats, sunglasses, and other accessories bought cheaply at the local markets. The frames of his photographs are just as essential to his work, bringing layered dimensionality and an artisan’s touch. Woven plastic mats, stacks of empty canned goods, and stretched and taut painted tires outline and texturize the portraits.

For his first showcase at Colette, Stylin’, Hajjaj also created ceramic jars, bright his’n’her sneakers with Reebok (available widely in September), and reversible silk jackets with bold iconography of African musicians. Hajjaj feels much more welcome in France now than in the past: “the relationship between the Moroccans and the French is this kind of Tom and Jerry thing,” he notes of the countries’ colonial entanglement. Beyond Colette, he has a solo show in Memphis at the Brooks Museum, is part of a group show curated by Duro Olowu at Camden Arts Center in London, and has three pieces in Made You Look: Dandyism and Black Masculinity at The Photographers’ Gallery in London. Warm and gregarious — and lively despite fasting for Ramadan — the photographer discussed remixing traditional garb, the in-betweenness of juggling two cultures, and his need to be connected to his photographic subjects.

Between your photos and clothing designs and ceramic jars, you have a diverse creative output. What came first?

Like the chicken or the egg? Well, I came from a non-artist background. Luckily, I grew up with friends who were photographers, musicians. Photography was a hobby. While I was taking pictures for fun in the ’80s, I had a small boutique [in Covent Garden]. I put DJs on, bands; I would ornament the space and decorate it for the night. And I worked as an assistant stylist on music videos. When I started doing photography, all that other stuff—which I call my schooling, without realizing it then—had an influence.

I had a fashion store and label called R.A.P, from 1984. I’m not a technical designer: I’ll find a fabric and make a sketch and have it sewn: I’m coming from that kind of element. I was doing that for my store. With my friend Amine Bendriouich, who’s a fashion designer—and a hidden gem—we’ve done an edition of 12 bomber jackets using African fabrics for Colette, and we’ve done fashion week in Tunisia. With Reebok, a friend who’s a designer introduced me to them, and there will be an autumn edition.

You live between London and Marrakech—how do you balance the two? How did the style in each place rub off on you?

I was born in Morocco, and left at the age of 13. Since I had my daughter in 1993, I go back and spend six months there, six months in London. I’m a misfit: coming to London, I’m not English, and in Marrakesh, I’m a Moroccan who lives outside the country. So I’ve had to find my place of comfort.

In Morocco, there’s a lot of tradition in what we wear. In London, it’s international. When I take pictures in Morocco, I’m using traditional stuff, but making it look hip. How you do that is through the person. When you see a man in a gown, it’s a ‘dress,’ according to a Western person. But we don’t see it as a dress! So how do you capture that? I apply the Western eye to the African tradition: I sit in the middle, and try to provide a keyhole into my culture. That’s why I use Vuitton and stuff, with the traditional. Because I find it easier to communicate to people from the West. A brand is a comfort space; it’s not threatening anymore. It’s not Muslim or Arab: it’s fashion.

Do you feel like you need to integrate brand recognition for people to soak in the traditional counterpart?

No, not at all. It happened naturally, but I’m glad it happened because we live in a branded world. It’s everywhere, and it’s a reflection of that.

Cultures have a style and tradition. People don’t see that, they just see an African fabric. If you look deeper, there’s a lot going on. It’s actually very couture: because people go out and buy the fabric, take it to somewhere local to get it made. Can’t get more couture than that.

I have lots of friends in London from different parts of the world. And I said to them: Do you have any traditional stuff in your cupboard? Everybody said yes. Something they wore to a wedding, or something their mum gave them. So I asked friends if they could pose with something traditional. A sari, if you look deeper into, is about the way you wear it, like how much skin you show. I want the younger generation to still have roots with the tradition. I want to see that trend.

Which photographers do you admire, or that have influenced your universe?

I didn’t study photography but I’ve always flicked through magazines and books. There’s Malick Sidibé. Dave LaChapelle represents fashion in a different way. Nick Knight. Richard Gordon. William Klein—I love his neon light film.

Do you always do portraits?

Mostly. I use photography to express myself. If you said, shoot jewelry, you’d be asking the wrong person. I’m not doing photography as a promise to anybody. On a job, you can’t make mistakes. I can afford to make mistakes. If it’s mine, I don’t have to deliver ten pages, or whatever. Maybe I do four pages I’m happy with: simple as that. It’s about that connection with people; that makes the difference for me. I’m trying to capture energy more than beauty.

Stylin’ by Hassan Hajjaj: exhibition on view at Colette in Paris through August 27.

Credits

Text Sarah Moroz

Photography Hassan Hajjaj