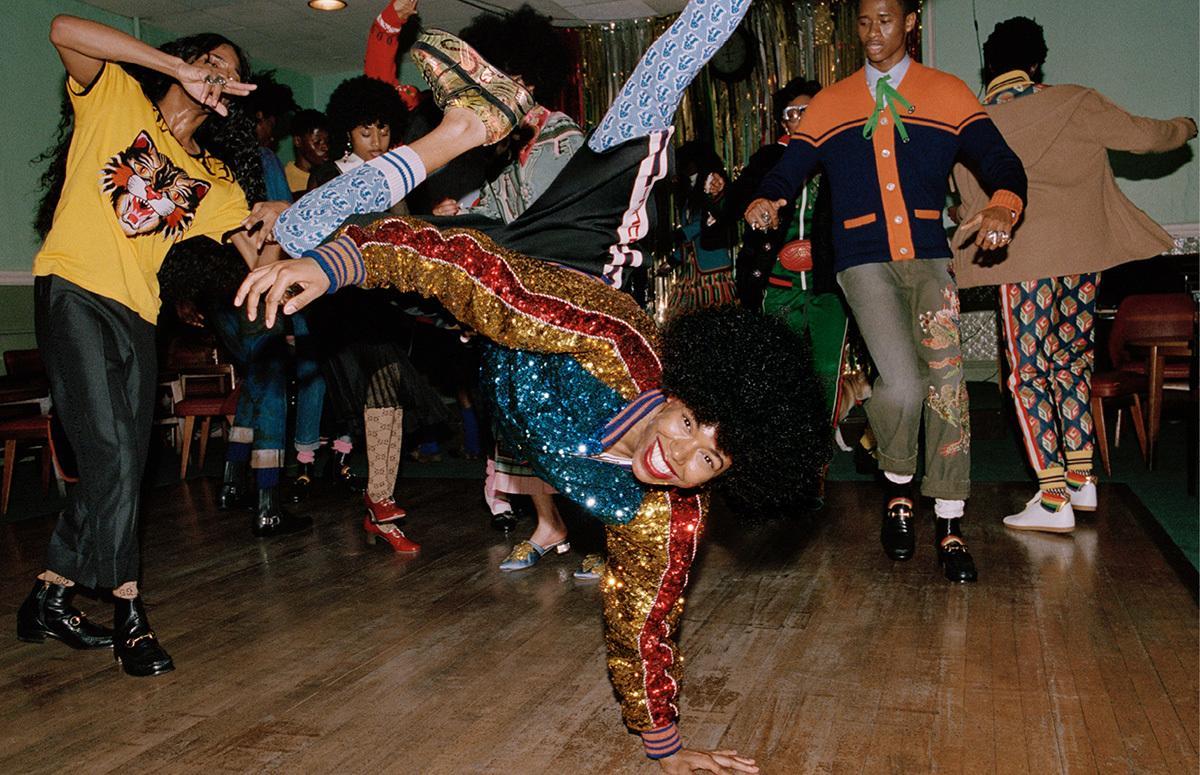

For its pre-fall campaign this year, Gucci paid homage to the Northern Soul scene of 1960s Britain. The joyful imagery, shot by Glen Luchford, was filled with mid-action scenes of black people getting down and funky and just, well, being black. In keeping with this spirit, there were plenty of models rocking ‘fros, some short, some large. They conveyed a vintage hipness that so many brands — from Gucci to Prada— have been trying to capture lately. Gucci’s campaign provoked the ire of many critical writers. The problem was this: black styles such as afros that have faced discrimination in the past are now being used to sell clothes. Which raises the question, how did this hairstyle go from being a symbol of political radicalism to representing luxury?”

The voluminous hairstyle — a glorious, untamed display of blackness — has been misunderstood for centuries. When captured slaves were first brought to America during the 15th century, their hair was forcefully shaved off in an effort to strip them of their sense of cultural identity. Even after gaining emancipation black people steered away from letting their hair grow out as biology intended. When Madame C.J. Walker patented the hot comb during the Reconstruction Era, scores of black women took to turning their kink and curls into straight hair — often hoping the metamorphosis would help them assimilate into white society. It was not until the Civil Rights Movement that the afro became “cool.” But even then, the hairstyle’s popularity was less about being “attractive” and more about being “disruptive.” Rocked by the Black Panthers and iconic activists like Angela Davis, Nina Simone, and Nikki Giovanni, a single hairstyle came to represent the never-ending fight against racism.

“Our hair was a physical manifestation of our rebellion,” Lori L. Tharps, coauthor of Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America, tells i-D. “The right to wear our hair the way it grows out of our heads. Saying to the establishment: ‘Accept us and appreciate us for who we are.’ Stop expecting us to assimilate or subjugate ourselves to make you comfortable.”

Afros have frequently been categorized as “unprofessional” or “inappropriate.” In her book about the beauty industry’s relationship with African-American women, Style and Status, Susannah Walker relays the story of Annabelle Baker who, in 1943, was told by the Dean of Women at Hampton Art Institute that it was disrespectful for her to wear an afro while representing the school at a conference. “They told me that I should be ashamed to wear my hair in its natural state,” Baker is quoted as saying.

And the pressure for black people to “tame” their hair existed for men as much as it did for women. In the 60s, it was common for men to “conk” their hair (make it straight but wavy with a homemade chemical relaxer of lye, eggs, and potatoes). Malcolm X criticized conking in The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1964) and associated the painful process with internalized self-hate. “But then my head caught fire,” he recounted. “I gritted my teeth and tried to pull the sides of the kitchen table together. The comb felt as if it was raking my skin off. My eyes watered, my nose was running. I couldn’t stand it…”

Black people have had to spend a lot of time, and endure serious pain, to get rid of their afros.

The Black Panther Party made it their mission to eliminate this burden. They concerned themselves with carving out spaces for black bodies and generating appreciation and love for those bodies. Afros were the party’s middle finger to white beauty aesthetics. Both men and women turned away from the plethora of methods cooked up to transform black hair into new textures and grew their hair out to eye-catching proportions.

“This brother here, myself, and all of us were born with our hair like this, and we just wear it like this because it’s natural,” Kathleen Cleaver, a prominent member of the Black Panther Party (who was the target of many police investigations), said during a 1968 rally. “The reason for it, you might say, is like a new awareness among black people that their own natural physical appearance is beautiful and is pleasing to them.”

It’d be impossible to talk about the history of ‘fros without mentioning Angela Davis. An activist and professor, Davis was put on trial for conspiracy in 1971 after four black men performed an armed takeover of a Marin County courtroom — simply because of her connections with the gunmen. When Davis fled California, she was added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List by J. Edgar Hoover. There Davis was on a wanted poster, her afro taking up more of the picture than her face. For many white Americans, it was their first time coming across radical black politics and an afro so majestically large. “I was portrayed as a conspiratorial and monstrous Communist (that is, anti-American) whose unruly natural hairdo symbolized black militancy (that is, anti-whiteness),” Davis reflects in Afro Images: Politics, Fashion, and Nostalgia (1994). Despite the fact that Davis was acquitted by a federal judge of all charges, for some, afros and violent anti-whiteness became forever synonymous.

Five decades since Angela Davis’s arrest and afros still possess an air of radicalism. No matter a person of color’s place in society — whether it’s Solange or a teenager in middle America — blacks frequently have to defend themselves when they decide to grow an afro. In 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio was cornered into voicing his support for his son’s signature afro in the middle of an interview with hip-hop radio station Hot 97. The host asked de Blasio if his son would shave his afro if an important internship or job was on the line. “That is not happening,” de Blasio quickly responded. “I want to categorically deny that Dante will ever cut his hair. He is adamant.” The mere question asserted that a person of color should be not only willing, but also accepting, of changing their hair to make someone else happy. That in order for black people to create opportunities for themselves, they have to stick to certain hairstyles.

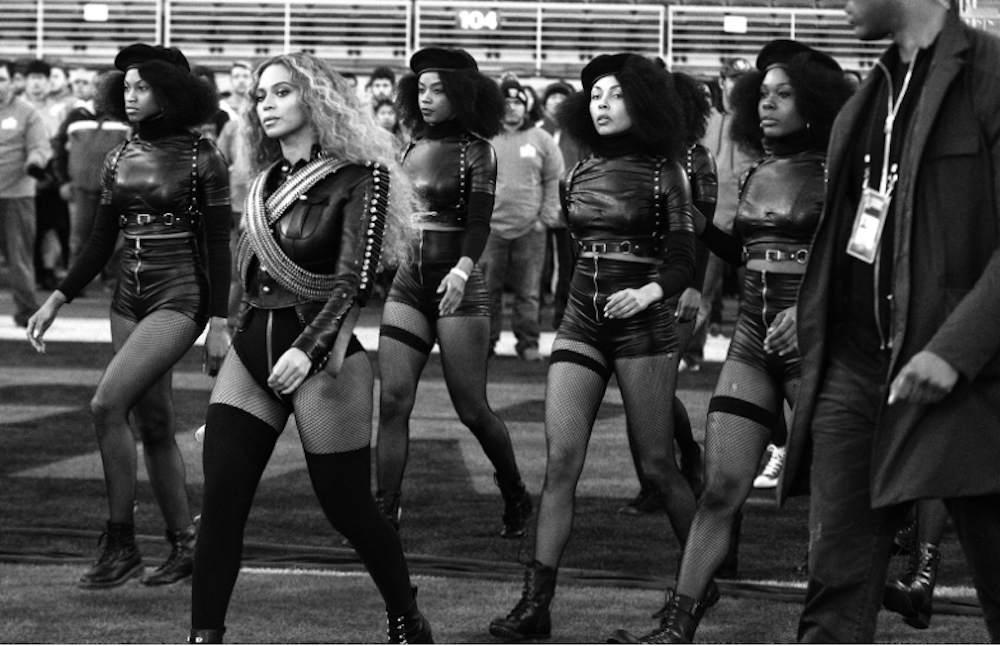

And who can forget the outrage Beyoncé elicited from conservative outlets after her 2016 Super Bowl Halftime Show performance? The backlash was in response to the singer dressing her dancers in Black Panther-inspired berets and afros for the black pride anthem “Formation.” The Miami Fraternal Order went so far as to call Beyoncé “anti-police” because of the performance, saying, “The fact that Beyoncé used this year’s Super Bowl to divide Americans by promoting the Black Panthers and her anti-police message shows how she does not support law enforcement,” and called for police officers to boycott providing security for her upcoming concerts. Here it was again: conservative white media shifting a moment of unrestrained black joy and beauty into an attack on whiteness.

Is it not possible for an afro to just be an afro?

Recently, thanks to celebrities like Solange, Naomi Campbell, and Elle Varner, afros have made a comeback. This time, Professor Tharps says, the “Back to Natural” movement is tied to appreciating black hair for its uniqueness and beauty, and not for advancing a political cause. “You go to the pharmacy and there’s a ton of nice smelling, expensive products for natural hair now,” she says. “It helps make natural hair be looked at as luxurious.

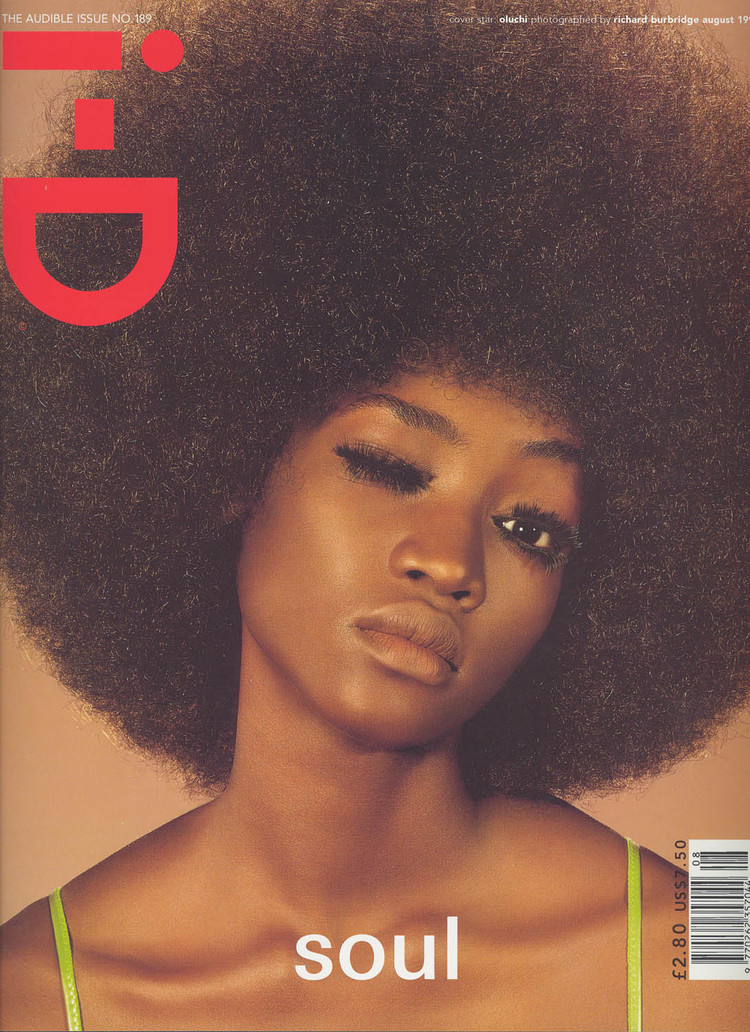

Fashion has joined in on the afro wave, too. For its fall/winter 15 show, Prada generated buzz when it cast Lineisy Montero, with her short little afro, in her first ever runway show. She later appeared on the cover of i-D’s The New Luxury issue. Even today’s superstar black actresses, like Viola Davis and Lupita Nyong’o, have embraced short ‘fros. One of the most pivotal moments yet for the natural hair movement occurred when Lupita Nyong’o appeared on the cover of Vogue‘s August 2015 issue. There Nyong’o stood, wearing a medium-sized afro and a Valentino haute couture dress. This was part of the Black Panthers’ fight for the advancement of black people in America — a person-of-color being celebrated as one of the most beautiful people in the world.

Credits

Text André-Naquian Wheeler

Image Richard Burbridge [The Audible Issue Issue, No. 189, 1995]