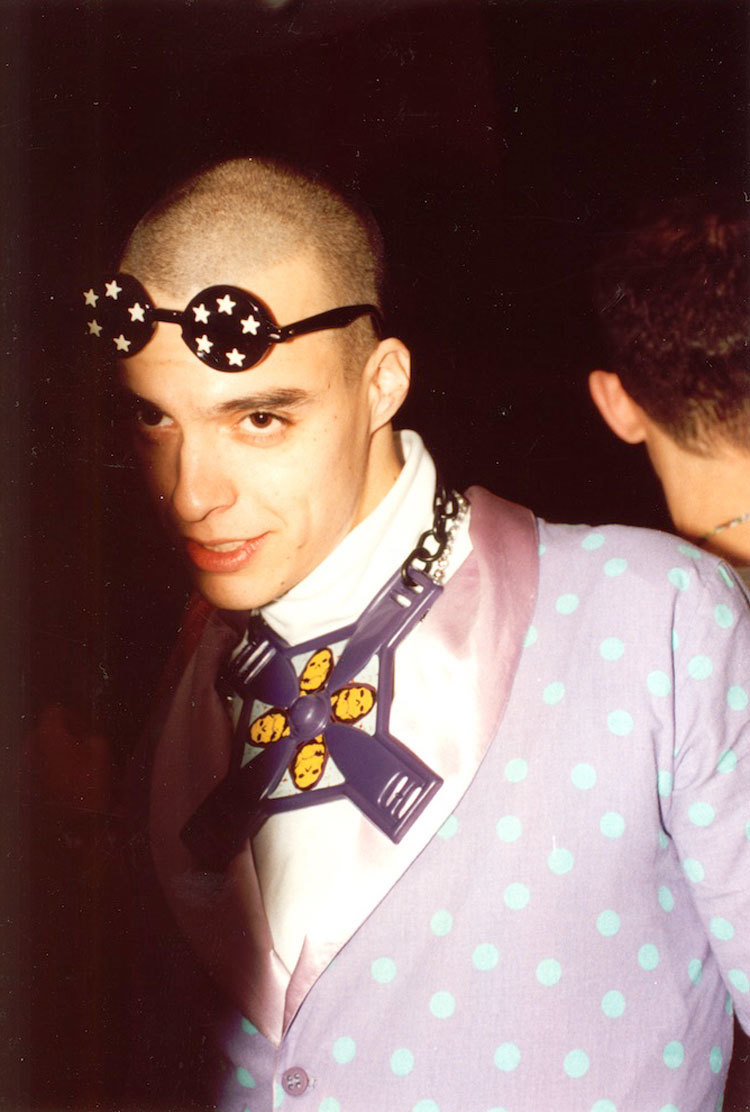

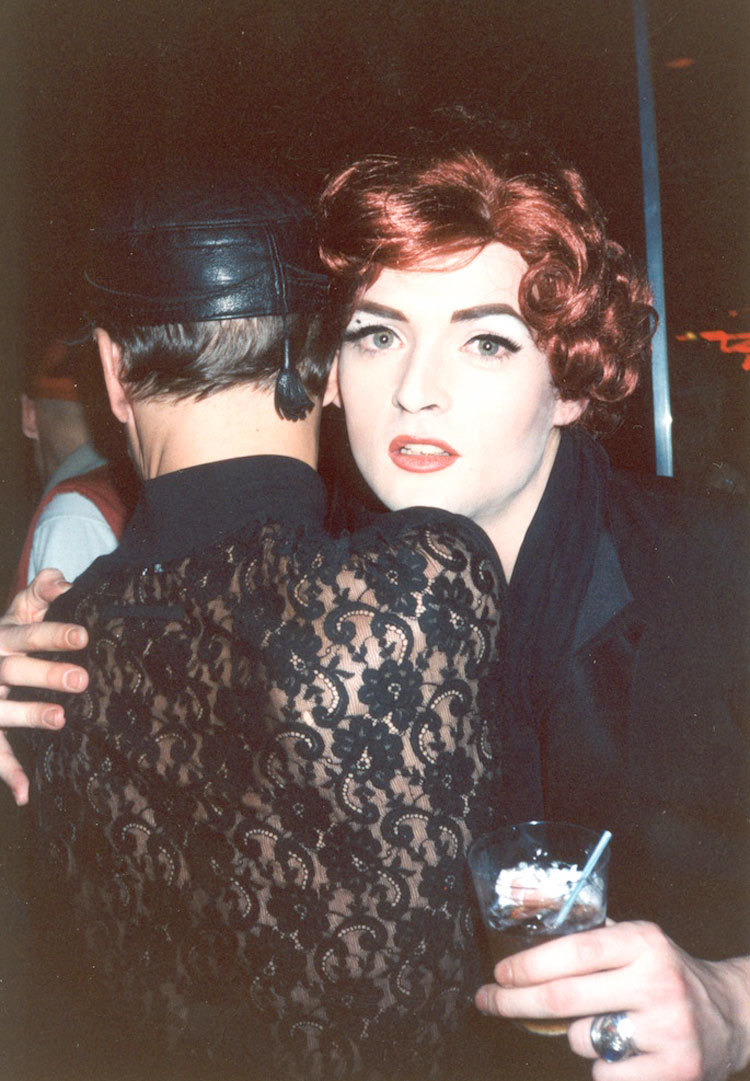

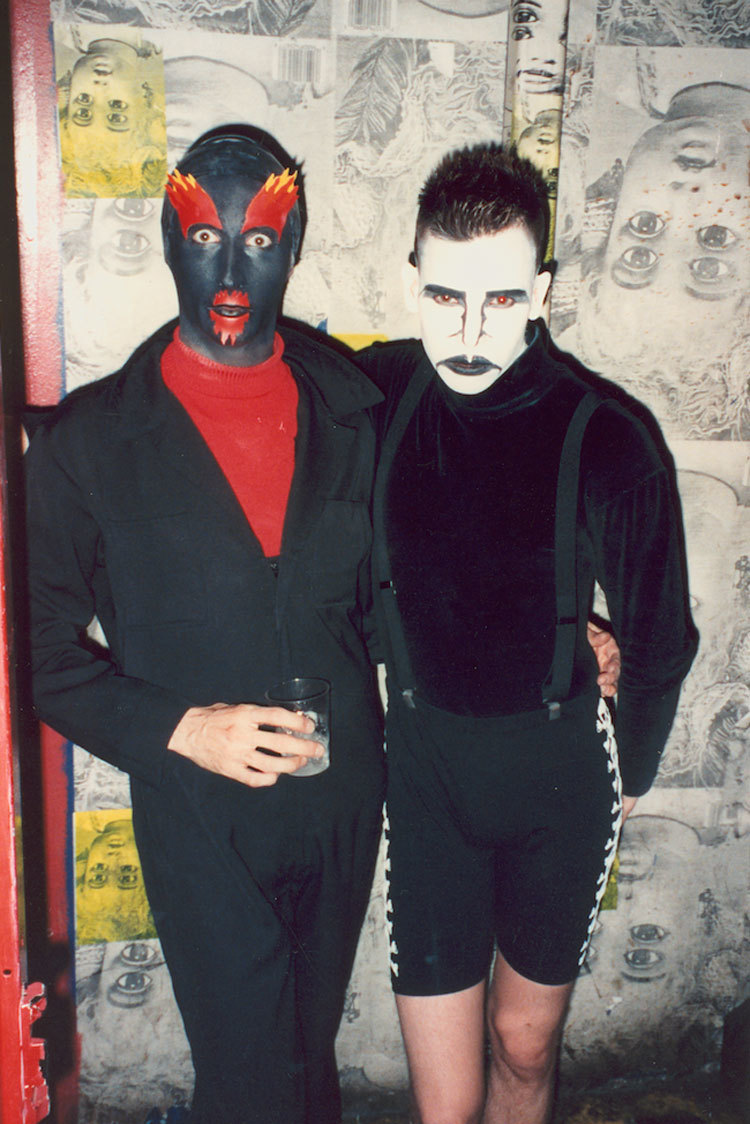

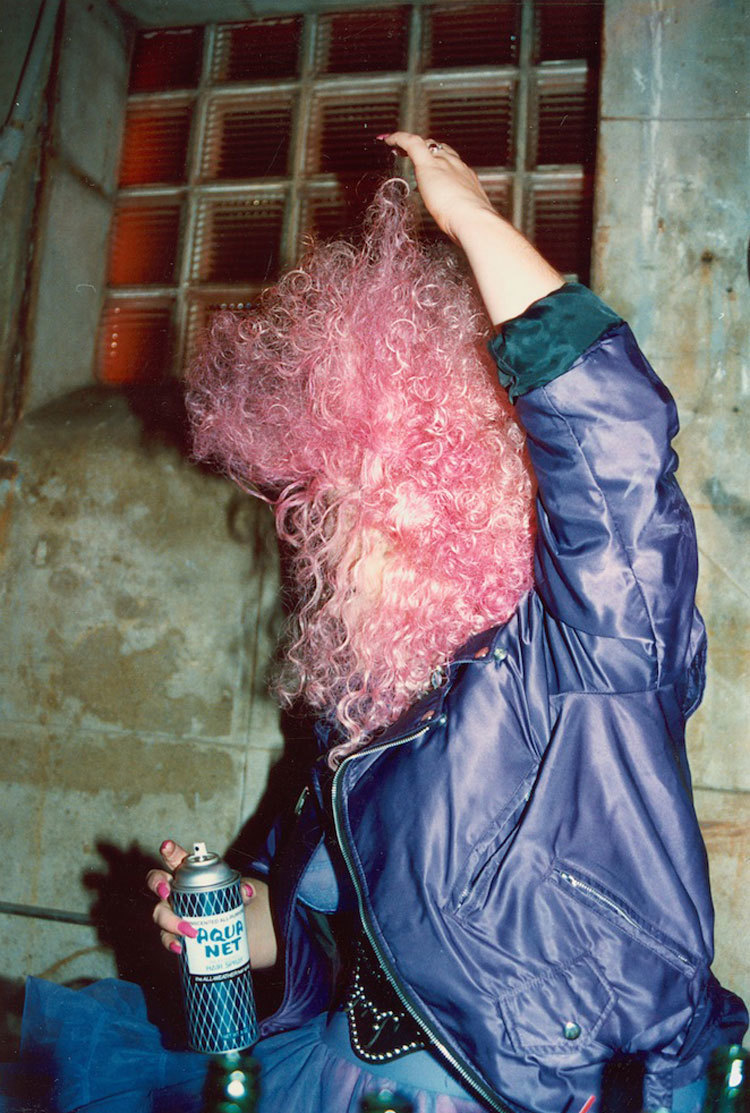

It’s fitting that Shawn O’Sullivan chose Alexis Dibiasio’s images of New York club kids to accompany his new record Fit For Purpose. The New Yorker has spent his career exploring the peripheries of techno, from his early EPs for Shifted’s label to his debut LP under the 400PPM moniker; stripped back, driven, and riffing on the typical dance floor offering. Now, paired with Dibiaso’s images, his explorations turn to meditation on the historical relevance of the genre; “the sense of unease and hysteria that fueled, and continues to fuel, the vital countercultural movements that have shaped club culture.” Ahead of the record’s release, we paired him up with Ernie Glam — original New York club kid and guardian of the late Dibiasio’s images (as well as creator of the brilliant Fabulosity book) — to talk about the wildly flamboyant club scene, and the unabashed hedonism it became infamous for. Press play on an exclusive track from the LP below.

Why did you both feel the images would work so well for the release?

Shawn: Straight off the bat working with this continuity of outsider New York club culture really worked for me. What I found most visually compelling was that the images really captured that moment of the party where things start going wrong. The moment when revelry turns to terror. And for me, that’s a very multifaceted, complex moment.

Ernie: I was interested in working with Shawn on this project after Avian contacted me and asked me to listen to his music. I felt that it was very appropriate for the photographs. Many of them were taken between 1989-1993, which was a time in New York City club culture where the clubs were kind of transitioning from the acid and Chicago house sounds into techno. A lot of what Shawn does is techno music, so I thought it was very appropriate.

Do you share Shawn’s assessment that they document the moment “when revelry turns to terror?”

Ernie: It depends on what your threshold for terror is! My threshold is very high. I agree that people might’ve been terrified if they had been at those parties at those moments when the photographs were taken. I necessarily was not. I had way more to go before my revelry turned to terror. As you can clearly see in the photographs — and Shawn actually came to my house and looked through several thousand of them — there are many different levels of people partying, being really fucked up, drunk, not being drunk, looking really pretty, looking really ugly. So the pictures do capture that process of arriving at the club, looking great, and then maybe leaving the club and not looking that great.

Can you tell us a little more about Alexis Dibiasio who took the pictures?

Ernie: We were friends. I’m 54-years-old, and he was probably about eight or nine years older than me and I noticed him in nightclubs. I realized that this older man had a really big camera with a laser pointer on it and was always at our parties taking pictures of us. And he really stood out because he was older than me, and I was somewhat older than many of the other clubs kids, and he had kind of salt and pepper hair and he had braces, which was unusual. So at one point I just went up to him and asked about the pictures and he said that he really liked our looks and thought we were interesting. We were big posers. Anybody with a camera, we would just oblige them and pose. So that’s how we became friends. Over the years, I realized that his passion was going out and taking pictures of extravagantly dressed drag queens and club kids and he did it every week for years. He amassed this massive collection of photographs. At one point, he moved to Miami and asked me to keep many of them because he thought they would be ruined by the humidity. So I did. He passed away right before the Fabulosity book came out, so he was never able to see it. But I always felt his photographs were this immense, sociological treasure that had to be shared. And the Fabulosity book was the first step in sharing them.

What’s nice is that, while the images are quite nostalgic, it doesn’t feel like a nostalgic record.

Shawn: The images, I feel, are pretty timeless. It’s hard to pinpoint a date. You look at one and it looks like a photo from 1982. You look at another and it looks like a photo from 1993. And then another looks like a photo from 2047. Maybe “timelessness” is the wrong word, but they elude pinpointing a date. They’re achronological.

A lot of them look like the club kids here in London today.

Ernie: I’d agree. I don’t think “timelessness” is the wrong word. If you were to go to the nightclubs in New York City right now, you would see people that look like that. So there is a timeless element. And just by listening to a lot of Shawn’s music on Soundcloud, techno can be very alienating because it’s a very mechanical and synthetic type of music. It can make you feel isolated, because when you’re in a club and hearing that you kind of get in your own head and in your own world. And I think the people that are documented in the Fabulosity book, many of them are products of ostracisation and alienation. And they took that ostracism and alienation that they may have felt in their earlier lives and turned it into this extreme self-expression.

Shawn: Yeah. Isn’t the role of the club, sociologically, from Paradise Garage onwards, all about creating a space from outsiders? Where people who are not welcome in normal life are welcome?

Ernie: That’s certainly the case. The Paradise Garage was certainly full of outsiders and people who did not fit into normal society!

What do you make of the idea of nightclubs as utopian spaces?

Ernie: Well, I think nightclubs are utopian and dystopian at the same time. We all come to a nightclub with our baggage. And a lot of our baggage is from the dystopia outside. But I never thought of them as utopian spaces or places where everyone is equal. Because ever since I started going out there was always a hierarchy and a pecking order, just like in regular society. Yes, you’re free to do whatever you want, but I never thought of them as these egalitarian paradises. Although, I will say now, there is more of an emphasis in New York City clubs on egalitarianism and making everybody feel welcome. I think we’re closer to egalitarianism in nightclubs now than we were in the past.

What do you think the future of the club kid is? It feels as though people are becoming less tribal these days. Will it still endure?

Shawn: Things are definitely less tribal than I think they were. Music does not seem as linked to specific geographical locales as it was five or ten years ago. Let alone 20 years or more. That makes it harder to have a kind of shared sense of purpose and community that bolsters those kind of idiosyncratic worlds. It’s harder for them to exist now. But yeah, I mean there are certain hedonistic and decadent elements of nightlife that I think are just fundamental to the human being. There are aspects of that that will never end.

Ernie: I agree with Shawn. Some humans have this need for pageantry and extravagance and that desire is never going to go away. That’s why in London or New York or other big cities in the world, you’ll see people that are dressed in a very crazy or extravagant way, because there’s this fundamental need that some people have to do that. I dunno if we’re less tribal now. I think the concept of tribalism has changed. In the past, it might have been geographical. And now it’s more like an aesthetic and a self-selection. You can be a member of a tribe on the other side of the planet because of the internet. You can only listen to that kind of music and only fill your life with elements of that scene if you so choose. Whereas in the pre-internet age, you really couldn’t do that. So I think people still are very tribal. In fact, they might be more tribal.

Fit For Purpose is released May 15 via Avian Records.

Credits

Text Matthew Whitehouse