Kehinde Wiley (the painter behind President Obama’s portrait for the National Gallery), Awol Erizku (who photographed iconic Beyoncé’s pregnancy announcement), and Mickalene Thomas (a frequent Solange collaborator) all have something in common. They attended the Yale School of Art.

The prestigious, almost exalted MFA program, established in 1869, has been a pipeline to artistic fame for many. But admission is fiercely competitive. The Yale Daily, the university’s student newspaper, found that only 65 applicants had been accepted from 1,442 for the class of 2010. The program’s recent graduates are also noticeably more diverse, recent alum including artists like Jordan Casteel, Devan Shimoya, Matthew Leifheit. These artists have taken a magnifying glass to complex issues like race and sexuality, making the art world a little less white and boring. Last week, a new cast of starry-eyed, formidably talented diverse artists earned their degrees from the Yale School of Art and, potentially, a golden ticket into the art world.

i-D decided to profile the Yale School of Art’s graduating class of 2018 before they go on to conquer the art world. The graduates of color we talked to are full of promise, creative vigor, and, understandably, anxiety about their futures. “I think that’s where we’re all struggling,” Felipe Baeza, a painting and printmaking student, tells me. “How do we keep this momentum going?” Even though Felipe has secured a job teaching at Cooper Union next fall, the financial difficulties of being a working artist are still very much on his mind. “That’s why I fear going back to New York might not be the answer for me right now. Luckily, I still have my place in New York, but I think the hard part would be finding an affordable studio. Which is why a lot of artists from the program stay behind here in New Haven.”

The students’ experiences were full of highs and lows. They expressed annoyance with the program’s faculty not being very racially diverse. Many used this frustration as a catalyst to form their own insular communities of support, critiquing each other and staging inclusive art events. The two years of intense study and practice were testing, Kenturah Davis, a printmaking and painting student, says, but she came out on the other side stronger because of it. “I would attend this program again in a heartbeat,” she shares. “I’m so glad I did it, not that it didn’t come without its challenges, but it was totally worth it.”

Here, we talk to recent graduates about their hopes for the future, and what attending one of the most esteemed art programs in the world is really like.

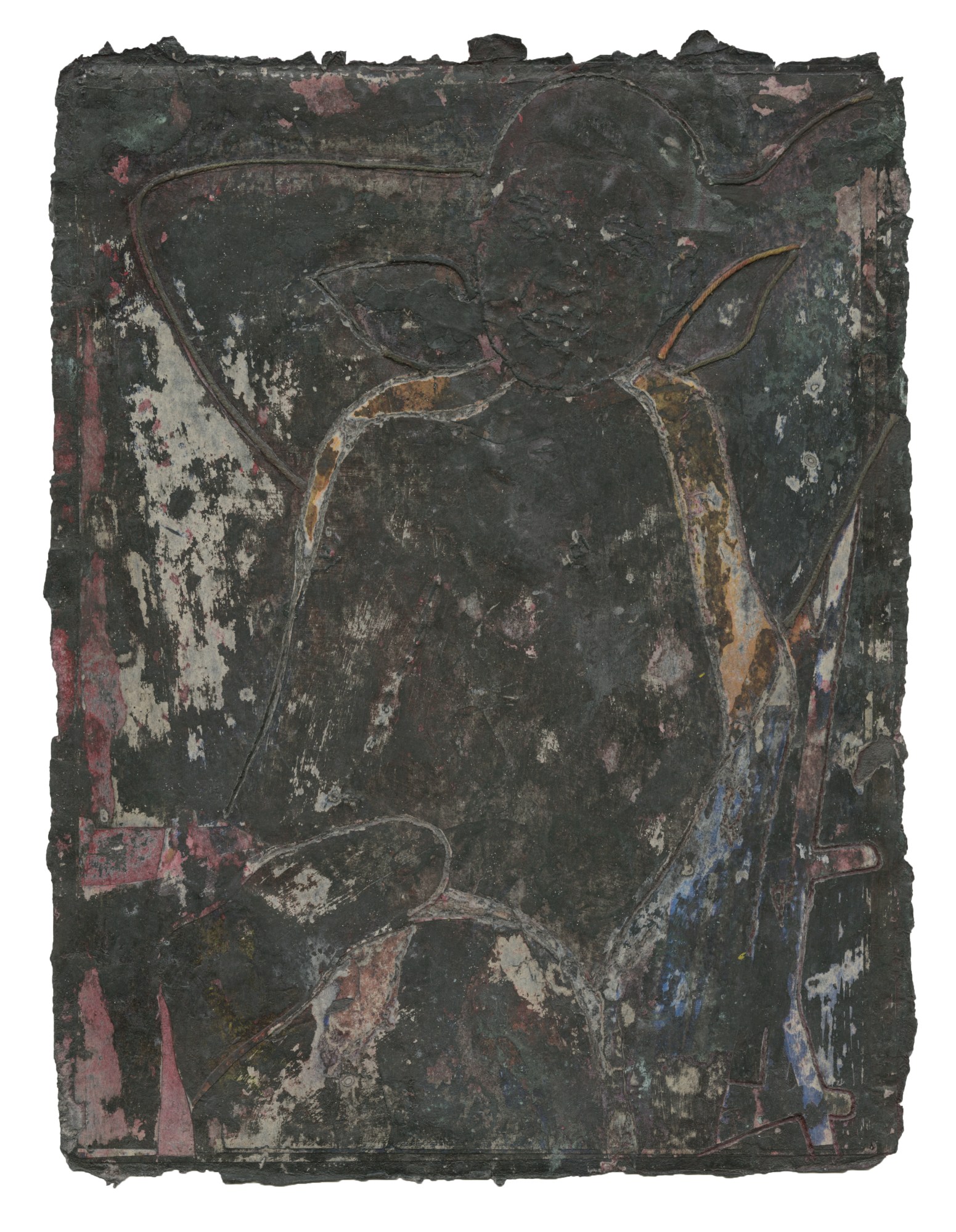

Felipe Baeza, 30, Painting and Printmaking

How would you describe your work?

In the collage work I did, I am still very interested in pornography. All of the pornography I have is print pornography that I’ve gathered. So I’m not going online and printing anything. My interest in pornography, is how the body gets dismembered. Specific body parts are desired more than others. But also how, and I can only speak for gay pornography in a sense, specific bodies get treated very differently and bodies of color are oversexualized but also portrayed in a very hyper-masculine way. These bodies in a way become objects of desire.

I use twine and cut paper in my large papers pieces. In way still incorporating a lot of printmaking techniques. There’s a lot of sanding in the process, in removing and exposing surfaces and textures. I don’t usually use paint. The color that you see on a lot of the work is the actual color of the paper I am using, treated through sanding.

A lot of the work, content wise, hasn’t changed but it’s evolved. I came to the program primarily doing printmaking in a very traditional way. A lot of the work has to do with my lived experience as an immigrant and being an undocumented person. So it has shifted to that and sort of using my art as a tool to create political spaces. Most of my recent projects consider how memory, migration, and displacement work to create this state of hybridity or fugitivity.

How did the class critiques help you?

The good thing about this program is that we have people coming in and out every week, like critics and visiting artists. Those have been the most fruitful conversations, just to have one-on-one conversations with people about anything from art to what is happening in our lives. Also, as peers we would just gather and hang out and talk.

Overall, what was your experience as a person of color at Yale like?

You quickly learn to find your people. I’m not just talking about peers, but also faculty. Sometimes I think it’s hard to talk about my work with people who are coming from an outside experience. I think one of the most magical things in my experience here was when we met Claudia Ranken during my first semester.

I just remember learning to navigate academia and grad school as a person of color, and she said something that stuck to me: “You need to find your people right away, and not every person is going to be that person.” You quickly realize that. I think that was what helped me survive in this program.

What were the most challenging aspects about being a person of color in the program?

As a person of color, there is a lot to teach and a lot to explain. As an immigrant and an undocumented person, I felt like I had to over-explain myself in regards to my situation. For example: a lot of people are not aware that undocumented people cannot vote, so I had to explain that. People of color had to explain that every decision in their work had a meaning, when a white person who was painting was not asked the same questions. That was concerning.

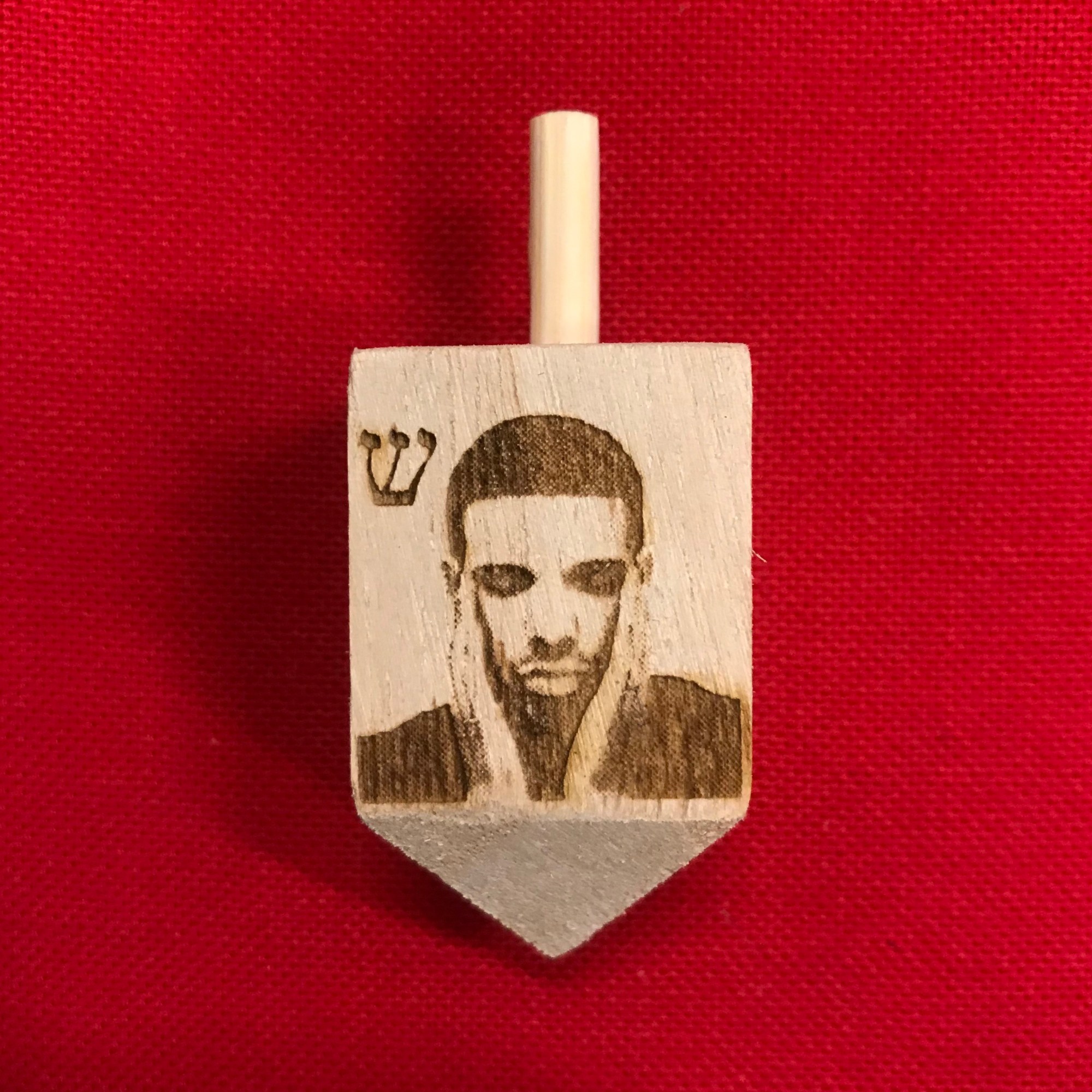

Sula Bermudez-Silverman, 25, Sculpture

How would you describe your work?

Despite being in the sculpture program, l wouldn’t necessarily call myself a “sculptor.” I try to avoid labeling my work, as not to flatten it and reduce it to the status of being an inanimate object. Instead of looking at my work as two-dimensional, I prefer to view it as something that inhabits the entire space. If you’re going to an art program that offers a variety of concentrations, sculpture is the best way to take advantage of all the possible dimensions and mediums.

What were the pros and cons of attending the program?

I feel very fortunate to have made meaningful connections, conversations, and community during my time at Yale.

My one qualm would be that I really didn’t have the opportunity to work with many faculty members of color. It’s been really tough for me in terms of the kind of work that I make. There have been great visiting artists that I felt like I could connect with, but I think in terms of long-term faculty members there were not many people of color. Fortunately, Yale is hiring more faculty of color; unfortunately, it’s happening after I graduate.

I just had my thesis review and we were fortunate enough to select two visiting critics to attend. I really pushed for a black critic: Fred Moten. I think it’s really about having a voice. Just having his voice in the room, honestly. Sometimes it’s about having someone there who has a shared understanding. That was really important to me.

How does your cultural background affect your work?

It’s a big part of my work. I don’t like to simplify my artistic practice only in terms of my racial identity, but who I am and how I’m perceived has a lot to do with how I experience the world. My identity inherently informs my artwork. My racial background is just as significant as any other aspect of my identity, like my gender, sexuality, or class. That significance is reflected in my work.

Were the Drake dreidels an extension of exploring your blackness and Jewish identity?

My Drakels! Yes, I’ve always identified with Drake. Plopping Drake’s expressive face on a dreidel felt like a humorous way to point towards the syncretism I was exploring in my thesis work.

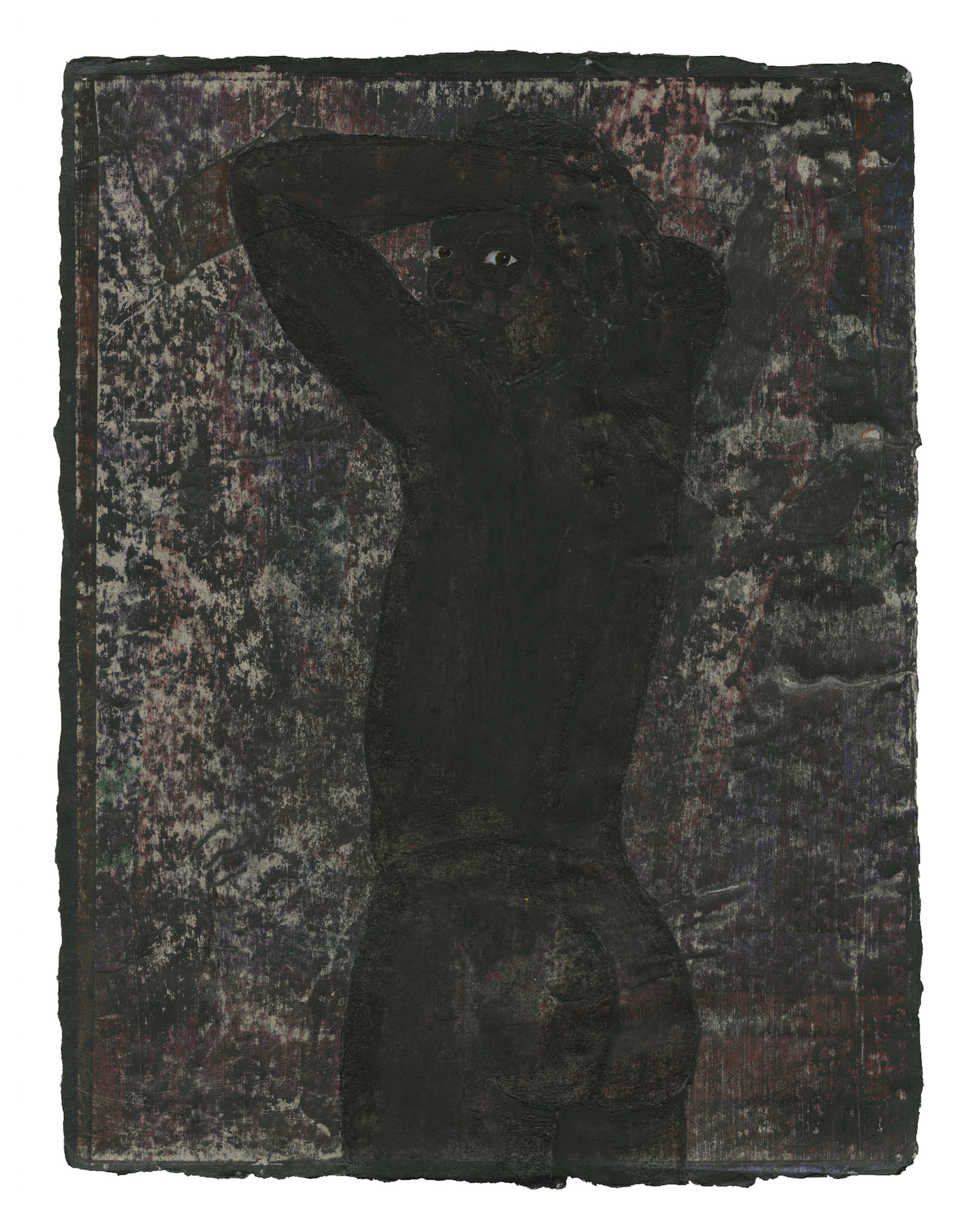

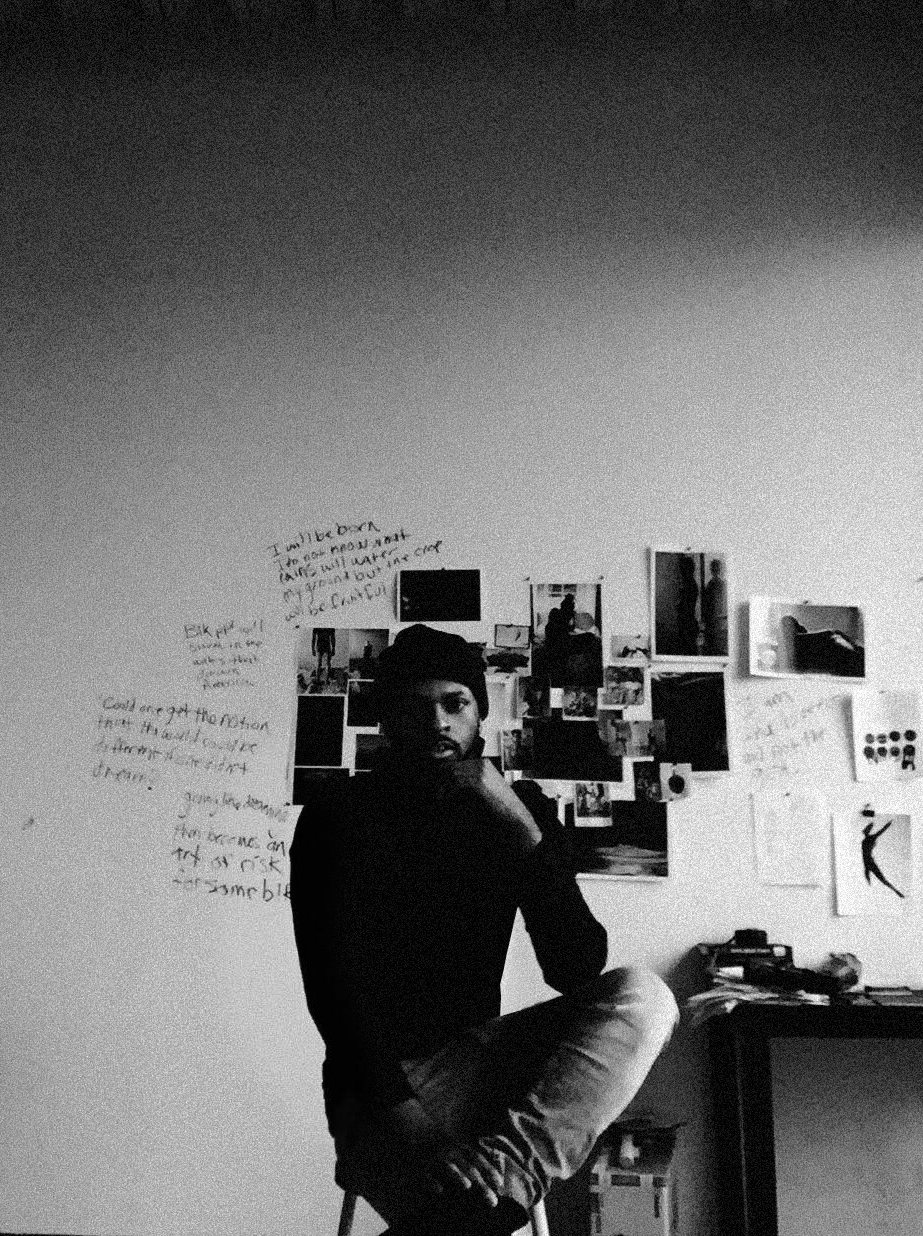

Shikeith, 29, Sculpture

How would you describe your work?

In 2013 I began exploring the psychic landscape of black masculinity. At the time, I was doing that through experimental video and photography. That eventually became a more refined investigation into the different alternative modes of thinking and being amongst black men. So now I explore that through sculptural artwork, video installation, and some writing. I’m looking at more of an expansive scope of how black men learn to be and become over time.

What was putting together and showcasing your thesis project like?

It was a video installation entitled to bathe a mirror. I handled all of the direction, cinematography, and post-production myself. It is a work that conveys, in many ways, the metamorphoses of black manhood through an intergenerational lens. I used filmmaking to illustrate the surreality of the black masculine and queer experience, while journeying through this concept of blueness and what it means for black men to generate blue space. The piece situates itself in sites where black people look to for self reflection , refuge, and reconciliation: the bedroom, the church, the basement, among others. This was my first time being able to bring all those elements and histories into a space through video.

What kind of artistic community did you form while at Yale?

My first year here Vaughn Spann, Jonathan Payne, Kenturah Davis, and myself collectively put together programming entitled “Black Joy,” which looked to black cultural production to create a sense of levity. We invited artists from the New Haven community to just sit and look to black creativity to calm, rejoice, or have a moment of rest. It ended up happening around the time Trump got elected. We didn’t know it was going to go down that way, it just aligned like that. Of course there were incidents where one of the black posters for the event was burned, among other material and information. Having this community already established to do these kind of efforts for the outside community was really significant. It was a significant moment for the School of Art in general.

What piece of advice would you offer someone considering applying to the Yale MFA program?

Yale is not the magic potion to what you think your career will become. All those things you possess before you enter the program are relevant and will remain crucial to your development. Your intuition, your hustle, your imagination. Hold on to those things with a strong grip, because once you let go of them you lose all the ingredients that make you you.

What are some of the biggest things you gained from the program?

I went through all of these different failures to get to trusting my gut and how I need to pace. To get to that point it took a lot of money and wasted materials. But on the upside it really helped me grow.

My first year I was able to take an African-American art history course with professor Erica James, which really did broaden my knowledge of black artists within the canon of our history. Very often when you’re in undergraduate school these artists get left out of the pedagogy of our history. So you have a lot of students who just don’t know any artists of color and they’re in grad school. It’s crazy. So that was a great moment for me to gain access to my history. To know that I don’t exist in a vacuum as an artist.

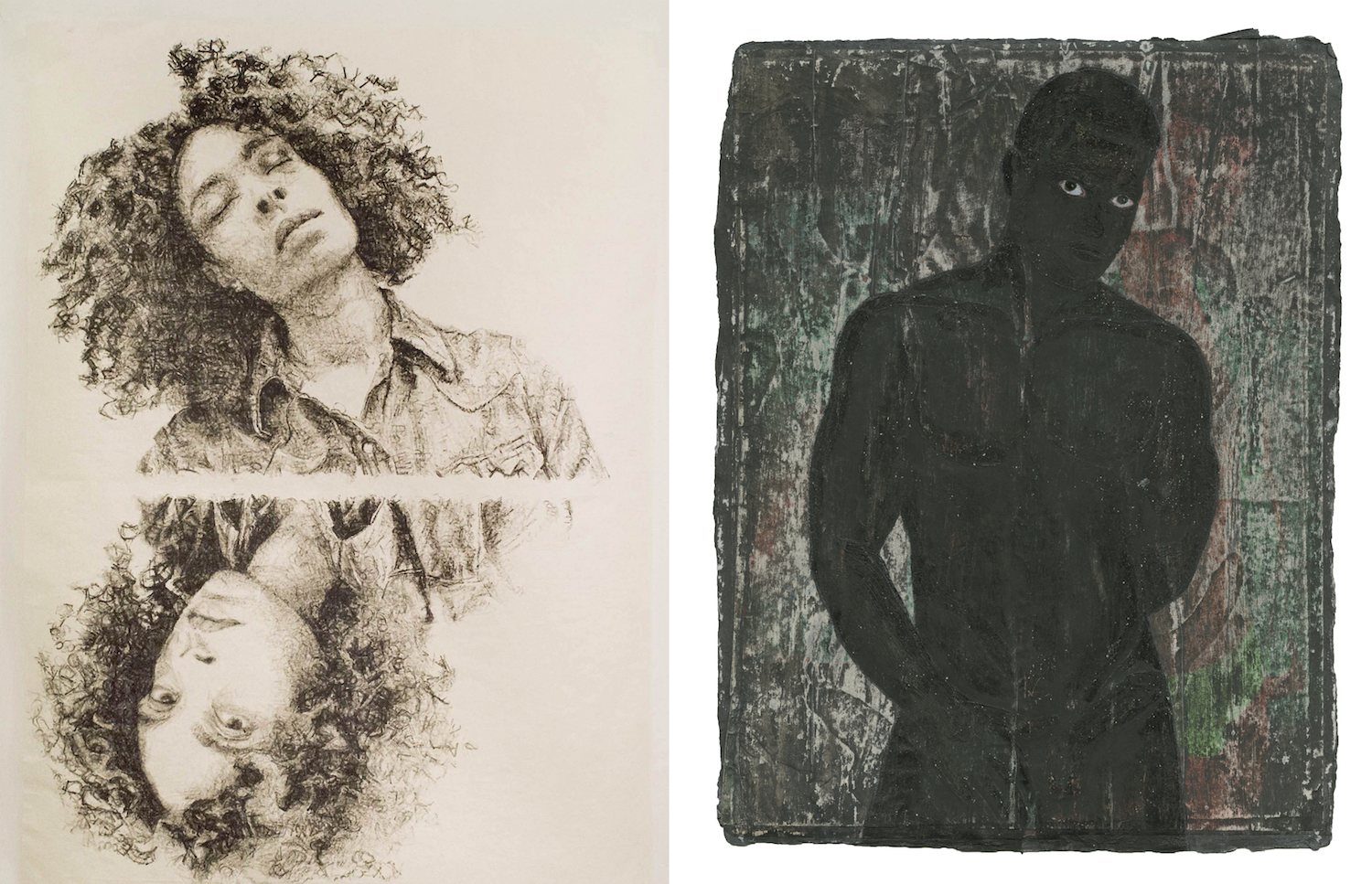

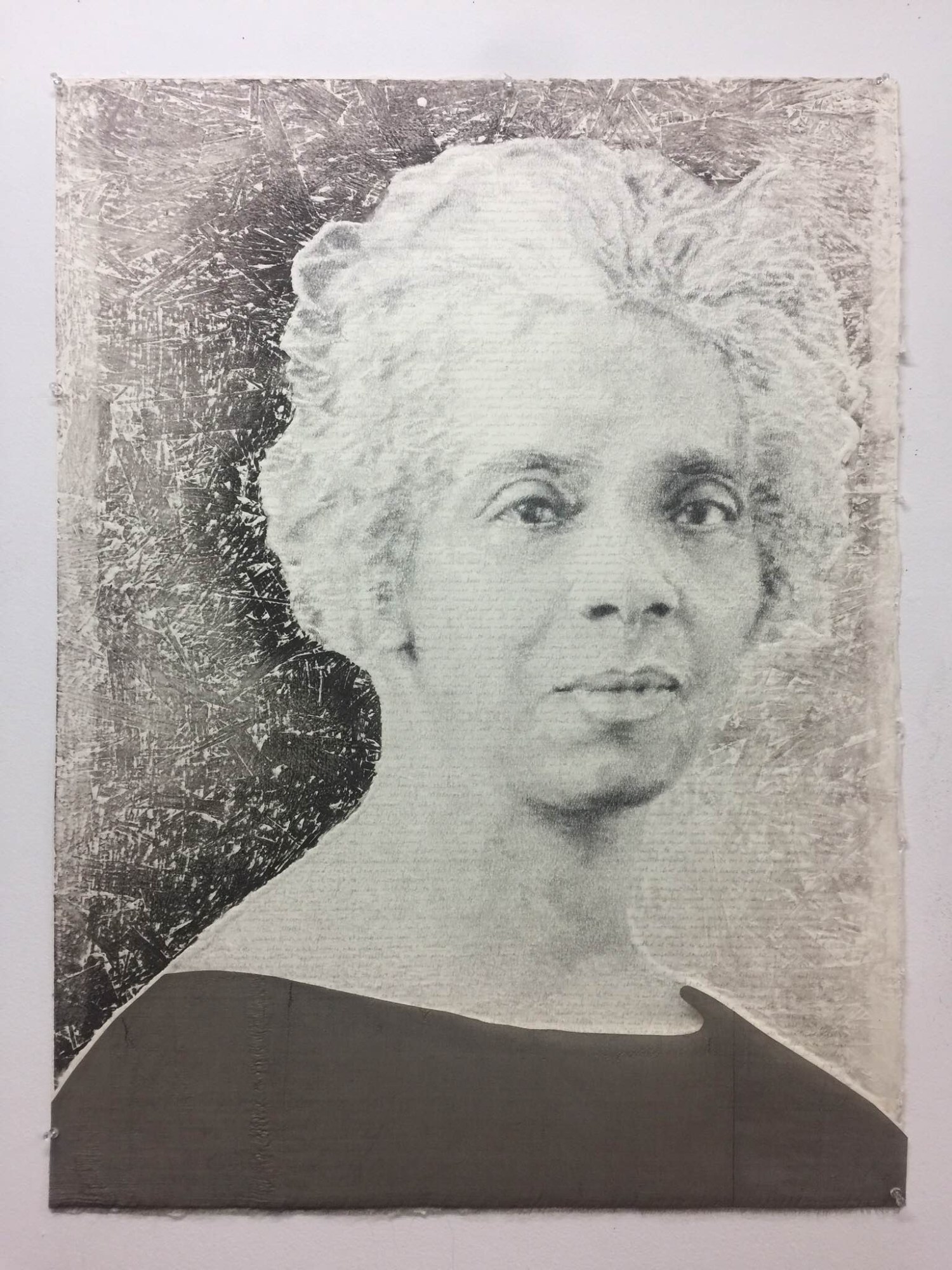

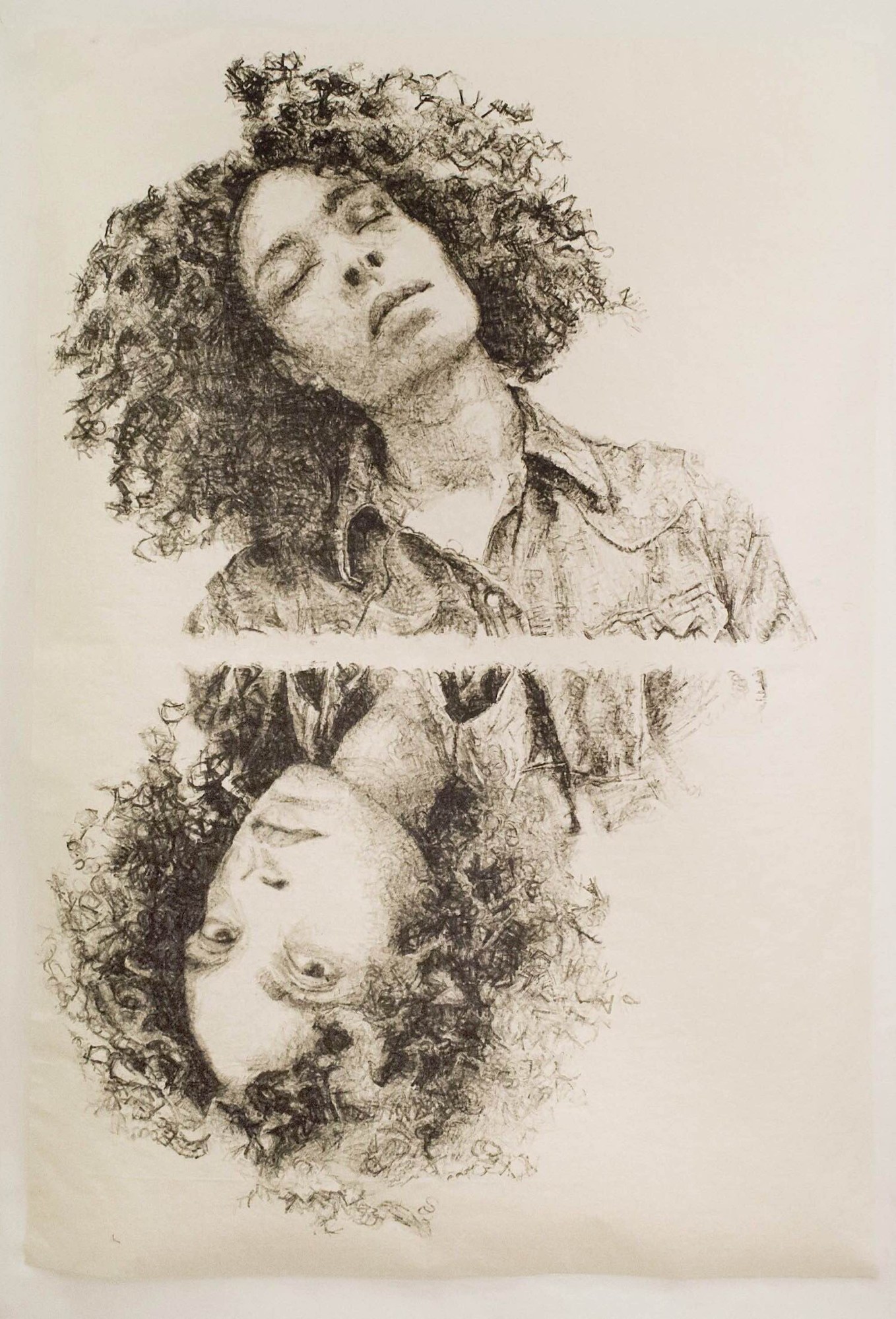

Kenturah Davis, 37, Painting and Printmaking

How would you describe your work?

Before the program, I was rendering drawings by writing the text in repetition in order to think about our relationship with language. When I got here, from the outset I was thinking about how I could push these images to do something else. I’ve been making garments and building structure and, for the past several months, dove into including weaving into my practice.

How do you find your subjects?

Most of them are people I either know very well or have interacted or crossed paths with. Usually I’ve been making the portraits in serial terms, as a series with a specific idea at the output. So sometimes the concept then directs me to who I want to draw. Most of that’s personal sometimes. I get interested in some aspect of an archive. So finding the right archival image comes up as another strategy for making that image. Both of them are personal, and I think that’s kind of a preference of mine unless there’s some sort of historical interest that drives the series.

What motivated you to go to grad school?

I’ve been thinking about it for a long time. For a while I had gallery representation in LA. At the time, it seemed possible to continue down this path without feeling a need to go to grad school. I actually really like school, it’s an explorative space. Without it I think I might of have stay more focused on my portraits. But I didn’t want to feel stuck with a thing that is more singular than the other forms I have been trying out recently. My thought was, ‘I’ll apply to the schools I admire from a distance and from their reputation seems really challenging and see if I get in and if I get in, that’s great. And if not, I can keep hustling in this other kind of way.’

How did the program help you get to the next stage in your craft?

Here, you’re kind of challenged to extend and experiment. I think I’m one of the older grad students in the program, so as a result of kind of living a life in the professional world between undergrad and grad school, I wanted to make sure I used the time here to try other things. It was already something I wanted to do, but the pressure from the faculty in the program was to really use this time to experiment. That pressure is really palpable and that alone helped to push me in ways that surprised me. How the experimentation manifested I never would of anticipated.

What was your favorite part about the program?

What I liked about the program is we had access to the rest of the university. We were required to take at least two classes outside of the School of Art. The first year, I spent probably spent most of my time in classes outside the School of Art. There’s a really great anthropology class called “Meaning and Materiality” and that was really invigorating. I also took one philosophy class called “Language and Power.” That was important in helping me think about the intersection of writing and drawing in my work, and thinking about our relationship with language and how power is introduced.

What’s next?

My hope and dream is to continue as a working artist and figuring out how to do this full time. I do want to continue with my portraits, and even working with other materials has helped me rethink other things I can introduce back into the images.

Responses have been condensed and edited for clarity.