Moffy Gathorne Hardy grew up in London with her painter mum, pianist step dad, and whoever else needed the spare room at the time: a cousin, a friend, her old chemistry teacher — and various other waifs and strays over the years. An only child, she spent her years fraternising with adults. That and her old best friend, with whom she’d while away the long school nights pillaging whatever make-up they found lying around the house.

Born with strabismus, an optical condition where your eyes don’t align, she often had a hard time relating to people. Not being able to make eye contact, as a child, and more crucially during those awkward teenage years, often made her feel invisible. But she’s learnt to live with it. In fact, she doesn’t just live with it, she celebrates it as a little indication of the kind of human being she is.

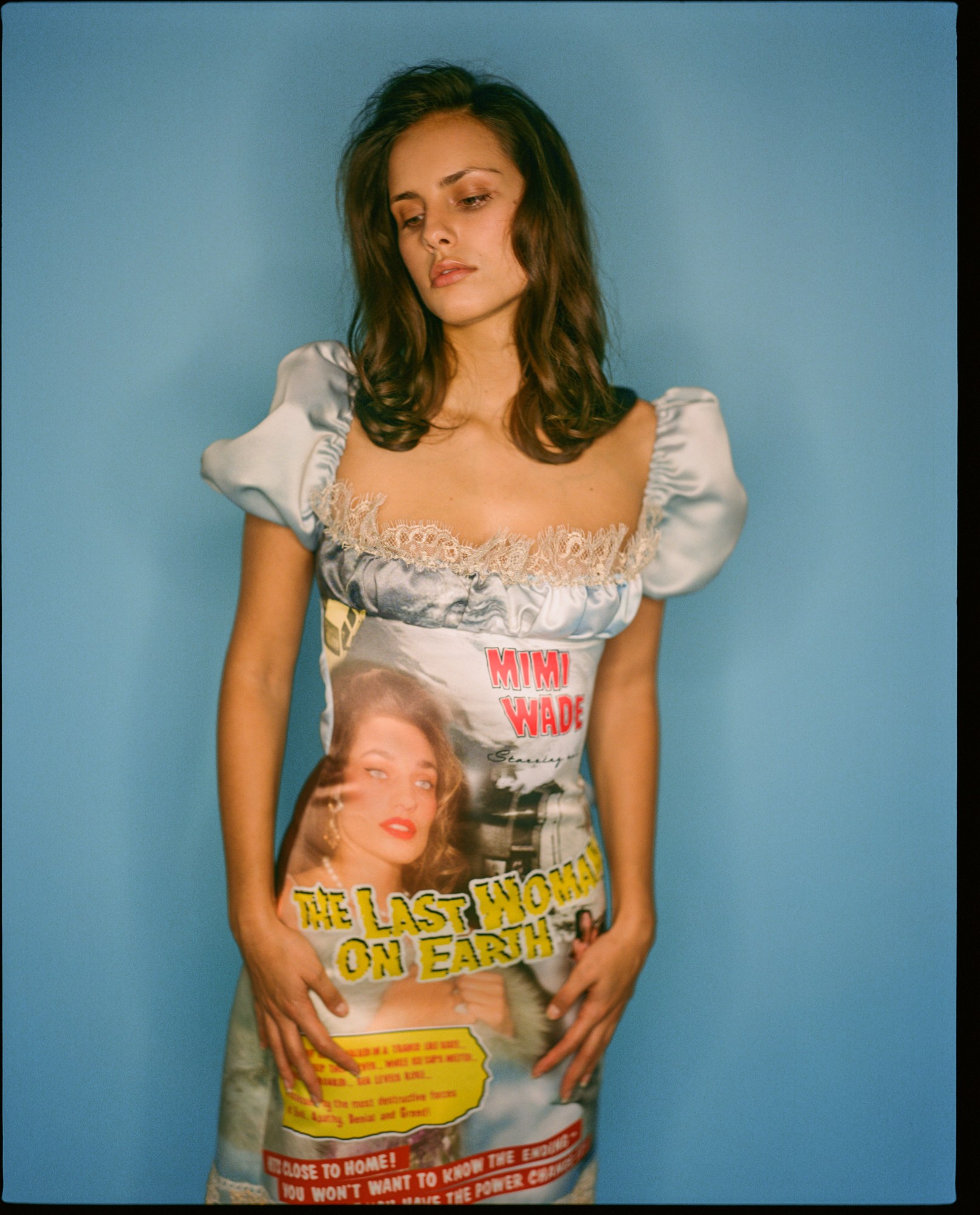

A unique beauty, Moffy made her modelling debut back in 2013, when photographer Tyrone Lebon shot her for the cover of POP magazine, after the two were introduced by his then girlfriend Adwoa Aboah. Since then, she has been snapped up by designers Mimi Wade and Vivienne Westwood, appeared in the pages of niche zines Document Journal and Buffalo, and continues to challenge societal norms wherever she goes. In between shoots, she’s currently writing her first novel, which in reality is “10% name changing, 80% thinking about writing, and 10% actually writing.” It’s coming along nicely.

Here she offers us a lesson on beauty.

“My prevailing memory of being young is that there were always art books knocking about, music playing, and things being talked about. I’m an only child so I spent most of my childhood speaking to the grown-ups around me, where a love of The Beatles and an interest in reading was never discouraged.

When I was seven or eight my godmother sprayed me with a perfume and told me it was what the beaches of St. Tropez smelt like in the 60s; besides the seductive description it was the most delicious thing in the world and I never forgot it and looked for something with the same smell for about ten years, until I found Nuxe Huile Prodigieuse which I still use almost everyday. Hilarious and quite comforting to think my taste hasn’t changed in fifteen years.

I first started wearing make-up in primary school; we used to sneak mascara and lip-gloss from Claire’s Accessories into the loo and try it on. I’m not sure how it made me feel in reality, but I was hoping to feel more grown-up, and prettier; I think it was that straightforward.

I would also go to my best friend’s house every day after school, and along with the solemn ritual of covertly buying thongs and push up bras from Primark and trying them on in her bedroom, we would take it in turns to do make up “looks” on ourselves using a vast eye shadow palette that probably used to be her mum’s, and then explain to each other, “I’ve gone for a navy blue smokey eye with a subtle lip”; the kind of thing you say when you’re nine years old, you wish you were a big girl, and think that brown eyeshadow is the height of sophistication.

I’ve never used make-up as a means to express my true self, but as a form of escapism, engaging with a fantasy in the way that you do during fancy dress; it’s a way of assuming and trying on other identities. I don’t use it in the conventional sense: accentuating features already present, highlighting cheekbones etcetera, but I love green mascara, black lipstick, anything fun and a bit silly.

As a kid I never felt beautiful. I was a funny, specky, little thing with an eye patch, glasses, and a hand me down cardi; not an aesthetic you tend to appreciate when you’re five. I’ll never forget starting secondary school and realising that boys fancied me, I couldn’t believe my luck!

“Whenever I saw someone else with a lazy eye my negative identification was such that I could hardly bear to look at them.”

Sometimes I’ll say hello to someone and they won’t realise I’m talking to them, which bothered me immensely when I was younger. For this reason I used to associate having a lazy eye with being invisible, anonymous, with not being able to relate properly, with a feeling of being stuck behind glass — a horribly claustrophobic thought for a child to be carrying around. What’s more, whenever I saw someone else with a lazy eye my negative identification was such that I could hardly bear to look at them.

Eye contact is a way of acknowledging other people and in turn having your existence acknowledged. Not being able to really achieve it, in that sensitive period when you’re going to school, individuating from your family, and trying to find out who you are, is agonising. So I was ashamed of it, although I only articulated it to myself in these terms much later, I suppose when I had enough separation from it.

Having spent years trying to conceal it when meeting new people and going through all kinds of absurd acrobatics to avoid having to address one person within a group, my attitude towards it changed completely. I think one can assimilate anything as a part of one’s identity if necessary, and having had the option to have it operated on and declined it, I now feel that it’s a little indication of the kind of human being I am; that I have a slightly unusual lilt of mind or way of perceiving reality, and where previously I wore it like a mask, it’s now a way into knowing me.

I think feeling beautiful arrives at the moment of self-actualisation, of knowing who you are and feeling that you’ve fulfilled what you’re capable of, so it takes a while ! I would suggest doing something creative, which can serve as an external mirror, and being around people who are kind and non-judgemental.

These days I feel most beautiful when I’m pissed outside the pub giving the “Haven’t you missed me?” look to whichever ex I’ve bumped into on that occasion. Not really! At home with my boyfriend and my codependent and socially anxious sausage dog, Razzy, I can’t think where she gets it from….”

Credits

Photography Louie Banks