Kuwait-born, New York-based Parsons School of Design student Taiba Al-Nassar created 3asal magazine to celebrate the oft-overlooked multiplicities of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) women. While stereotypical Western representations commonly present them as “exotic” or “submissive,” 3asal, which translates to “honey” in Arabic, showcases the “infinite complexities” of their identity.

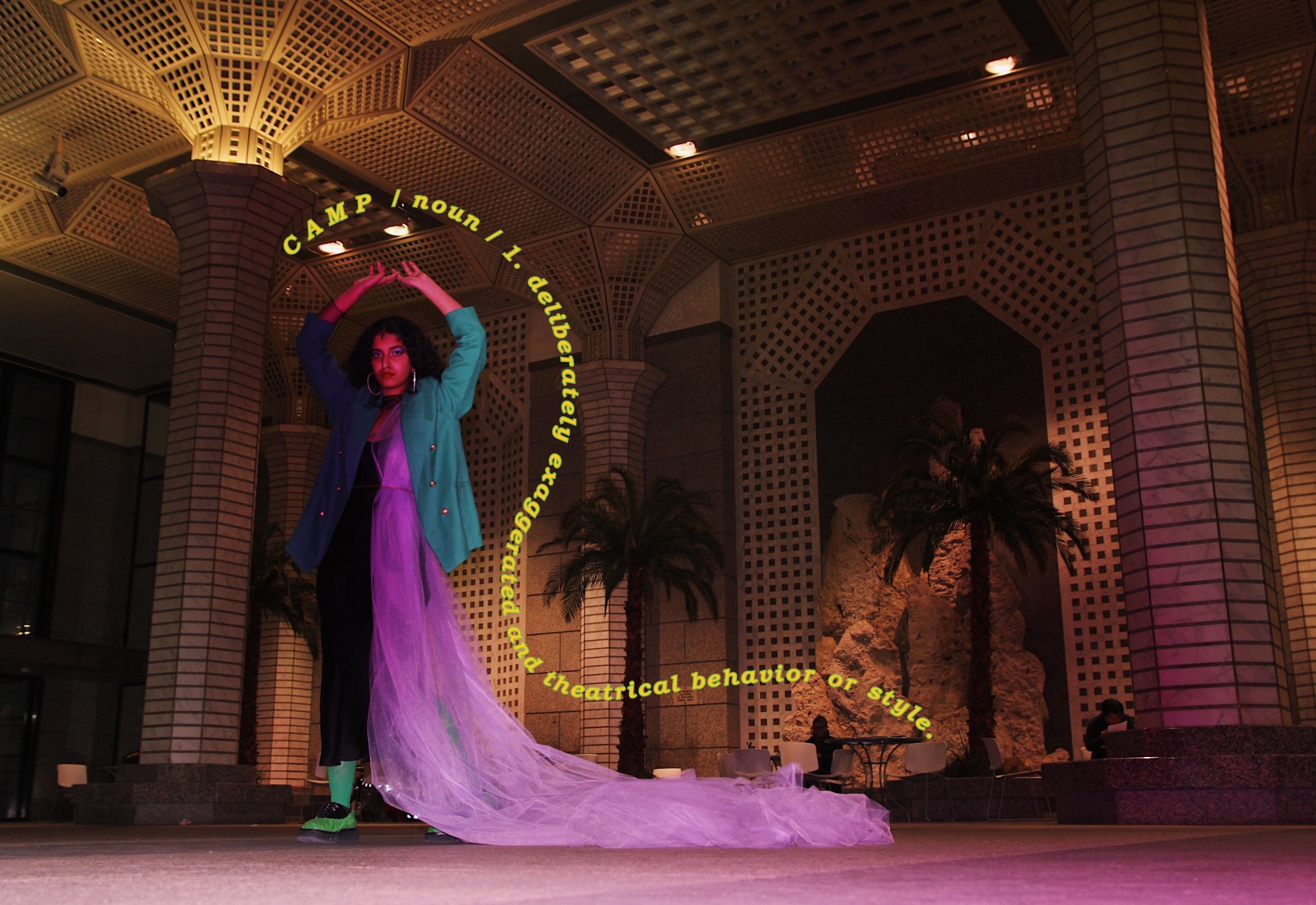

Spanning art, photography, and writing, the first issue includes everything from an interview with the founder of Yalla, a Brooklyn-based collective uniting New York’s LGBTQ+ MENA community, to an exploration of the legacy of Egyptian cinema. Additionally, there’s a spread by Jeddah and London-based creative and stylist Latifa Bint Saad, who pays homage to the screen sirens of the Golden Age—only re-imagining MENA women as the stars rather than simply as extras.

3asal is part of a growing number of collectives created by women of MENA heritage across the UK and the US increasingly redefining what it means to be of MENA descent today. What sets it apart, however, is its commitment to reflect not just the experiences of girls from the diaspora but those from the region too. In this sense, 3asal is as relevant to a reader from Brooklyn as one in Beirut. Or as Taiba says: “Being a diaspora kid has its own set of privileges. I’m happy that girls in the motherland can go to 3asal to fill that gap”.

With 3asal’s inaugural issue now released, i-D caught up with Taiba to find out why it’s time for MENA girls to finally take ownership of their identities on their own terms, why they deserve a new narrative, and what she hopes to achieve.

How did 3asal come to be?

I created 3asal because it was necessary. It’s the platform I craved my whole life as an Arab girl. So many of us grow up with shame and resentment towards our identities when we don’t see ourselves celebrated in the media. As a kid, not seeing myself in the media that I consumed made me view myself as inferior to the blonde, blue-eyed American girls I’d see plastered everywhere. I rejected my culture for years because I wasn’t shown its value. As I get older and learn to embrace my identity, I want to erase that experience for the younger generation of MENA girls. It’s so important for them to have access to platforms and images that embrace us and that were absent throughout lives as we abandon conformity.

Let’s talk about 3asal’s name…

I love the word 3asal. Always have. It rolls off the tongue so sweetly. In MENA culture, 3asal is a term of endearment often associated with femininity and sweetness, things that are innocent and palatable. In this way, it also directly reflects the strict gender binary of a woman’s role in MENA societies. I called this publication 3asal because it redefines the word to fully embody the identity of the MENA woman. It extends the word’s traditional associations to embrace our infinite complexities. We can be kind and gentle and beautiful and strong and resilient and cheeky and loud. 3asal is about celebrating it all.

How important is 3asal in a climate that more often than not reduces MENA girls to orientalist stereotypes?

Because it’s a space strictly for and by us. The writing, the photography, the styling, the illustrations and art—everything. No outsider is trying to make sense of our existence or attach these false narratives onto us in 3asal. We’re no longer accepting outside voices analyzing and telling our stories. The conversation is ours to be had in the communities and platforms we build.

Do you think MENA girls aren’t celebrated enough in both their region and the wider Western world?

Because of the stigma that accompanies our visibility, it’s definitely rare. I don’t blame this entirely on the media though. So many of the girls I work with are super careful about how they’re depicted in the images we create because of who will look at them and what’s accepted in our community. A lot of times we still have to tip-toe around cultural norms when it comes to styling or even the angle of a photograph. So I think we still have a lot of work to do within the community when it comes to freeing our girls from confines like honor codes before we can be fully embraced by the media. It’s a delicate process that needs to start from within before we can even begin to bring the West into the conversation. With platforms like 3asal and the heightened consideration of regional media outlets, we’re triggering a very necessary cultural shift.

A number of art collectives and zines created by women of MENA heritage in the UK and the US are re-defining what it means to be a woman of Middle Eastern heritage today. How does it feel to be part of this? And how does 3asal differ from other media in the MENA region?

They’ve had such a special place in my journey for years. I’m so honored and excited to contribute to the dialogue they’ve created. I’ve always been fascinated by the experience of the MENA diaspora. I appreciate the exposure to experiences beyond my direct community that they’ve helped give me as it was so important to represent all experiences in 3asal. When I was growing up, I could never fully identify with the stories of, for example, a British Arab girl from the position I was in sitting in my bedroom in Kuwait. So I’m happy that the girls in the motherland can now go to 3asal to fill that gap.

Logistically, how did putting the issue together work?

I pretty much started 3asal completely on my own so the majority of the bigger stories in the issue are shot and conceptualized by me. When I kind of knew the direction I wanted to take 3asal, I opened it up for collaborations and submissions. So many girls from around the MENA region sent me their work, which I’m so honored to have received and been trusted with. Latifa Bint Saad was one of them. Her editorial “Glamor Girls” ended up being one of my favorites in the issue. Another favorite was the “Tell Me Your Story” editorial, which was a collaboration between myself and New York-based photographer Mashael Al Saie.

The best part of the process has been meeting so many MENA girls from around the world that have come together for 3asal. It has been so special to work exclusively with girls that come from a collective set of backgrounds and experiences knowing that we have no intentions outside of creating something beautiful for ourselves and our community.

Finally, what does it mean to you to be an Arab woman today?

It means reconciling bits and pieces of my culture and history and choosing to shed what’s no longer relevant to me. It’s taking pride in my identity. It’s sharing the love I’ve found for myself and where I come from with all my sisters that aren’t quite there yet. It’s also wanting the absolute world for the next generation and doing everything I can to give what mine was deprived of. Change is happening so fast in the region and it’s so exciting to be a part of it.

Order 3asal Magazine Issue One online here

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.