When it comes to seminal queer film, nothing captures the resistance against sexual and racial tensions with such fervent energy as Tongues Untied.

The documentary — released as a collective response from black gay men to the AIDS crisis which ransacked black and gay communities in the 1980s — furiously confronted institutional and social ‘silence’ around a crisis that threatened black gay men with extinction. After the sexual revolution of the 1960s shifted the discussion surrounding sexuality from deviance to liberation, the AIDS crisis ushered in a renewed era of moral conservatism under the Thatcher and Reagan administrations in the UK and US.

Sexuality once again became reduced to those sinful exchanges of blood and semen: sex therapist Dr Theresa Crenshaw concluded in 1987 that “the sexual revolution is over.” Gay people, black people, sex workers, trans people were viewed as a public health threat to the heterosexual, white majority.

Tongues Untied, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this month, was released at the American Film Institute Video Festival. Directed by Emmy Award-winning Marlon Riggs, and interspersed with street poetry from Essex Hemphill, the film is a rich tapestry exploring the multiplicity of black gay life in the United States through an enmeshment of dance, performance, monologues and rap. It is interspersed with archive footage of black queer social spaces, protest marches, and scenes of police brutality. It looks at the men denied entrance from a jewellers because they are black males, “all perceived as thieves,” who are beaten mercilessly if their jewellery betrays “pigments of faggot.”

In the eyes of many at the time, black gay men were seen as being contaminated by their race, contaminated again by sexuality, by the virus which carried with it medical and social death, they were in many ways, the ultimate emblems of sin and degeneracy.

Within a hostile environment which framed our interactions through the language of illness and pathology, what Tongues Untied did 30 years ago is reintroduce conceptions of intimacy, love, passion and desire as the dominant behaviours which govern black gay lives. On its release, the film was met with widespread controversy and attempted censorship from conservative pundits. As an LA Times article from 1992 notes, scenes from Tongues Untied were broadcast in homophobic advertisements by Republican politician Patrick J. Buchanan attempting to present the film as a male orgy, and connect controversy around the public funding of “repulsive” art to political rival President George W. Bush. The film is not pornographic at all — a scene of two men in bed together barely even reaches foreplay.

But the film was so disruptive to institutional conservatism because it dared to embarrass the US government, and made clear that all those who are silent on the crisis surrounding black gay men were complicit in their deaths. Marlon refused to be silent, not only by shouting loudly about government and social neglect, but also by archiving our lives — how we danced, how we laughed — because erasure of community and culture is an equal form of death.

Tongues Untied is so touching, aside from its more serious grapplings, because of the way it engages with the most casual of our behaviours to explore black gay culture. In one section of the film, we’re gifted with a “basic lesson in snap”, courtesy of the Institute of Snap!thology. Snapping — the art of clicking your fingers — can come in many forms, from the ‘medusa’ to the ‘domestic’, and can serve many purposes: “to read, to punctuate, to cut.” “A sophisticated snap is more than just noise”, in the same way that it would be insulting to describe vogueing as simply dancing — it’s successful execution is dependent on precision, pacing, placement, poise. Knowledge like this is often lost in the same ways much verbal slang, like “shade” and “yaaas” become appropriated from black queer communities.

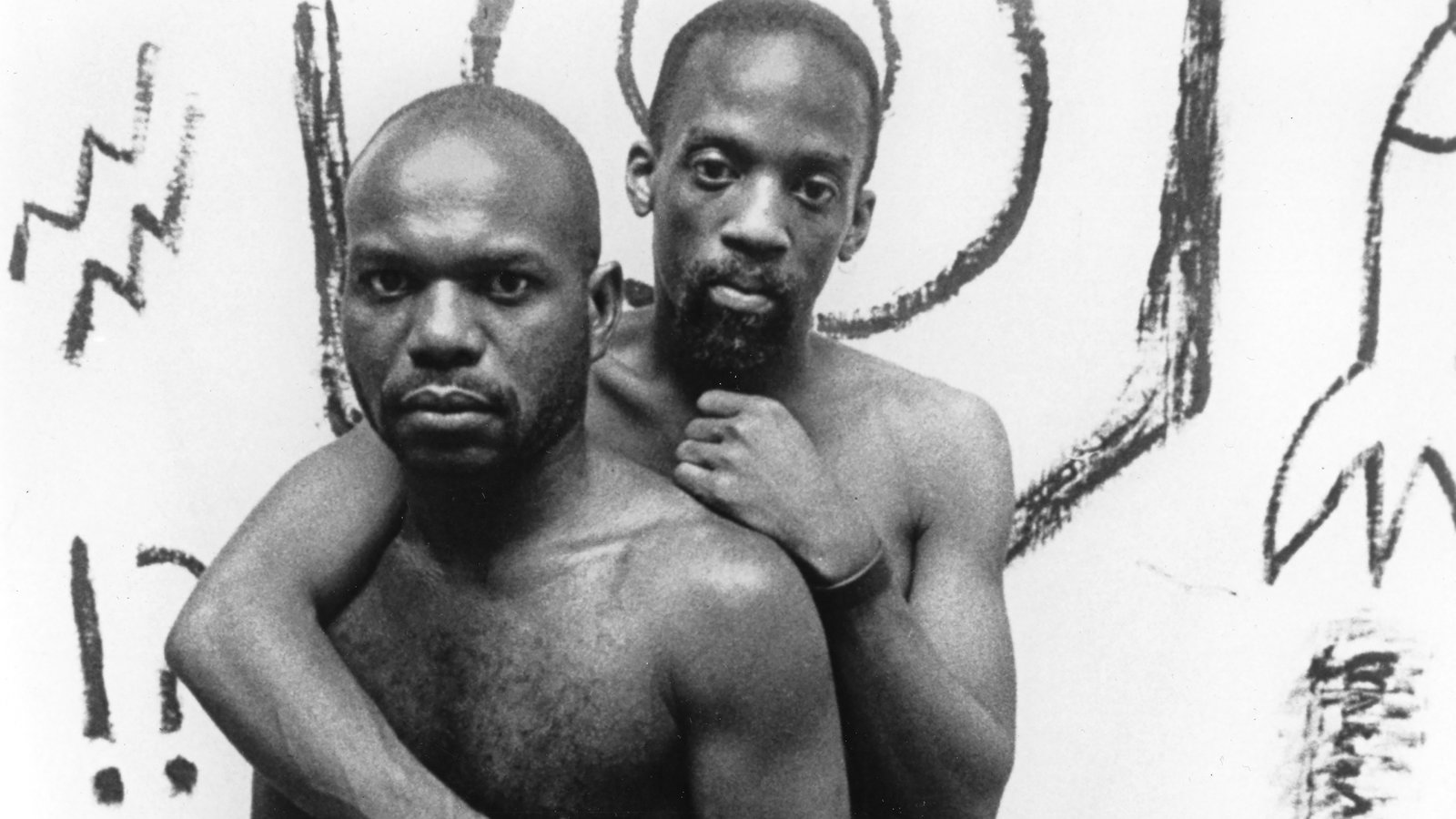

As Marlon presents the cultural trends black gay men have pioneered, he also explores sex and intimacy between black men, and while not the sexually explicit film its critics claimed it was, it doesn’t shy away from the fact black men have sex with each other.

“You’ve reached ‘Black Chat,’ your hotline to the best black numbers. Want to connect with a Banjee-Boy, press 1. For a versatile Butch-Queen, press 2. Or looking to commit mind and body to a BGA, press 3. Don’t be a shy guy. Make a choice, and meet that special man. Good choice. Now leave a message. You have a minute after the beep.”

Before the internet, sex chat hotlines were to many black gay men what Grindr is to us today. Apps and modern gay subcultures encourage us to divide ourselves by ‘tribes’ — bears, twinks, otters — but black men have often expressed that these ‘tribes’ don’t feel designed with us in mind. Instead they validate different ways to be attracted to whiteness. In the film, ‘Black Chat’ offers “Banjee-Boy” and “versatile Butch-Queen” as categories defining black men’s attraction to each other. Although there’s plenty to problematise about how we segregate ourselves based on physical presentation and sex position, this scene provides a rare glimpse into how sex and attraction is defined within black gay people. In many ways learning the difference between a “Banjee-Boy” and a “versatile Butch-Queen” is a kind of community sex education that has always existed within social networks, but found a platform and immortality through Marlon’s film.

30 years later, I also find the message “Black men loving black men is the radical act” quite striking. Viewing black gay men loving each other is something that brings me so much joy not only because love is awesome, but because this is a kind of love that has been haunted by mortality and attempted censorship.

And Marlon’s message came at a time when black men loving each other was fraught with risk of death. As a scene portrays two black gay men giving into their passions, Essex Hemphill recites: “Now we think, as we fuck, this nut might kill us. There might be pin-sized hole in the condom, a lethal leak.” This line has always stuck with me because here Essex really captures the mental negotiation of pleasure and risk that comes with sex. As black gay men in the UK and US still face a disproportionate HIV epidemic, the persistent associations of our sexual pleasure with disease and death are unfortunately not lost.

Black gay life is not defined by premature death, but each death you learn of feels personal. I was born in 1997 and one year after my birth black British gay footballer Justin Fashanu died by suicide after being harassed by homophobic British media. For many years he was the only black gay man I knew of, and I thought I would die like him. I felt distress after I first watched Tongues Untied, researched those who starred in the documentary, and found that they had all died young, and usually from AIDS-related complications. My heart feels heavy when I see that young black gay men today are preyed upon and exploited, as we have seen in the deaths and overdoses of young black gay men in the home of Democratic donor Ed Buck. So, even though I’m not the biggest fan of representation politics as this great liberator of marginalised people — seeing Moonlight, or the black gay relationships in Pose and Empire, helps me to imagine futures people like Marlon Riggs and Essex Hemphill were not able to witness — of black gay love persisting, of two black men growing old together.

On Tongues Untied’s 30th anniversary, reflecting on the vitality and endurance of black gay life feels bittersweet. It is, after all, of no comfort that black gay life has to endure against challenges which today still don’t feel far removed from the extremity of what is explored in the film. What black queer communities may take from the film is a radical message of love — one found in collective community protest, in the arms of another man, or in the lessons shared to you by a black gay elder. Love has always been the blueprint for navigating a hostile environment. As institutional and social neglect continues to leave us vulnerable, black gay people have often relied on each other for community care. Black gay love was then, as it is now, about preserving and saving our lives. The film instructs black men to fulfil this duty. It ends with the words of Joseph Beam: “Black men loving black men. A call to action. A call to action. An acknowledgement of responsibility. We take care of our own kind when the nights grow cold and silent. These days, the nights are cold blooded and the silence echoes with complicity.”