Midway through the first episode of Unorthodox — Netflix’s acclaimed drama about a young woman’s flight from New York’s Hasidic Jewish community — actor Shira Haas unpeels her tights, tentatively walks into Berlin’s Lake Wannsee and removes her sheitel. It’s a beautiful metaphor for the transition that Esty, the lead character, is about to embark on, says Justine Seymour, the show’s head costume designer and a key figure behind its authentic portrayal of the closed Satmar community.

“I thought it was so brave”, costume designer Justine Seymour recollects as we speak over the phone from her home in LA. The designer took her own personal experiences to the job; towards the end of the interview, Justine shares that she was raised in a religious cult. When her daughter first introduced her to the best-selling memoir by Deborah Feldman, upon which Unorthodox is based, she knew it was a perfect fit.

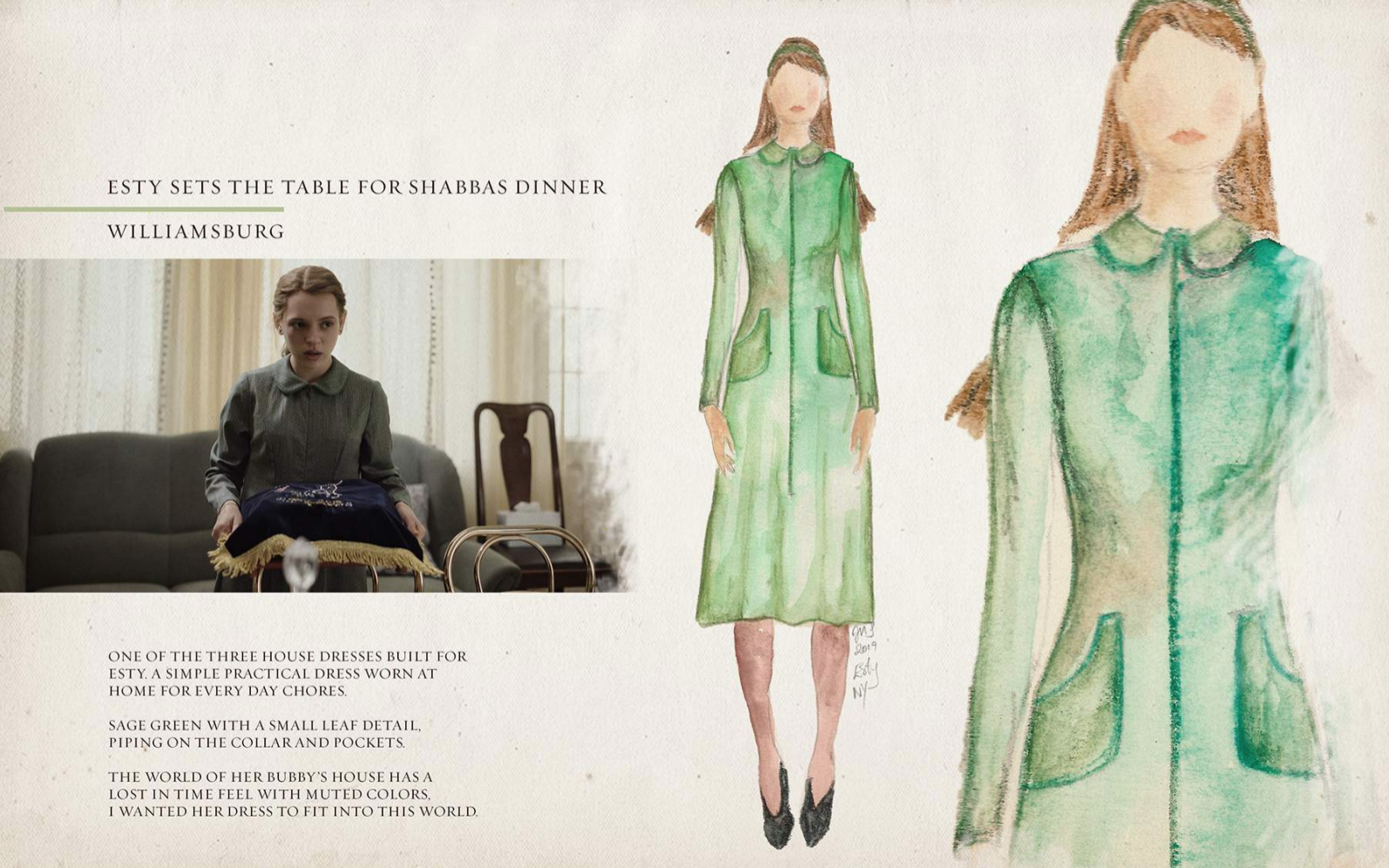

Once hired by director Maria Schrader, Justine’s first task was a research trip to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where some 320,000 Satmar Jews live in relative isolation. This involved visiting a household to observe rituals in practice and photographing the general public. “I did try to speak to a few people on the street”, Justine explains, “but not many were open to talking to me, and the men would cast their eyes away” — a requirement of religious deference. “I’m a very tall English chick who wears red lipstick, so I did stick out like a sore thumb.”

“The trip, though, was essential to conveying Deborah’s story,” she adds. Her work following the research takes Esty on a “visual story arch” from the muted colours and confinement of her modesty clothing in New York to a wardrobe of colour, texture and movement in Berlin. At its most stark, this arch sees Esty in a nightclub sporting red lipstick, gold hoops and an accidentally trendy shaved crop.

In reality, the aesthetic transition was a gradual one for Feldman, who spent three years carefully plotting her escape from the Satmar community. “[Deborah] said it took a long time for her to acclimatise and try new clothing, but I was tasked with communicating that over four episodes,” Justine says. “I did keep [Esty] reasonably modest at first… opening up her neckline just a little bit and shortening the sleeves.” Opting for comfortable shoes over trainers also helped to slow the pace — “I kept one little foot back in the old world, as she crept into the new one”, she explains.

Even when Esty tentatively tries on her first pair of jeans — a moment which “Deborah said that really was quite magical for her” — Justine didn’t want her to leave the shop wearing them: “I wanted her to not quite dare at that point.” The resulting scene is one of the show’s most poignant, marking the protagonist’s departure from the community in the same way that Esty’s wedding dress signifies her arrival.

“It’s an incredibly important step in a woman’s life, to find your husband and start God’s work”, explains Justine — a reference to the responsibility placed on Satmar women to replenish those lost during the Holocaust. She therefore wanted the dress “to speak volumes, literally, about how excited and happy [Esty] was”, knowing marriage would please the community.

“I was looking for a dress that was every little girl’s fantasy, but also ticked all the modesty boxes”, Justine reasons. Budget restrictions prevented her from creating it from scratch, so she sourced the dress from eBay. “We bought it, cut it all up and reshaped the bodice so it was really tight and restrictive, giving the idea that Esty is very much kept within this framework”, a metaphor for her future married life.

As for those headpieces, Justine took a slight liberty in design. Whereas veils and shrouds are traditionally worn during orthodox wedding ceremonies, the beautiful turban-like headdress is not. “To me, it harks back to my childhood and a fascination with Swan Lake. All those lovely romantic notions of my own ideas went into that headdress,” she says. Encrusted with pearls and built by Justine herself, the headdress is her favourite piece in the show. But it’s actually Miriam, Esty’s mother-in-law, who Justine enjoyed dressing the most. A wealthy and intimidating matriarch, Miriam was given extra flair, with Justine using silks, designerwear and a subtle colourway to find “the elegance within the confines of modesty clothing”. The character is juxtaposed with Esty’s aunt Malka, who — as a “motherly, butterly, busybody” — was dressed in ruffles and comparatively bold colours.

Distinctions in costume were also used to emphasise the gulf between Esty’s conformist husband Yanky — dressed in structured orthodox clothing — and the community’s bad boy, Moishe, played by the ex-Satmar actor Jeff Wilbush. “When Jeff came in for his fitting, he was very opinionated about what he wanted to wear,” Justine explains. “He wanted to look more like the Rabbi.” Justine outlined an image of “schlunky casualness”, with suede boots and a navy blue suit. “As soon as I started painting him as the one sexy guy in the show”, she giggles, “he was putty in my hands.”

Although crucial, a designer’s central role in shaping characterisation is often hidden. “A lot of work has gone into the wardrobe before I actually get to meet the actor,” says Justine. She’s also candid about the benefit designers gain from behind-the-scenes spin-offs like Making Unorthodox. Written and directed by Justine’s daughter, the 20-minute feature film goes someway towards conveying how a show like Unorthodox is produced, although “not necessarily the crazy hard work” that’s involved, Justine tells me.

Some of this boiled down to the scale and logistics of the task at hand, but undoubtedly Justine’s perfectionism played a part: “I’m a Hollywood designer, so nothing was compromised.” She’s inventive, too. In the absence of an ageing department (a team that dyes white fabric, converting it to a shade that the camera can focus on), Justine dipped every single white garment in tea in her bath.

Her biggest challenge, though, was building 45 shtreimels, the traditional mink-fur hats worn by married men in the Hasidic community. The costume houses of Berlin proved fruitless and Justine was reluctant to contribute to the fur industry (a decision praised by PETA). After scouring for faux fur samples worldwide, her milliners finally found the right texture, although the moulding still required industrial-strength hairspray: “the type used in the 70s when women were doing beehives”.

Treading that line between sensitively portraying the community on the one hand, and, on the other, giving credence to Deborah Feldman’s story must have been challenging. “That was really at the forefront of my mind”, admits Justine. “But as a designer, there is no judgement. It’s merely observation and recreation”.