Punk is celebrating its birthday this year and, forty years after movement first shook the world in a no-qualifications-necessary fury of V-signs and bondage pants, its originators are being remembered in a series of happenings backed by the decidedly un-punk British Library and Heritage Lottery Fund. Ever get the feeling you’ve been sanitized?

Thankfully, there are a few events offering an alternative to the well-trodden punk path: a film festival at the BFI by musician and filmmaker Don Letts has been nicely curated, as was the annual Stoke Newington Literary Festival (complete with “coolest librarian in the world,” former Buzzcocks manager Richard Boon). Now an upcoming photography exhibition aims to shine a light on one of punk’s more interesting tentacular reaches: Japan.

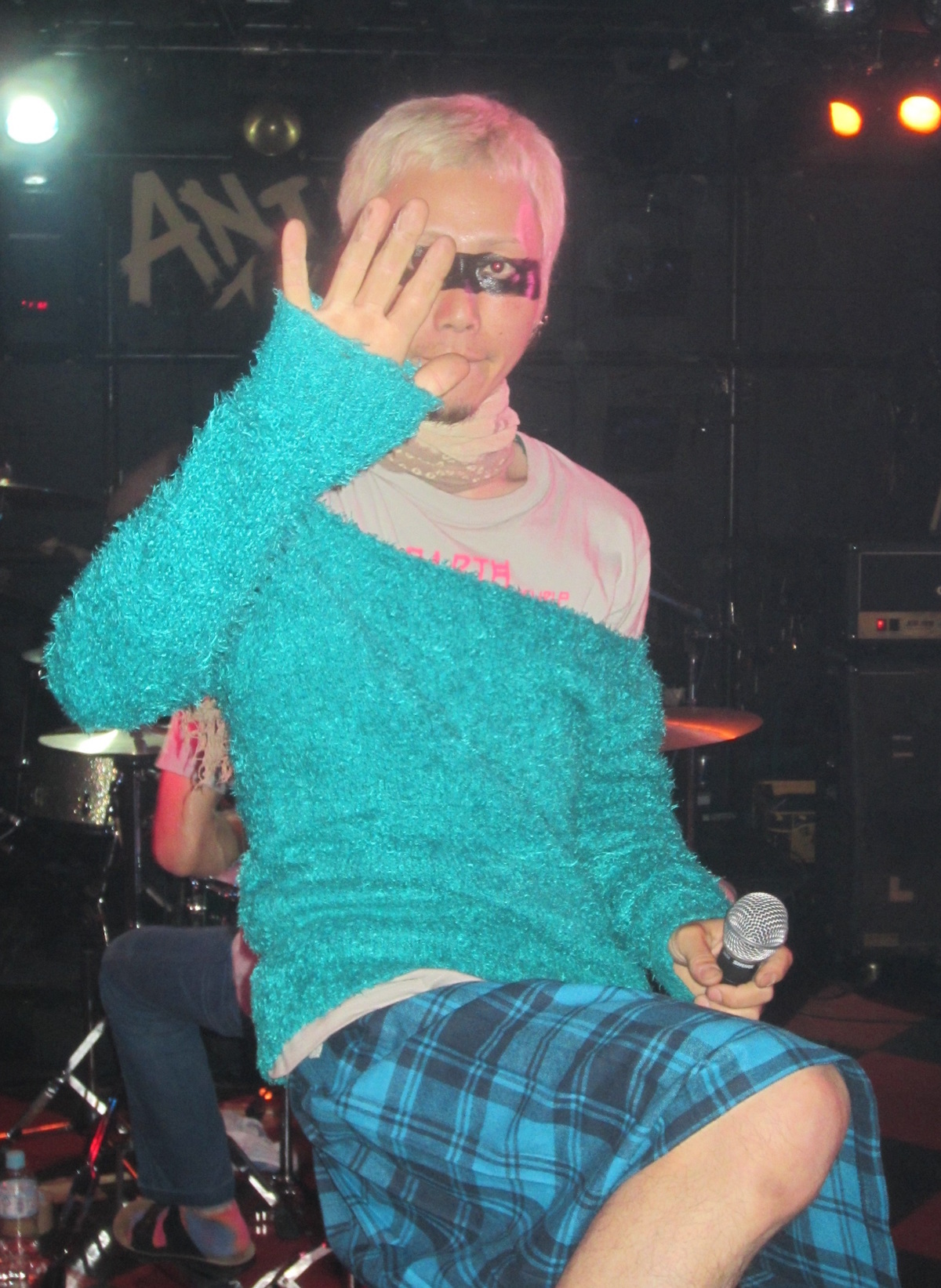

Capturing the five years that photographer and former punk drummer Chris Low spent immersed in Tokyo’s underground scene, Up Yours! Tokyo Punk and Japanarchy Today is a thrilling document of the gigging, partying, shopping, and clubbing infrastructure that has emerged in accordance with punk’s original DIY ethic: Run by Punks, For Punks.

Rather than merely aping the lifestyles of their British or American counterparts, Japanese rockers took the reference points of the Western idols — UK82 mohicans and studded jackets — and made them harder, faster, taller, more studded. Sure, a Japanese punk is using the style to handle very different sociocultural issues than the original, British version. But isn’t that something to be celebrated? And won’t the recontextualization cause it to mutate into something potentially more interesting in the process? With an exhibition of his images opening at London’s Red Gallery this week, we spoke to Chris to find out.

How did you first become aware of Japan’s punk scene?

It’s something I’d always been aware of since the early ’80s since reading “Japan scene reports” in Maximum Rock N Roll fanzine. Back then the idea of visiting Japan seemed about as remote as visiting Mars — which I suppose was a large part of the allure and made it seem so exotic and other-worldly. I first went there in 2002 when The Parkinsons, a Portuguese band who I was drumming for, were booked to play Fuji Festival and a few other gigs. To be honest I was never one of those ‘Nipponophile’ Japanese obsessed types — I’ve never read a manga comic in my life, watched an anime film, or played a computer game — but I really fell in love with Tokyo as a city and have stayed there and visited over thirty times since. My real introduction to the Tokyo punk scene was quite fortuitous, really. I was out in Shinjuku one day when I bumped into members of GBH who were touring Japan. They invited me along to their gig that night and there I met many of the Tokyo punks who since then have become good friends and are featured in the exhibition.

When did punk first find an audience in Japan?

Pretty much the same time as punk took off in other countries following the first news reports and records finding their way out of the UK. I’ve got copies of Japanese fashion mags from early 1978 with features on ‘punk style’ which is an indication of how, by that time, the movement and look had already started to be assimilated into mainstream culture. Thinking of those iconic early photos of punks at The Roxy Club and on the Kings Road in 1976-77, it’s understandable why it was embraced by Japanese youth. Perhaps as a reaction to how outwardly conservative, traditionalist, and perhaps even stifling much of Japanese culture is; when it comes to youth culture, they seem to push everything they pursue to its extreme — whether it’s the music or appearance. The first Japanese punk band, ‘SS’ who started out in 1977 played at a ferocity and speed which left any Western band standing. In fact they were much closer to the ‘hardcore’ sound that would first emerge from the USA a good few years later than any of the UK bands at the time who were still playing speeded up pub rock. Following that sonically frenetic template bands like The Stalin, Lip Cream & GISM also formed and, through reports filtering out through fanzines and the underground tape-trading scene, came to Western attention. As much for their look as their sound.

How would you characterize the look?

While UK punk dress fairly quickly became the uniform leather jacket, bondage trousers and spiky hair, you just have to look at grainy old YouTube clips of bands such as Death Side or Gas to see the look in extremis — with gravity defying two foot mohicans and liberty spikes that make most Western punks look like bank managers, even though the stylistic reference points, in particular the ‘UK82’ studded jackets and spiked hair, are the same. Conversely, you just have to look at the Ganguro or Kogal orange-tan and panda eyes look that was a massive mainstream female youth culture for years to see this extremity in appearance isn’t just the preserve of punks but schoolgirls, too.

How does that tally with the perception of Japan as quite a conservative society? Are its practitioners regarded as outsiders in that sense?

The one thing you come to realize the more time you spend there is that while Japanese society may have the outward appearance of being conservative, in many ways it’s infinitely more extreme and unconstrained than the West. Obviously it’s the unbridled attitude to sex and its representation in any and every form that is most obvious and best known, but the same envelope-pushing attitude can be found in the more areas you encounter — whether it’s the salaryman’s post-work drinks lasting all night and ending with them collapsed, vomiting in the street or their extreme right groups marching about in fascist uniforms carrying swastika flags. Once you get past the formality of the bows the breaks are well and truly off. Punks in Japan are outsiders and are viewed either antagonistically by the police and authorities or as a curiosity by more those of a more liberal outlook. As there isn’t a benefits system like in Britain and begging is illegal, many punks I know work in construction or in factories where their appearance isn’t an issue. Punk for them is a way of life with its own belief system as well as musical tastes. And it’s as much a culture of opposition to commerciality within the punk scene as it is to mainstream society which is what keeps it underground and vital.

How welcomed were you as an outsider?

The Tokyo punk scene I’ve encountered is probably the most friendly, open, and inclusive of any I’ve ever known. I suppose I had a degree of cachet as I’ve drummed for a load of bands like Political Asylum, The Apostles, Oi Polloi, and Part1 and they’re all popular within the Japanese punk scene but I’m sure even if I hadn’t I’d have been treated in exactly the same way, being invited out to gigs and parties and generally treated with a cordiality that is sometimes amiss in the West if you don’t dress the part. I haven’t really dressed punk since the early ’80s as I always thought it was more about the attitude than anything else. In contrast to the rather drab, crusty look of most Western punks now the Tokyo punks look features incredible attention to period detail and the whole “language of style,” which never fails to amaze me.

What’s the infrastructure of the scene like? Is it very active?

One unique characteristic of the scene there is that it isn’t blighted by the factionalism that’s permeated punk scenes throughout other parts of the world. It’s also particularly amazing in that because Tokyo is such a metropolis a vast alternative world of punk run venues, shops, bars and restaurants has emerged around the scene. The punk movement in Tokyo is about a lot more than just the music. In terms of political activism, all the punks I know are very active in combating and protesting against the rise of the Nationalist extreme right in Tokyo, who really seem to have increased their profile under Shinzo Abe’s government. They’re also active in anti-nuclear protests, particularly in the wake of Fukushima, which punks have raised a lot of relief money for as well as campaigning against nuclear power and the recent military expansion in Japan.

How is Japanese punk regarded within the community worldwide? Has it had much of an influence on Western bands?

An absolutely enormous influence, whether most Western bands even realize it or not. The punk sound of today owes more to speed and thrash metal and grindcore than it does to the 1977 punk or even the 1980s anarcho-punk sound of Crass. As my old friend, original vocalist and founding member of Napalm Death, Nicholas Bullen, acknowledges in the piece he wrote for my show by the mid 1980s: groups across the UK were energized and inspired by the vivacity of the often metal-inflected sound of Japanese hardcore, including Napalm Death who were particularly inspired by the urgency and guttural growling of the vocalists in seminal Japanese acts GISM and Kuro. With bands like GISM, Gauze, and Death Side reforming I can imagine a lot of people will be discovering the scene now and wanting to learn more about it. Like much of Japanese culture, Japanese punk is something that is almost fetishized in the West with certain legendary bands fixated upon. While many of those bands are featured in my photos I also wanted to give recognition to the newer and less well known bands as they’re just as important and the ones giving the scene its momentum today.

Are there any elements of the scene that are unique to Japan?

Yes! It was noticing how so many of those I took photos of flicked the V-sign at the camera that gave me the inspiration for the title of the show. It’s something you don’t really see in Britain any more as it’s been replaced by the transatlantic middle finger. I don’t know if they adopted it from being brought up on iconic old Sex Pistols photos but it’s something I find quite archaic and endearing, in contrast to how aggressive it’s meant to appear.

What does Japanese punk mean to you?

How punk should be: run by punks, for punks.

Up Yours! Tokyo Punk and Japanarchy Today is on at London’s Red Gallery from August 18 – 28.

Credits

Text Matthew Whitehouse

Photography Chris Low