This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Post Truth Truth Issue, no. 357, Autumn 2019. Order your copy here.

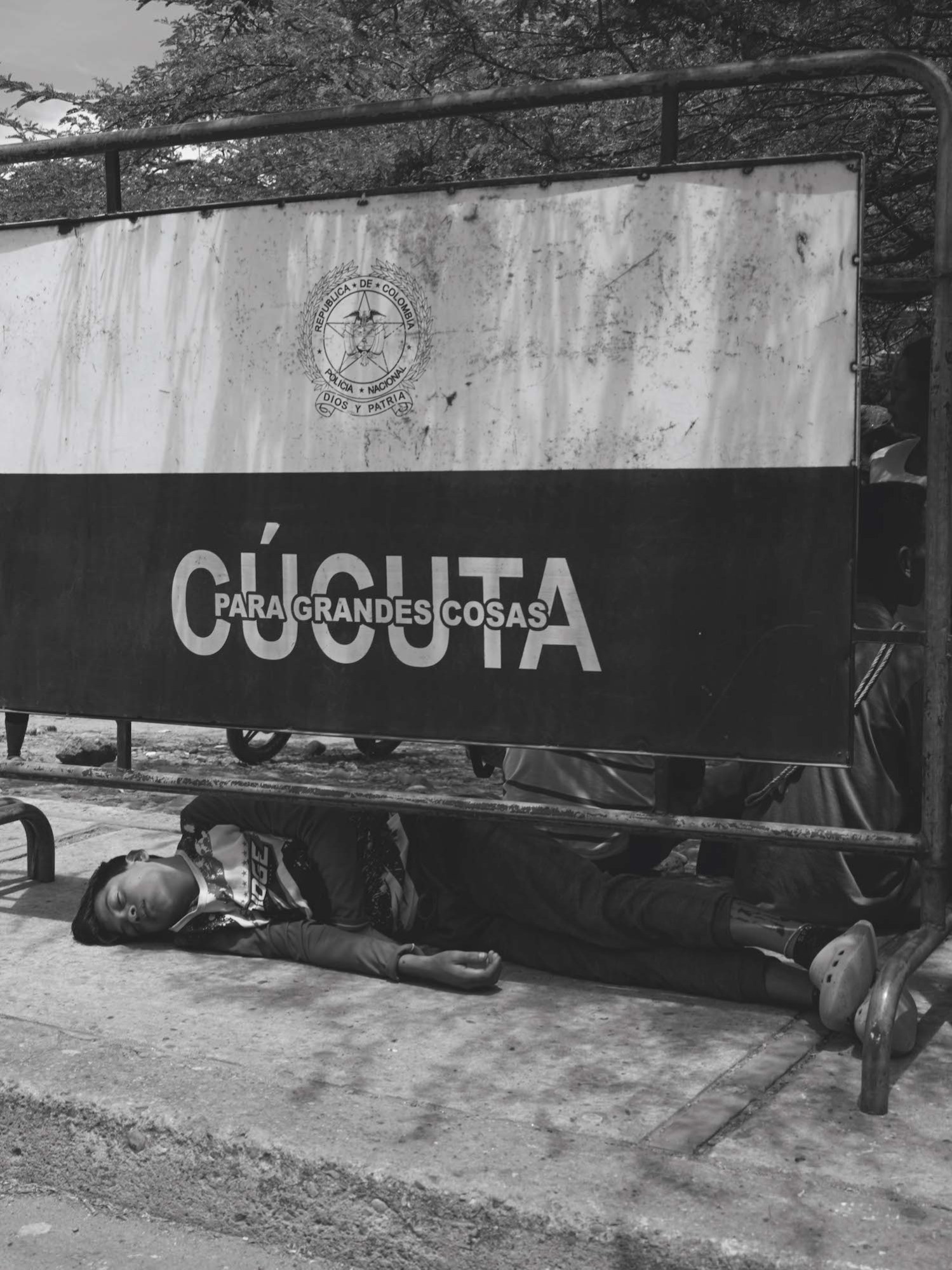

The path out of Venezuela begins at the city of Cúcuta, on the border with Colombia. Equipped with a backpack and fuelled by fear (and some hope), these migrants set into motion something that will indelibly transform their lives. For some, with no specific destination in mind, it’s simply a matter of escape. For others, although sharing the same urgency, there’s some solace in knowing that someone is waiting for them somewhere.

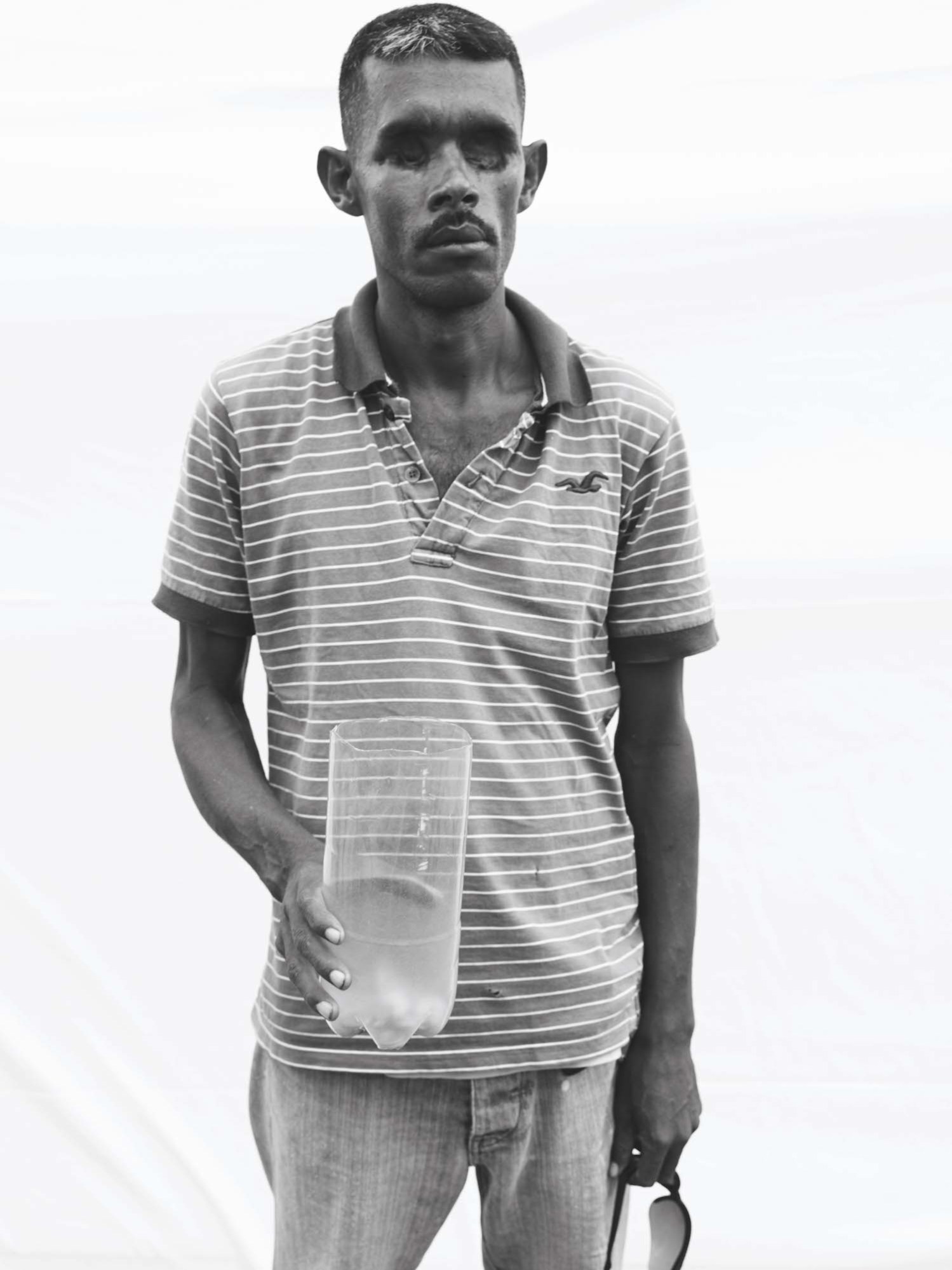

Many of these Venezuelans are without a passport so they have no choice but to enter Colombia illegally: for $3- $6 US dollars you can buy passage across the Táchira River. The crossing is controlled by criminals and paramilitary forces, and the migrants are always at risk of being robbed. There’s also the constant fear of being deported, which instills a sentiment of despair that weighs heavily on their minds; somehow they carry on. The majority of these migrants have no choice but to walk, unable to afford bus fare and without the necessary paperwork.

That walking trail begins at La Parada, a frontier town south of Cúcuta that mostly depends on contraband to keep its micro-economy moving – anything and everything can be bought and sold here. Approximately 35,000 people enter Colombia through Cúcuta daily, mostly Venezuelans in search of food and medicine that isn’t available at home. Many come to work at the border as well, as street vendors and porters. The symbiotic relationship between these Colombian and Venezuelan neighbors has taken different shapes over the decades. Before the crisis it was rare to find Venezuelans working there, as they were primarily the consumers – now they’re competing with locals to get what they can.

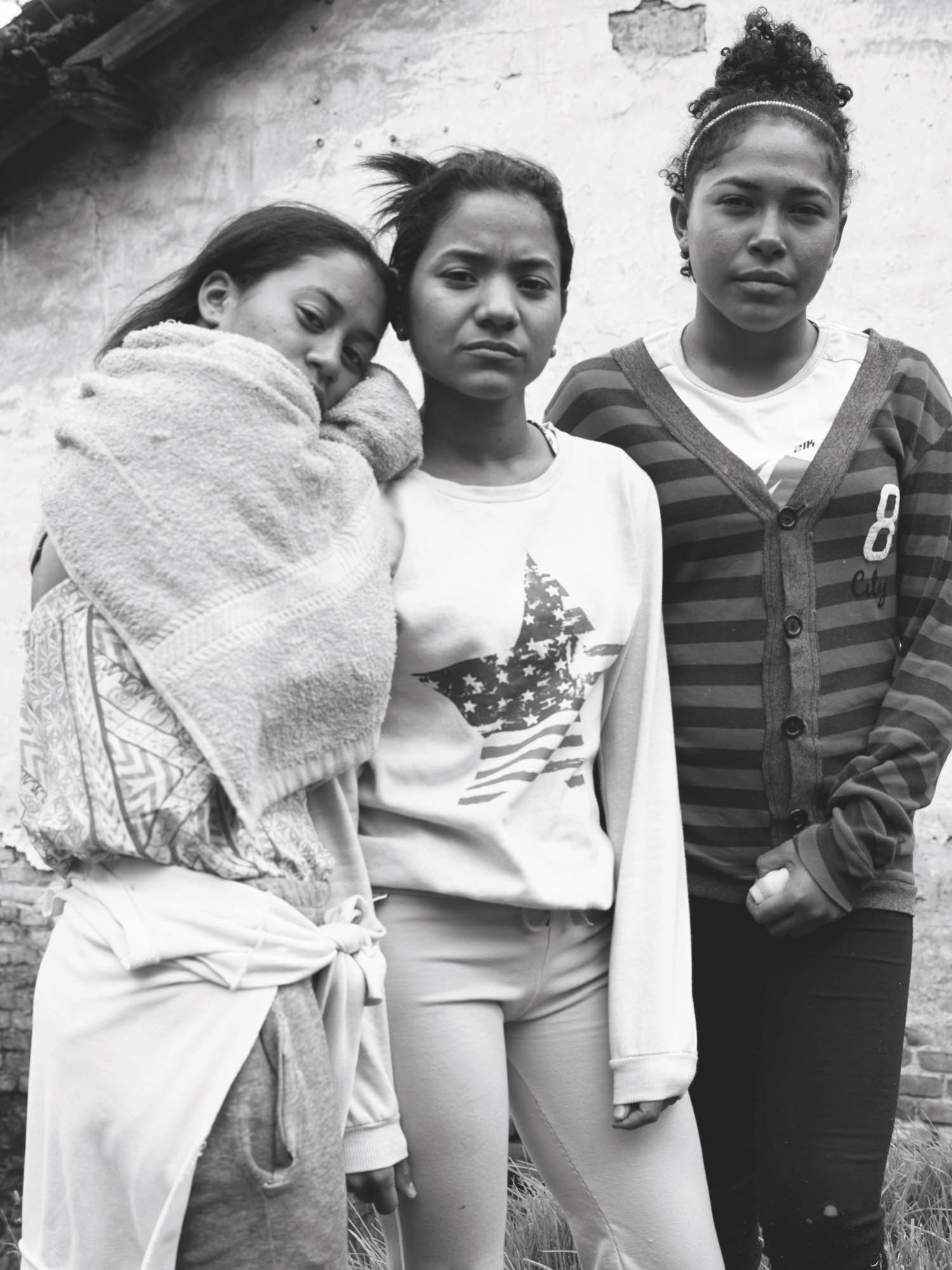

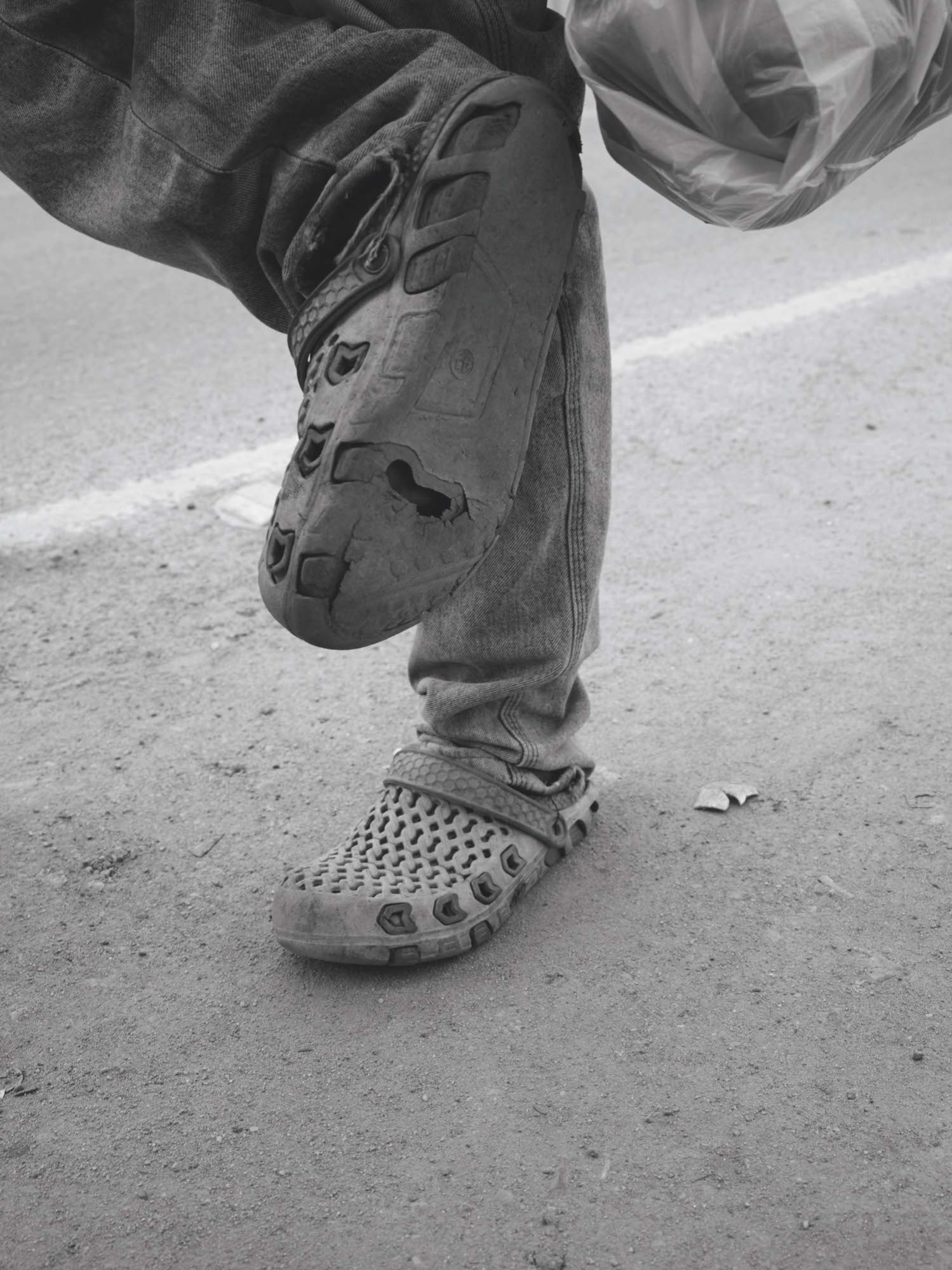

Yet, not all Venezuelans return home from working in La Parada, roughly 5,000 a day are escaping the economic crisis in the country. Pushed to the point where they have to leave their homes, they start their perilous and hopeful path towards a better life. They’re greeted with a sloping ascent into the mountains, less than 50 miles from the border along seemingly endless switchback roads – La Parada is 1400ft above sea level but the highest point up the road is 10,800ft – and many are ill-prepared for the cold weather at higher altitudes. Their rubber sandals start to give out and many suffer along the road, exposed to the wind and rain; the fortunate ones find overnight shelter in the scattered refugee centres along the route.

In these moments of despair you also see the duality of humanity, people at their best and their worst – flesh and blood doesn’t mean much when you’re struggling to stay alive. Helpless kin are left to fend for themselves, robbed of what little they have left; wives and mothers fall into prostitution just so they can provide for their children along the way.

But there’s hope here too. Marta Duque of Pamplona, Colombia, lives in a house by the road that migrants take as they enter the town. After watching so many vulnerable faces pass her by door, she felt obliged to help and opened her home to those passing by, providing shelter for up to 60 women and children a night (the men sleep next door at a separate refugee centre). I was in awe of her makeshift operation – working with a tight-knit crew of volunteers, Marta feeds, clothes and counsels those who pass by. Managing whichever way she can, her unwavering aid has provided for those truly in need.

While crossing the towering El Páramo de Berlin – upon leaving Pamplona – the migrants’ path is framed by a backdrop of perpetual fog resting on the Andean mountain range, a majestic sight marred by the reality of their displacement. It can take up to four days of walking across the moors before they arrive at the next city – this is just the start. Many keep walking and it takes up to two weeks to get to Bogota, Cali or the Ecuadorian border.

Despite the unbearable hardships they’ve faced along their journey, many of the people I met and spoke to were gracious enough to open up and share their stories, to tell their tales and laugh at their own problems. They’ve taught me true resilience and the weight of their collective plight is difficult to put into words, and my words could never do these people the justice they deserve.

Nevertheless, their voices should be heard. It’s easy to dismiss an anonymous person in need but a human response is something we cannot fall short of. Let’s not turn a blind eye to the suffering of the people of Venezuela. I can list staggering numbers to reinforce the gravity of it but I’ll leave that to the accredited organisations. I can only speak of my first-hand exposure to this ongoing crisis and its tragic consequences.

I couldn’t have done this without the support of Juan A. Zapata, Danny Javier Sanchez and Sergio F. Jaimes. Their unflinching nerve and determination were the driving force through some precarious situations. I’m eternally grateful for their companionship throughout this project.

To learn more about this crisis or to donate: Norwegian Refugee Council, UNHCR – The UN Refugee Agency, and the International Committee of the Red Cross are doing the best work on the ground.

Credits

Photography John Guerrero