This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Earthrise Issue, no. 368, Summer 2022. Order your copy here.

Fashion, ever a neophiliac game, is about the new and next. It changes quicker than the wind, constantly blowing through a cycle of fashion shows, drops, collabs and capsule collections: more, more and even more clothes litter our timelines, feeds, and stores. Trends come and go as fast as the TikTok algorithms that document them, and they may seem like harmless and superficial fun. But when fast-fashion giants make the latest viral whatever-core available for purchase in the blink of an eye, they have a terrible effect on the planet.

As I’m sure you know by now, there are casualties of fashion’s supersonic- tempo rhythms. A constant emphasis on newness can be crippling for the planet, for the people tasked with producing these huge columns of rail fillers, and for the very idea of creativity.

All designers are guilty of recycling ideas. But, these days, even the realm of high fashion – which is supposed to be slower and more contemplative – can often feel like a series of bombastic and sensationalist gimmicks conjured to elicit a symphony of iPhone flashes.

They do little to provide a roadmap for how to live in a world that requires radical changes to the way we acquire new clothes in order to slow down the climate crisis. Right now, fashion accounts for up to ten per cent of global carbon dioxide output (more than international flights and shipping combined, according to the United Nations Environment Programme), and accounting for a fifth of the 300 million tonnes of plastic produced globally each year.

“Ultimately luxury, as a concept, is about rarity. And as the luxury industry becomes increasingly fragmented and diluted by globalism and over-production, it is the rare instances of true auteurship that we remember.”

Yet more clothing is being produced than ever before, with McKinsey and the World Economic Forum estimating that the number of garments produced each year has at least doubled since 2000, only a fraction of which gets recycled (87 per cent of the total fibre input used for clothing is ultimately incinerated or sent to a landfill). And that’s without taking the maddening sense of aesthetic deja-vu into account. Once, when I asked a veteran fashion editor why she had retrained as an architect at the height of her career, she offered a simple explanation: “I had seen every trend and idea go full circle, and I couldn’t bear to witness it all over again.”

Fashion is stuck in a bit of a rut. The constant search for newness feels old, and as a result, the old is what feels intriguingly new. Vintage, upcycled, deadstock, pre-loved — whatever you want to call it — clothes from the past have never felt more modern, and as you will notice from the pages of this magazine, we’re here to celebrate them. That’s because fashion – great fashion, at least – is truly timeless. Not in the way that designers often talk about little black dresses or cashmere sweaters, but in the way that a great piece of antique furniture was probably never made to be disposed of once the tides of taste shifted. Great design is forever, and it only gets better with time. It feels modern to disregard timestamped seasons, because that’s how we all get dressed anyway, pairing our newly-acquired finds with beloved old ones.

Besides, the source is often better than the redesigned derivation, plucked from a secondhand mood board. Scroll through High Fashion Twitter – the online community of fashion fanatics who debate and document every great catwalk moment with a forensic level of research – and you’ll notice that the most ardent clothes junkies are mainly interested in the past. They source the catwalk references behind bygone red carpet appearances, meticulously catalogue pre-internet fashion footage, and they would probably be happier working as curators in a museum than at a fashion magazine.

In fact, they probably all want to work at Artifact in New York, an Aladdin’s Cave of over 5,000 rare designer pieces as of writing. The archive is the brainchild of Hugh Mo and Max Tsiring, who have scoured high and low to source some of the most significant pieces of fashion history from the last thirty years. They’ve bought pieces from a kaleidoscopic mix of people: actors, retired models, underground techno DJs, and even Belgian diamond dealers – each of whom has imbued the clothes with a tapestry of stories. And in turn, they’ve lent to every good stylist and designer you know, keeping the circle of inspiration alive.

“Our archive has its roots in the personal collections of our two founders, so there are a lot of items with long, long histories” explains Dylan Burgoon, Artifact’s showroom coordinator. One of the archive’s first acquisitions was a Helmut Lang SS98 snowy white down-filled parka, notable for its dramatic velcro closure designed to conceal most of the wearer’s face. Nearly a quarter-century later, it couldn’t be more prescient for the protectively wrapped-up and masked times we’ve been living in.

Like a great piece of art, that coat is now priceless. Even though, not that long ago, old clothes would never hold the same monetary value as new ones. Therein lies the biggest shift in values that fashion has seen in recent years. Vintage clothes are now sought after by every stylist, celebrity, and design studio, all of whom rent pieces from Artifact because it’s far cooler to have a piece of history than something off the rack – and far better for the environment. Especially when that aforementioned hound of savvy fashion sleuths are eagerly waiting to point out every reference and rip-off of an archival style. The past has never been so present in deciphering fashion’s future.

In many ways, an archive like Artifact pushes designers to be better, first by offering them the chance to learn from every seam and pattern of fashion masterpieces, but also by acquiring contemporary designers, and setting a bar for how the new should measure up to the old. What’s the criteria? “For newer designs, we also try to keep an eye towards longevity, avoiding trend-chasing and hype cycles,” asserts founder Hugh. “This doesn’t mean that we only want simple basics, but traits that make a piece striking and last for years to come.”

Ultimately luxury, as a concept, is about rarity. And as the luxury industry becomes increasingly fragmented and diluted by globalism and over-production, it is the rare instances of true auteurship that we remember, and that we want to wear again and again, because it bonds us to like-minded obsessives. “Archival fashion epitomises the double geture at the heart of fashion in general: a desire at once for individuality and community,” as Dylan puts it. “There is something very appealing about being able to stand out with a rare and unique prize from the past, but still situating this within a broadly shared and beloved history.”

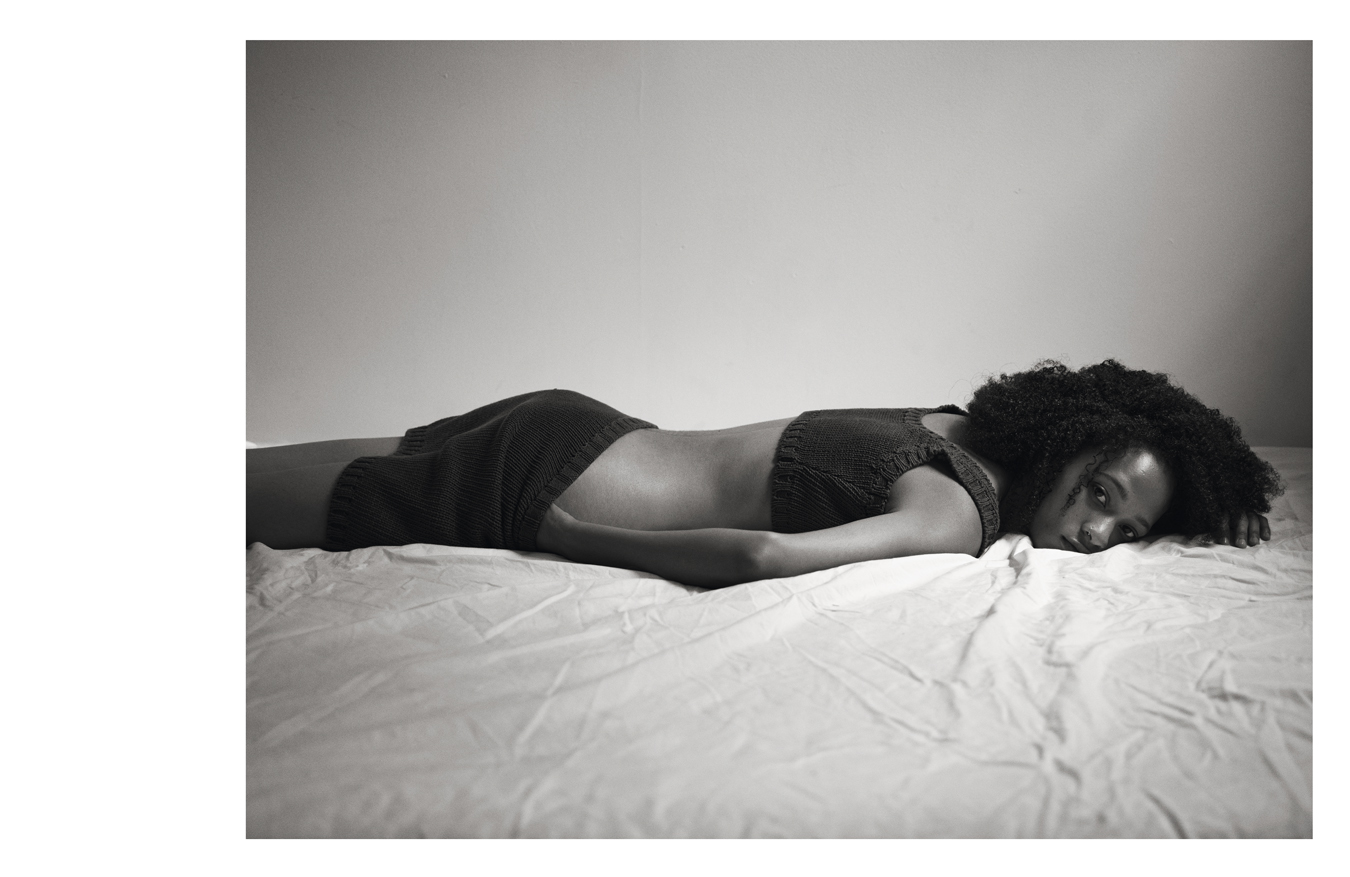

This is why over the following pages, you’ll be simultaneously lusting after (and kicking yourself that you will probably never get your hands on) the clothes worn by Julia Nobis, Selena Forrest and Mica Argañaraz, all sourced from the password-protected digital vaults of Artifact. This is a celebration of some of fashion’s forgotten favourites: whether it’s the Maison Martin Margiela T-shirt reconstructed from deadstock camouflage materials that Vittoria Ceretti pulls off as she winks on our cover, a true emblem of the Belgian designer’s lo-fi upcycled aesthetic. Or, perhaps the domestically- tinged gingham of Comme des Garçons’ AW97 worn by Julia Nobis, a souvenir of a collection that juxtaposed the sweet femininity of gingham with the grotesque, protruding lumps and bumps that dismissed the era’s pervasive sculpted bodies and hyper-glossy aspiration. Each credit reads like a topographical roadmap of a great fashion moment from the last 30 years.

And sure, they’re culturally and historically significant, but don’t they also look so right for right now? Just as with people, great clothes can age well, and the patina of time – a frayed hem here, a stain from a night out there – can be like the elegant wrinkles of wisdom and grace. It’s not what you’re wearing, but the way you wear it. And though most magazines will have you believe otherwise, I’ll let you in on a secret: wearing new-season head-to-toe can often reek of a clinical identity crisis.

Recently, Barbra Streisand appeared on my timeline in a television appearance from 1965. In it, she talks about her love of second-hand clothes: “I buy a lot of things in thrift shops,” she says. “I like second-hand stuff because it has character, and it’s not what a thing costs – it’s what it’s been through.” Now there’s a thought. What if we think of our clothes as mementos of ourselves, sort of like footnotes to the biographies of our lives? In years to come, long after we’re gone, perhaps they’ll still be inspiring generations of fashion-obsessed kids to come.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.