French photographer Violette Franchi first began taking pictures while studying in Kansas. Taking a class on the side of her architecture studies, she soon discovered the two disciplines, in tandem, allowed her to explore a fascination with spaces, and notions of home — in both abstract and structural forms — as well as to “observe local patterns and cultural behaviours,” she says.

More recently, Violette has been studying the Documentary Program at the International Center of Photography in New York, graduating this summer, a course that “completely broke down” what she thought she knew about photography up until that point. “It slowed my approach,” she says. “The first thing I wrote in my notebook back in September was not to just take a photograph, but to make it. The last thing I wrote a couple months ago was to think of our impact as photographers, to think before we show up with our camera somewhere.”

Inspired by the work of Dana Lixenberg and her landmark series Imperial Courts — in which the Dutch photographer documented a heavily neglected public housing project in Los Angeles over the course of two decades — Violette’s Crossroads series takes an expansive look at an area of New York far less known than its more salubrious neighbours. “East New Yorkers have it harder than other places in New York,” she says, “30% of residents live in poverty, with one of the longest commutes. It also recently became the neighbourhood that, to date, has incurred the highest rate of coronavirus-related deaths in the city.”

Coming all the way from France, Violette had a particular image of New York City in mind. “One reduced to Manhattan towers in TV shows, with their countless windows.” But in East New York, many old motels — classic symbols of American culture — have slowly been turned into homeless shelters. “This includes the Oasis Motel, located at the crossing I later photographed. I was curious to see these American symbols and look at their current failures. Walking around that motel and doing research, I understood that two roads separated four parts: a housing complex (Starrett City), New York City’s biggest church (the Christian Cultural Center), a gas station and a shelter. Starrett City, with its forty-six towers and 15,000 residents, is the U.S. nation’s largest federally subsidised apartment complex. The Church, too, was interesting in the story because its current parking lot is soon to become the Urban Village, a massive residential complex, right in front of the homeless shelter. The primary cause of homelessness in the US is the lack of affordable housing. I documented the area right at the end of a cycle: nearly 50 years after Starrett City’s construction, history repeats itself with the Urban Village.”

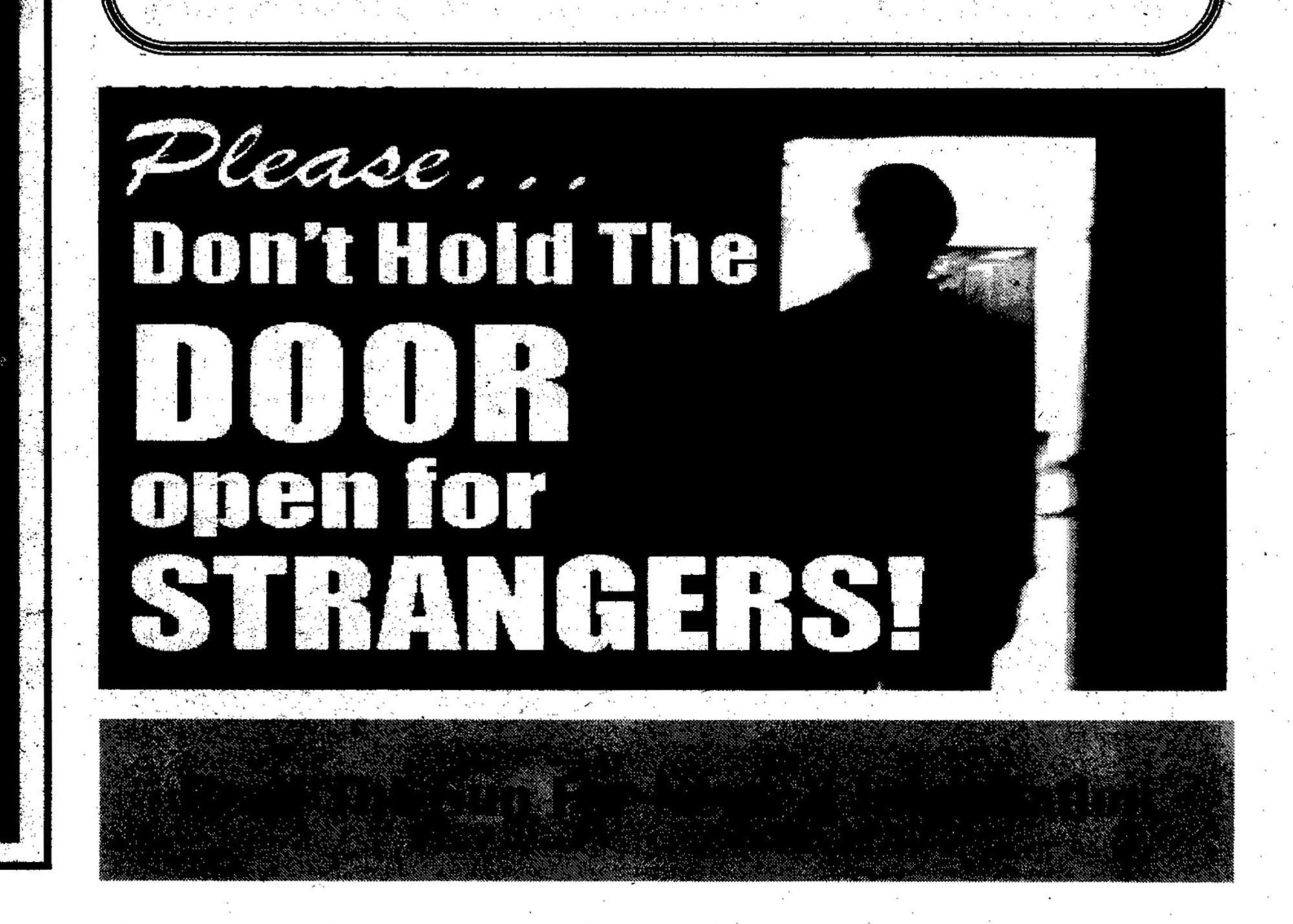

Through housing, Violette wanted to question the American Dream, and whether it is actually accessible to all Americans or not. “Looking through the lens of advertisement made me see the neighbourhood as a commercial product where dreams are sold, so I gathered archival TV commercials for Starrett City, as well as future architecture renderings of the prospective Urban Village. l also started picking up things I encountered while walking the streets: supermarket brochures, discarded newspapers, distributed bibles. These various visuals serve as intentional breaks from the photographs, placed for the viewer to create their own fiction between promises and realities.”

Ultimately, Crossroads gradually became “a story about a place between past and future,” Violette says, “of multiple identities, of realities that never look like they do in commercials, in news reports or in urban plans.”

Credits

All images courtesy Violette Franchi