“I mean, just at look at this,” Virgil Abloh says, pointing at an advert for Hedi Slimane’s new, accentless, Celine. “Editing that logo created an uproar because people believe in logos. I mean, I believe in logos.” And it’s true, logos are very powerful things, and Virgil’s logo is somewhat decentralised but instantly recognisable; Off-White has its stripes, Louis Vuitton its monogram. But more than anything, Virgil is represented by a pair of speech marks enclosing a “WORD” written out in Helvetica –– it is a strategy to cloud meanings and ironise sentiment and, in a way, it is as applicable to what he’s done at Off-White as it is to every creative project he has undertaken. Right now we are in Milan, at the Spazio Maiocchi arts space –– founded by Slam Jam and Carhartt WIP to support the arts and create social gatherings) for the unveiling of his last endeavour, a new art installation he has created.

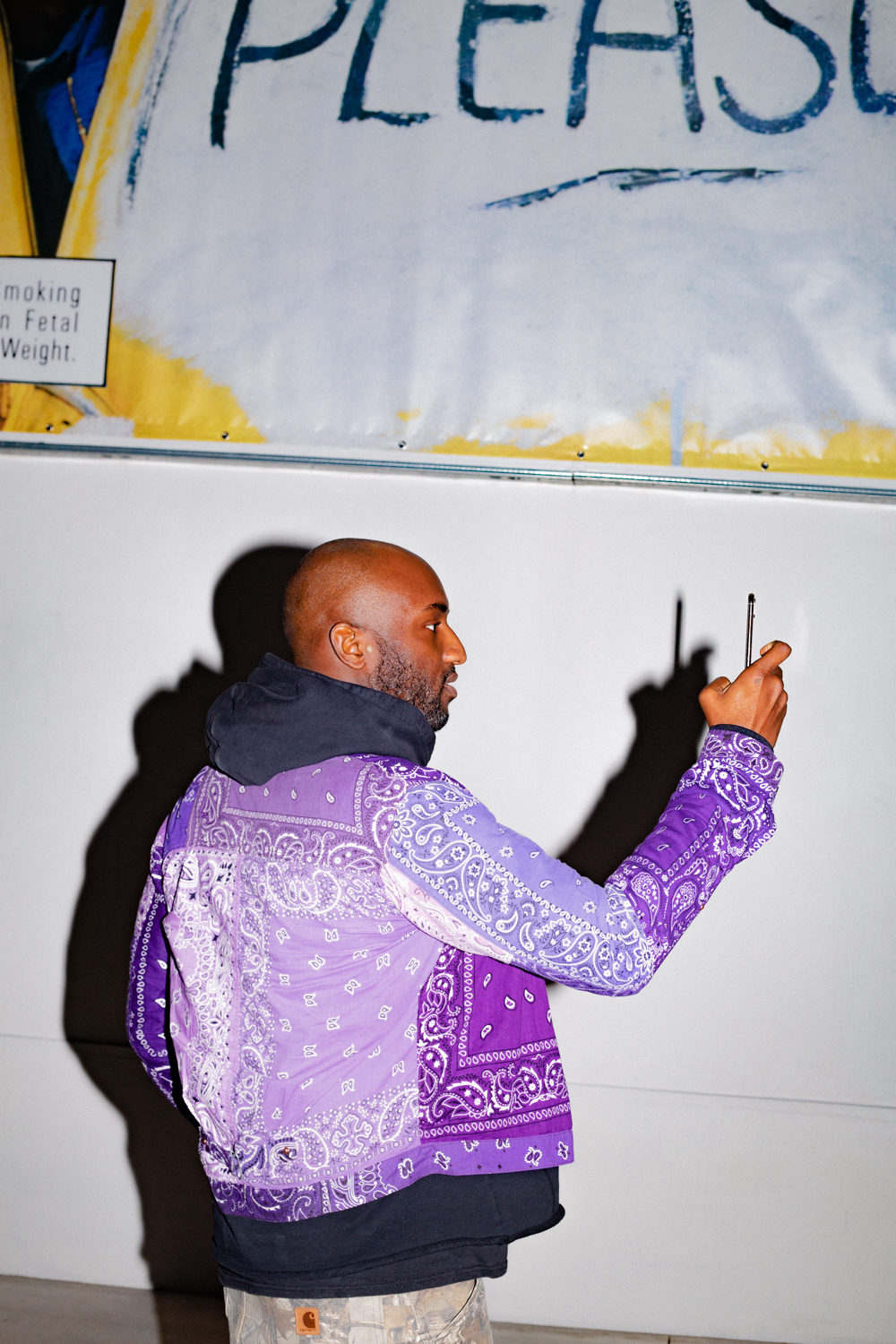

The piece explores the power of the logo and the insidious nature of advertising. Virgil has created a billboard advert for Newport Cigarettes, the image peeling back to reveal a fragment of his own logo, this time reading “QUESTION EVERYTHING”. Virgil has also installed a series of white flags emblazoned with the same slogan over the entrance way to Spazio Maiocchi. Newport cigarettes were infamously and aggressively marketed at African-Americans and Virgil was often subjected to their advertising campaigns growing up in Chicago. The advert he’s recontextualising features a guy leaning out of a snow covered car with “pleasure!” written into the snow on the windscreen. “This image is so mysterious to me,” Virgil explains. “This ‘pleasure’. Newport ads are a Chicago thing I grew up with, black people looking happy and joyful but they’re living in circumstances that don’t look like the adverts.”

Virgil is attuned to the conceptual power that underpins brands and builds systems of value around them –– from cigarettes to sneakers to IKEA furniture –– and has an ability to twist and rethink them and see it from an interesting, new, perspective. It makes what he does so interesting, and has resulted in a dedicated mass of fans who see fashion in the same broad, cultural, creative, terms; who see streetwear as more than an aesthetic but an empowering impetus.

At Spazio Maiocchi he is mobbed by kids, eager to get his signature on their Nike shoes and Off-White T-shirts and the posters and magazines that his face adorns (or not, as the issue of Kaleidoscope he is also here to launch, and of which he is the cover star, has his head obscured by a Vuitton handbag with an eyehole cut into it). “Yeah! It’s weird! It’s weird!” Virgil says of the fans. “It’s the goal, though. It goes back to me being 17. I wanted someone like that to look up to, someone who wasn’t a rap star, who wasn’t a celebrity in that way, but someone who’s work I could connect to and be like ‘oh shit!’” His message is that everyone has the tools to do what he does. He wants to inspire kids to open up Photoshop and get creative. He wants be an example to other young African-American kids who don’t want to be creatively boxed in.

And Virgil has had to fight to get out of that box too. He is famously multi-disciplinary in his creativity –– he’s an architect/graphic designer/fashion designer/DJ/artist –– but his work all blossoms outward from the same root. What he does, especially within fashion, has often led to him being labelled as a disruptor –– but it is a term that comes loaded with the snobbishness of an old fashion elite. Disruptive to whom? Luxury fashion has changed, he hasn’t.

And of course, having now secured a position as the creative director of menswear at Louis Vuitton, Virgil’s approach and sensibilities are basically the norm now. “What I do might be unsettling for somebody else, but you know, I’m dealing with it,” he says. “Imagine if I really believed I was taking ‘fashion’ and turning it on its head. That to me is easy. You can be a disruptor but it doesn’t mean you’re any good. All I’m trying to do is create things are indicative of my surroundings and the community that I come from, so that more people can do them.” That community is “streetwear”, which, for Virgil is an artistic ideology that is more expansive than simply a way of making fashion. It is something that explains his approach to DJing as easily as cohesively as it does his approach to art making.

“Three years ago no one in fashion wanted me to be in fashion. Now I turn up and they’re like, ‘It’s Virgil the famous fashion designer’. But I never made work to get involved in a feedback loop of having someone tell me if it was valid or not. I’m putting what I do on the table, saying this is an expression… To me it’s like a story from a children’s book: I went on a journey to find something and realised the journey was the end result, the most important thing. Art isn’t the object, it’s not about doing something and putting a placard next to it and saying what I’ve made is art. Art is the through line that you can trace back to when I was eight years old and explains how I got here, doing this.”

Virgil’s artistic journey has seen him collaborate and work with a range of Very Well Respected Artists, from Jenny Holzer to Takashi Murakami, but his next step sees him come full circle and step directly into the limelight, as he takes over the MCA in his hometown of Chicago for an exhibition titled “FIGURES OF SPEECH”. He’s been working on it for three years now –– ”Can you imagine me working on one thing for three years!” –– and it is as daunting as it is exciting, a creative process he likens to “wearing glasses for the first time” and suddenly being able to see everything clearly. “It’s an opportunity to express not one single piece of work but the ideology that links everything –– it goes back to the first things I was making in architecture and film, right up to stuff I was making 20 minutes ago. I want to tell the full story, not show fragments.”

The exhibition also marks something of a way-point in Virgil’s career, a chance to expose the mindset in full that led from Virgil in Chicago as a kid to Louis Vuitton. If three years ago no one wanted to take Virgil seriously as a creative fashion force, now he’s showing that creativity in full, coming for the contemporary art world. “A lot of this comes from the angst I have surrounding this preconceived notion I had when I was young about what an artist was. You always carry that around, no matter what, it’s programmed into your brain. I was always looking for validation, and then I realised validation was going to come from me, not from an outside place. This exhibition is the trophy for that way of thinking. It’s like, fuck the art world, fuck the fashion world… I’m in my own place.”