It’s almost the end of 2020 and it feels like the year has simultaneously flown by and lasted a lifetime. Vaccines have begun to be distributed, but we’re far from over the hill. One spending watchdog has forecast less than half the UK population will be vaccinated next year, meanwhile, scientific research suggests that one in five people who contracted coronavirus are likely to develop anxiety, depression or dementia. So it’s perhaps not surprising that people are taking matters into their own hands and turning to alternative therapies, such psychedelics, microdosing, lucid dreaming and, believe or not, astral projection.

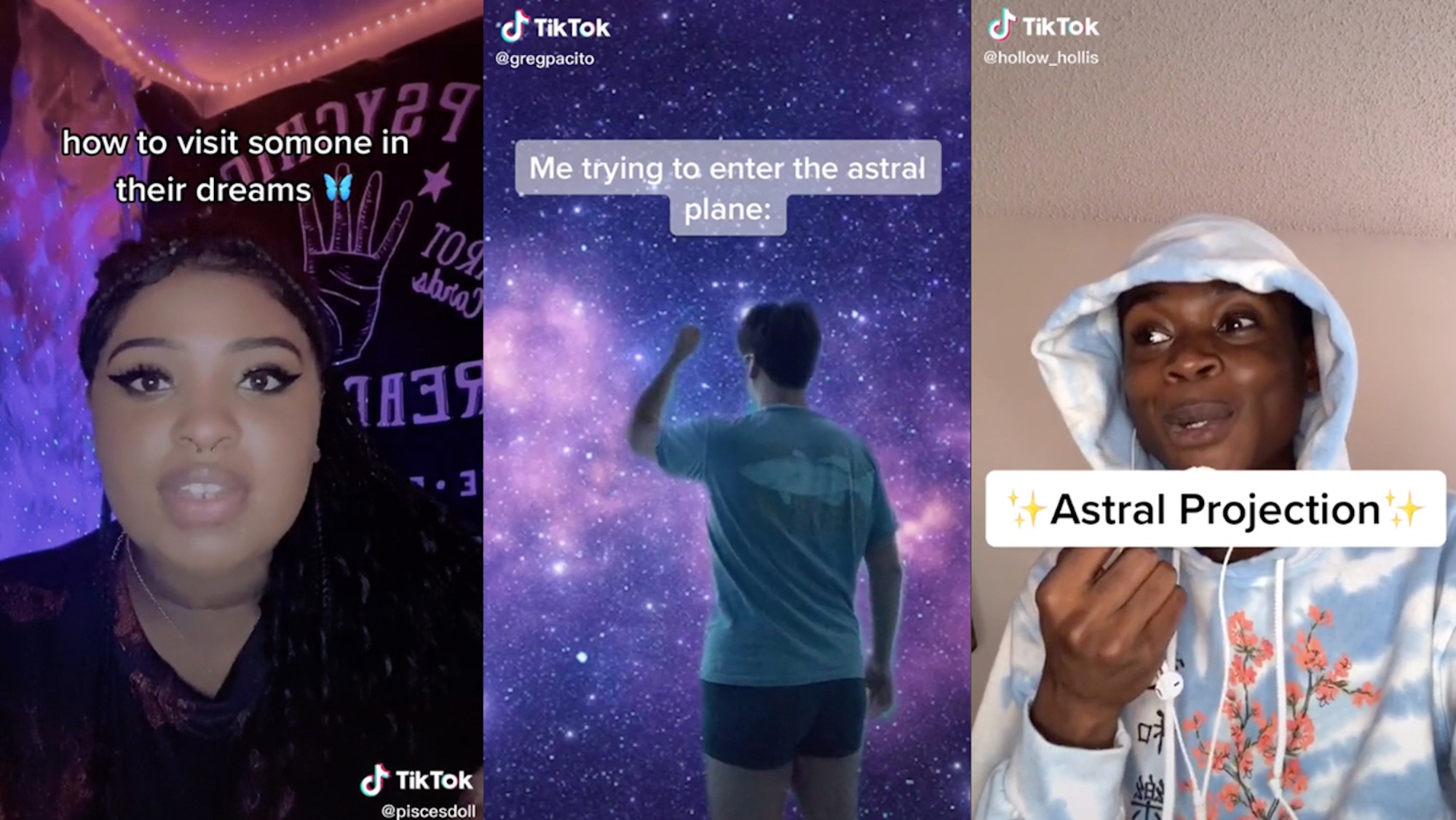

Astral projection is the notion that one can willingly leave your physical body and ‘travel’ to other places, both on Earth and beyond. In a year where travel has been prohibited, and many have felt trapped within their own homes (and in some cases, their own minds) there’s certainly an obvious explanation as to why this concept might appeal. Proponents of astral projection claim that these out-of-body experiences can have profound benefits for wellbeing, reducing anxiety and depression. Just look to the subreddit r/AstralProjection, which has over 160,000 members. Or the hashtag #astralprojection on TikTok, which currently sits at 121 million views.

However, while lucid dreaming — the practise of having control within your own dreams — has long been recognised by the scientific community as valid, and research on microdosing is becoming more mainstream, astral projection is treated with a lot of skepticism and little to no scientific support. Even the name itself is considered by many to be problematic, implying the existence of a ‘soul’ and the idea human consciousness can exist outside of the brain, a highly contentious area of research.

Despite its ancient origins, in recent years the practise has become heavily monetised. Gaia, an online tutorial database for alternative practices, has seen popularity with its video tutorials on astral projection, which can be accessed for $8.99 a month. In the world of astral projection teaching this is a bargain. Some coaches charge around £60 an hour for coaching via Skype, while others charge in the region of £1000 for an online astral projection coaching package.

One person who began looking into astral projection this year is Alice, 30, a digital marketing professional from London, who began learning about it when she was furloughed from her job and was feeling isolated and lonely in her flat. She’s found it to be a positive experience, although she feels that some teachers seem to be taking advantage of people’s boredom and other negative mental states. “There’s no way I’d pay hundreds of pounds to learn astral projection, you can get loads of great books and teach yourself,” she says. Learning astral projection requires patience and commitment, Alice says, describing it as an ongoing process that requires practice.

There are numerous different approaches including meditation, chanting, visualisation techniques, and even sleep deprivation. “I started experimenting with it during the first lockdown, I was really missing being on the beach, so I focused on a memory of a beautiful beach I visited in Thailand. I meditated for about 20 minutes first, then started to imagine my body fading and brought to mind the sensations of the beach, the sand, the breeze, the sound of the sea, and so on. After several times concentrating and focusing, the sensations became more and more real, until I felt like I was really there.”

Even Deborah Hyde, former editor-in-chief of The Skeptic Magazine, the UK’s longest-running publication “offering skeptical analysis of pseudoscience, conspiracy theory and claims of the paranormal” believes that people can benefit from these experiences, but that a level of personal responsibility is needed. “In a sensible world, people should be able to do any ridiculous thing they want,” Deborah says. “The problem comes in when other people are doing ridiculous things to you. You need to be careful about the amount of power you hand over to a person, and it’s the obligation of a person to make sure they’re getting their information from more than one source.” In short, do your homework.

Deborah believes that although out-of-body experiences can be psychologically beneficial, there is currently no evidence to suggest they are verifiably “real” in any physical sense. “Neurologically, they’re very similar to a lucid dream,” she says. “They’re just harder to do, more funky, more marginal.”

Graham Nicholls is an author and specialist in out-of-body research, who has spoken about the subject at Cambridge Union Society — the university’s free speech society — and The Rhine Research Centre — a non-profit parapsychology research centre. At the beginning of lockdown he saw a significant increase in attendance for his online workshops. Graham says anyone can begin to explore this practice but that creative people often tend to find it easier, and a “positive attitude and an exploratory open mind” are vital. He says that people are drawn to astral projection for the way it lets you “experience consciousness in a new way” and for the “direct release of tension and stress” that often accompanies the experience.

Graham believes that logical tests can confirm that these experiences aren’t simply happening inside a person’s head. “In the field of parapsychology, the verifiability of out-of-body experiences is fairly accepted,” Graham says. “The problem is there isn’t enough research, enough data, because there is limited funding for this kind of research and not enough people who are looking into this.”

Deborah, however, disagreed, saying there has been significant interest in this subject by the scientific community. “There’s huge interest in this area because abnormal functions in the brain can teach us a huge amount about how the brain functions normally.” She points towards the largest study ever conducted into near-death experiences by the University of Southampton, which involved 2060 people and sought to determine whether out-of-body experiences were hallucinatory or whether they corresponded with the real world. The study concluded that “while it was not possible to absolutely prove the reality or meaning of patients’ experiences and claims of awareness, it was impossible to disclaim them either” citing that “more work is needed in this area”.

Overall, any proof of the existence of astral projection is anecdotal, and not backed by physical science. But this year has given us plenty of uncertainty to deal with, and it’s easy to understand why people might turn to a practice that seems to offer an escape from a challenging reality. If handled with care and an open mind, astral projection, like meditation or mindfulness, seems to offer those who practice it a different perspective on themselves, the world, and their problems. No, it’s probably not going to transport your conscience to another plane. But like all meditative practises, with research and perseverance, it could offer your mind a much-needed break.