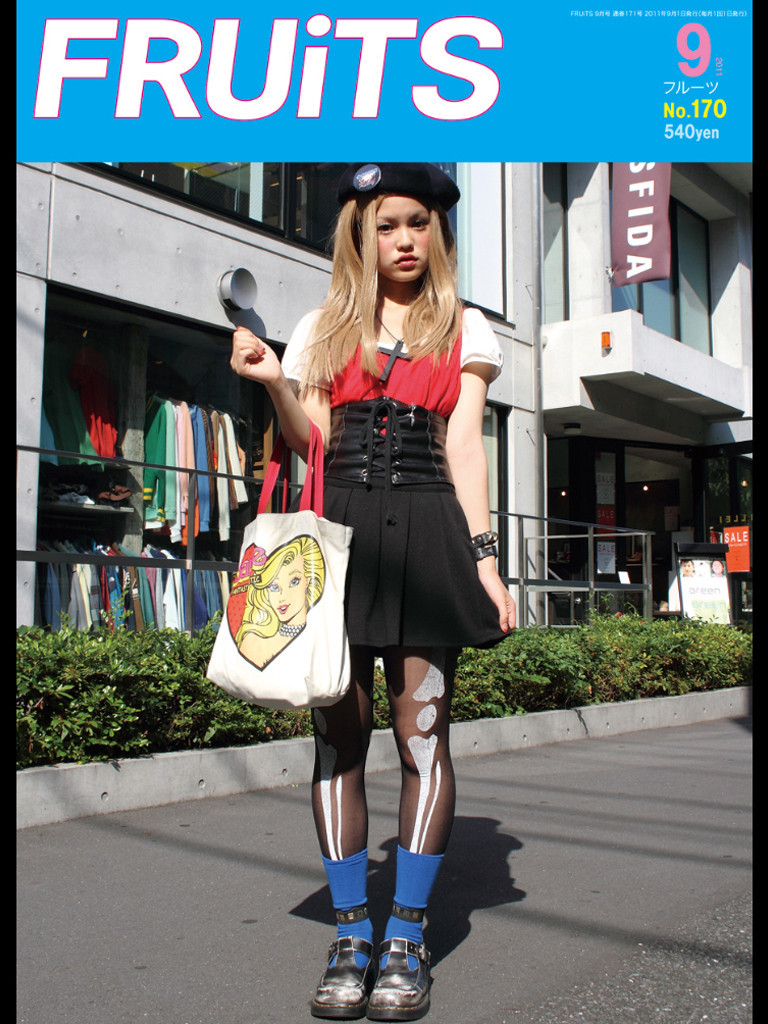

After two decades spent documenting the street style of Japanese teens across an impressive 233 issues, FRUiTS Magazine announced this weekend that it has printed its last copy. While the much-discussed death of print media was perhaps a predictable cause of its demise, the actual reason for the magazine’s closure that its founder, editor, and chief photographer Shoichi Aoki gave was altogether more surprising. In an interview with Japanese site Fashionsnap, he said, simply, that “there are no more cool kids left to photograph.”

Founded in 1997, FRUiTS was the definitive publication that championed Harajuku’s colorfully dressed youth and provided a reliable and authentic record of emerging street trends and genuinely interesting dressers, in contrast to the contrived street style circus of fashion week peacocks. Recognized by its legions of readers as the magazine that introduced them to the saccharine, brave, and frenetic world of Japanese fashion, FRUiTS will be sorely missed by the deserved cult following it has amassed. While fans of the magazine took to social media to decry its loss, some cited the magazine’s insistence on photographing the same kids over and over again as the reason for its failure. Commenting on a news article on Japanese culture site Spoon Tamago, Alan Yamamoto said that FRUiTS had become a “popularity contest,” and that despite the magazine’s closure, “there’s still so much fashion on the streets [in Tokyo] it’s unbelievable.” Misha Janette, founder of Tokyo Fashion Diaries, called the magazine’s loss a “death blow to the already waning Japanese street scene,” and called for more to be done to protect and nurture the area’s style heritage.

The closure of a publication like FRUiTS is a bitter pill to swallow for many longtime fans of Japanese street style, but in many ways its demise has been a long time coming. However tempting it is to wax lyrical about Harajuku’s unique cachet of cool, it’s impossible to deny that the district’s golden age has long passed. Historically regarded as an underground hotbed of street style that most foreign magazines would die to document, the area’s magnetism has been numbed by overexposure and gentrification for quite a while now. The Hokoten pedestrian paradise that provided a nurturing crucible for Harajuku fashion was shut down in the late nineties, and although the area’s girls and boys diffused over the surrounding square mile for the next two decades, things have changed. The reality in 2017 is that if you come to Tokyo hoping to see tribes of teens in the eye-grabbing garms and kawaii Decora that made FRUiTS famous, you’re likely to be disappointed.

The Camden-esque transformation of Harajuku into a souvenir-saturated tourist trap means that instead of the trendsetting locals Gwen Stefani sang about in the early 00s, you’re more likely to see white people dressed in tired Lolita getups haunting the streets. There are still the odd shops like Dog, and 6%DokiDoki hidden close to Takeshita Street that cater to FRUiTS-worthy kids, but they are few and far between, and most of Harajuku now feels decidedly un-Japanese. Although the area has tourism to thank for its success in part, this has ultimately been the cause of its overexposure.

On top of this, Japanese consumers — who have long been known for their preference for quality rather than quantity when it comes to clothing — are falling victim to the fast fashion contagion. Japanese high street heavyweight Uniqlo saw its profits rise by a whopping 45% in the last quarter alone. It’s certainly true that offline street fashion in Tokyo currently pushes a more lo-fi sensibility than it used to, and normcore dressing shows no sign of dissipating. In the past decade, the appearances of monolithic Western imports like Forever 21 and H&M mean cheap clothing has become much more readily available, so it follows that Tokyoites just aren’t spending as much money on the pricier local brands as they once were, and individual style is waning because of it.

Despite the increasing dominance of the high street, and the sentiment Aoki’s statement suggests, Japan isn’t facing an all-out style apocalypse; compared to most fashion capitals, Tokyo is still spoiled when it comes to achingly stylish dressers. In the past, kids paraded down Omotesando intending to get their picture taken, and managing to get into a magazine like FRUiTS was considered a great honor. If that was the case, then where are they now? These days, time spent on self-promotion is better invested online, and the lives of Harajuku’s next generation play out on Instagram.

This means that the authentic outfits of dedicated kids that FRUiTS won fans for snapping don’t orbit around a single area, and are therefore are much harder to come by. Many of the stylish kids who do still work in Harajuku have international internet fanbases, and recent notable trends like Genderless Kei gained traction, above all, for their presence and popularity on social media. While this focus on online outfit PR presents difficulties for street style photographers scouting the well-dressed everyman, it’s also a way for Japanese kids to promote their style on a global level. In many ways, FRUiTS was a predictable if unpreventable casualty.

Outside of independent social media, mainstay Japanese sites like DropTokyo and Tokyo Fashion are still successfully documenting Japanese street style and, although not printed, still authentically showcase the way young people dress there. The sartorial hole left by FRUiTS‘ absence may not be quite as gaping as its grieving fans would have you believe, and while its death is certainly to be lamented, it might better be read as a signal of one area’s inevitable decline rather than the harbinger of a styleless Japan, full stop.

The district is not the street style mecca it once was, and nor does it need to be. That may be cold comfort to the readers fretting over the loss of FRUiTS, but they need only look online to see that inspirational Japanese dressers still exist in droves, and for better or worse, their internet platforms mean that they likely reach a wider audience than any magazine. As for FRUiTS, it will undoubtedly remain unbeaten as the publication that put Harajuku on the fashion map, and provide an invaluable window into history’s most fascinating street style boom.

Credits

Text Ashley Clarke