Six months ago, who would have thought that fashion was worth saving? Protesters picketed fashion shows, customers demanded transparency from brands, and designers began to reject the system altogether, sitting out seasons and upcycling deadstock materials to create limited-edition pieces. Fashion, at least in the traditional sense, had already become deeply unfashionable long before coronavirus rendered it officially démodé. The fashion system as it existed before needed to die in order for the planet – and creativity itself – to survive. And yet, for all the “it has to change” discussions that have been going on for years, change has amounted to little more than formalised frustration as the industry has nonetheless continued to accelerate at breakneck speed. One fashion editor likened it to Mark Twain’s take on atmospheric conditions: “Everybody talks about the weather but nobody does anything about it.”

In February, which feels like years ago now, no one would have thought that the month of fashion shows we witnessed could be the last of its kind, or that we were observing models dressed for a future that would never come. The pandemic showed up at Milan Fashion Week, which began with Campari-appropriate sunshine and the usual sartorial splendour (Silk fringes at Prada! Shearling tassels at Bottega!) and ended with an unprecedented cancellation of the Armani show and a sombre, slightly panicked exodus from the city… if only to Paris. The shows must go on, we decided, and we soldiered on. Except hand-sanitisers were distributed at the entrance to shows; air-kissing avoided; Kanye’s church service was a glorious ocean of socially intimate bodies; and face masks accessorised with Chanel camellias and bijoux brooches were a source of eye-rolling entertainment rather than a prophetic omen. Back then, the conversation on the front row was whether fashion could weather the absence of the all-important Asian market, notably absent from the shows. No one foresaw the global lockdown and terrifying deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

In hindsight, it was the last hurrah, a modern-day counterpart to the Duchess of Richmond’s ball in Brussels on the eve of the Battle of Quatre Bras. In just a few weeks, the world became a different place. The fashion industry is predicted to lose 35% of its independent businesses, 50% of Italian fashion companies and manufacturers are at risk of collapsing, monolithic department stores have gone under, and then there’s the young designers whose orders have been cancelled and careers put on hold. There are the Bangladeshi garment workers who have been left destitute and abandoned by fast-fashion retailers; there are the laid-off factory and mill workers across Europe; the shop assistants furloughed and independent boutiques shuttered; a freelance ecosystem of models, photographers, hair and make-up artists out of work; magazines in even more of a state of flux than usual; and the future of fashion students left unclear without the graduation shows they have spent years preparing for and their lives dreaming about.

Yet fashion’s hardship has been put into perspective by the urgent pleas from frontline medical staff and under- funded healthcare services in need of vital protective clothing and equipment. When governments failed to provide it (almost half of Britain’s doctors have had to source their own PPE according to the BMA) hospitals called upon fashion designers and brands, who answered with urgency and efficiency. Phoebe English, Bethany Williams and Holly Fulton were inundated with requests from hospitals, so they set up the Emergency Designer Network with the help of fashion matriarch Cozette McCreery, an initiative to utilise local makers and manufacturing to supply hospitals with vital protective wear.

Together, they rallied their fellow independent designers and factories – as well as individuals who can sew at home – and provided them with hospital-approved patterns (cut at a facility in Nottingham) which they blueprinted by deconstructing a sample set of scrubs, as well as NHS- certified fabrics from a Lancaster-based supplier. They galvanised big fashion businesses to contribute: Net-a-Porter and Matches have lent their courier vans to get things from A to B; Urban Outfitters and John Smedley have put the might of their factories behind the effort. Everything is made and delivered according to social distancing rules and medical specifications, and as result they’ve become key mediators between healthcare services and a local ecosystem of makers, producing over 5,000 garments at the time of writing. Coincidentally, they launched the initiative on the same day that the government was criticised for being slow to enlist the help of British textile firms.

You would think that they had been doing this for years, not just a few weeks. “The hellish multi-tasking right before a fashion show is perfect training for this kind of moment,” Holly says. Cozette adds: “I think because a lot of us have worked on collaborations, this just became another client. We’re very good at being given briefs and then running with it. People often think fashion people are frivolous, but in fact we like to find solutions to things.” Testament to their ability to immediately mobilise the troops is the bedrock of local manufacturing skills, often overlooked in favour of glitzier distractions (sequins!) and the one-man-show creation myth of omnipotent creative directors. But no fashion label is an island – it has always been a team endeavour. “No one can run a label or produce a collection alone in a shed on the side of a cliff,” Phoebe explains. “We’ve all had small fashion businesses where you have to be a businessperson, a website designer, a social media person, a pattern cutter, a sales manager… But in the end, you have to be constantly collaborating.”

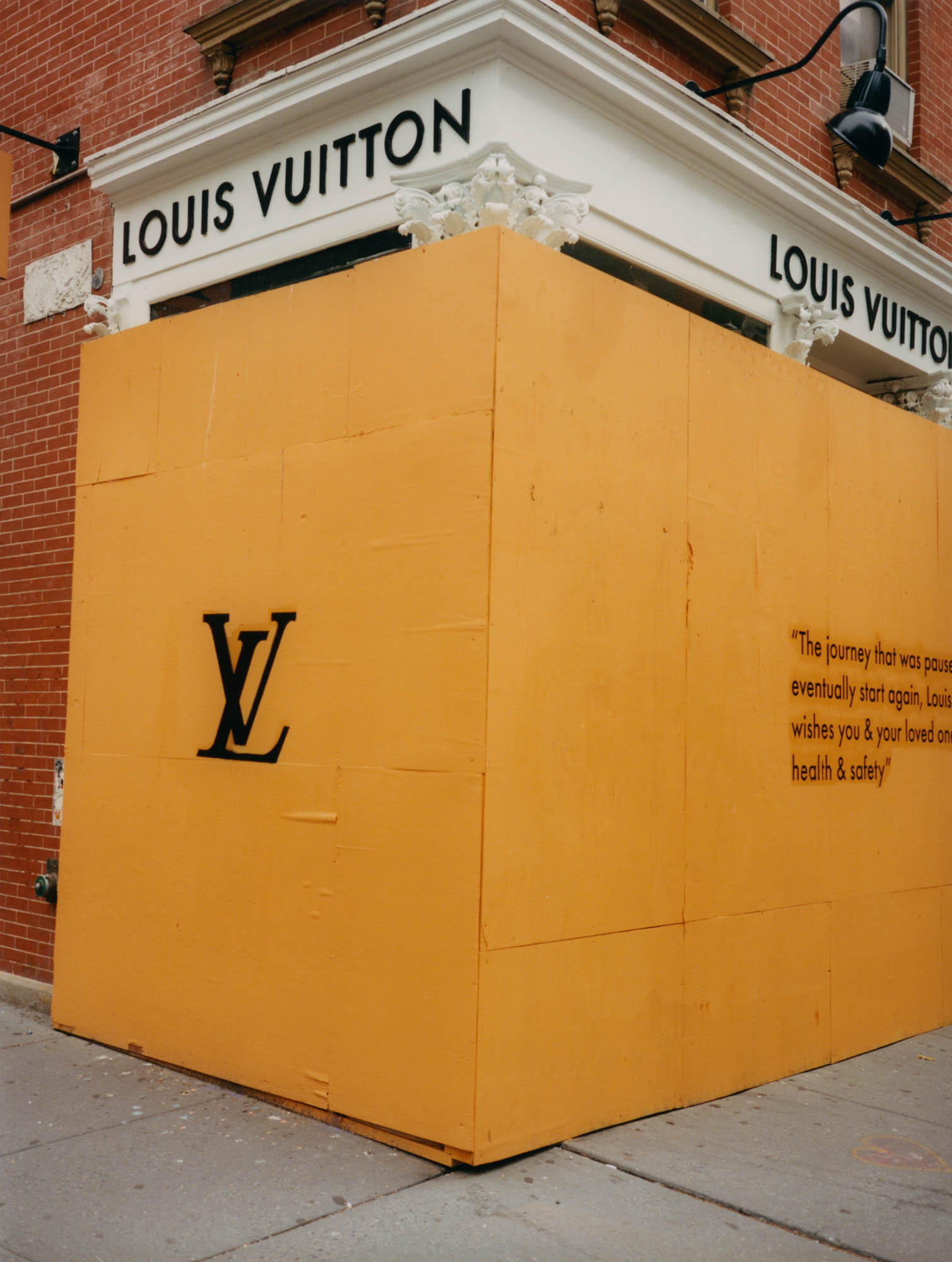

The message is that we’re all in this together. Designers and fashion executives around the world have been casting aside rag-trade rivalry and are desperately sharing information and medical contacts, rallying their artisans and factories to do what they can for global health services. Even fashion prizes, whether it’s the British Fashion Council’s or the LVMH Prize, have split the total winnings among applicants and finalists, making it clear that now is not the time for competition. The pantheon of luxury megabrands has donated millions to ICU units, coronavirus medical research, and repurposed their facilities to make protective masks, gowns, gloves, goggles and caps as a matter of emergency. LVMH and L’Oréal have repurposed factories to produce hand-sanitiser for medical use, Burberry and Gucci to make hospital gowns and medical masks.

And while all of that is truly wonderful, it also begs the question of why it’s taken so long to create such a radical shift in values, especially considering the urgency of the climate crisis. Surely such flexible adaptiveness makes it clear that fashion can also just as quickly reduce its carbon footprint and clean up its environmental vandalism? Then again, if coronavirus has awakened an egalitarian humanitarian spirit among fashion brand executives and a collective morale boost of we-can-do-this energy in designers, it has also highlighted the gaping pitfalls of the fashion system and its worst offenders. Consider for a moment the fast fashion retailers who were quick to publicise their charitable efforts in the fight against the virus at home, and even quicker to cancel their orders with Bangladeshi factories and leave vulnerable garment workers destitute.

Fashion is at a crossroads that it may never come across again. Finally, we have a chance to reconfigure its future and right now, we need to decide where to go as both an industry and consumers. How much of the old normal, which was not really normal at all, do we leave behind? How can we ensure that creativity is protected, garment workers respected and the environment never neglected? Most importantly, what elements of fashion are worth saving?

There’s creativity, of course, which is why we all fell in love with the industry in the first place. But it has slowly been decimated by the unyielding pace of misaligned seasons and an emphasis on heavily branded but expensive and totally nondescript clothes. As boutiques and retailers are bordered up, closed for the foreseeable, a sea of it is flooding the sale sections of e-commerce platforms, which have had to tout massive markdowns on merchandise that no one is willing to buy at full price. Therein lies the problem. “We’re not able to give the product long enough to sell,” reasons Holli Rogers, CEO of Browns Fashion, one of the few retailers that pays young designers upfront for their collections by sponsoring the British Fashion Council’s NewGen scheme. It goes without saying that those designers are disadvantaged by the system. “Considering the price points of what we’re selling, there’s a lot of effort and love and time that’s been put into producing these things and as soon as you put them into markdown, you lose that. A few months is not enough.”

Holli is the first to admit that buyers travel too much, that there are too many shows, too much inventory, that designers get caught in the hamster wheel and it’s near impossible to get off. Ultimately, it takes a toll on creativity. “We see repetitiveness in everybody’s collections,” she says. “There’s so much of the same stuff being produced by everybody and no clear point of view. That’s the one thing in the last set of shows that we were talking about. It felt super flat. There’s nothing interesting right now.” Now that fashion is in a state of flux, she points out there’s hope and an obligation to reconfigure it, adding with a sound of relief: “We don’t all have to sing from the same hymn sheet anymore.”

Even the most seasoned and celebrated creatives have had enough and if fashion was once an impenetrable mountain of mystery, the pandemic has served to shatter the smoke and mirrors with creative directors and supermodels taking to social media to speak to their customers and fans directly and intimately, and as a result, inclusively. “What I do and the clothes that I make and the way we present a show, it feels like that probably will never exist as we know it, the way we did it,” admits Marc Jacobs over a Zoom call, grounded by the low-res pixelation. “We’ve done everything to excess [so] that there is no consumer for all of it, and everybody is exhausted by it. It’s all become a chore that’s just a waste of time and energy, and money and materials. I just think that the whole waste is taking the luxury out of fashion, as well as the creativity out of it, because when you’re on such a tight calendar and you’re just told to ‘produce, produce, produce’. It’s like having a gun to your head and saying, ‘Dance, monkey’. It’s just ridiculous, you know? I think if the system doesn’t change then we’ll change.”

In New York, Anna Wintour and Tom Ford have launched ‘A Common Thread’, to raise money for the many US fashion businesses facing imminent extinction. How many exactly? “Look at the New York schedule – basically all of them,” said a CFDA executive. It has asked the public to donate money, essentially asking society whether it believes fashion is not just a business vital to the economy, and the skills and craftsmanship of its workers intangible assets of heritage, but, also, if it is a cultural asset worth protecting. And the answer is yes, of course. Fashion shows can indeed be points of cultural reference (think of Rick, Galliano, Rei, Demna, Marc, McQueen, Margiela) but they can just as often be anodyne parades of nothingness that rack up considerable impact on the environment. Alexandre de Betak is one of the producers of some of the most memorable shows, and during lockdown he has been focusing on alternative ways to communicate shows for the people who will likely not travel for a while, as well as establishing a manifesto to reduce the carbon footprint of the IRL ones (the travel undertaken by buyers and brands in one year of shows resulted in about 241,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions, according to one report – the equivalent to the annual emissions of a small country or enough energy to light up Times Square for 58 years). “Things will never be the same again and that’s a good thing,” Alexandre says. “Our world needed a change and this has accelerated it in a rough manner. Even when we’re able to be together again, there will never be as many people who come from as far as they did before. People need a better reason to travel for the show, and we need to make a truly digital experience for each one, so that people don’t have to travel,” he adds.

So, perhaps fashion weeks (as we know them) are a thing of the past. Saint Laurent is the first major fashion house to opt out of the cyclone, choosing not to show during Paris Fashion Week come September, even if it does go ahead. “We have known for years that something has to change,” explained Anthony Vaccarello, who reasoned that he shouldn’t have to rush a collection. “The time is now… I want to present a collection when I am ready to show it. Slowing down and living in the moment reveals all the vulnerabilities of an imprisoned organisation. What’s out of fashion now is the schedule of the entire system: the shows, the showrooms, the orders.” The idea is that by slowing down, the craftsmanship and beauty of great fashion will shine more brightly.

Other fashion houses may follow suit over the next few months, and given that menswear and couture weeks have already been cancelled, they will certainly have to find new ways of communicating their collections – that is, if they are able to produce them. The Cruise 2021 ship was due to set sail this May but now its far-flung stops (Gucci in San Francisco, Dior in Puglia, Chanel in Capri, Prada in Tokyo, MaxMara in St Petersburg, Armani in Dubai) have been cancelled indefinitely. It’s strange to think that these brands even marketed the announcement of these destinations as breaking news, often with embargoes – and we bought into it. Perhaps now that ship will be docked forever. The jury is still out on Paris and Milan. London has temporarily switched to a digital, consumer-facing, webinar-style event.

For many in our industry, that’s a bittersweet pill to swallow. Yes, fashion needs to clean up its act, but the prospect of a world without fashion weeks, without all the deliciously frothy dreams of designers and powerful statements about the times we live in – and all the self-expression of the peacocks, eccentrics and tribes ripe for people-watching – seems like a world without colour. Then again, the creative sparks we’ve seen from the fashion community – from designers making medical supplies to creatives coming up with innovative ways of producing spellbinding imagery – is testament to the fact that it will endure no matter what. “Fashion is indestructible,” read the caption of Cecil Beaton’s iconic photograph of a model posed among the debris after a night of devastating bombing in 1941: “You cannot ration a sense of style.”

“We have a responsibility as designers,” affirms Valentino’s Pierpaolo Piccioli from his home in Nettuno, the Italian coastal town where he grew up. “We have a voice, we have to give hope, we have to give lightness, and we have to believe in dreams. I’m always positive: I always feel like there will be light. This is a dark moment and we have to rebalance a lot of things and values. In this moment, I think that we don’t need things, we just need people. We need embraces, we need emotions.”

Who knows what will happen next? Historically every economic downturn has been followed by periods of unbridled excess – from Christian Dior’s New Look in the aftermath of WWII to Christian Lacroix’s brash 80s power shoulders and puffballs after the gloomy, three-day-week 70s. It’s unsurprising that many are sceptical that we’ll just accelerate faster and further and more ferociously, even if everything is pointing the other way. Case in point: Hermès reportedly cashed in $2.7 million at its flagship boutique in Guangzhou’s Taikoo Hui on the first day of trading following an ease of lockdown restrictions in China.

But the fashion world will have to slow down, surely, given that it will be smaller, if only due to natural selection. Though brands and politicians will claim that buying more is vital to make up for lost time and rebuild global economies, such rhetoric should be taken with a big pinch of salt. What we need is less stuff – and more of it to be better. We need to fall in love with fashion again for the right reasons. We need to question the traditional ways of doing things, to share information and local networks and think of sustainability on human, creative and environmental levels. We need to make sure that we can look back at this historic moment and say that we created something positive, that we laid the foundation for much-needed change and a better future in which creativity and craftsmanship are key values.

When does the future begin? As soon as the past ends.