Martin Scorsese, everyone’s favourite Italian-American cineaste, is arguably the most influential film director of the last 50 years. He has single-handedly redefined the capabilities of cinema, birthed countless masterpieces, and made legends of Robert De Niro, Harvey Keitel and his TikTok queen daughter Francesca Scorsese. In recent years, Scorsese’s cultural might has grown to the point that any public murmur of indifference towards superhero IP (he’s shrugged them off a few times now) has been met with pants-pissing fury by people who paid money to see something called Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania. He’s a director who, in his own words, is a teacher first and a filmmaker second. Most importantly though, in the words of his daughter, he is “a certified silly goose.”

With Killers of the Flower Moon having bowed to resounding praise, it’s time to cast an eye back to Scorsese’s earlier works, and what really makes a Martin Scorsese joint.

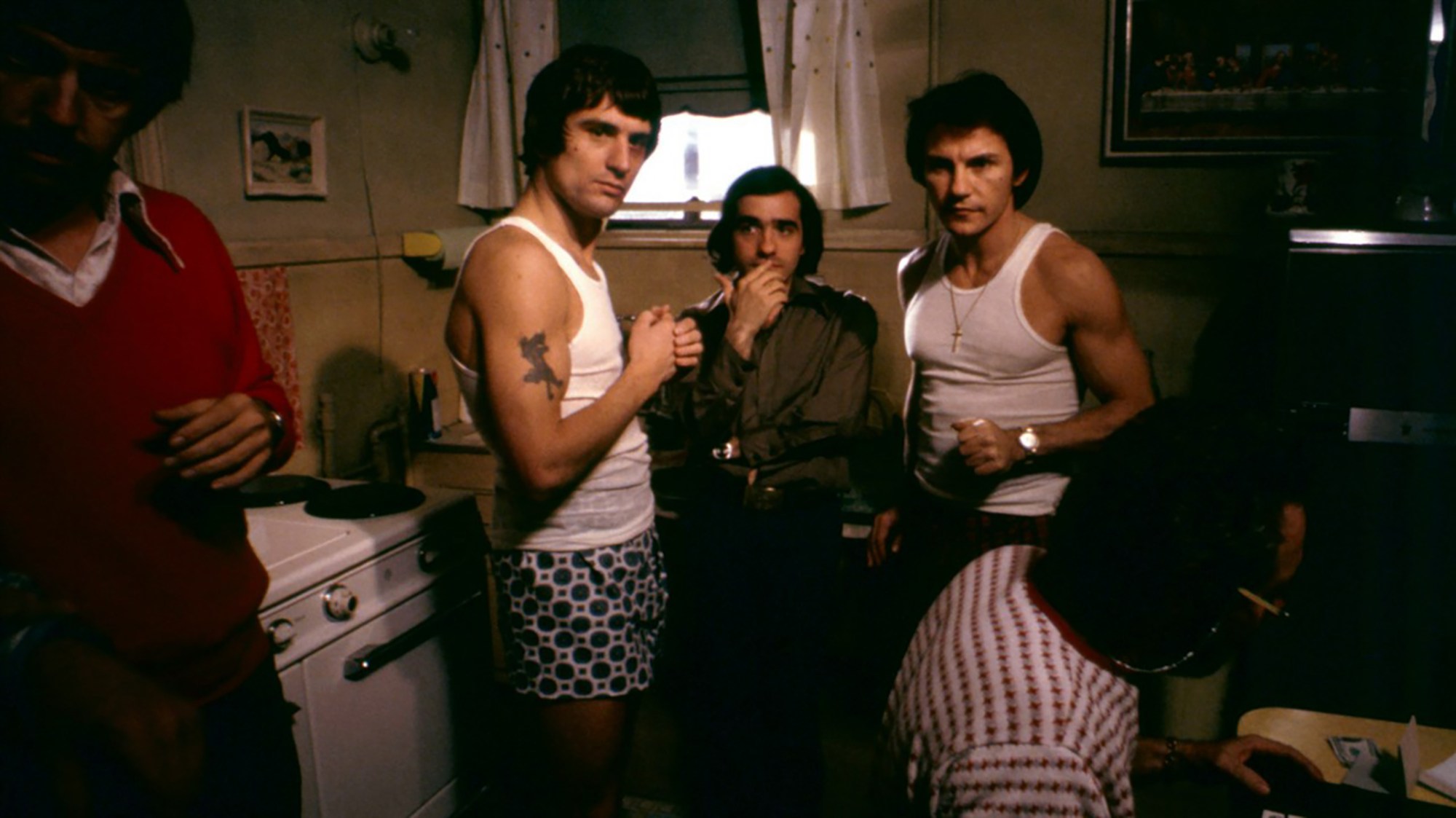

The entry point is… Mean Streets (1973)

For the film that first put Martin Scorsese on the map, Mean Streets is more of an impressive calling card than an all-round masterpiece. It feels like a dress rehearsal for what he would later achieve. That being said, Scorsese’s dress rehearsal is another director’s gold. It is the start of what would be a history-making relationship with Robert De Niro; a fantastically grimy early showcase for the actor’s sleazy, electric charm.

The plot is stripped down compared to later Scorsese movies, but it’s mostly a vehicle for him to develop a now deeply familiar visual language. Italian American mafiosi loiter in scuzzy Little Italy bars, illuminated by Argento-red lighting. Men are torn between their Catholic faith, their criminal dealings, their mistresses and their friends. It’s like a Scorsese bingo card and it all works. Mean Streets has a fluidity to it that Scorsese has never lost. In just one year, he went from making the runt of his litter Boxcar Bertha, a janky little Roger Corman B-movie, to what’s essentially a mission statement for the rest of his career. John Cassavetes allegedly called Boxcar Bertha “a piece of shit” and encouraged Scorsese to “try and do something different”. Scorsese followed his advice and never looked back.

The one everyone has seen is… Taxi Driver (1976)

Pop culture has bastardised Taxi Driver. It was Scorsese’s first titanic hit, taking home the Palme d’Or and earning him a slate of Oscar nominations, but its cultural footprint would have you believe it was simply responsible for a catchphrase, an easy Halloween costume and a poster typically seen on the walls of a uni dorm.

You may have read countless comparisons to the smug Joker, which cribbed heavily from it, but Scorsese lends a real nuance to its protagonist Travis Bickle. Here is an ineffably flawed man; a strange, scary, oddly endearing antihero. Our cultural understanding of fucked up male characters like Bickle has been backsliding for decades, compounded by the imprecise, lazy ‘toxic masculinity’ marker and, yes, the likes of Joker. You simply could not find a male character as rich and horrifying and meticulously performed as Travis Bickle in the 2020s.

Necessary viewing… The Age of Innocence (1993)

It remains extremely gauche to claim Scorsese is, in any way, a bloke’s director (many of us are still receiving therapy for the Anna-Paquin-has-few-lines-therefore-Martin-Scorsese-is-a-unrepentant-misogynist discourse around The Irishman). Critics who make such claims should watch The Age of Innocence.

It is heart-swelling; Scorsese’s most accomplished film. Adapted from the Edith Wharton novel and set during the Gilded Age, The Age of Innocence portrays the relationship between high society lawyer Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis in one of his finest performances) and his young debutante wife (an Oscar-nominated Winona Ryder) as Archer finds himself drawn towards the comely but – gasp! – scandalously divorced Countess Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer).

Like the best of Scorsese’s work it bunny-hops across decades and by the end it has run roughshod over your heart. Those three leads have rarely been better, and neither has Scorsese. The Age of Innocence is proof of his versatility as a director, as a proper romantic, to the point that it’s often outright forgotten as one of his films. For once, he suspended his 50 year love affair with Robert De Niro to concentrate on another great romance. The result is pure magic.

The deep cut is… Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

Shortly after she wowed in The Exorcist and long before she was dragged kicking and screaming onto the set of its legacy sequel, Ellen Burstyn scooped up an Oscar for her immaculate turn in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. The reason why Alice doesn’t live here anymore is because she’s a freshly widowed mother driving across America to start a new life with her young son. Like The Age of Innocence, it’s not what you’d expect from Scorsese, who is often defined by his New York-set crime thrillers, but again, this is a man who has always trafficked in different genres, approaching each with a similar care and curiosity.

Though it’s a smaller scale effort for him, mostly confined to kitchens and diners, it’s still got Scorsese’s cinematic flair. Alice crosses paths with different flavours of men, many of whom are abusive, and Scorsese’s intimate understanding of the corrosiveness of male violence lends these scenes a chilling and real air. Harvey Keitel’s performance in one key scene was so powerful it distressed Scorsese and Ellen to the point that the latter cried for an hour when the cameras stopped rolling. Ellen is characteristically exceptional as Alice — vulnerable, tough as nails, desperate, sharp. While Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore may be a niche Scorsese picture, it’s one that deserves to be spoken about in the same breath as Taxi Driver and The Wolf of Wall Street.

The slept on gem is… The King of Comedy (1982)

Whoever was responsible for the editorial content in the 1983 Entertainment Tonight New Year’s Eve special, your days are numbered. As documented in his latest TikTok appearance, Scorsese is still pissed about the criticism and box office failure of The King of Comedy back in the early 80s. Entertainment Tonight called it “the flop of the year”, gleefully seizing upon what they thought was a rare Scorsese miss. Oh, how wrong they were. Time has proven Scorsese correct because The King of Comedy is now regarded as almost supernaturally prescient.

It’s a film about how we view celebrities, as well as the parasocial relationships that mutate from consuming too much media. It’s about loneliness and desperation and how all publicity is ultimately good publicity. The King of Comedy is one of those films that feels too close to the bone; it foretold our current, ungovernable relationship with fame by about 30 years. The world is now overrun by people like Rupert Pupkin, De Niro’s lead character and a man so fixated on his own inadequacies that he projects it onto a talk-show host played by Jerry Lewis.

De Niro has rarely been more convincing, and considering the amount of morally compromised characters under his belt, Rupert is such a grim little sad sack that he ranks among the most disturbed. In 1983, The King of Comedy was another of Scorsese’s messed up fantasies, a black comedy not yet understood. But its increasing pertinence to our current reality has only sharpened its humour and darkness. Entertainment Tonight, are you not embarrassed?