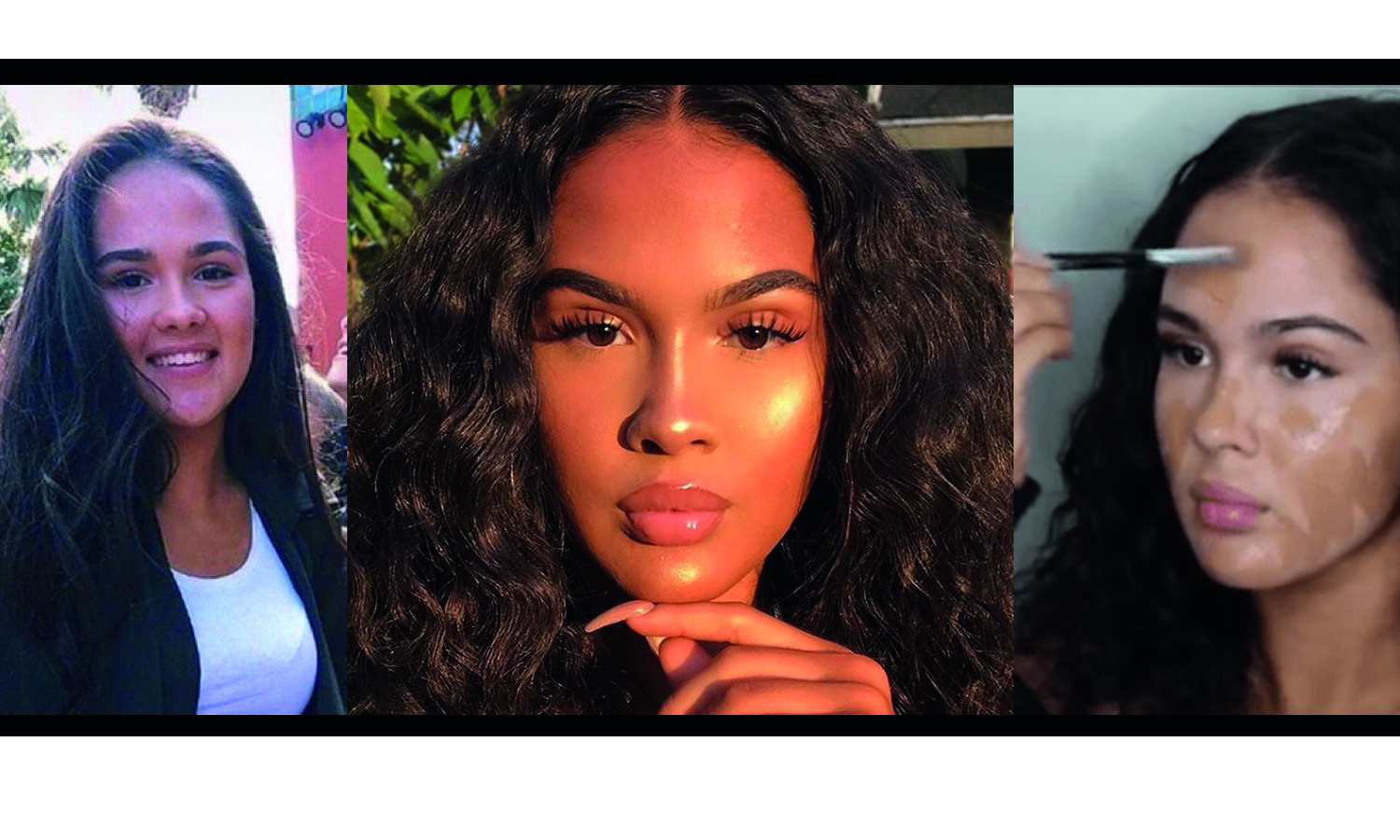

Last week a Twitter thread went viral for calling out white girls on Instagram and YouTube, some of them with huge followings, who are seemingly using various methods to transform their faces and bodies so they look “mixed-race” – though some have denied that’s what they’re doing, blaming their change on a propensity to deeply tan. Various media outlets are referring to this as “blackfishing”, but there is another name for it, which more clearly links this practice to its racist past. While “ni**erfishing” sounds like a sport from the good ole days when AMERICA WAS GREAT, when a picnic wasn’t a picnic without a black body swinging in the southern breeze, it is in fact a phenomenon all our own, from the year of our good lord 2018. N**erfishing is this cute lil trick whereby white girls literally reinvent themselves online, on Instagram and Youtube, as “mixed-race” or light-skinned black women. From our complexion to our lips and other facial features, to textured hair and the use of protective styles, weaves and braids — there is little to separate these white women visually from black women.

While it’s clearly a trend this year, the writing has been on the wall for a while now. From Ariana Grande to Rita Ora, white chicks’ profitability seems to soar if they can flirt with the suggestion of blackness, without being burdened by the reality of actually being black. Cultural appropriation has extended to body parts and many of today’s most celebrated beauties are white women with augmented bodies and faces who’ve been cut and carved to produce a facsimile of blackness; pumping their lips and arses full of god knows what, to achieve the same features myself and many others spent years of our lives being bullied for. You couldn’t make it up! Good thing you don’t have to.

There’s one family whose name I refuse to say, but it starts with K and ends with N. Some of the siblings have a different surname but they all seem to share the same surgeon, and certainly the same propensity to produce black children, which seems worthy of note given their desire to reproduce black features. These TV characters have made multi-billion fortunes off “their” looks, and mostly the make-up they sell by the shitload, usually to other white women who hope to recreate “the look”. Naysayers will be quick to point out that “it’s just a tan” or that “imitation is the highest form of flattery”. These people would be better served taking a quiet moment to reflect on the history that has created the hellscape in which these Instagram influencers flourish.

Some of these gals are convincing, I’ll give them that. These young white women from all over the world are really nailing their transformation from caucasian into seemingly “mixed-race” (in quotation marks because the concept is a social construct), through a combination of heavy make-up, hair styles, extreme tanning and, likely, some serious augmenting via apps. With their adjusted complexions, full lips and in some cases, rather rounded posteriors — they blow Rachel Dolezal’s black costume out of the water. That’s what these are, costumes — but blackness isn’t opt in and opt out. We can’t be black when it suits us, and then wash it off when confronted by the very real racism that continues to reduce our realities.

But it’s also crucial to remember that to be black is about more than just skin colour, hair texture or experiences of racism, it is also to be heir to a rich cultural legacy that western culture seems particularly enamoured by, which is somewhat perverse when you consider attitudes to black people. Yet so much of what we understand as western culture would be non-existent without that gift that keeps giving; unacknowledged physical, cultural or material black labour. For centuries, women of African descent have been conditioned to believe that their looks are inadequate and inferior to white women’s. I grew up feeling like I was unspeakably ugly. I thought my bum and thighs were fat and monstrous, I was deeply ashamed of my hair. I had constant jibes about lips, and my skin complexion, while very light by black standards, was not spared being frequently likened to dirt. I’ve been called a black bitch and a nigger more times than I can count.

In addition to all of this good stuff were the assumptions about my sexual availability and perceived licentiousness as a black woman. This didn’t only come from men. The recent accusations by Zoe Kravitz about being sexually “attacked” by Lily Allen, really hit home. She reminded me of my numerous encounters where drunk white women have groped me and/or attempted to stick their tongues into my mouth. I remember one incident where a particularly eager assailant physically tried to force open the door of the cubicle I had locked myself into to escape her advances, while she told me she “knew I wanted it” too.

Yet in constructions of beauty, black women’s physicality was used to provide the rationale for white women’s beauty. As Professor Patricia Hill Collins wrote: “Within the binary thinking that underpins intersecting oppressions, blue-eyed, blonde, thin white women could not be considered beautiful without the Other — black women with African features of dark skin, broad noses, full lips and kinky hair.”

However, in the years since that was written (in 2000), the “skinny white blonde” standard has been somewhat displaced from pole position — a new beauty standard is emerging and its manifestations are troubling. At this stage in my life I’ve mostly overcome the belief I once had that I was ugly and inadequate. I can recognise the features I was bullied for are — quite simply — beautiful. It’s not just me, collectively black women are decolonising. We have beautiful features, and we know it! The infrastructure designed to convince us that we were worthless and inferior is crumbling, and now that so many of us are boldly embracing ourselves, a shift is happening. Black girl magic is real and these white girls want in. That’s where the “mixed” body comes in. The African ancestry presumably provides the hypersexual swag, but mediated through European ancestry, so that the features are likely to align more closely to Eurocentric beauty standards.

Advances in beauty products mean now they can look just like us. I suspect many always wanted to, certainly the antecedents have long been there. While so much effort was invested in pushing this narrative that black women were ugly and inferior to white, there was a long history of jealousy directed from white women towards black. Evidence of this jealousy was enshrined in law, for example in 1786 when Esteban Rodríguez Miró, the governor of the then Spanish colony of Louisiana enacted the Tignon Laws, which decreed women of African descent must cover their hair in a tignon, a headscarf, effectively forbidding them from revealing their hair. White women felt that the intricate and often ostentatious styles black women could achieve positioned them at an unfair advantage in attracting the attentions of white male suitors. The law was enforced, but to little effect, as black women wore their tignons wrapped in beautifully elaborate styles and remained much admired by the male population. This wasn’t the only time the politics around hair revealed a jealousy at the heart of oppressive relations between black and white. Light-skinned black women have existed in the diaspora for as long as there have been black communities in the New World. In America, for example, at least 3/4s of the black population are in fact “multiracial” (they are still black, because, remember, race is a social construct, right?).

The existence of “mixed-race” enslaved people was direct evidence to white women that white husbands, sons and male relatives were sleeping with black women. “Mixed-race” slaves were a visual reminder of this deception, and their features could prove a flash point. There are many accounts of enslaved women, particularly those with a texture thought to be too close to European, having their heads shaved, a punishment frequently meted out by white women. The wives of plantation owners were often quick to suspect that these women had duties that existed far beyond the domestic ones they were ostensibly kept in the house for. One particularly distressing account I came across was a case where a “mulatto” slave had her eyes cut out by a jealous wife, who believed her husband had taken a sexual interest in the girl. These are not stories from some dark distant past. They are events from the 19th century.

By the 20th century these stories had morphed into stereotypes about “mixed-race” black women, which migrated into popular culture, where we now had the privilege of being represented as “tragic mulattos”; according to white supremacist discourse, the mulatto did not have the “right to live” the US senator Charles Carroll said in 1900. We were an abomination who disrupted the racial order, and as a result of our pathology were emotionally unstable, yet we were still perceived as seductresses. And that’s why it’s no coincidence that when these online imposters post as their light-skin black alter egos they post thirst-traps with sultry eyes and pouty mouths, yet in photographs as their white selves, they remain smilingly wholesome girls next door. They are operating in familiar terrain, reinforcing topes that emerged out of slavery and which have been developed and refined via mass media throughout the 20th and 21st century. None of this is about flattery, it’s about power, desire and ownership. A sinister reminder that people who once owned our bodies, still can, and of the troubled history and deep seated taboos that continue to define race relations between black and white in the 21st century.

Editor’s note: This piece has been updated to reflect a particular Twitter thread as the one that went viral on this topic.