This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Ultra! Issue, no. 369, Fall 2022. Order your copy here.

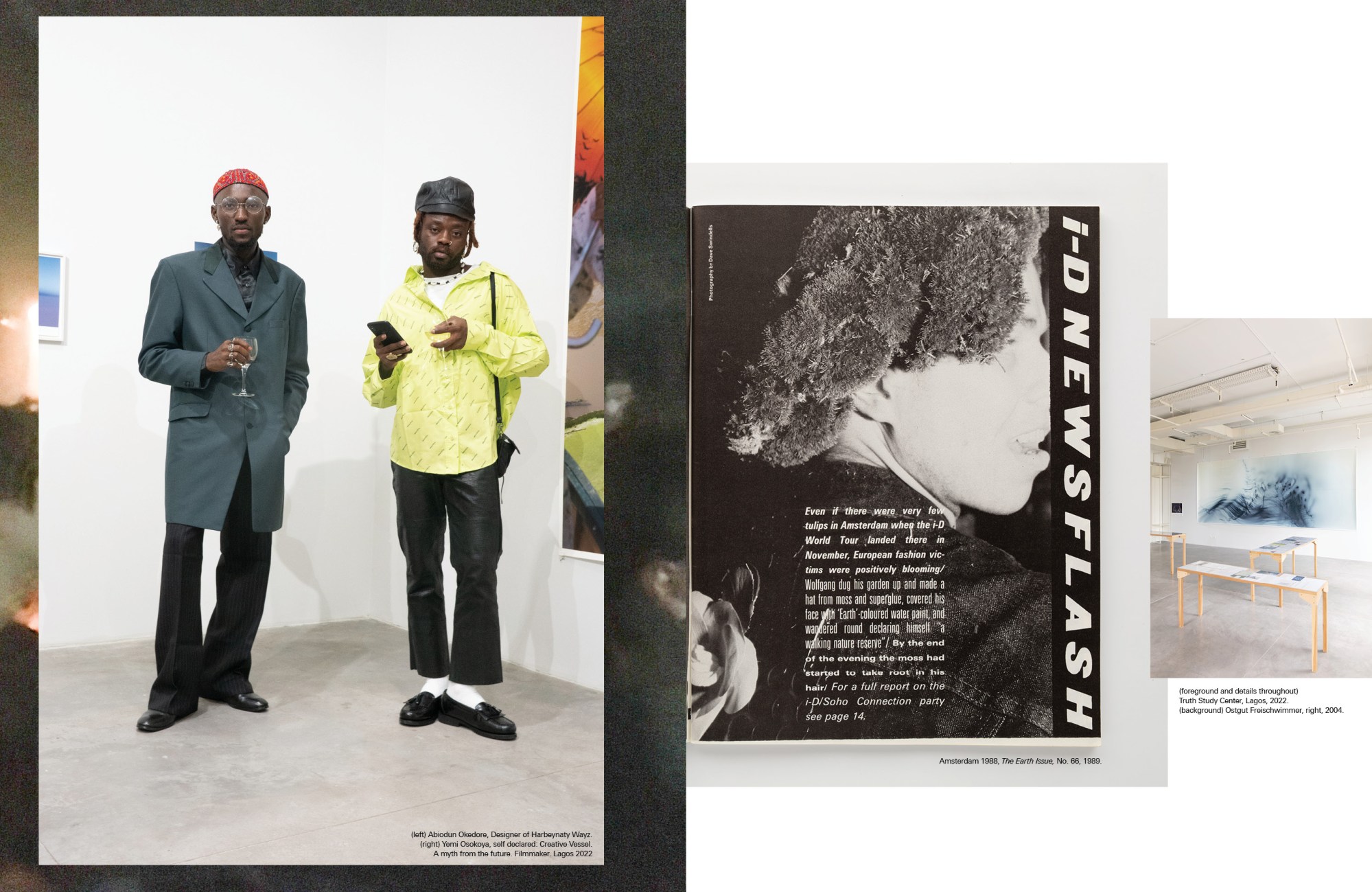

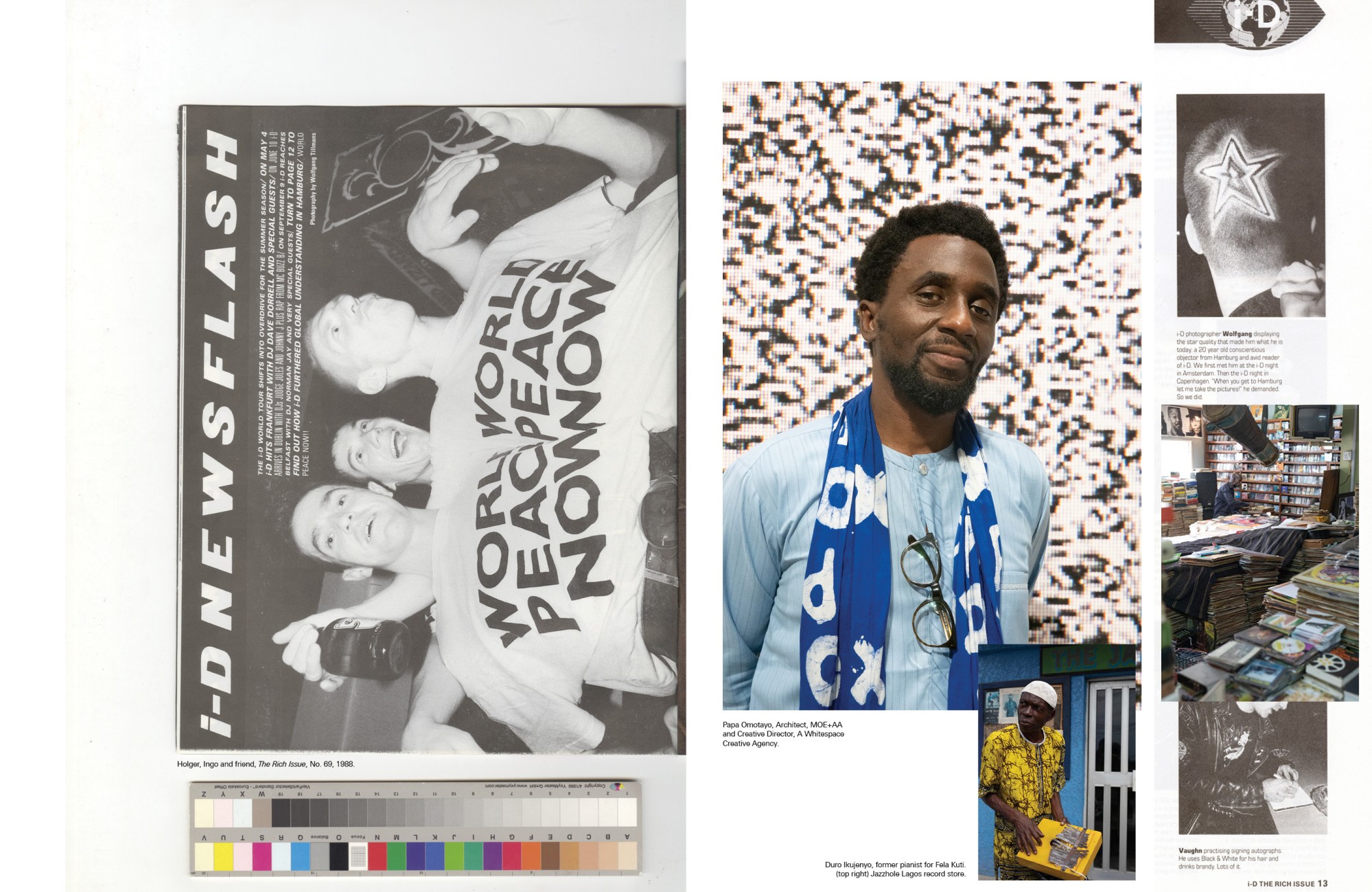

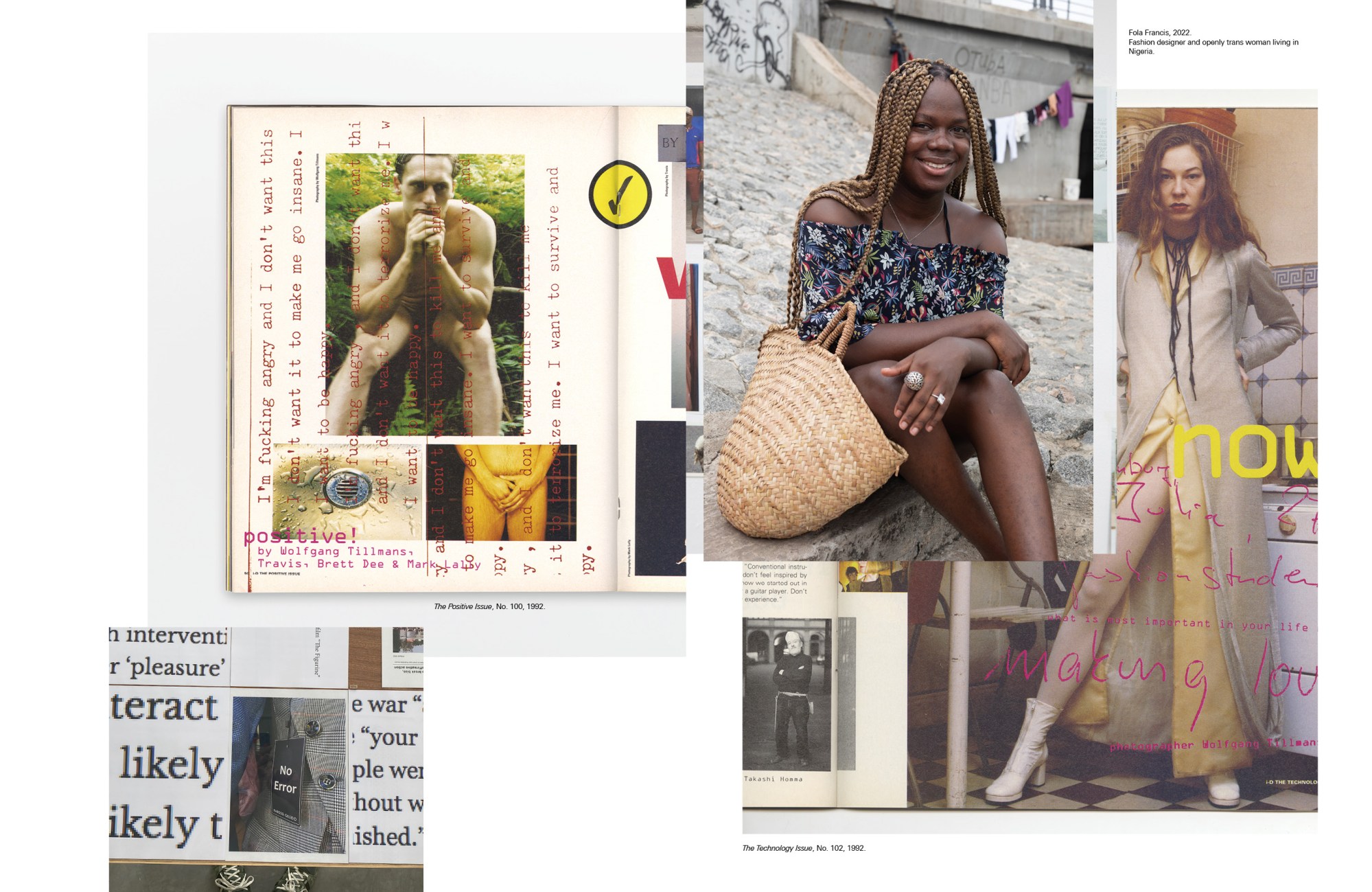

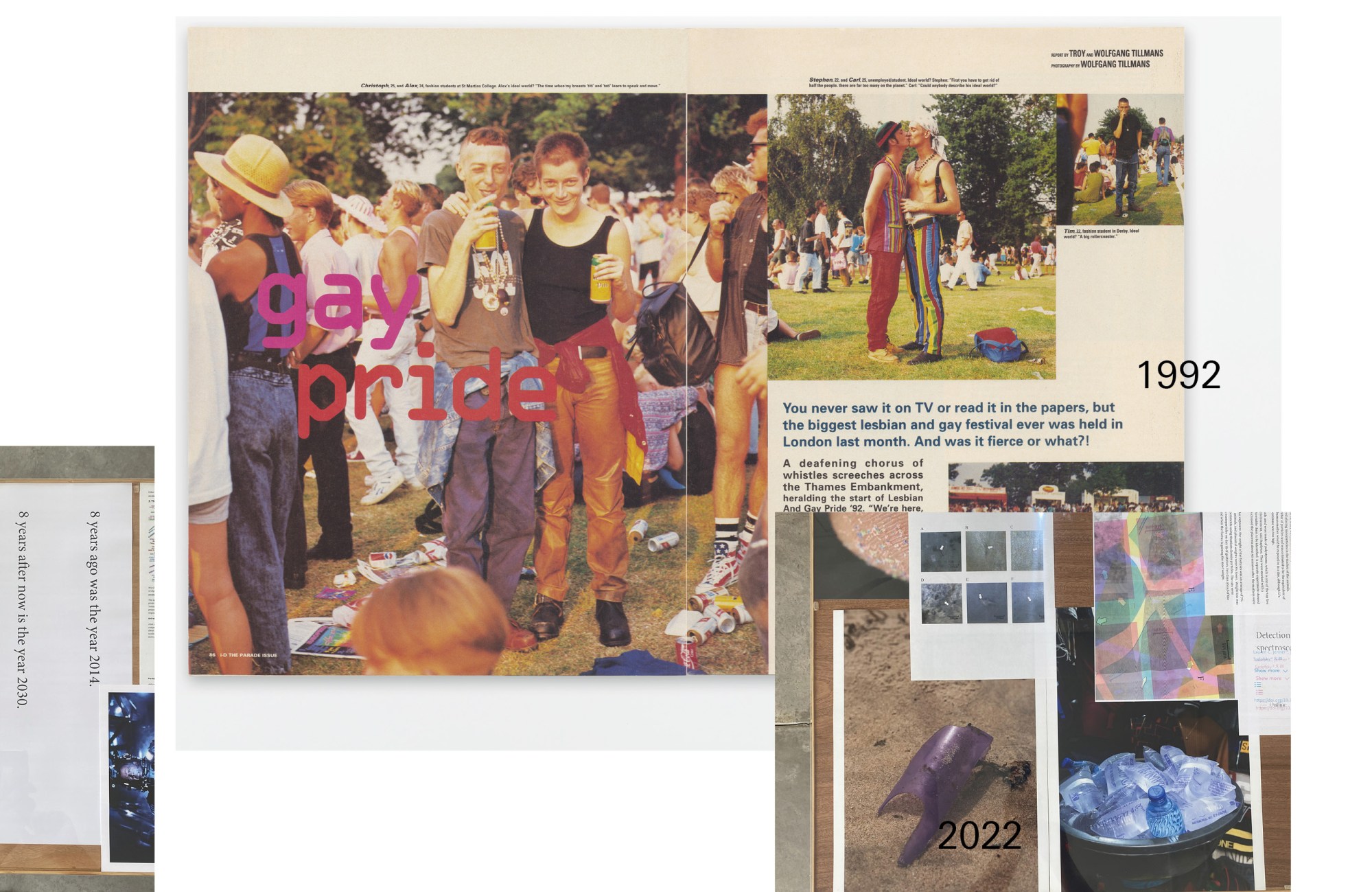

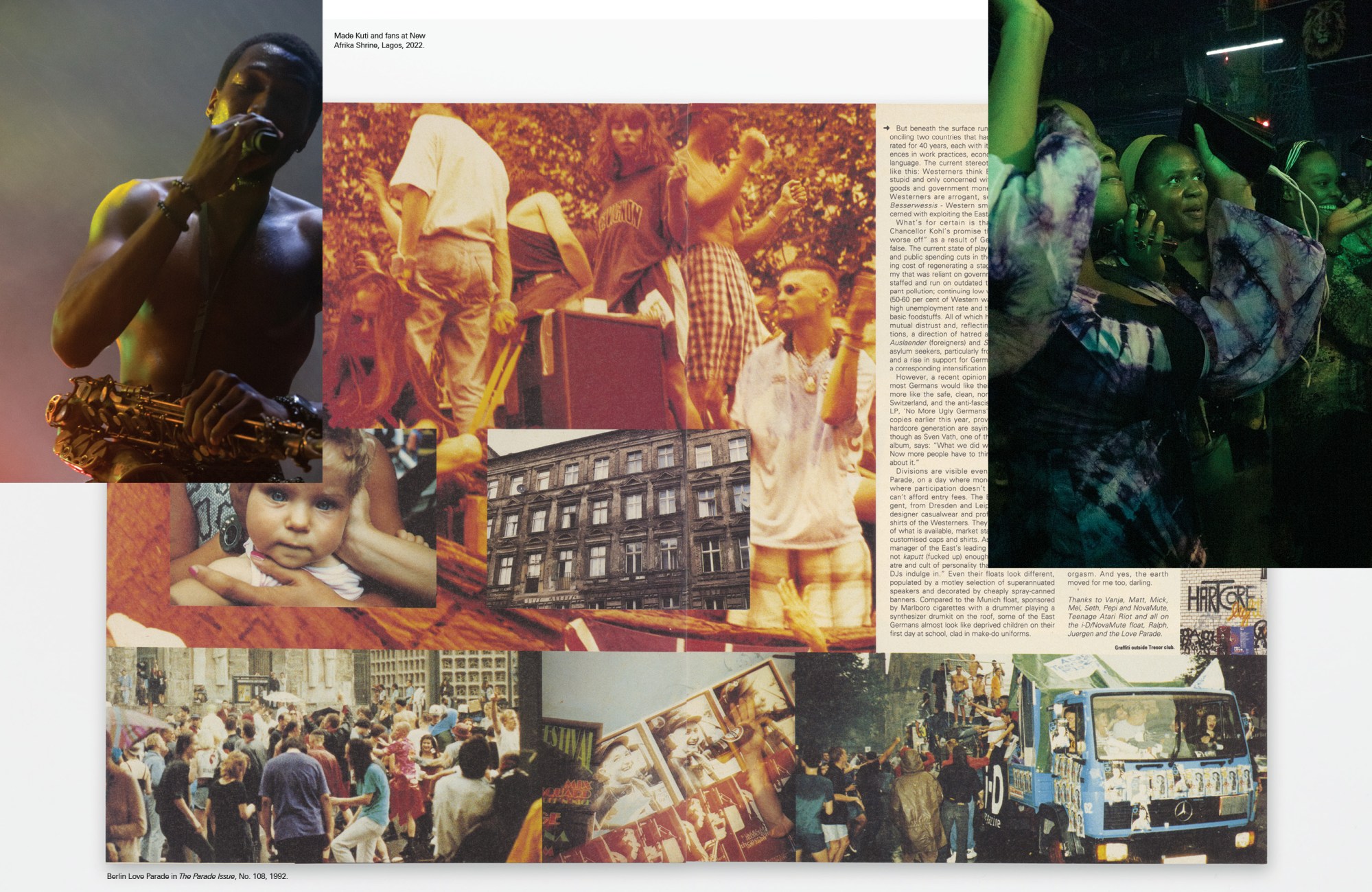

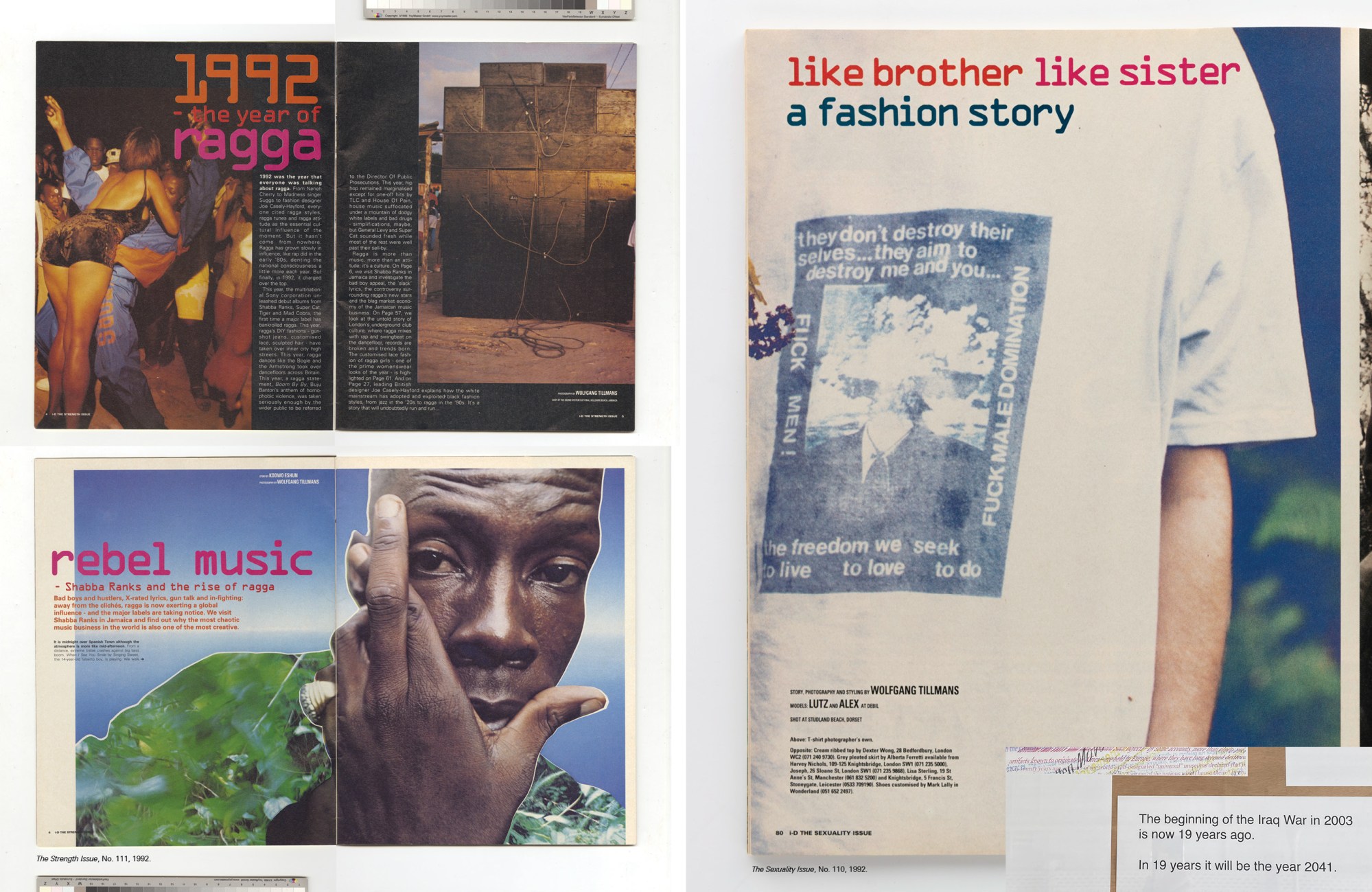

On the eve of his large scale survey exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Wolfgang Tillmans – an i-D contributor since 1989 – made this collage of i-D pages from the early 90s (which he often designed himself) and photographs he took this year in Lagos around the opening of his exhibition Fragile at the two art spaces CCA and Art21.

Her/His/Theystory is now.

The title of Wolfgang Tillmans’s retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art is To Look Without Fear: a plea for visual consciousness in a battered and vulnerable world. For more than three decades, Wolfgang has modelled a kind of open, extroverted view of things, photographing all aspects of his life and world. His exhibits overflow with impressions. There are dreamy encounters with nature, portraits of friends, allusions to loss and devastation – images of his late partner, the painter Jochen Klein, who died of complications from AIDS in 1997. His work also refers to blatant injustices. A photo from 2000, Anti-Homeless Device, shows an un-housed person asleep on the sidewalk next to a block of ribbed cement.

Always, there is attention to atmosphere and composition. He’s clearly fascinated by the way afternoon light transforms a piece of trash into a glittering still life. Or, when the light is dull and incandescent, how it mutes feeling or blunts erotic attraction. When Wolfgang shows his work, the pictures are arranged in loose clusters; you wander between them, stopping to look as the room expands and contracts around you. He has described the “ebb and flow” of his displays, the “different densities” he uses to make you feel a part of a swelling visual tide.

The sense of inundation is, of course, deliberate. Wolfgang is showing how visual media trains our ability to look and to see for ourselves. As he said in 1995, “there is an encyclopaedia of representation that is in our heads almost since the day we were born.” He speaks of his own childhood: he had “a fascination with print from an early age,” looking at his father’s Time magazine and copies of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Most striking was the way the newspaper transmitted political events – “photographs of terrorist attacks in the late 70s burned themselves into my retina,” he has said – also the physicality of the artefact, the smell of newsprint and the weight of paper in his hands.

His career is itself a study in media distribution. The first works he exhibited were Xeroxes of Xeroxes, shown at a cafe in Hamburg, followed by photos of parties shot on a point-and-shoot camera. Later, after publishing a huge volume of work in magazines like i-D (more on that in a minute), he switched to a digital camera and large format digital printer. Now, like virtually all photographers, he is on Instagram, posting every kind of image and video, as well as flyers, agit-prop, personal statements, and newspaper articles. His work mimics and critiques the media ecosystem in which we live, and which enables new, sometimes unhappy forms of social experience. The swirl of image in the gallery is continuous with the interface of the cell phone in your pocket – the source, supposedly, of limitless mobility and interaction, but also a cause of anxiety for young people everywhere.

You could say that Wolfgang shares these mixed emotions and also that he exacerbates them. The obvious pleasure of his photos, their libidinal power, their movement and evanescence, is combined with a sense of split attention and lost bearings, as if the world were coming apart. At times his pictures are tender and lyrical – they are islands of calm in a sea of visual chaos – while at other times, they express frustration.

The flux of the world can be confusing, even misleading. Lies and fabrications are, after all, what led liberal society into the spiral of wars (like the US-led invasion of Iraq) and, later, into the elections of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, and the rise of the AfD in Germany. Much of Wolfgang’s most recent work is devoted to examining these disasters and the role of media in provoking them. His Truth Study Center, begun in 2005, was the first part of this inquiry. On plywood tables, he lays out photographs and news clippings alongside propaganda and misinformation (in 2005, the term “fake news” hadn’t yet been coined). Even though the project alludes to government predations and the fealty of corporate media, it is characteristically brainy and, in its own way, optimistic. He delights in the idea of a public at work, deciphering these materials, making judgments (he told me he “always loved the look and the sound of science and research”). But it’s clearly a rehearsal for the challenges that are, in today’s media context, all too obvious.

What he is trying to communicate is the play of appearance in our lives: the bounty of visions that sustains us, yet also gets in the way. The whole field of visual media becomes, in this interpretation, a space for reconstruction and critical resistance, hence his collaborations with LGBTQ activists in Russia and in Kenya’s Kakuma Refugee Camp. Or the work of his Between Bridges Foundation, now located in Berlin – a hub for conversations on the crises of racism and inequality. He recently presented his work in Lagos (the exhibit, Fragile, closed in July), where homosexuality is illegal.

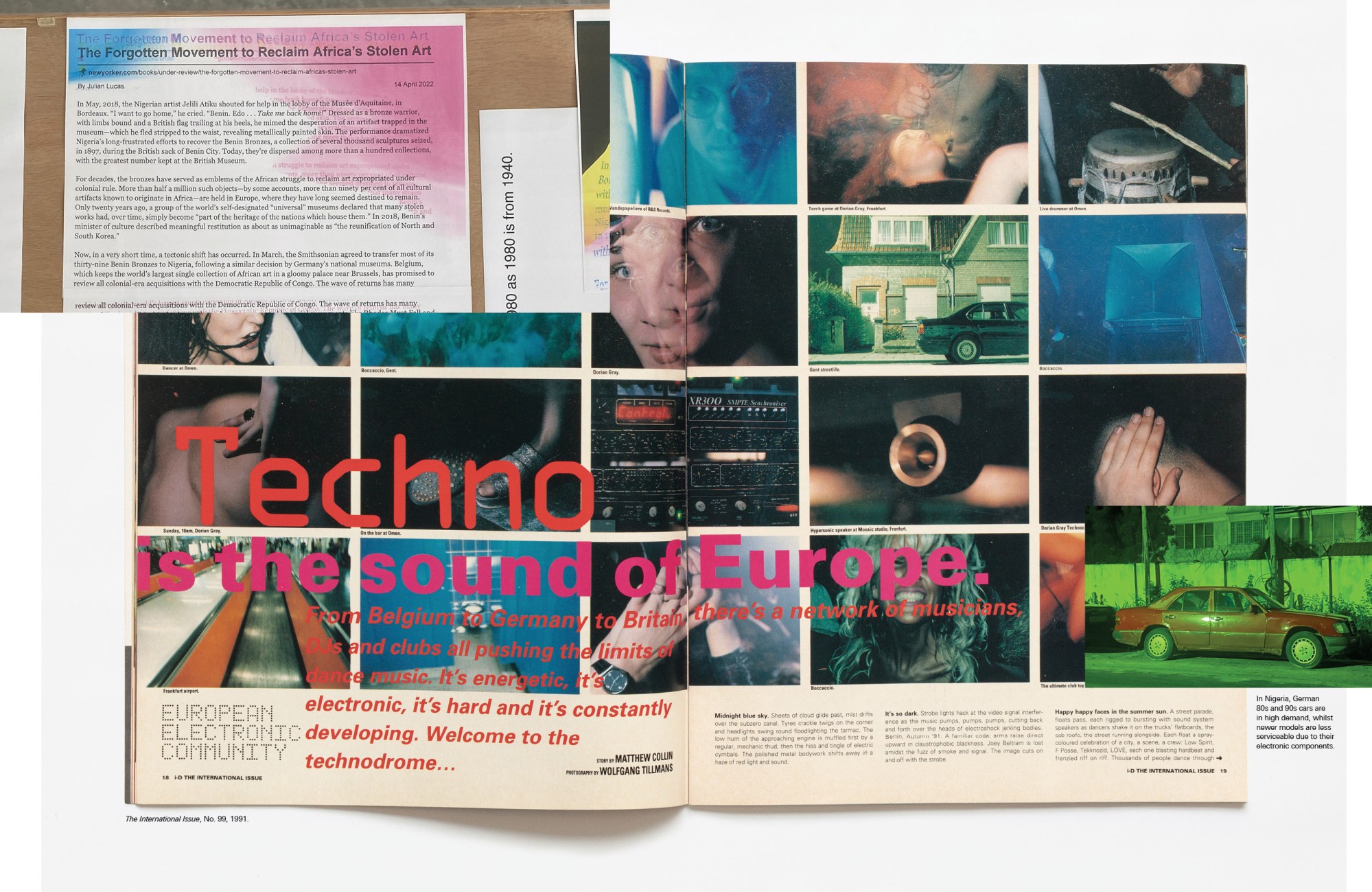

These are overt political interventions. But Wolfgang has also modelled the kind of roving, itinerant practice that ventures outside representation, beyond talk of awareness. He believes in the power of musicians, artists, and designers to generate kinship and affinity, defying political conventions by gathering community anywhere. In the early 1990s, in a spread for i-D titled Techno is the Sound of Europe he documented his travels across the continent in the company of ravers and electronic musicians. A grid of photos shows ecstatic faces, hair stuck to sweaty foreheads, switchboards and amplifiers, train stations, aeroplane engines, and (with winking humour) the entrance to a public bathroom. There are clear resonances in his portraits of activists at gay pride festivities and his photos of peace marches. In 1992, he visited the Love Parade, a huge dance party and demonstration in the streets of a newly unified Berlin. That same year, with writer Kodwo Eshun, he created a spread on the rise of ragga in Jamaica and beyond. The pictures are an assertion of pleasure and popular power. They make an argument: “That’s how living together could be,” Tillmans has said, “being peaceful and enjoying the senses.”

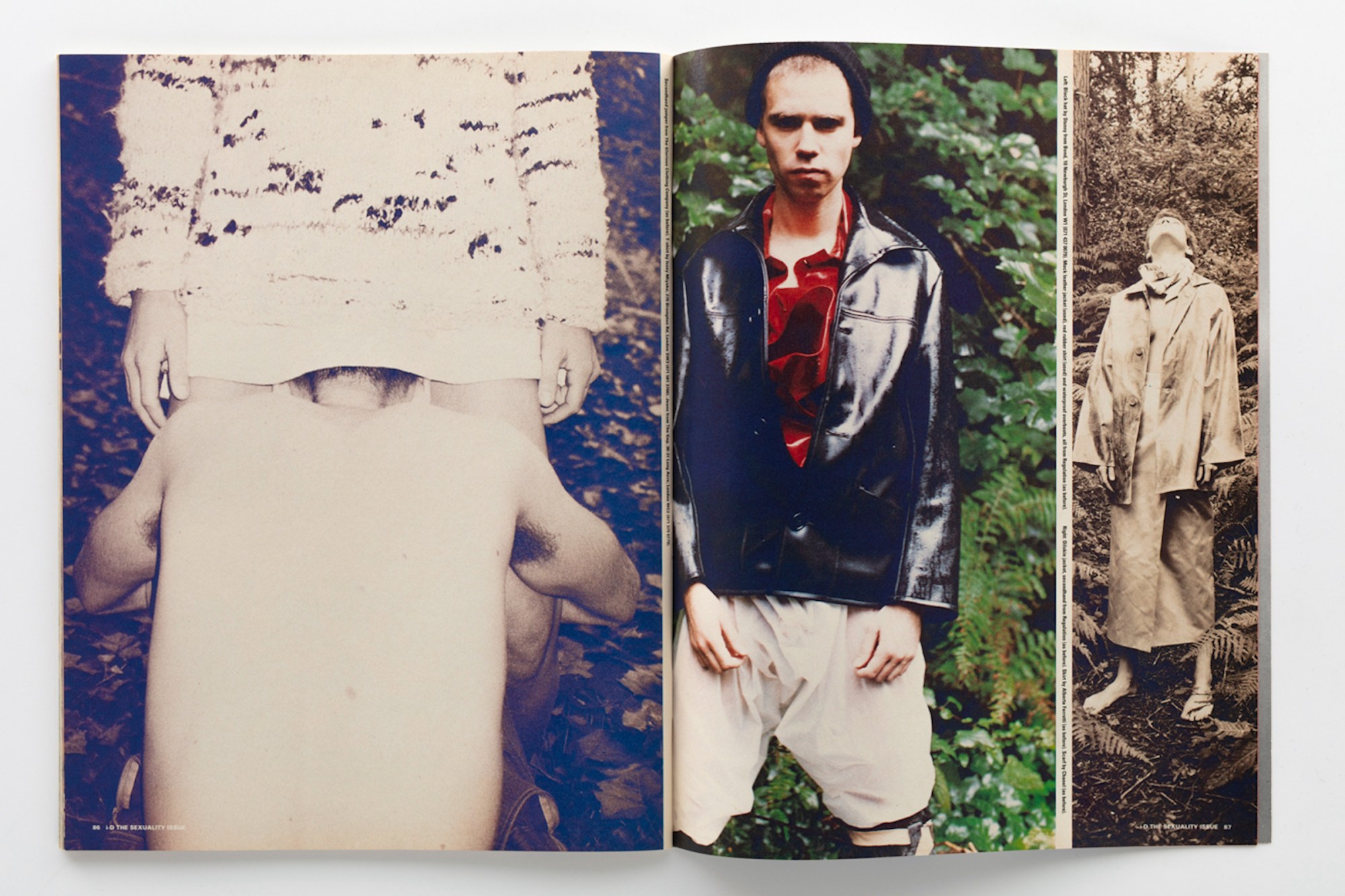

Telling this story is important – it shows another side to political media and to politics in general. The forces of bodies in motion, hands in the air, draw people into a common space of contact and relation, where they interact with a whole web of creative practices. Zines, patches, posters, party photos, ironic fashions like camouflage and safety pins – these give dimension to a deeply aesthetic, yet always political world. Tillmans describes the profound sense of freedom he experienced in the early 90s (making £40 per page working for i-D) not just because he could lay out his own work, developing a personal aesthetic sensibility, but because he could photograph what was important to him. He was free to realize his agency as an artist – a queer artist – to experiment and to participate, to become a political subject alive in the world.

There is a war on queer people, transgender people, women and minorities. It continues to this day. The space of politics cannot, under these circumstances, be confined to corporate media, to what passes for the public sphere, or to the halls of government. Private life must also, in a sense, become political. The photographer Nan Goldin recently said photo books – like magazines, postcards, even polaroid photos – may be the best way to experience photography, for they offer a withdrawal into intimate spaces of friendship and conviviality, merging with the flow of life that’s already there. For queer people, especially, a disordered apartment, or a bedroom with the door closed, can be a very special world – sometimes the only place where you can really be yourself, or make the community you need to survive. A photo book is like a samizdat that defies the rules of public and private. It is a promise: you are not alone.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.

Credits

Photography Wolfgang Tillmans, from the i-D archive