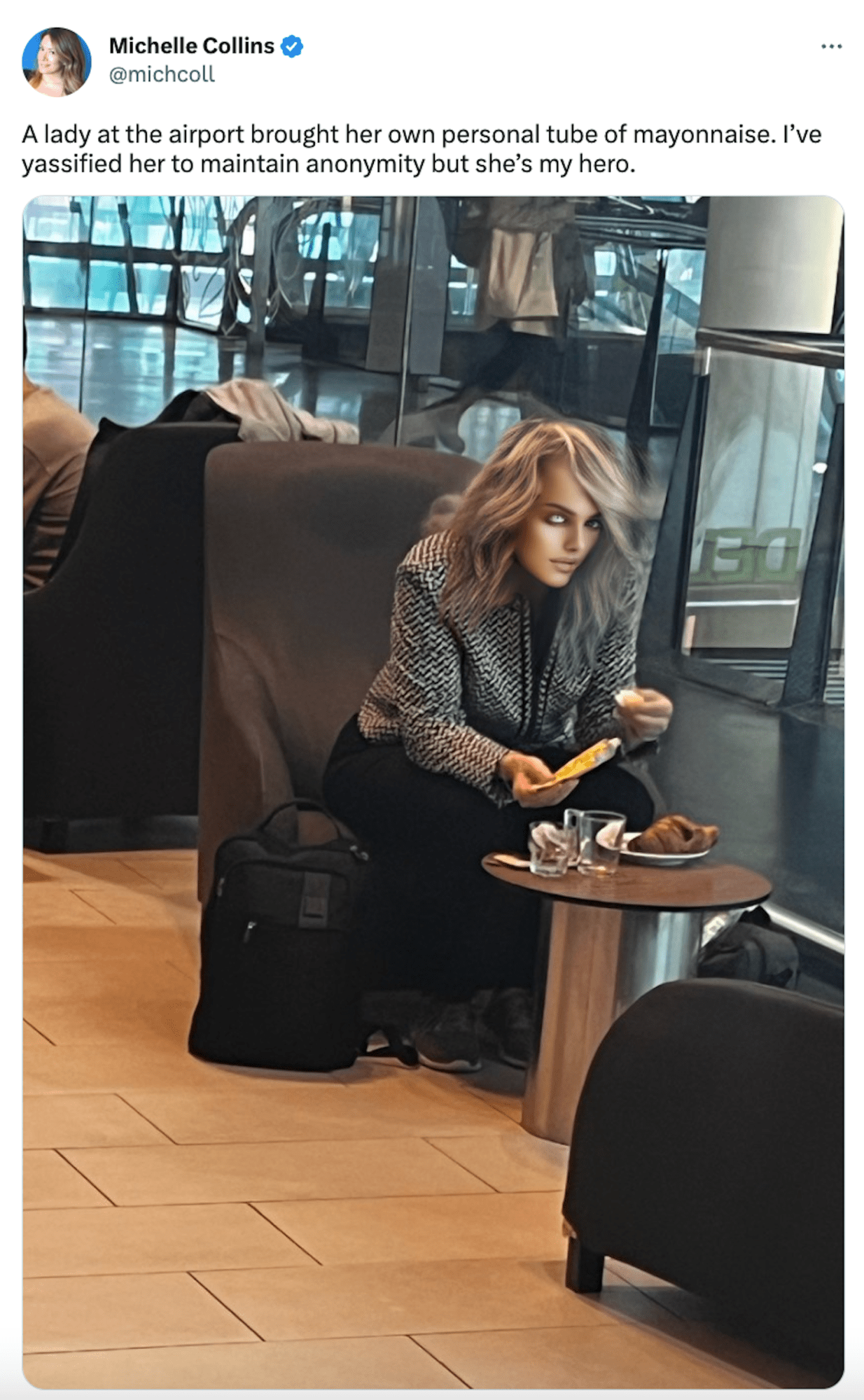

When Michelle Collins, an Amsterdam-based comedian and self-described “mogul”, spent $110 to upgrade to business class on KLM Royal Dutch Airlines last month, she found herself “face to face with a hero”. “A lady had brought her own tube of mayonnaise to lube up the hard-boiled eggs the lounge had in welcome bowls,” she says. Michelle didn’t feel comfortable posting the woman’s face online while she “innocently chugged eggs”, but wanted to share the moment with her Twitter fans. “I ran her through the FaceApp mill, giving her every feature plus side bangs,” she says. “If you’re going to post someone without their permission, don’t they at least deserve a makeover from the depths of hell?”

Michelle’s original Tweet states that she “yassified her to maintain anonymity”, a phrase that has since gone viral (after yassification memes took over our feeds in 2021). While clearly absurd, the hilarious phrase perhaps offers a solution to one of the pressing issues of our time — digital privacy in the age of surveillance capitalism. In the UK, there is roughly 1 CCTV camera for every 11 people (meaning you’re likely to be captured up to 70 times a day). On top of this, the abundance of smartphones means we’re all constantly a click of a button away from becoming a viral stranger video on the internet. Whether it’s a “random act of kindness” video filmed without consent or someone Tweeting about you eating “a whole Viennetta, with a metal spoon” on the London-Paddington train, we’re all being watched and recorded (and thus, slightly strange eating habits are being exposed).

Albert Fox Cahn, Executive Director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, says taking a video of a stranger in public is called “distributed surveillance”. It can be most harmful, he says, when being done at a protest. “Those who are taking photographs at protests against police violence are giving the police yet another way to track protesters, putting the activists around them at risk,” he says. Because of this, he says we shouldn’t be making people “props” in our social media feed without their consent. “A lot of the time, the consequences might be trivial, but in high-risk settings [such as protests and reproductive health facilities] the stakes can be huge.”

As someone who’s dedicated his life to digital privacy, Albert has (naturally) seen the viral yassification Tweet. Unfortunately, he says that using a filter may not be enough for “true privacy protections”. “Showing someone’s location, belongings and outfit often is still enough to reveal their identity, even with their face updated,” he says. This, of course, is less serious for the cases of egg eating and viennetta-spooning, but is important to keep in mind for the more high-risk scenarios.

Joselyn McDonald, a design educator and program designer at NuVuX, has previously explored using flowers as a means to undermine facial recognition technologies in her Mother Protect Me project. While she thinks that posting strangers online with their consent is fundamentally rude, she also thinks that yassifying them before you do it is “probably the most hilarious way to do it and better than not doing something to somewhat anonymize them… I thought it was pretty brilliant because typically when we think about resisting surveillance, tactics tend to go towards camouflaging, but in my work and in the yassified tweet, there’s a push towards using beauty and play as alternative paths to undermining surveillance,” she says.

Using beauty as a tool against surveillance is also nothing new. The group Dazzle Club has been using anti-facial recognition face paint to bring awareness to privacy issues for years. Georgina Rowlands, member and co-founder of the Dazzle Club, says that she’s noticed a “growing awareness of online consent” recently. “When my peers snap a photo of a busy tube train or central London street, they often scribble marks on the face using the drawing tool or use several emojis,” she says. “This is especially common when children are featured in photos.”

Georgina says that yassifying strangers is not only a tactic for protecting people’s identities, but also serves as a larger critique of online culture. “Not only is it effective for anonymising a person, but it also pokes fun at influencer culture and comments on how using beauty filters actually work to render a person completely unrecognizable rather than more beautiful,” she says. Despite this, Georgina says that there are concerns about FaceApp storing data and potentially selling it to AI developers to train algorithms, or even to the police for adding to their facial databases (something the app has denied). “It might not be fully ethical to sacrifice a stranger’s facial data in the kind act of anonymizing them so perhaps an emoji placed over the face, despite being less funny, might be more ethical,” she says.

SUBSCRIBE TO I-D NEWSFLASH. A WEEKLY NEWSLETTER DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX ON FRIDAYS.

When it comes to protecting the digital privacy of those around us, sometimes the biggest yassification of all comes from within (choosing just to enjoy the magic of egg lubing IRL). However, if you do feel the urge for some online validation, yassifying a stranger will always be better than posting their face raw to the entire online world. Even better, a cute face-crop or peach emoji will ensure you’re on the right side of history when it comes to the raging online privacy war — and remember that posting anyone at all (yassified or not) at a protest or medical clinic is unethical weirdo behavior.

After all, just because the police are keeping track of our social media with very little oversight, doesn’t mean we need to give them more material to work with. And just because the government is watching us all almost 24/7, doesn’t mean we have to embarrass a stranger for enjoying a delicious meal on the train or a few hard-boiled eggs in the business class lounge.