This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Ultra! Issue, no. 369, Fall 2022. Order your copy here.

Fifty years ago, in 1972, a revolution stirred as Yohji Yamamoto began making menswear-inspired clothes for women in his hometown of Tokyo. Having spent a couple of years wandering around Europe, where he was awarded a scholarship to study couture dressmaking in Paris, he began to unpick every seam he had been taught to hand-stitch. Channelling the beauty of darkness and poetic destitution, he created enveloping silhouettes in purposefully aged fabrics in only the deepest, darkest shades of black, worn with pallid bare faces, flat shoes, and jauntily uneven hems and finishings.

A young Yamamoto-san had visited Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McClaren’s epicentre of punk, Sex, a couple of years prior in London with his then-girlfriend Rei Kawakubo. It sparked a desire to destroy everything he was ever taught in order to sow the seeds for something new. “You will only be able to oppose something and to find something of your own after travelling the long road of tradition,” he explained in his own words.

In 1981, he arrived in Paris, where his debut show under his own name created a fork in the path of fashion’s future; Kawakubo showed her first Comme des Garçons collection in the city that same season. In his small store on Rue du Cygne, the designer staged his first show to a handful of guests, making a case for clothes that celebrated the spirituality of imperfection, the beauty of transience, and black: a colour worn by the religious orders in the Middle Ages, by the scholars and thinkers of the humanist Reformation, by the Dutch burghers and Puritan divines of the 17th century, and by the austere Spanish nobility. But perhaps most importantly, by Yohji’s mother, Fumi Yamamoto, who lost her husband, Yohji’s father, in the Second World War, and worked sixteen-hour days as a dressmaker to put her son through school.

“For me, a woman who is absorbed in her work, who does not care about gaining one’s favour, who is strong yet subtle at the same time, is essentially more seductive,” Yohji has said. “The more she hides and abandons her femininity, the more it emerges from the very heart of her existence.”

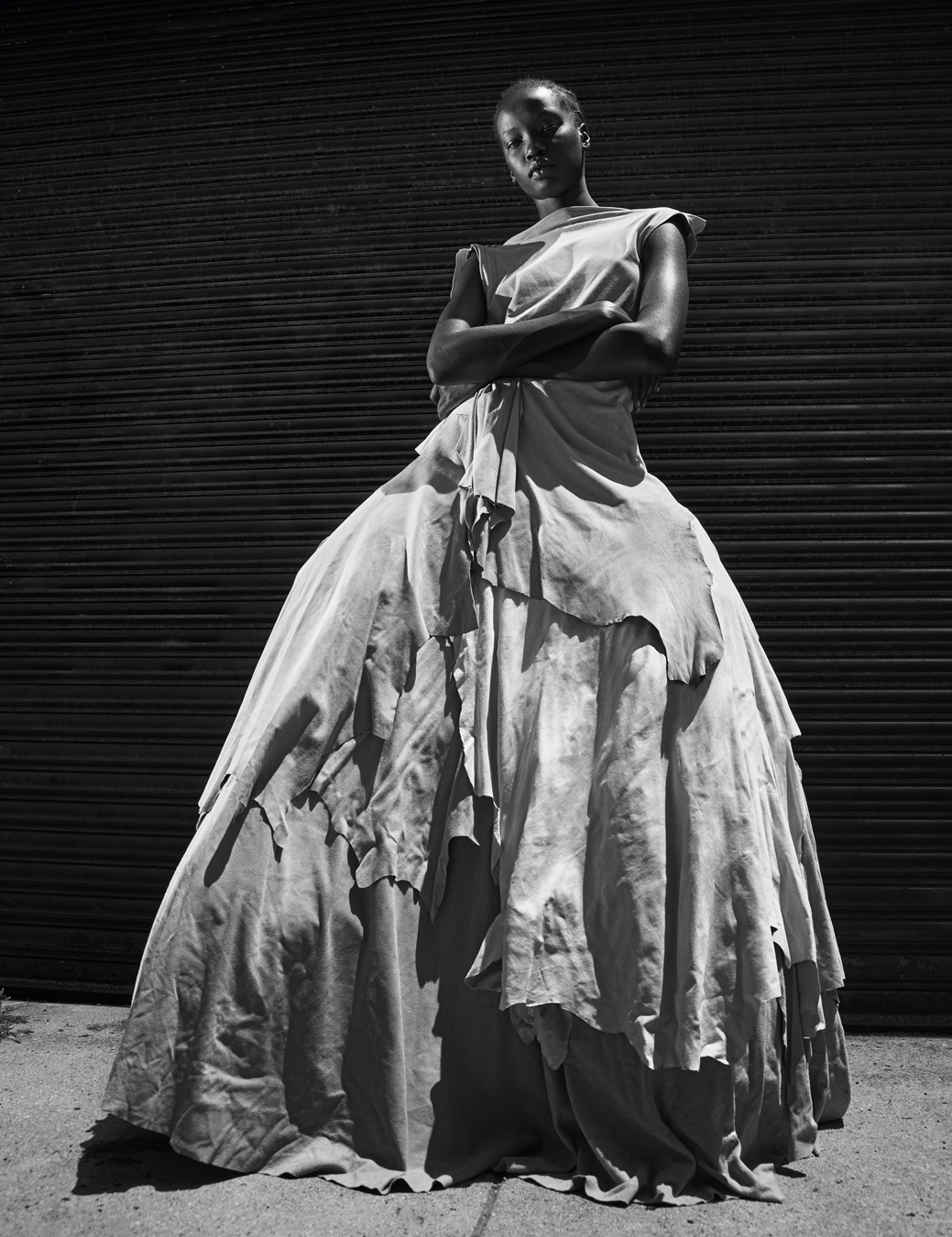

These were clothes that wouldn’t look out of place in the photography of August Sander, or among the post-war ruins of cities; clothes that came with a slogan printed on the labels: “There is nothing so boring as a neat and tidy look.” Humble and purposefully imperfect, they offered a hypnotic shadow to the candy-coloured visions of hourglass femininity that prevailed at the time. Whereas his contemporaries Claude Montana and Thierry Mugler’s jolie madame clothes were expensive and resplendent – a spectacular parody of femininity fuelled by consumption – Yohji (and Rei’s) post-punk rags defied convention just as they defied the classical shape of the human body and centuries of clothes tailored to sharpen its silhouette.

Their boiled wools, cut-outs, ragged edges, tears and knots paved the way for a dramatically despondent vision of womanliness; a vision of ‘grunge’ long before it leapt from Seattle to MTV and the catwalk of Perry Ellis. “In the beginning, I wanted to be very tough, to challenge people’s ideas of beauty and to fight conservative values and the establishment,” Yohji has said. “I was very tense, always battling.”

Much has been theorised about Yohji’s designs in relation to traditional Japanese aesthetics: whether that is the shift in samurai’s hakama robes in the late 17th century, or lavish custom-made ceremonial kimonos to more sober everyday clothing, the sense of spareness and negative space in haiku poems, nihonga watercolour paintings and ikebana floral arrangements.

In Yohji’s own words, “perfection is the devil”. But the restraint, subtlety, incomplete perfection and austerity of Yohji Yamamoto was xenophobically exoticised. At the time, his new disciples were labelled as “crows”, and their “funereal shrouds” were billed as “Hiroshima Chic”, “Fashion’s Pearl Harbour”, he and Rei called “Rag Pickers”. Women’s Wear Daily pronounced the arrival of the pair in Paris as “a passing fad”.

But while their deconstruction of fabrics and finishings reflected a symbolic deconstruction of the past and its values, they also established aesthetic values that would colour fashion’s future: grungy teenagers and goths rifling through thrift stores; Belgian deconstructionists, such as Martin Margiela and Ann Demeulemeester; the countercultural darkness of Rick Owens and a generation of image-makers and designers who have archival Yohji pinned to their mood boards.

“Black is modest and arrogant at the same time. Black is lazy and easy and mysterious. It can swallow light or it can make things sharp. But above all, black says don’t bother me.” Yohji Yamamoto

Early on, Yohji began commissioning young photographers to create his seminal catalogues, shifting the look of late 20th-century fashion photography. Nick Knight, Paolo Roversi, Craig McDean, David Sims, Max Vadukul, and Sarah Moon immortalised his complex silhouettes in photographic form. Graphic designer Peter Saville began consulting on the visual identity of the brand, long before he became a regular at fashion houses in Europe. Today, Yohji’s work is beloved by fashion purists and hypebeasts alike, and his once-radical propositions of masc-femme, monochrome, and pre-loved materials have become commonplace across all strata of the fashion industry.

Despite his rebellious origins, he is now one of fashion’s few éminence grise – one of the last “masters” of the post-war generation. He has consistently challenged his own aesthetics and embodied delicious paradoxes that have made his work interesting and important for decades.

He has revisited Japanese dressmaking techniques, taken on the mantle of French haute couture, pioneered the fashion-sportswear crossover with his Y-3 partnership with Adidas, written memoirs and built several businesses, and trained generations of designers in his Tokyo atelier. All the while, he has never veered from his dignified design philosophy: complex, considered clothes that buck the convention of trends that the mainstream has to offer. He is proud that his work shows “a long obedience in the same direction”, words he adopted from Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. At 78, he’s not going anywhere but onwards.

To celebrate 50 years of Yohji Yamamoto’s fashion, we asked some of his friends, collaborators and fans to tell the incredible story.

Yohji Yamamoto graduated in Law from Keio University, Tokyo, in 1966, before studying at the prestigious Bunka College of Fashion under the tutelage of Chie Koike, a classmate of Yves Saint Laurent’s. Upon graduating, he worked at his mother’s dressmaking store in the “seedy Kabukicho area of Shinjuku”, in Tokyo’s red light district. Yohji described it as “A place overflowing with women whose job was to titillate male customers. They had shaped my image of womanhood since childhood and I was, therefore, determined to, at all costs, avoid creating the cute, doll-like women that some men so adore.” He won a scholarship to study in Paris from 1968 for two years, formed a ready-to-wear company in 1972, named ‘Y’s’, and showed his first collection in Tokyo in 1976.

Yohji Yamamoto: It’s hard to appreciate, unless you were born in Tokyo in 1943, when the war had destroyed everything: I, and this applies to a whole generation of Japanese people, have given up. I desire nothing, I want to be no one. Some people try to connect that to Buddhism, but that has nothing whatsoever to do with it.

Nathalie Ours (A partner at PR Consulting in Paris. She joined Yohji Yamamoto as PR Coordinator in 1987, after which she was PR Director in Paris until 2005.): He really started with nothing. I mean, with the support of his mother he started with a collection of coats, but in the first collection no one bought anything, but he kept on working.

Yohji Yamamoto: After graduating from university and finding myself without direction, I casually suggested to my mother that I help at her shop. She was furious. She had expected me to leave university and transition into a job at a fine company. She lectured me, insisting that if I was serious about the work I should at least learn how to cut cloth. I enrolled in a vocational school for dressmaking, and was jostled on all sides by women acquiring the skill in order to improve their marriage prospects: I spent my days tediously pinning fabric while pondering the question of what constitutes a proper profession for a man.

Kiko Kostadinov (A London-based menswear designer and collector of archival Yohji Yamamoto.): In Tokyo, those years are almost hidden years, because you expect that when they came to Paris, that’s when they started their companies. But actually both Rei and Yohji, and most of the Japanese designers of that time, were very well-established in Japan before that and they had solid businesses. You don’t really think, “Oh, he had a business for ten years.’ But they did, and they arrived in Paris after that.

In 1981, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo decided to show their collections in Paris. Although he already had a boutique in the French capital, he came there to present his first Yohji Yamamoto womenswear collection for AW81 under his own name. He caused a sensation with his masculine silhouettes, uneven hems, flat boots, and bare-faced models with covered heads, which appeared almost like widow’s shrouds. At once, the collection borrowed from both the canon of European workwear and tailoring, alongside the Japanese philosophies of wabi-sabi (imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete beauty) and ma (the interactive space between the body and cloth). It provoked an instant, if divisive, reaction.

Yohji Yamamoto: When I came to Paris, I remember the reaction as being so strong. I said to Rei that we are not souvenir designers. Japanese designers bringing Japanese ideas to Paris is not comfortable to me. I don’t want to explain Japan to the world.

Irène Silvagni (Having worked as a fashion editor since the 60s she left her position as fashion editor of Vogue Paris in 1992 and joined Yohji Yamamoto as creative director, where she worked until 2018. She passed away in March this year.): The first Yohji show I saw really threw me. It was like I was reading an entirely new book. It was really moving, I felt a shiver down my spine. It was like a siren went off.

Caroline Fabre-Bazin (Worked for Yohji Yamamoto from 1985 to 2003 as Worldwide Commercial Director, overseeing projects including the launch of Y-3.): When I saw Yohji’s clothes, I discovered another world. It was 1981, I was a student in Paris and I went to the Yohji store, which at that time was very tiny. The shop assistant invited me to the fashion show; the one called the “Hiroshima Chic” show by Libération. It changed my life and my vision of fashion completely. I was overwhelmed by the modernity of the women. I was really young in the business, and to me, it was an expression of the future.

Camilla Nickerson (A British-born, NYC-based stylist. She worked on visuals for this archival Yohji Yamamoto story with Mario Sorrenti.): I was “discovered” outside school and was asked to model Rei’s clothes. I was fifteen, and it was 1981 – the year they first hit Paris – and it was for an article on the Japanese coming to Europe. It was quite post-punk at that time, and you had it with the House of Beauty and Culture, Mark Lebon, Judy Blame, i-D had just started. What Rei and Yohji were doing was very similar to what was going on in Kensington Market: it was sort of counter to all the shoulder pads, and it was definitely trying to describe or speak to the underground. I think Yohji talks about the dark, the other side of the street. It was a very poetic time, even if it was punky.

Carla Sozzani (The founder of 10 Corso Como, and has worked with Yohji Yamamoto on various projects, including co-authoring his 2002 memoir Talking to Myself.): The arrival of Yohji was something that marked a big change in my aesthetic. It was something I recognised that I really wanted, but I didn’t know what it could be. Flat shoes, no make-up, not a big hairdo. It was the femininity of a woman coming out through what you are and what you feel. I didn’t feel aggressive. The “power” look was very popular at the time. But this was about strength in a different way.

Nathalie Ours: Yohji understood everything because he had this classical training. Yohji and Rei, they really invented new clothes, which were both Western and Eastern. It didn’t exist at all before. It was completely unique. And because of that he kind of created a Yamamoto school of making clothes, by training so many people in his studio.

Caroline Fabre-Bazin: It’s all about dignity, mystery, romanticism. He hates it when I tell him that it’s poetic because he has the feeling that poetry means weakness. I’m always trying to explain to him that it doesn’t. I made him read Baudelaire. For me, it’s all about the mystery in the woman, the dignity. It’s very noble.

Sarah Moon (A French photographer who contributed to editorials and catalogues on Yohji Yamamoto.): Of course, his taste and talent show that he is a real couturier: the passion, the persistence to combine weight and lightness. His independence and perfectionism, not following trends, and constantly evolving and inventing new textures and materials – mostly in black.

Angelo Flaccavento (An Italian fashion critic. He attended his first Yohji Yamamoto show in 2006 and hasn’t missed one since.): The crinkled cupro and the nomadic shapes of AW84 are one of my most vivid personal memories: the moment in which, barely twelve, I fell in love with Yohji and the Japanese. I was taken by the abstraction and the somberness they came to represent within the decade that taste forgot. They were the exact opposite of all the glitz, the glamour, the flash, the cash of the 80s.

“What is authentic takes place in the shadows.” Yohji Yamamoto

Caroline Fabre-Bazin: When I was working with Yohji, I would see all the people working for him, it was like an army. Crows are very dark, and often it was said with a bad meaning, but it was not that at all. Black is a very strong colour. In the 80s, there were a lot of people that were calling themselves gothic. Yohji is not that at all either. When you wear Yohji, you don’t need to have many accessories. You don’t need to wear make-up or have a very strange hairstyle. It’s all about the clothes.

Yohji Yamamoto: Black is modest and arrogant at the same time; black is lazy and easy – but mysterious. It means that many things go together, yet it takes different aspects in many fabrics. You need black to have a silhouette. It can swallow light or make things sharp. But above all, black says… don’t bother me.

Terry Jones (The founding father of i-D. He became friends with Yohji Yamamoto in the 90s and authored the Taschen book on the designer in 2012.): The fashion industry and everyone that was working in it all started wearing black. It became the uniform. He was looking at black in a totally different way as a colour that has so much diversity. I think that was the thing which Yohji was very strong on – his fabrications and the different types of fabrics – and the way light would affect the different textures really showed black in its full diversity.

As a person, Yohji is not what you’d expect from the seriousness of his clothes. Standing at just over five feet tall with a lithe frame, he is a gambling, smoking, pool-playing, whisky-drinking, guitar-strumming ladies man who drives a Rolls Royce. With his goatee-bristled smile, his mischievous sense of humour can often be found in his collections, layered beneath the sober tones and heavy layers.

Yohji Yamamoto: It’s very easy to talk about serious things in a serious way, but wouldn’t it be much more difficult to express profound sentiments and thoughts in a light-hearted and radiant tone? Comedies are always more complex than tragedies.

Marc Ascoli (A Paris-based art director, who worked with Yohji Yamamoto from 1983 to 1987, and then again from 1995 to 2003, commissioning seasonal photographic catalogues.): He reads a lot and is inspired by poetry, but he’s also a man: he smokes constantly, he’s a womaniser.

Terry Jones: When he did his first show in Paris for Y-3, it was in a sports arena, and at the end of it, Yohji had a few drinks and a big cigar and looked like the owner of a football club. He was utterly brilliant. It was not the stereotypical image that one has of a fashion designer.

Tim Blanks (A London-based fashion critic who has covered Yohji Yamamoto’s shows since the early 80s.): When I got to know Yohji I began to understand just how obsessed he was with the bohemia of the West: the Beats, jazz, Miles Davis, all of that… His voice was quite distinct from his peers. I think of Issey Miyake as being absorbed by the intricacies of Japanese culture, and Rei finding some common ground between Japanese Edwardiana and London punk. But Yohji turned an eagle eye on the influence of American culture on Japan, so what he brought to the rest of the world was an alien perspective on an alien culture. He’s a masterpiece of counterintuitivity.

Irène Silvagni: Yohji says that fashion is the language that he speaks. And in some strange way, his clothes seem to come right out of his soul, like they’re filled with all his emotions and strengths. Yohji is a hard man to really get a grip on, I call him ‘the eel’. His clothing, though, always seems to have an honesty about it.

Angelo Flaccavento “I was born to be poetic,” Yohji told me backstage after the SS20 show – his nth, enchanting foray into flowing elongation. The sentence was followed by that knowing grin he uses to seal his speech, a quiet form of provocation. Yohji always brings things down with a sardonic smile and long, telling silences. The work is poetic but the man is a provocateur.

Rachel Tashjian (Fashion News Director at Harper’s Bazaar in New York, and a longtime fan and customer of Yohji Yamamoto.): I first came across that book, An Exhibition Triptych, when I was in the store in Paris, six or seven years ago. There was this line that said something like: “Many consider Yamamoto-san a minimalist, however, he likes to smoke and drink to excess.” I thought that was so fun. I mean, yeah, of course he’s not a minimalist. He loves life! He’s a glutton, in a certain way.

Terry Jones: Each time you would meet Yohji you would learn more about him: how his mother was a post-war spinster after his father died in the war, how he would watch her dressing women who worked on the street. She was like a couturier for the women that would come to the house and have custom-made dresses. That stayed with him; his love of women and their strength came from that period in his life.

Yohji Yamamoto: I am the only son of a war widow – since the time I was four or five years old, I have seen the world and society through the eyes of my mother. It is tough for a woman to raise a child, to work and to live all by herself, compared to a man living alone, especially during the period when I grew up. To say in the extremes, all men are my enemy, taught through my mother.

Rachel Tashjian: The clothing is incredibly beautiful and really smart and also funny, that’s what really resonated for me, this very elegant sense of humour that you really don’t see in fashion. The kind of obfuscation that the clothing creates, it’s never reallystraightforward. But I find it to be very warm and inviting as opposed to a lot of other avant-garde fashion, which can be quite intimidating to someone who might encounter you on the street.

Yohji’s clothes are not for the faint-hearted. Invoking a devotion that often veers into obsession, those who discover his clothes often become lifelong customers. For them, the clothes provide an egalitarian uniform where black is the common denominator and the intricacies of each garment offer as much private joy as public display.

Tim Blanks: Speaking as a male client of Yohji’s, it is too obvious to say that Yohji pioneered generously sized clothing for generously sized men who wanted to be fashionable. Or maybe it isn’t. His work has stood the test of time because it has a dark poetry that appeals to the dark poet in every otherwise ordinary individual. It’s hard to believe it’s been half a century because it has been so remarkably consistent. In a perverse way, evolution has scarcely been its point because Yohji has been nothing but true to himself, it is fashion design as autobiography.

Camilla Nickerson: It’s about finding beauty in the imperfect. That creates vulnerability and then it allows you to feel something. That’s really artful.

Caroline Fabre-Bazin: In Paris, we had a different way of wearing it. I was always telling the team: don’t forget that in Europe, when we put on a jacket, we always move the shoulders on the front, but the Japanese way is on the back. Because the back of the neck is the most erotic part of the body in Japan – which is why kimonos go back. So, you can wear a Western jacket in a Japanese way. This mixing is super interesting, not only for the look but also in the way the clothes are built.

Rachel Tashjian: Yohji has always stood for connoisseurship in fashion and aesthetics: it’s clothing that requires you to look carefully to understand what it is. If you pause and take a moment to really look at what this person is wearing, you’ll be really delighted and perhaps even more confused: How is that lacing up? How is that skirt buckling? Is the hem supposed to be asymmetrical? Or is it just the way that this person is walking? I really can’t think of any other designer who creates with that level of joy and curiosity.

Angelo Flaccavento: As an expert pattern cutter who listens to fabric, so to speak, Yamamoto has kept innovating from the inside, oblivious of passing trends and fads. He is no flash in the pan; his ideas are built deep down, inside the seams of every piece that bears his label. Repetition is an essential tool of the Yohji language, even though, looking at the whole of his oeuvre from a historical perspective, one notices weaves and changes.

By the early 90s, Yohji had been joined by a generation of designers borrowing from his trademark sobriety and deconstruction. So, he began to evolve his look, becoming more experimental than ever. By the end of that decade, as a new generation of predominantly Britishdesigners took over the gilded salons of Paris’ couture houses, Yohji staked his own claim to those positions with couture-like collections comprising sculptural origami-like gowns, ornate details, and homages to Christian Dior’s New Look, Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking, and Chanel’s tweeds and pearls. “You want haute couture? Here it is! It’s not hard,” he was quoted as saying in 2001. Ever the contrarian, he began to play with the very glamour he rallied against when he first arrived in Paris. And he did it better than many couturiers.

Yohji Yamamoto: If I was a fine artist or something, I could decide for myself when I start creating, but in the fashion world the scale is already set. You have to adapt. You are forced to adapt, and every time, every season, the theme of my collection is always against something. In 1997, I did the collection as a paradox about haute couture. Sometimes I started to think about whether I should deny my past creations: maybe I should break my taboo, so I can try a kimono in a collection, or do all wedding dresses in one show. I always want to go against something, some trend, or some movement.

Tim Blanks: Rumours were circulating for a while that Yohji was a candidate – or at least auditioning – for the job at Dior that John Galliano eventually got. This presentation clarified for the world what Dior missed out on: although Yohji offered another wedding show a year earlier that was equally emotional. He has always had a very adept hand with key rituals, turning points, and moments of revelation.

Yohji Yamamoto: I’m the last classical designer who studied real French couture. Great stars such as Pierre Cardin and Yves Saint Laurent have been my teachers. The young fashion designers following us in Tokyo don’t study couture, they study art. They’ve never really learned how to sew, how to cut, or how to press a pattern.

Camilla Nickerson: I remember going to the wedding collection show in 1999, and I cried. It was really emotional.

Rachel Tashjian: There’s a moment in one show where a woman comes out in this beautiful, very simple silk dress with a hoop skirt, and you think, oh, that’s really beautiful. Then she pauses in the middle of this square runway and begins unzipping unseen pockets within the hoop skirt and putting on a silk robe. She puts on a pair of flat sandals and a hat and the outfit is transformed into something much more formal, but seemingly impromptu, which is a pretty sophisticated joke actually. What are the possibilities of clothes and what do these kinds of uniforms signify? The bride is usually being super serious, like, “Oh my God, this is the most important thing I’ll ever wear!” He kind of turns that on its head by asking – what if you get halfway down the aisle of life and you decide, I don’t really wanna be like that?

Yohji Yamamoto: This time I was interested in the wedding dress, between real life and costume. I found so many stories behind the wedding dress situation; wedding dress and widow dress, two sides of the same coin.

Nathalie Ours: There have been so many different chapters in his work. The first one was really about construction and asymmetry. Yohji was also fascinated by French couture, and you really see that in the Nick Knight catalogues. There was his whole experimental moment in the early 90s: you can’t really say it was moving in one direction. Then, in the mid-90s there was the arrival of Irène Silvagni, a creative director and an inspiration. Yohji was extremely inspired by her. There were homages to Chanel’s tweed suits, Dior coats, and Cristóbal Balenciaga, but it was in the Yamamoto way. One thing Yohji would often say is that he’s always singing the same song, only in different arrangements.

Yohji Yamamoto is often called a ladies’ man. Having grown up with a single mother, the formidable Fumi Yamamoto, who would later sit in on his fittings and accompany him to Paris. Yohji has said it was she who, dressed in dark mourning clothes throughout his childhood, first “awakened him to sobriety”. The interplay between masculine and feminine, like Saint Laurent and Chanel before him, became a central tenet of the duality of Yohji’s clothes. He recalled how he was inspired by old French war movies starring actresses in military uniforms: “I found that so sexy. The body is protected, and covered, in a very hard way. So you are forced to ask yourself, ‘What’s inside?’ When you have no freedom, your sexuality becomes stronger.”

Yohji Yamamoto: I always hope to make people think about life through clothing. I started watching society through women. Women are everything to me. I hate them, detest them, I love them and respect them and I am very concerned about women. I decided to work in fashion with the sense that I could help protect women from many dangerous circumstances.

Irène Silvagni: Yohji and Rei changed the way of being sexy and sensual, the way of being well dressed – for women and for men, because it was an extraordinary revolution for men.

Carla Sozzani: Everybody can wear Yohji. It’s not a matter of shape. The clothes are quite egalitarian. No matter your age or size, you look feminine and elegant. You feel secure. And when you feel secure, you are more beautiful.

Irène Silvagni: He’s kind of like Yves Saint Laurent. They have a lot in common. They understand what it’s like to suffer, they see drama in life, and they both really love women. They never seemed like they were playing around with cutesy women like they were dolls or something. You just wouldn’t find that kind of woman in the shows.

Yohji Yamamoto: Dolls… This is what many men want women to be… just dolls.

Rachel Tashjian: Isn’t great sex about trying to make the other person feel good? You know, it’s funny, we have so many male designers and so many of them are thinking about just their own egos. I think in some cases, if you are someone who is obsessed with women in a less pathological way then you can really think about what she might want, what would she want to be seen in? It comes from a sense of empathy, I think.

Yohji Yamamoto: In my philosophy, the word androgyny doesn’t have any meaning. I think there is no difference between men and women. We are different in body, but sense, spirit and soul are the same.

Often our memory of fashion is in fact our memory of fashion photography. From 1983 to 1987, and then again from 1995 to the early 2000s, Yohji Yamamoto worked with art director Marc Ascoli on commissioning his seasonal catalogues using both established names and the emerging photographers of the time. Nick Knight, Paolo Roversi, Craig McDean, David Sims, Max Vadukul, and Sarah Moon all contributed, as did Peter Saville, who was responsible for graphic design. The result of these collaborations was every bit as groundbreaking as the clothes.

Marc Ascoli: Freedom. I can say this word. No marketing or anything like that, you understand? He gave me the keys to the car. I was completely responsible from day one. He was not questioning me. It was really simple.

Sarah Moon: We don’t speak the same language, but it didn’t stop us from communicating. I totally respect his work, I think he respects mine, and that allows complete trust. It amazes me when I photograph his clothes to see the continuity and the differences in the shapes, structures and architecture.

Angelo Flaccavento: Yamamoto understood very early on the power of the image, and the necessity to be open to new ways of doing business. The catalogues he produced are unique feats of image engineering and visual storytelling. They are still landmarks that the fashion system constantly refers to as unbeatable specimens of touching modernity.

Camilla Nickerson: Japan helped to expand the creativity that was coming from elsewhere. It was very a mutually beneficial relationship that validated what was going on separately in each place. Japan, at that time, was very generous. We were all broke and starving, and they would pick us up off the street, put us on a plane, and we’d all fly over there to be in their fashion shows.

Carla Sozzani: What the photographers – and Marc Ascoli, because he chose the right people – did was interpret a new vision of women. It’s one of those situations where you don’t know where the photography starts and the clothes begin.

By 2009, Yamamoto’s empire encompassed seven lines: Y’s, Yohji Yamamoto, Noir, Y Yohji Yamamoto, Y’s Mandarina, Coming Soon, and Y-3: a pioneering democratic fashion collaboration with Adidas. “Fashion had become so boring,” Yohji told i-D in 2016. “I felt I had come too far from the street. I couldn’t find people wearing my clothes anymore and I felt so lonely. At the time, New York businessmen were starting to walk to work in their suits and sneakers. I found this strange mix incredibly charming, a fascinating hybrid.”

Angelo Flaccavento: Y-3 merged sport and fashion when it was completely unusual, and highly risky, to do so.

Terry Jones: It was a shock to a lot of people when he partnered with Adidas. It could have been seen as selling out, but actually it was the start of so many designers producing collaborations with sportswear and streetwear brands. He was the first, and I think that brought aspects of his signature to the masses.

Nathalie Ours: He saw so many young people wearing Adidas and he thought, ‘I need to do something with those three lines’. It was the first of its kind. It was unique to have a creative fashion designer doing a full line with a sportswear brand. Yohji was happy about that because it connected him to another generation.

Ligaya Salazar (A fashion curator, responsible for the seminal Yohji Yamamoto retrospective at the Victoria & Albert museum in 2011.): Yohji, for me, has always been the most prolific collaborator within the fashion world, and a very generous collaborator too; both with people who worked on his imagery, with filmmakers and all sorts of other creators, from Adidas to Pina Bausch to Wim Wenders.

Now 78 years old, Yohji is still designing. Having overseen over 500 collections during his career, younger designers look up to his lasting endurance and lifelong commitment to a singular aesthetic. Never wavering from his poetic outlook on clothes, the intricacies of their construction and the stories they convey, this year he celebrates the 50th anniversary of starting his first business – all those years ago in Tokyo.

Yohji Yamamoto: Culturally, I don’t think I’ll leave a mark on anything in the history of what is beautiful, or even in fashion history. Yes, I am close to thinking that only things that are inauthentic leave traces; by definition what is authentic takes place in the shadows. If you look for signs of what mattered in the 70s, you’ll see no mention of my creations in fashion and art. I say this without bitterness.

Angelo Flaccavento: Without him there would have not been deconstruction, nor Belgian conceptualism, that’s for sure. Yohji put emotions front and centre in his work, and did away with status, sex and bling.

Kiko Kostadinov: There’s not many independent designers these days. So to have him and Rei still working, it’s very refreshing. Perhaps Rick Owens is the closest to them, in terms of owning the company, doing what he wants, having a signature and a loyal customer. Everything else is just a part of the system. I don’t know how long we have left. But Rei and Yohji, they’re not even in their 80s yet.

Angelo Flaccavento: There is something heroic about him. Endurance is what makes Yohji a hero. A fashion hero, in the same league as Giorgio Armani. Yohji has carved his own niche, which he confidently inhabits, never looking for approval or validation from others. The system has not always been on his side, but Yohji did not care. Masters like him are made of special matter, and you have to be in order to sit above the trifles and minutiae that are so desperately essential elsewhere. Because of this, Yohji’s avant-garde status has quickly turned into pure classicism. True modernity, after all, is timeless.

Kiko Kostadinov: I think we’ve taken it for granted that he exists. Yohji shows are not as popular as they used to be. There’s just so much other stuff that you end up being pulled towards. But it’s still an amazing thing to see in person.

Rachel Tashjian: There’s a really unfortunate thing happening right now in fashion, where there are three brands that everyone pays attention to. And these three brands are a little bit of a circle; pretty much everyone pays attention to the same three brands and that’s what we care about. If you’re not in that mix, then people don’t pay attention to you. I can’t stand that. It’s very upsetting because it means that people don’t care to write or read or think about what other designers are doing, because the measure of success is relevance, and what we really mean by that is marketing. That’s horrible, especially if you are a person who loves thinking and who loves beauty.

Nathalie Ours: He stayed really true to himself over the decades, with new designers coming through with new ideas, new trends, new media. I remember Dries Van Noten saying that when he was starting out in Antwerp he was worried about using his own name because it’s so complicated. Then he realised: if Yohji Yamamoto made it, then why not him?

Rachel Tashjian: Now, everything is designed to be understood by everyone. There is no comfort with ambiguity, and there is very little comfort with things that are just for you and your own feelings. Everything is meant to be shared or exposed to everyone else. And these are clothes that stand for privacy, delight, elegance, and joy. And I can’t think of any qualities that are more essential to life.

Caroline Fabre-Bazin: A lot of designers today are completely stressed and panicking about the age of their clientele. They really want young people. But you can dress all generations without claiming that you just want to dress young people, and Yohji gives a kind of lesson in that you can wear his clothes and you can be beautiful at 15 and at 70.

Carla Sozzani: I still believe that this is just the first 50 years. I expect to see many more years of creativity. It can go on forever because he takes inspiration from his own work. It’s endless.

Yohji Yamamoto: Very often I feel I’ve done almost everything. Then the next question to myself is: “Why are you continuing the same thing?” A very childish answer comes back: “Because I love clothing.” And each time I’m working for the next collection, next season, during fitting, during cutting, each time I find some invention. That is the moment when I feel happy.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.

Credits

Photography Mario Sorrenti

Fashion Camilla Nickerson

Hair Bob Recine

Make-up Frank B at The Wall Group

Nail technician Honey at Exposure NY using Zoya in shade Naked

Photography assistance Kotaro Kawashima and Brett Ross

Digital technician Chad Meyer

Fashion assistance Joséphine Dorval, Imaan Sayed, Andy Planco and Emma Parr

Hair assistance Le’kema Allman

Make-up assistance Natuska

Production Katie Fash, Layla Néméjanski and Steve Sutton

Production assistance William Cipos

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING

Model Anok Yai at Next

All clothing YOHJI YAMAMOTO