It’s just an apple. Well, it is and it isn’t. The first piece one encounters in Yoko Ono’s new/old show up now at the Museum of Modern Art is a fresh, shiny Granny Smith on a Perspex pedestal. Just like the one John Lennon mischievously bit into at London’s Indica Gallery in 1966, launching one of art and pop culture’s most meaningful relationships and collaborations.

Sitting at her kitchen table fifty (!) years later, Yoko tells me, “Apple’s a very unique piece. It’s still unique. I don’t think anybody is doing fresh fruit as an object. At the time some people laughed about it. But John took it very seriously – he took a bite. I took it even more seriously. I thought, ‘He shouldn’t be doing that! Stop it!’ But I didn’t say that. I was just looking very angry. And he noticed that and put it back on the pedestal. It was really amazing.”

“It’s a kind of memory land, memory lane, about the fact that he reacted that way, the fact that I reacted that way,” she continues. That’s Yoko today, at 82: honest, open, and reflective about the past. I hadn’t planned on asking about John. It felt invasive, and anti-feminist somehow, to focus on her famous partner, however present he may be. Arriving at the Dakota on the Upper West Side for our interview, I had to push past a tour group snapping cameraphone pictures of the building’s entranceway where he was tragically killed.

But the topic of her late husband comes up naturally, and Yoko’s ability and willingness to meld the past and present is notable. And contributes to the genius of this particular exhibit, ‘Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971.’

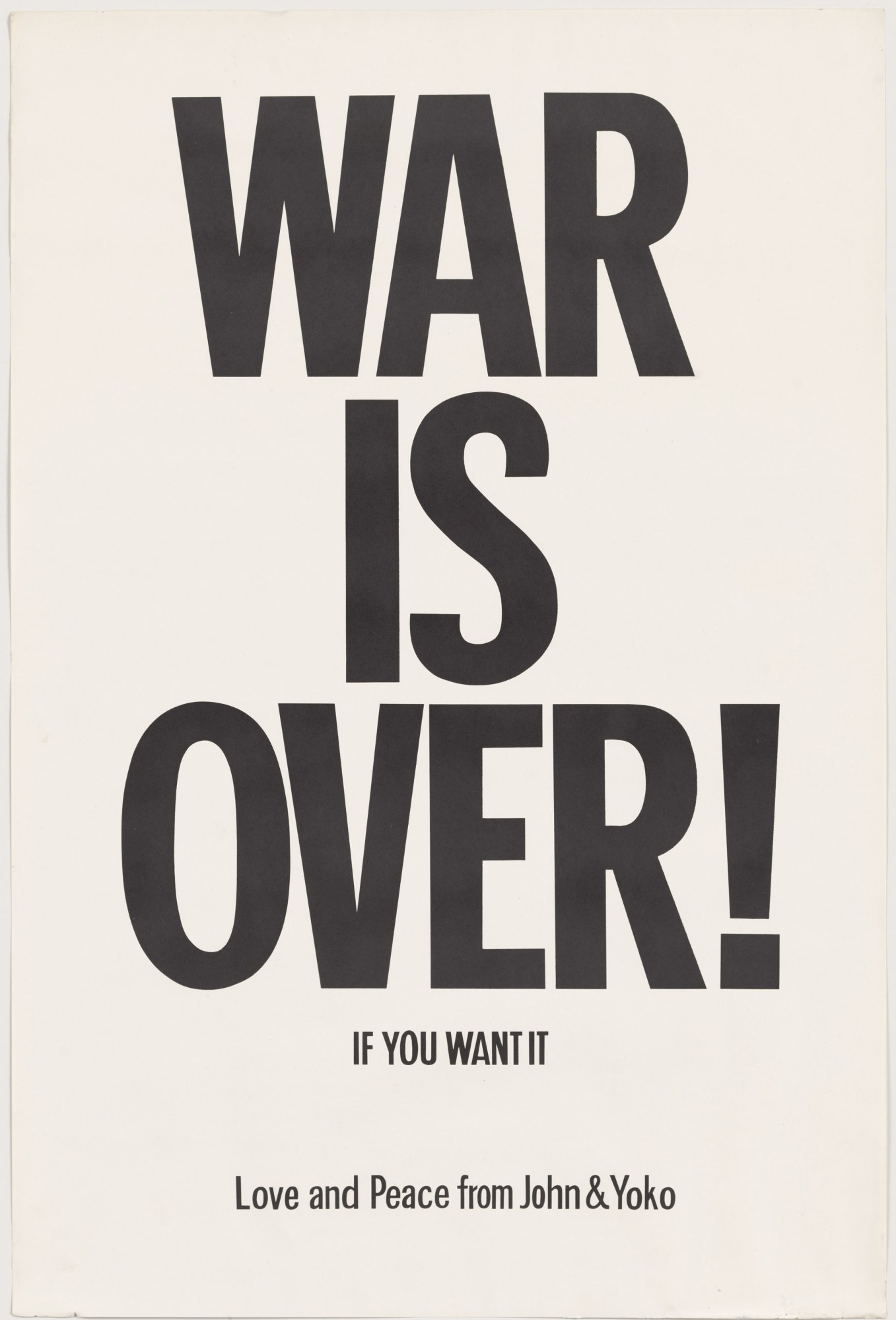

In 1971 the revolutionary young Japanese artist staged a rogue exhibition “at” the then-stodgy MoMA. Called ‘Museum of Modern [F]art,’ the conceptual show featured a sign saying that Ono had released flies on the museum grounds and viewers could chase their journey. “I thought it was fun,” she says today. “It’s just a joke in a way. A big joke.” A video of the happening shows a young bespectacled man asking bourgeois New York museum-goers what they think about the work. They seem confused yet intrigued. So it worked.

MoMA curators Klaus Biesenbach and Christophe Cherix came to Ono with the question: What if we staged a retrospective based on the years preceding the experimental happening? In other words, what if the museum had been prescient enough in 1971 to give her a proper show? As she says, “In those days women artists were a no-no, and there were no Asian artists. They weren’t thinking about me.”

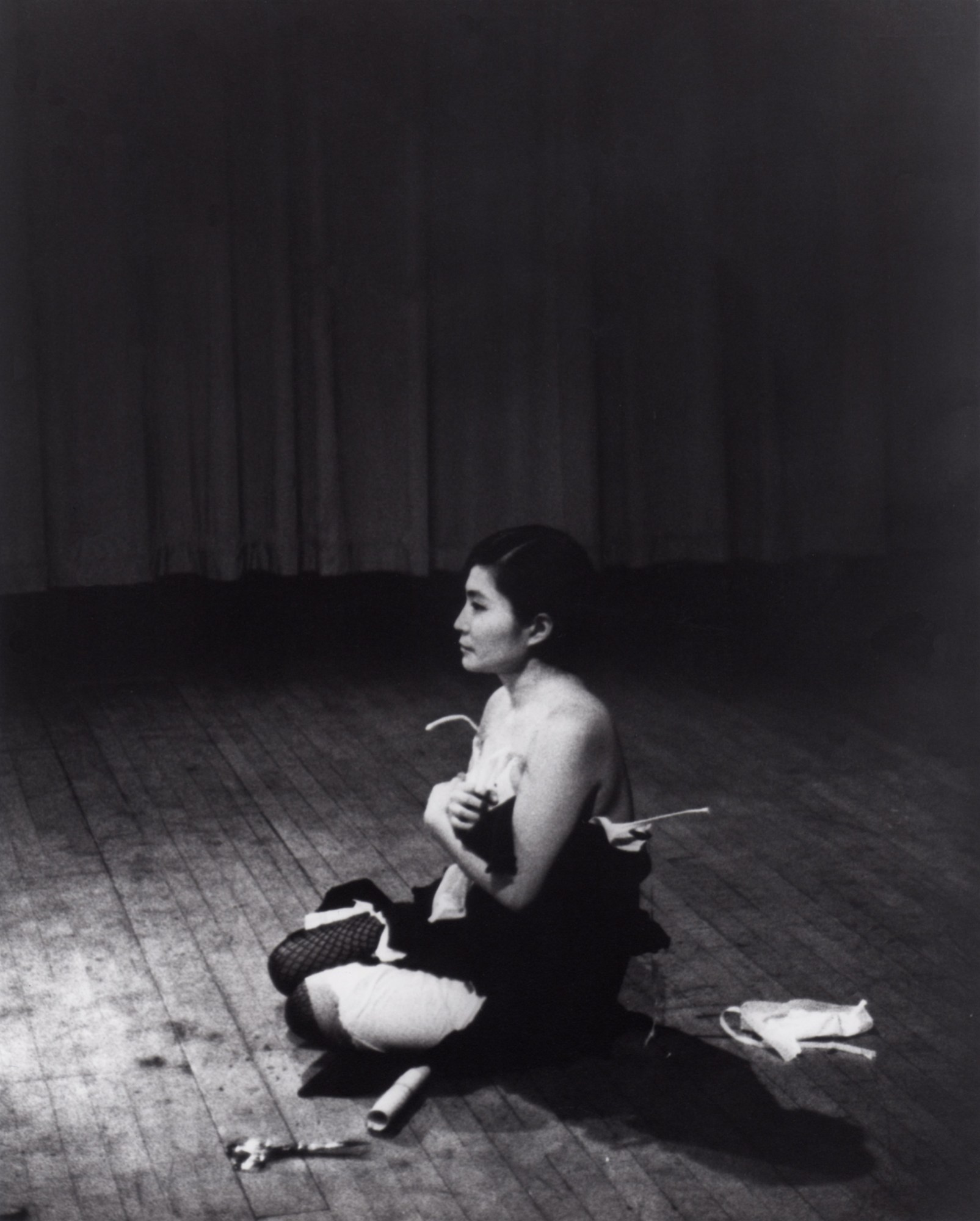

“They” are now. As are the hoards of fans lining up to see the powerful exhibit that features many of the works Ono is best known for, like Painting to be Stepped on (1960/61), all the stirring instructions of Grapefruit (1964), and videos of performances like Cut Piece (1964). She thought it was interesting – in a good way – that the museum chose to show only 11 years of her 60 plus years of work, including twenty albums, peace protests, public artworks, films, and objects. “The small slice can expand to large imagination,” she says.

Ono sees her 1971 conceptual show as a self-actualizing dream for the current one. “I’m trying to suggest what you can do to create what you want to create,” she says. “How to do it.”

Her work is often about that very power of suggestion, of possibility. The simplicity of the Grapefruit instructions conceals their power. Think of the Beat Piece from 1963: “Listen to a heart beat.” Or Earth Piece, also from 1963: “Listen to the sound of the earth turning.” Incidentally, she gave me a new (golden!) instruction for i-D readers: “Make your own instructions.”

When I ask her whether the videos of her performance pieces can make viewers feel like they were there, she says, “Well, it depends on the person. Some people are very imaginative, and they don’t even have to see the whole Cut Piece. It just says Cut Piece, and they go, ‘A-ha!’ And some people can see the whole Cut Piece and still not understand it.”

One of Yoko’s superpowers is her ability to make us rediscover the simplest things around us. We talk about the roundness of several elements in the show: apples, grapefruits, the buttocks in the mesmerizing Film No. 4. “All round! I didn’t think about that. But the sun is round and the moon is round,” she muses. And why butts, in fact? “That is not just round but it has a movement, a kind of complex movement,” she responds. “There are four sections, and each section moves differently. It’s incredible.”

It’s no accident that the show is called ‘One Woman Show,’ playing with the legacy of millions of ‘One Man Shows’ in museums throughout art history. Ono’s feminism runs deep: “I love all women. And it’s a very strange thing to say. Because it sounds like a very tactful political statement. No! The reason that I’m starting to love each woman is that women suffer so much. Each one. And they’re still alive. And I marvel at the fact that they’re still going on. Each one is so brave.”

We’re vibing enough at the end of the interview that Yoko humors me and plays a word association game:

Apple: “Orange”

Grapefruit: “Very beautiful.”

Sex: “It’s very complex.”

Woman: “I love them.”

New York: “I have been here for such a long time that it’s part of me now.”

War: “Oh my God! Well, let’s put it in the closet and close it.”

Peace: “We’re gonna have it one day. I think that it’s very important that we believe in it.”

Love: “Love is the force for everything.”

As I’m leaving, I look back at Yoko, wearing her signature dark shades and hat in her cheery yellow kitchen. She lifts her arms and shouts out, “Spread the word!”

Credits

Text Rory Satran

All images courtesy The Museum of Modern Art