In the ever-evolving realm of fashion, definitions are slippery. For example: what characteristics differentiate a piece of jewellery from a piece of clothing? It seems as though both categories exist — and, perhaps, have always existed — as mutually exclusive entities. But when you hold them up side by side, these seemingly well-defined boundaries begin to shift. Perhaps the distinguishing factor between jewellery and clothing is purpose (the former, functional; the latter, decorative), body placement (is there a name for jewellery donned on the shoulders?) or the way it’s worn (to my knowledge, clothing doesn’t pierce). On the other hand, some might differentiate jewellery and clothing by the materials they’re made from: metals, jerseys, plexiglass, gabardines, stones, denim. If jewels are hard, and garments are soft, then does a breastplate by Issey Miyake, Tom Ford or Ludovic de Saint Sernin, read less as a corset and more as some sort of newfangled necklace? And what about the chainmail dresses and jumpsuits of Paco Rabanne? When it comes down to it, it seems like these two categories aren’t so different after all.

Blurring the boundaries between the two even more, a new group of jewellers are creating what can only be dubbed as “hard-wear”: hybrid designs that exist at the nexus — the very center of the Venn diagram — of clothing and jewellery. Through these hard-edged, garment-like designs, Lorette Colé Duprat, Juanita Care, Marland Backus and Frances O’s Emma O’Farrell are broadening the definition of what jewellery can be and adorning often overlooked body parts in their extravagant, innovative pieces.

Lorette Colé Duprat

In tandem to designing jewellery for Casey Cadwallader’s Mugler, Parisian designer Lorette Colé Duprat creates convertible accessories that bring second-life to their wearer’s wardrobe staples.

How did you develop an interest in fashion?

Fashion has been in my mind from a very young age, unconsciously. My mom told me once that, as a kid, I wanted to play a lot of sports, not especially for the sports themselves, but to wear the uniforms and equipment: the helmets, the plastic protective gear. It was all about dressing up. So, as an adolescent, I thought I wanted to be a stylist, but during my studies at the Design Academy Eindhoven it became very clear that I wanted and needed to be a designer, in the infinite quest for new concepts.

What’s the concept behind your “Freed” accessories?

“Freed” is a hybrid collection of acrylic belts and accessories that offers an alternative to buying new clothes. They can be positioned freely on the body and are held in place by the tension created by the surrounding materials and garments. These rigid and flexible interactions allow the wearer to modify the appearance of a garment without altering it. For example, a shirt becomes a skirt, a set of scarves transforms into a crop top. Used more discreetly, these pieces can also act as a belt, adjusting oversized trousers or a simple secondhand shirt. These structures give a second life to garments. They also give the wearer a set of tools to become the master and to create: to play with their style and to renew garments without consuming.

What about your beaded necklaces?

The necklaces are also meant to be worn in several ways. Thanks to their clasps, they can be connected to each other becoming a harness that snakes around the body or a belt.

Do you consider your pieces to be jewellery or clothing? Or both?

I consider them to be multi-functional accessories rather than exclusively jewellery. But not clothing. Sometimes I like to make a top or thong in metal, but it’s not the main purpose of the piece.

In your opinion, is there a distinction between the two fashion categories?

To me, for the moment, there is a distinction to be made between jewellery and clothing because one can’t replace the other. Rather, they’re having a conversation and are interacting with each other.

How does the body inform your work?

The body’s like an endless playground. It’s an endless source of exploration: how it’s articulated, how it’s hard and soft at the same time. Working mainly with stiff materials, the body’s a daily challenge to work with, to find new ways of embellishing it, new unexploited zones.

You can buy Lorette Colé Duprat’s piece online at APOC and Auné.

Juanita Care

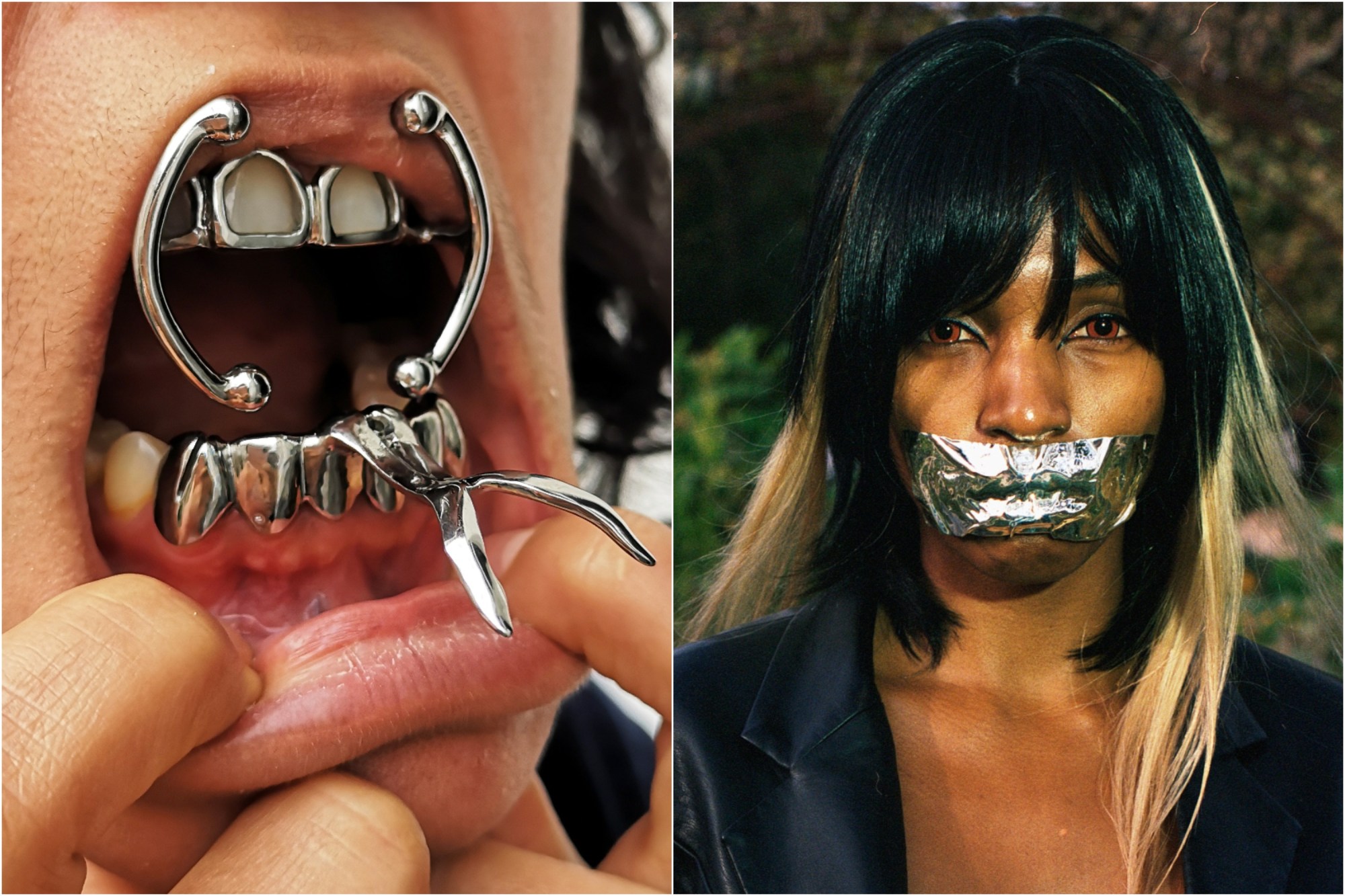

Based in Marseille, French-Peruvian artist and designer Juanita Care creates jewellery for the most intimate body part: the mouth.

How did you start designing jewellery?

I got into it a bit by chance. When I came out of studying fine arts, my intention was to find a compromise between continuing to make art and being able to sell my work, simply, without going through galleries or exhibitions. When I met a dental technician, Thierry, something clicked and I thought I would try to create jewellery for teeth.

How do you define jewellery? What makes it different from clothing?

Jewellery is a very special object that has a close connection with the body. This closeness also exists between the naked body and the clothing, but jewellery goes further in this relationship, since we sometimes go as far as modifying the body to accommodate them. To pierce the ears, the nose, the nipples, etc. In my case it wasn’t a question of modifying the body, if not to make custom-made jewelry that fits the body perfectly.

What drew you to creating jewellery for the mouth, specifically?

The mouth seems to me to be one of the most intimate parts of our body. It’s the place of a whole social and cultural construction. It is a place full of meaning and symbolism. It is here that the words and the languages are born, it is here that food comes in, that aggression manifests itself, that love and sex are practiced. But it also tells us a lot about our health, our social class. Those who can redo their teeth, those who whiten them, those who cannot. It is the place of identity, since precisely our teeth can be used for the identification of a body, because they are extremely solid and above all unique.

Oral jewellery remains very marginal. It’s experiencing a certain success with grills, but it is a field of jewellery that is very poorly developed. And thus only for that it is interesting to look into the question.

How does wearability figure into your design process?

I distinguish two categories of jewellery in my work. The first is the manufacture of dental jewellery, commonly known as grill jewellery. In this one the question of wearability is very strict. It’s important that people feel comfortable with the jewellery, that they can speak without discomfort, that it’s not too bulky. The second is the more artistic part in which the question of wearability is not really the subject, but the custom-made character.

Could your pieces exist as autonomous works, without being related to the body?

Yes, this is something that matters to me. I see them as small sculptures. In most of the pieces that I have done alone or in collaboration with other artists and designers, the presence of the body is always there, inscribed in the piece by the presence of the imprint, be it teeth, palate, lips or other. So yes, these objects are still there and I like to show them that way even when they are not worn. On the other hand they always suggest the body of their owner.

You can commission a custom Juanita Care piece through the designer’s website.

Marland Backus

A graduate from Pratt Institute’s industrial design program, Marland Backus creates jewellery to highlight the body parts that are oft overlooked.

How did you get into fashion and design?

I never intended to wind up in the fashion world. I always had an interest in fashion, but never thought of it as a profession. I actually went to Pratt Institute for industrial design and focused mainly on tableware and furniture design. In senior year, I found myself using the materials meant for furniture and tableware to make jewellery. At first it was just a hobby, but then people kept asking to buy it so I eventually turned it into a small business.

What’s the concept behind your body pieces?

I think just accessorizing the neck and wrists is too limiting. I think there’s a lot of body parts that get overlooked.

In your opinion, is there a distinction between jewellery and clothing?

To me one of the main distinctions is the material. But I think it’s really interesting when you approach that line between the two and start making things like metal clothing or beaded clothing.

How does the body inform your work?

When I design jewellery I’m always thinking about the body. I love pieces that interact with the human form. I think the human form is beautiful and I want to make jewellery that accentuates that. For instance, one of my new pieces I designed so that it sits perfectly in your jugular notch. There’s something really satisfying about it. I also love to highlight the parts of the body that don’t get a lot of attention, such as the shoulders.

Could your pieces exist as autonomous works, without being related to the body?

The body chains I’ve designed can only exist with the body. When not being worn they’re literally a pile of chain. But that’s what’s so special: that you need the human body to bring the pieces to life.

You can buy Marland Backus’ pieces online at the designer’s webshop, APOC and Café Forgot.

Frances O

Crafted in the UK, Emma O’Farrell’s jewellery-clothing hybrids are inspired by 90s supermodels and Ibiza nightlife.

How did you get into designing jewellery?

After leaving school I went on to study fashion design [at UCA Epsom], which gave me the initial foundations to take those first steps into the industry. Upon moving to London, I began working with large high street fashion brands, but became bored rather rapidly of their commercial and unethical work practices. I decided to move on to a smaller gallery brand, which is where I developed my eye and passion for all things metal! Here, I was given creative freedom and re-energised my love for design. This is what ultimately gave me the final nudge and confidence to start Frances O in 2019.

What’s the concept behind your pieces?

Growing up in the 90s, I’ve always had an utter fascination with the catwalk and designs of that era. This period was also the absolute height of everyone enjoying the rave scene in Ibiza. I was fascinated by articles and pictures in magazines of all the fun going down on the White Isle.

Merging these two influences of the 90s and Ibiza with my love of modern art, I came up with the Frances O concept. It was also important for me to produce a collection that was both produced solely in the UK, and made to order, so as to limit waste and place focus on truly everlasting pieces.

Would you consider your pieces to be jewellery or clothing? Or both?

My pieces are anything anyone wants to interpret them to be. A jewellery-clothing hybrid sounds just darling to me!

To you, is there a distinction between the two fashion categories?

In my mind, any and all garments whether that be jewellery, clothing or accessory, create an identity for the individual wearing it. That identity provides unity, a wholeness, totality.

You call your designs “wearable art.” Could your pieces exist as autonomous works, without being related to the body?

Totally. I am a huge collector of rare, archive designer pieces that are purchased purely for my viewing pleasure! Fashion is art. I hope the Frances O collections provide this very same joy to all who buy a piece. If someone purchases a piece with the intention of placing it on a mannequin bust on top of a marble plinth, for me, it has still served its purpose if it brings joy to the owner.

You can buy Frances O pieces at the label’s webshop, Auné, Juno Juno and Voulez Vous.