The story of America, before it was even conceived as so, begins with the land and Indigenous people. The story that America tells, though, has been violently re-written to erase Indigenous people, as well as Black people, trans people, non-European immigrants, the list goes on. Indigenous people have long fought back against this, and while The New York Times suggest that “2020 is the year to tell the real story of Thanksgiving”, Indigenous people have been telling that story all along — everyone else has simply chosen not to listen.

We are taught that the myth of Thanksgiving was first celebrated in 1621 on Wampanoag land, or in the so-called colony of Plymouth; but its first official mention wasn’t until 1637, when colonists gave “thanks” after having committed a brutal act of terrorism against a Pequot village, massacring everyone in it. The 1621 fallacy of friendly “Indians”, unidentified with tribes, peacefully conceding to the Pilgrims — thus conceding to white supremacy, settler-colonialism, Christianity and so on — exists to fatally dismiss the lives, realities and histories of Native people.

The story of this bloodless shared dinner has come to symbolise America’s brand of benign colonialism, erasing its past of genocide through massacre, disease, land theft and enslavement. It hides what Americans keep hidden about the rest of this country’s history: that thanks and celebration will always be given for the deaths of Indigenous people, as well as Black people.

Many settlers who call themselves “allies” will still celebrate Thanksgiving on stolen land during Native American Heritage Month this year. They will do this despite Covid-19 and this country’s racial reckoning. They will celebrate without regard for the Wampanoag losing their reservation status this spring; without considering other ongoing onslaughts against Indigenous peoples’ rights and lives; or indeed recognising that Thanksgiving is actually a day of mourning.

The difficulty of navigating a self-prescribed woke, performative allyship culture is nothing new for Indigenous people, especially those who live in New York City, in Lenapehoking. New York City is still Native land, the homeland of the Lenape. Manhattan used to be called “Manahatta” and a wall built by Dutch settlers — to keep the Lenape and the British out —became Wall Street. Mohawk ironworkers built Manhattan, having worked on iconic landmarks like the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, Madison Square Garden and the World Trade Center. Presently, New York City is home to the largest Indigenous population in any city across the US. Indigenous People’s Day is celebrated, even if not legally recognised, and fights to abolish Columbus Day and halt the construction of a pipeline in North Brooklyn are stronger than ever.

Just as the story of America begins with the land and Indigenous people, so does that of New York City. Yet the real Native New Yorkers, those who are Indigenous and Lenape in particular, are almost always excluded from it. Still, they carry on their ancestors’ legacy of resilience and resistance, to decolonise and indigenise. “We are still here. Lenape people and our culture are still here, intact, in Lunaapeewahkiing,” says Otaes, a Rampaough Lenape educator. “Many of our relatives were violently displaced and live in painful diaspora across both the so-called United States and so-called Canada. They are fighting to come home. The Ramapough Lenape and our relations who remain will continue to hold space on our homelands, so that all who were forced to leave can return.”

Here’s what some Native New Yorkers have to say about life, violent holidays, healing and joy as urban Natives.

Paige Cook, 21, student, writer

Tell us about where you’re from and what brought you to Lenapehoking.

I am from the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation that borders New York, Ontario and Quebec. I came to Lenapehoking for school, where I received a scholarship that allowed me to pursue a higher education at a predominantly white institute. This is something that I’ve grappled with over the years: working with and for a school that does not always support students like me, and often works against us. The more intimate question would be why I continue to choose to stay here. Each year, the city has grown around me, and I have grown into the city. In a similar way to how I feel on my reservation, the city evokes feelings of home. To know that I have family members that helped create the buildings that surround me as I walk, gives me a sense of purpose and strength when the more difficult parts of living in a settler colonial state feel suffocating. My ties to the land — my ties to the city — keep me grounded. It is comforting to imagine my mama walking the same streets I do when she’d travel to stay the weekend with her boyfriend at the time for work, to build the city I now live in. To imagine the same for so many members of my family. We are all shadows of each other, living, existing all at once in real time.

Particularly because of your own people’s contributions to the city, what have your experiences been like as a Native woman in Lenapehoking? How has navigating your identity in the city shaped or influenced it, you and your indigeneity?

I feel a sense of belonging here, in Lenapehoking, and particularly in the city. My people, Haudenosaunee Mohawks, helped build these buildings. When I walk down the streets, I am surrounded by reminiscence of the hard work that has been done to bring me where I am today. Why wouldn’t I feel connected to the creations built by my people, my family? My body often knows things before I do in that way. My genes have been created through generations of ancestral survival, and years of knowledge often shows itself through my intuition. I thank my people for all that I know.

This connection feels that much more difficult, as a Native woman in a city that consistently erases the existence of Native and Indigenous Peoples. It feels like a constant struggle between feeling at home, and feeling like someone took the keys away and is dangling them in front of you. Origin stories of the city often refer back to immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, with no caveat to the Indigenous communities that existed here before. Most origin stories refuse to acknowledge Indigenous Peoples at all. When they do, it’s painted in one of two scenarios: 1) That everyone got along and it was all merry and bright, as grade school students in the US are told about Thanksgiving. It becomes the goal to erase, paint over and rewrite the narrative to gloss over the fact that colonial states did and continue to kill Native and Indigenous peoples. 2) That settlers conquered Indigenous people fair and square because they were too weak. As if mass genocidal tendencies are something to be proud of. As if Native and Indigenous peoples do not still exist today.

Some days, I feel like I’m swimming up a waterfall at ninety degrees, trying to prove myself as an Indigenous woman. Having to teach people in my class, having to teach professors and faculty about the continued state-sanctioned abuse against Native and Indigenous communities. But some days, like every Thursday night this semester when I meet with my Native American & Indigenous Students Group over Zoom, I feel like I’m floating, head above the water, fingertip to fingertip with all the people on my team. Living in the city has allowed me to connect with my Indigeneity in different ways than I have while living on my reservation, or while living in a predominantly white area of Utah for several years. Each place I live gives me a new lens to view myself through, and this has been a chance to push myself further and in different ways than ever before. I have explored my role as a white-passing Native woman, and how my privilege functions within different spaces. Learning, connecting, and growing with Indigenous people from so many different communities has been instrumental in shaping me and my relationship with my Indigeneity.

What does Lenapehoking’s Indigenous community mean to you?

I believe the networks of Lenapehoking’s Indigenous communities serve as the backbone to the survival of Indigenous peoples in the city and surrounding areas. We are a community-driven people, who lean on each other for support and create networks of protection, love and care. We do not live in isolation. It is because of the strong networks of Native and Indigenous people that exist here that I don’t feel alone. Whenever I meet another Indigenous person in the city, it is such an exciting moment of connection and solidarity that reminds me that I’m a part of something much larger than myself. There have been moments when I’ve gone to Indigenous Film Screenings, Powwows and other events in the city where I would start out worried that I’d have no one to talk to, that somehow I wouldn’t fit in. Time after time, I’m proven wrong.

What do settlers in Lenapehoking misunderstand about Thanksgiving? About the Indigenous experience and such violent “holidays”?

Native and Indigenous peoples are constantly being erased from the narrative. If not erased, then subjugated to violent narratives that are harmful not only to generations of Native and Indigenous peoples, but to present day individuals as well. By celebrating Columbus Day and Thanksgiving, the US repeatedly tells Natives that they don’t matter. These days celebrate attempted genocide. They remind Native people that the country has tried to eradicate their existence, while working to convince non-Natives that this wasn’t as bad as it sounds, that it’s actually something to celebrate. Children are dressed up in paper feathers and hats to play Indians and Pilgrims in school, and taught that Columbus sailed the ocean blue, without a mention of the people that were killed as a result.

These types of messages impact Native children and begin to erode at their self-worth from a very young age, and this is done on purpose. This country doesn’t want to change the narrative, because the settler colonial mindset that Natives are a problem that must be eradicated still remains within the system. When I was in the third grade, during our ‘Native American Unit’, I said that I was Native, and the student across from me said that he thought all Native Americans were dead. This is the narrative that the school system pushes. This is why Native people in the US were put on reservations on lands that were considered uninhabitable. It is why Native children were sent to residential schools. It is why pipelines are built through ancestral lands, and toxic waste is dumped into water supplies. The US, as an institution, wants to erase Native people by any means necessary. Celebrating these holidays, especially without the recognition of the damage it causes, reinforces these goals.

What do healing and self-care look like for you?

This year in particular, I have tried to put a huge focus on taking care of myself and leaning into any pockets of joy I can find. I try to do at least one nice thing for myself per day. So many things in the world aren’t being kind to us, so we should at least be kind to ourselves. We need to be on our own team. I try to practice forgiveness and give myself breaks, something I couldn’t even imagine thinking I was allowed to do a few years ago. I talk to my ma more, and my younger brothers and cousins. All of the loves and lights of my life. I find it so important to stay connected to my family, and I’ve learned that keeping that connection up while I’m away is instrumental in my healing process. I’ve learned how to bead in the last few years, which helps me feel more connected to my community while I’m away. I’ve finally started therapy, which I love, and am very proud of myself for finally making that jump. I try to remind myself of all the things I should be proud of! I let myself feel happy when it comes, and keep searching for new ways to channel that joy. I love extra hard. I love, and I love, and I love.

How can settlers in Lenapehoking best celebrate your community?

Buy from Indigenous artists, hire Indigenous creatives, support Indigenous workers. My community and countless other Native and Indigenous communities have talented beaders, dancers, painters, actors, scientists and so much more. Pay them.

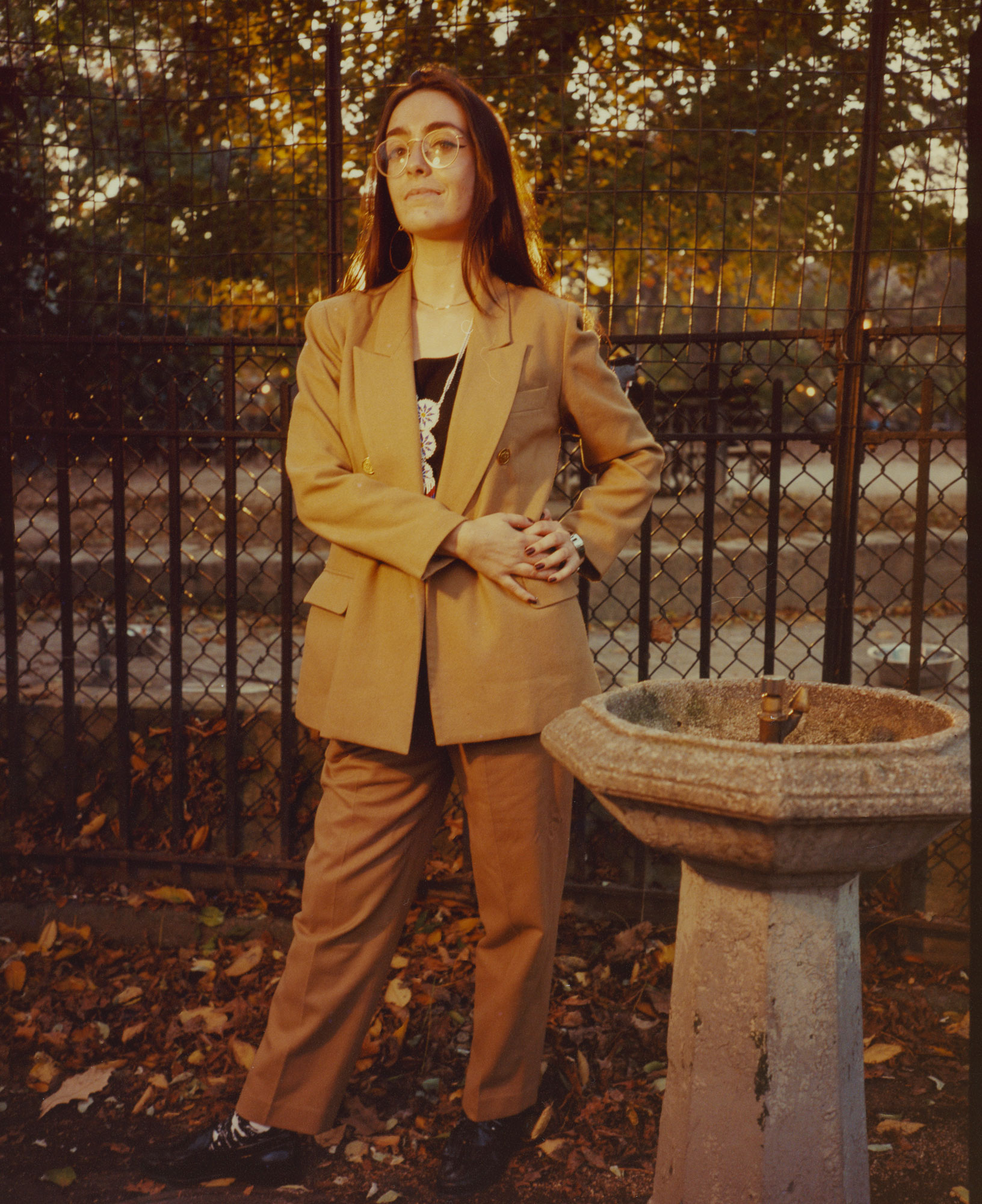

Sequoia, model

Tell us about where you’re from and what brought you to Lenapehoking.

I am originally from Virginia and as a model and creative, Lenapehoking is fertile ground.

What have your experiences been like as an Afro-Indigenous person in Lenapehoking?

Being a creative in the city allows me to embrace every part of who I am. Especially with the tight knit Native community and abundant Black community in Lenapehoking, everything I already am is not only encouraged, but embraced. I am “ethnically ambiguous”, so I often have my ethnicity wrongfully assumed by others because of the erasure of Indigenous people. I am proud to be both Native and Black. I am the result of the shared bond between America’s most oppressed, overlooked and undervalued peoples. I am the result of that shared resilience, beauty and depth of love that allows us to carry on forward, despite our open wounds.

What does Lenapehoking’s Indigenous community, and community in general, mean to you?

Lenapehoking provides a myriad of Natives from all over with distinct cultures, personalities, talents and stories, yet collectively we have an unapologetic ardor that fuels our commitment to the next generations and pays respects to the generations passed. Community based on mutual understanding, respect, love and dedication is important. Community is how we continue.

What do settlers in Lenapehoking misunderstand about Thanksgiving? About the Indigenous experience and such violent “holidays”?

They misunderstand the real story of Thanksgiving, just like they misunderstand the real story of how America came to be. They misunderstand, rather, ignore that we are still here and still experiencing erasure. For example, we are talked about in a pitiful past tense and yet, I am here talking to you and I am not pitiful at all.

What does healing look like for you? What role does joy play in your life?

I carry joy with me always, even on my worst days. I just remind myself of all the blessings that surround me and that reconnects me to my joy. I heal by being in my own space — that’s extremely joyful.

How can settlers in Lenapehoking best celebrate your community?

Do your research on the true story about the land you are living on. Expect uncomfortable truths and accept them. Understand that we are still here and respect us as people in the present time. Don’t assume our cultures, be open to respectfully learning. Then, we can “celebrate” as a community, because the door to mutual respect has been opened.

Keep decolonising your mind.

Shea Vassar, 26, writer, film critic, wearer of many hats

Tell us about where you’re from and what brought you to Lenapehoking.

I am originally from so-called Oklahoma, which is former Indian Territory that many Native nations call home after being forced to. I spent some time in the northern part of so-called Florida on Mvskoke homelands before making my way to Lenapehoking. My original goal was to be a comic, but I am not a night person and no one wants to hear self-deprecating jokes at 8am. So, I got into writing about new film releases.

What have your experiences been like as a Native woman in Lenapehoking? How has navigating your identity in the city shaped or influenced your indigeneity?

Most people see New York City as a left-leaning metropolis, when the reality is, there are everyday microaggressions that have stuck with me as a Native person. And there are times that connecting with my indigeneity is more difficult because there isn’t the direct connection to water and hiking. I grew up in what most would consider ‘nowhere’ and spent my days outside climbing trees all summer and sledding all winter. But a recent revelation changed my perspective on my urban connection to the Earth: land doesn’t go anywhere, and despite there being buildings and streets over this Native land, it is still there.

This concept of Urban Land is parallel to the existence of Urban Natives: we are here. There are other ways I’ve started to explore my indigeneity, like growing 16 corn plants on my stoop this past season. My harvest wasn’t great, but it really was special. I spent many mornings sitting with my “selu babies” — selu is corn in Cherokee — and would bring them inside during heavy summer thunderstorms. This was just my first time, so I learned a lot and can’t wait to plant and watch them grow again! Of course, there is still the fact that I am a Cherokee woman occupying someone else’s unceded land. This is not my land, but I will fight to protect it against the trauma of police brutality or the non-consensual North Brooklyn Pipeline.

What does Lenapehoking’s Indigenous community, and community in general, mean to you?

Without hope, we have nothing. But without community, we have no one to share that hope with. Capitalism has encouraged us all to become so selfish, focusing on how we can be richer or more successful in the worst sense of that word. True community that is built on unconditional love values everyone for what they have, rather than cutting anyone down for what they lack. We all have skills and talents and community embraces what each and every individual is good at.

The concept of true community is still a fairly new thing, especially in the Native sense of the word. My move to Lenapehoking was really the catalyst for me to reconnect with my nation. Through this, I also found more of the diverse Indigenous community that exists here in an urban setting and I continue to meet more Native people — mostly virtually these days — in my immediate vicinity.

What do settlers in Lenapehoking misunderstand about Thanksgiving? About the Indigenous experience and such violent “holidays”?

These all are a form of erasure and continued genocide. We are at a place where everyone should be open to questioning the origin of all of the traditions, holidays and historical stories — that are really propaganda — and be allowed to make informed decisions whether or not we create a better, safer future for the upcoming generations. There is still so much work to be done and the majority of that labour falls on Black and Indigenous people, which is the opposite of what the liberal movement would like everyone to believe.

What do healing and self-care look like for you? What role does joy play in your life?

Healing is not a linear process. It is complex, unpredictable and different for everyone. I’ve found that as I search for healing for both me and my family in different areas, I discover more of the inner paradoxes of being human that cannot fully be explained through words. There is something beautiful about how messy we all are, collectively and individually, and I’m learning it’s better to embrace that than act like those quirks don’t exist.

As for joy, Regan de Loggans once said something that really stuck with me. They said: “Joy is such a radical thing for people that were not even supposed to survive.” That really stuck with me because all of the hardships that not just my ancestors endured, but the many hurdles colonisation has set up for many different communities to jump over. We aren’t supposed to exist, yet we do. This simple fact is enough for me to just sit and really be grateful for another day. Sure, sometimes I wake up and I see the world around me in shambles and just want to go back to sleep until this entire mess is cleaned up, but that’s not going to happen unless we make it happen. That’s where self-care comes in. I’m a perfectionist, so sometimes I get angry at myself for not sticking to a “self-care routine” — I’m a Virgo sun. I’m learning self-care can be as simple as a good cup of tea before bed or putting my phone away to read a favourite poem.

How can settlers in Lenapehoking best celebrate your community?

Listen to Indigenous people and their movements. We are not a monolithic group and so many talented and powerful people from all different backgrounds and experiences make up the Native community here in occupied Lenapehoking. We are all expressing ourselves and being open about our pasts and our futures. The best way to celebrate our existence is to listen to what we say and uplift our work regarding advocacy, supplementary education, creative output or just us being the Native hotties that we are.

Xandra Hafermann, 22, actress and creative

Tell us about where you’re from and what brought you to Lenapehoking.

I grew up on unceded Coast Salish territory on the Canadian side of the border, in a predominantly white and East Asian city. New York has always felt like a second home to me, so I knew I’d eventually return to the place that most understood my multiple heritages.

What have your experiences been like as an urban Native? And more specifically, as an Afro-Indigenous and trans woman in Lenapehoking?

Growing up, I was surrounded by people of different Indigenous backgrounds at a young age — Musqueam, Skwxwú7mesh, Cree, Métis — and my Native friends always accepted me as their own, even though I wasn’t raised by my Indigenous side of the family. However, I’ve always felt somewhat misunderstood. Since moving to New York, I’ve experienced some of the most difficult times of my life, but also the most special.

I often find that I pass as cisgender and as white or ethnically ambiguous. Being of mixed heritages sometimes feels like I’m in between worlds, but this also gives me a great latitude between communities. And as a trans woman, I love living in a city with so many brilliant queer people of colour.

What do settlers in Lenapehoking misunderstand about Thanksgiving? About the Indigenous experience and such violent “holidays”?

Thanksgiving is celebration of genocide. The Northeast is riddled with statues of our colonisers and enslavers, and every time we walk past these statues, we are reminded that the world still views us as “the conquered race” or “the extinct Indians,” and that’s shameful because we are very much living and present in your cities.

Now is the time that we need our “woke” white friends to listen. Talk to your families, give them a history lesson on the origins of Thanksgiving. Educate yourself on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls throughout the US and Canada. Follow @missing.murdered.natives, watch Highway of Tears and Finding Dawn and read up on the environmental destruction that the 2010 Olympics caused to the Tsleil-Waututh, Lil’wat, Skwxwú7mesh and Musqueam land and ecosystems.

Many Americans know about Standing Rock’s protests in 2016 and 2017. Now educate yourself on Wet’suwet’en and land defence protests everywhere — the struggle for Indigenous rights goes beyond America.

What do healing look like for you? What role does joy play in your life?

Connecting to my cultures and learning more about my people’s history and traditions is a form of healing for me. The earrings I’m wearing are made by my mother, who beaded them in colours of the Yaqui flag. She runs a shop, @mybeadedhart on Instagram. The necklace I’m wearing was made by Yaqui organiser Carlos Valencia of @yaquipride. The pendant is called Ojo de Venato, or Maso Puusim in Yaqui, which translates to Deer’s Eye, and it protects me from negative energies. I’ve been learning a lot about Yaqui culture on both sides of the border, as it cuts our nation in half, from Carlos and relatives that I’m growing closer to. It’s a balm for me, after growing up in such a white community.

As a queer person, I have to remind myself quite often that we are on a different timeline than our cishet counterparts. For me, self-care is forgiveness. Humour is also essential in my life and that humour connects us to each other through identification. Humour is the way we make it together through difficult times. My queer and BIPOC friends understand when I say that humour is necessary for healing in our communities.

How can settlers in Lenapehoking best celebrate your communities

Education is the best form of celebration — readings are open to everyone from any walk of life. If you want to learn more about my cultures I recommend Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria Anzaldúa, Miscegenation Blues: Voice of Mixed Race Women by Carol Camper and Whipping Girl by Julia Serano.

Diannah Reid, 27, artist, painter, mother

Tell us a bit about where you’re from and what brought you to Lenapehoking.

First of all, yá’át’ééh! Shik’èí dóó shidine’è, Shí’ eí, Diannah yinshé. I am a Diné [Navajo] woman from Northern Arizona, and that was a greeting in Diné. I am of the Áshiihíí (Salt People) and Born of the Todích’íí’nii (Bitterwater People). I am a mother, a painter, artist and an assistant manager for an insurance brokerage. I have lived here on Lenapehoking for the last 8 years. I came to this land, not knowing what life will bring me, after the passing of my father. Being here, it was a culture shock, especially for a young Diné woman.

Once I began working as an independent artist and painter, I researched local Indigenous events and discovered that there were others like me living here — whether it be for schooling, working or leaving the reservation. It felt good to know that I wasn’t the only “Native”.

At the beginning of the year, I began to learn more about Diné culture. Calling my nálí lady (grandmother) and chit-chatting about stories and songs, listening to other Diné folks. Upon further reading and listening, I noticed the culture has begun to diminish and only a handful of people still do traditional things. A lot of people within the Diné culture don’t want us to be traditional anymore. That is where I come in, reteaching cultural subjects that some individuals forgot. Of course, when one person in the community tries to teach the culture, a lot of people are uncomfortable with the subject. That is when I have to put my foot down and tell them that the culture is being lost and that if no one is going to do it, who will?

I was raised knowing that culture is vital, especially when people don’t want the culture to flourish. Doing these things with the little ones also strengthens our bond and passes on the ability to continue doing these teachings. So, you can say I do teach anyone who wants to learn. I also started to do commission-based work and slowly made time to have my creative side flourish yet again.

What have your experiences been like as an urban Native, especially as a Native woman in Lenapehoking? How has navigating your identity in the city shaped or influenced it, you, and your indigeneity?

I suppose I never considered myself an “urban Native”. I would say that I am known in my community as a black sheep. My intention in leaving the reservation was to show people in the community that it is possible to do things on your own, especially to the younger community. Leaving the reservation was the best decision for me at the time. Moving to a far away, more urbanised land, and being on Lenapehoking, as a young, Indigenous Diné woman started to affect me mentally, emotionally and spiritually. Living far away from family and my loved ones, I had to cope, but they all remind me everyday that they are here with me, no matter the distance.

I was raised with traditional teachings. Thankfully, shí nálí lady (paternal grandmother) is still here teaching me songs, prayers, medicine, stories and language. My eldest brothers, my mother, my aunties, my uncles and my friends still call me and keep in contact with me. I am very happy to have come from a strong and resilient background. I am very fortunate to be able to speak Diné Bizaad, my native language. Most Diné individuals that I have met here don’t speak much of the language anymore; I realised that our language was disappearing. As the Covid-19 situation arose earlier this year, I began to teach the basics like numbers, clans and kinship relationship systems. Residing in Lenapehoking has helped me educate myself, so I deal with neighbours and my non-Indigenous friends to teach them that us Indigenous folks are still here.

Has Lenapehoking influenced your creative direction as an artist?

Honestly, Lenapehoking has given me the opportunity to educate myself. I reside on Lenape land, thus I have to be respectful. My creative output as a freelance artist and painter has given me the ability to do my artwork on this land. I have to respect it first, offer my tobacco and corn pollen to give thanks. Then in return, the land will give me positive energy.

What do settlers in Lenapehoking misunderstand about Thanksgiving? About the Indigenous experience and such violent “holidays”?

Within the past few years, a group of protestors and Indigenous communities have rallied to protest for removal of the Columbus statue, as well as the statue of Teddy Roosevelt in front of the Natural History Museum. Us Indigenous folks are still here to protest and to remind others that this was originally our land. As much as we try to teach people about the real “Thanksgiving” and “Columbus Day’’, not a lot of people want to learn. We should preach this more and we need politicians, schools, and Lenapehoking settlers to do more. To acknowledge the real facts. It’s 2020, people!

What do healing and self-care look like for you? What role does joy play in your life?

As far as healing and self-care, to me it’s about doing things that bring me peace. Painting gives me a sense of freedom. Beading also is a source of mind healing. Praying to the morning star with my corn pollen. It’s the little things that I remember doing with my father, and my nálí. It brings a sense of stability and remembrance of being a Diné woman. As for re-teaching the basic fundamentals of Diné Bizaad, it has given me so much joy to keep the roots going and that teaching these teachings can be passed down, no matter the circumstances.

How can settlers in Lenapehoking best celebrate your community?

To support the Indigenous community, donate and help out in protesting; acknowledge the Native land you are on; and listen. Respect the people who are here now and who were here originally.