Russian artist Yulia Tsvetkova is facing up to six years in prison. Her offence? Creating a series of drawings of the nude female body, which she then posted online. Ridiculous as the grounds for her prosecution may seem, hers is but one of the many politically-motivated cases against young people in Russia today. What makes Yulia’s situation particularly noteworthy, though, are its potentially significant implications for the country’s feminist, LGBTQ+ and creative communities, exposing the Russian government’s hostility towards women and queer people. But it also represents a far more global issue: the censorship of the female body, an issue which affects women both online and offline, wherever they are in the world.

27-year-old Yulia is from Komsomolsk-on-Amur, a city of 250,000 people in Russia’s Far East. From a very young age, she showed an interest in art and creativity, eventually taking on a role as the director at a youth theatre, running several online groups focused on feminism and youth sex education at the same time. It wasn’t until March 2019, however, that the authorities began to take an interest in her work, when the police started investigating The Blue and The Pink, a children’s play Yulia was producing that explored gender stereotypes. For this, she was accused of spreading “homosexual propaganda” to minors and was later fined. On 20 November 2019, she was eventually arrested and placed under house arrest, this time charged with the “production and dissemination of pornographic materials” on her social media channels.

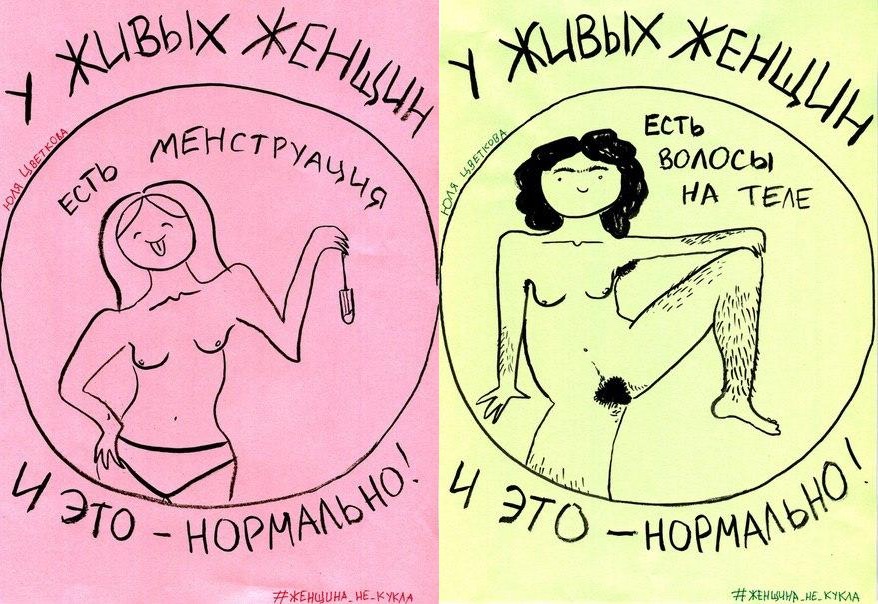

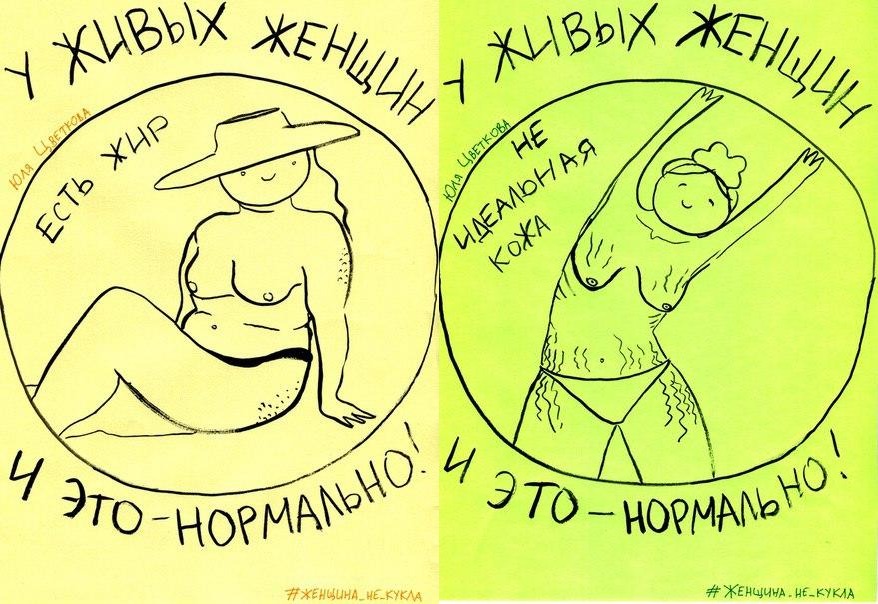

At the beginning of this June, prosecutors confirmed that Tsvetkova was still due to stand trial for distributing said “pornographic materials” — cartoonish drawings of women with captions that read: “Real women have body fat — and it’s normal” and “Real women have wrinkles and grey hair — and it’s normal”. The news has caused outrage among Russia’s feminist and creative communities, sparking a series of protests across the country — all of them single pickets, in compliance with local social distancing guidelines, as well as with Russia’s harsh laws dissuading public protest. These demonstrations were organised and coordinated by feminist activists Lolja Nordic, Dasha Serenko and other feminist activists, who also held a wide-scale online solidarity strike across media platforms on 27 June.

“Yulia Tsvetkova is being persecuted for her feminist views and LGBTQ+ activism — her case is an expression of the homophobia, misogyny and sexism of our state,” says Lolja, a feminist and eco-activist, artist and DJ. “If Yulia goes to prison, it means that any other artist or feminist activist could be incarcerated at any moment. Fighting for Yulia’s freedom means fighting for everyone’s freedom, as well as against fabricated cases and political prosecution.”

As Lolja points out, Yulia’s case underscores the powerlessness that Russian women experience when dealing with the country’s judicial system. Perhaps the most alarming example of this is the absence of laws that actively protect women from domestic violence — in fact, it’s essentially decriminalised. Instead, the task of caring for domestic violence survivors inevitably falls to grassroots activists like Lolja, who is a co-organiser of NE VINOVATA (“Not Her Fault”), a DIY charity festival, that offers support to women in 40 cities across Russia, Georgia and Poland, providing the support structures that governments neglect to.

As is likely evident from the above, feminism is a dirty word in Russia — one which, in the eyes of the establishment, threatens ‘traditional family values’. Through her work, this perception of feminism is something that Yulia, and the growing community of activists she’s part of, have been trying to change. Much of this creative, artistic and social activism has typically taken place online, and it’s where women across Russia took to in order to show solidarity with Yulia, posting nudes on Instagram under the slogan: “My body is not pornography”. These expressions of feminist body positivity were, however, swiftly shut down: within a few days, corresponding hashtags were completely hidden, with many participants shadowbanned.

In response, London-based Russian photographer Emmie America, who felt incredibly impassioned by Yulia’s case, started a project which could help raise awareness on social media, while swerving its prudish restrictions. She offered to take ‘Instagram-safe’ nude photographs of anyone who was willing to spread the word, concealing nipples and pubes — which are cause for censorship on the platform — through poses and movements. The resulting images, while of nude bodies, are also non-sexualised: they’re simply pictures of the bodies we live in.

“It’s been a really interesting and emotional experience shooting nudes of people, most of whom I have never met”, says Emmie. “It made me think about women’s relationships with their bodies, self-image and self-esteem, and the power we have as photographers to shape notions of beauty. We need to use this power to make a positive change rather than keep up oppressive restrictions”.

“For all the people connected to feminism, LGBTQ+ or activism in Russia, the message communicated via Yulia’s case is: ‘Stay silent or you’ll be next’”, says Miliyollie, a Russian photographer and body positivity activist. “It is actually scary that you could be imprisoned simply because certain people with power don’t like your art. In Russia, we’re seeing more and more politically-motivated cases. But I hope we manage to win the fight for Yulia’s freedom — people’s attention and anger can still have an effect.”

Miliyollie admits that, as a fat queer person with a disability who focuses on diverse bodies in her work, she constantly feels pressured, silenced and confronted with hostility on social media and in other online spaces. And that’s not just down to the state-sanctioned oppression of body positive creative expression specific to Russia — it’s also due to the lack of diversity in visual culture worldwide.

“Why is it that a skinny white body, especially if it was drawn or photographed by a white cis-man, has more of a right to representation than the bodies of fat people, people of colour and trans people? Why are the images of the former in the museums, while the latter get blocked on social media as inappropriate content?” she asks.

Sasha Kazatseva, a queer sexual educator and co-founder of O-zine, a publication about Russian queer culture, echoes Miliyollie’s frustrations: “I find it really paradoxical that in 2020, when we respect science and medicine so much, a person’s body — particularly what we call a ‘female body’ — is still considered socially inappropriate and indecent. I find it paradoxical that there’s a division between a ‘male chest’, which is permissible and normal, and a ‘female chest’ which is impermissible and vulgar,” she says. “Yulia’s case is unbelievable — there are students in art schools who draw far more ‘realistic’ nude images. It says a lot about how Russian governmental institutions treat people as well as about their support for queerphobic discourse”.

The importance of Yulia Tsvetkova’s case for Russia’s youth can’t be understated. It’s not just a fight for one person’s freedom — it’s a fight for freedom of expression, women’s rights and LGBTQ+ equality for all; it is a fight for free access to safe spaces and educational resources online; it is a fight for the right to be outspoken and free — on the streets as well as on social media. With the Russian constitutional referendum that’s taking place today (1 July), which would allow Vladimir Putin to stay in power until at least 2036, this fight is likely to become even more challenging. Still, Russia’s youth must not be deterred.

“The government is arresting activist youth to freak us out, to scare us off,” Emmie America sums up. “In moments like this, the most powerful thing we can do is unite and stand together.”

Sign the petition for Yulia Tsvetkova’s freedom here.