As you enter the new Tate Modern building, Switch House, you are greeted by the writhing performers who enact artists Alexandra Pirici and Manuel Pelmus’ new work. Slipping around one of the new gallery spaces devoted to performance art, they reenact art works from the museum’s collection as performance pieces. It is hard to place exactly which ones at times, as they range from the famous to infamous, from the seminal to the unknown, from Carl Andre to Mark Rothko, from Tania Bruguera to Doris Salcedo. When I enter, one of the performers is squatting, hips thrust forward, legs splayed. A woman standing near by is shouting loudly about vaginas and orgasms. It could be a scene from a satire on modern art, but it is, suggestively, a satire of modern art, as well as celebration of it. What better way to ring in the new building?

That we are now comfortable enough with contemporary art for the country’s biggest contemporary art museum to literally build its new home upon such experimental and metatextual art practices (the performance spaces are on the bottom floor of the new building) is indicative of the way contemporary art has changed and grown in the 16 years since the Tate Modern first opened its doors. The first thing you encounter here, if you slip down the ramp of the Turbine Hall, is not some grand gesture that the museum is so famous for — no carpet of Ai Weiwei sunflower seeds, no giant fissure cracked down the concrete floor, no looming suns, no sweeping and swooshing Anish Kapoor monolith. Instead, here are the temporal, ephemeral, art practices that should be supported by museums and institutions — practices that aren’t easily commercial, practices that are easily lost in the bluster and bravado of modern art.

When Tate Modern opened no one expected it to be such a huge success. They expected two million visitors a year (max); they now regularly get over five million. This extension — which increases the museum’s size by 60% — recrafts the Tate for 21st century. The extension recalibrates the institution for the art industry that has sprung up in its wake, an industry whose tentacles slip into the provinces — not just in Tate Liverpool and St Ives — but in The Baltic in Gateshead, the CCA in Derry, MIMA in Middlesborough, FACT in Liverpool, The Turner Contemporary in Margate, Nottingham Contemporary, Wysing in Oxford.

By this measure alone, the Tate has, undeniably, been successful in its mission to bring art to Britain, or at least to update its art culture. Before the Tate Modern there was no dedicated public museum for modern art. But the Tate Modern has made modern art part of the national consciousness. It rode the controversies of the YBAs and moved art forwards; it turned art into a vital part of our post-industrial industry — one of the few things we still make here these days (something that Brexit would almost certainly kill off).

When it first opened, the Tate was a bastion of the Western art narrative: a predominantly male, predominantly Modernist (or variation of) canon of 20th century — of New York and London, Paris, and Vienna. Switch House and the rehung old galleries, though, tell a wider, more expansive story that takes in east and west, Chile, Brazil, Russia, Africa; there are 800 works by 300 artists from 50 countries. 50% of the work in Switch House is by women. The Tate Modern — with its thematic, rather than chronological, rooms —proposed a new approach to art curation. The new displays build on this; they’re filled out with newly acquired works, 75% of which have been acquired since 2000.

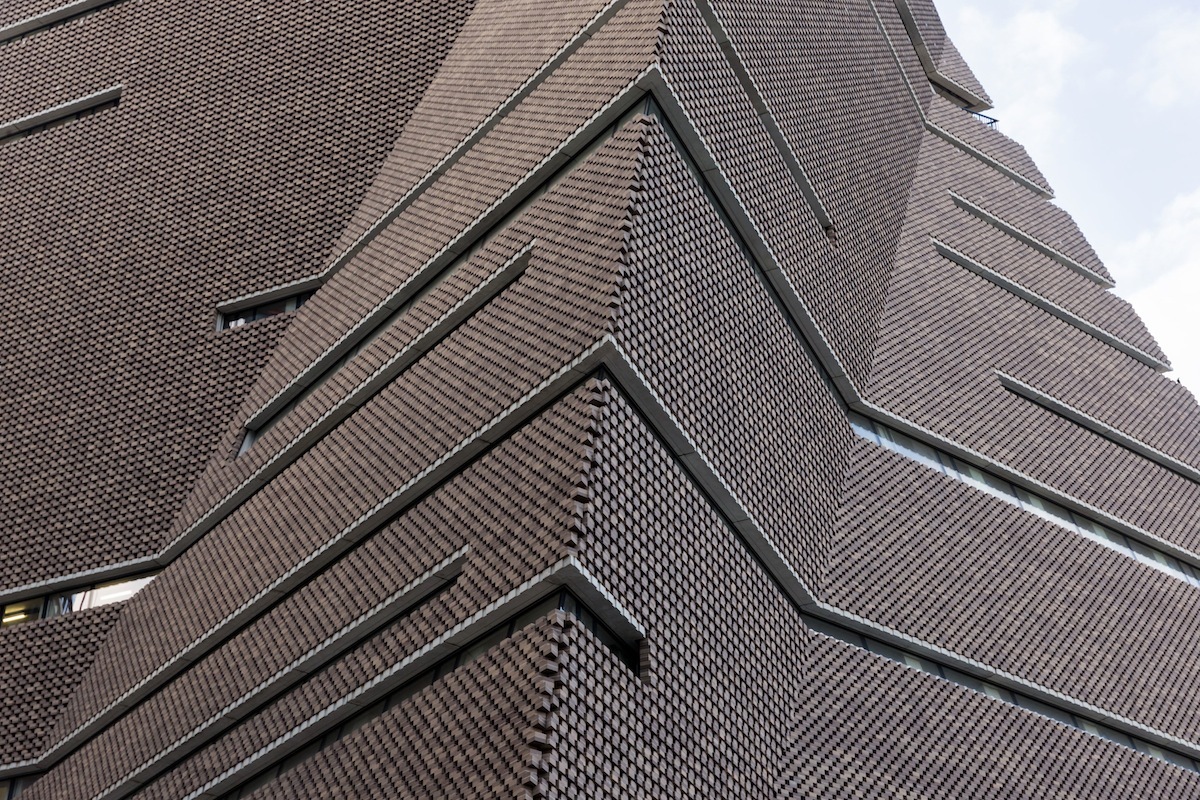

Switch House is what’s really interesting, though, and what is going to get all the attention. Firstly, the building itself: it boasts a subtly monumental quality — its brick concertina folds into and out of the landscape, and lurks behind the old power station as you approach from across the river. Up close it’s riveting: a slightly off, slight askew, double of the power station chimney. Inside, past the performance art and up a spiraling staircase you’ll find three floors dedicated to art post-60s, art after post-modernism, and art’s changing relationship with audience, with itself, with the gallery. There’s also a spectacular 10th floor viewing platform — which the old chimney dominates, like a church spire — just adjacent to the older, more sacred dome of St Paul’s. You can’t help but draw parallels between the two; one was once the center of the city, the other, arguably, is now. Sadiq Khan, the newly elected mayor of London, certainly thinks so. Speaking at the opening on Tuesday, he expounded on the place of culture, arts, and creativity in the city, and how his London needs to supports its artists and create spaces for them. He explicitly spoke on making them affordable.

The art itself in Switch House is stuffed full of treasures, unexpected treats, which often slip from the obvious into more subtle, contemplative territories. There are some blockbuster pieces; Helio Oiticia’s Tropicalia — an immersive installation of real live macaws in a cage, sand strewn gallery floors, and twisting labyrinthine boxes — is sure to become an instant favorite.

The themes of the floors, Living Cities, Performer and Participant, and Between Object and Architecture, plot out the developments in the gallery’s collection in the last 16 years: performance art, photography, female artists, modern conceptual works, interactive pieces, video works, pieces from around the globe.

There are some other instant highlights in the collection here for the viewer, though not all the work is obviously instantly gripping. Carl Andre’s Bricks have lost their shock value, and so, their aura. Roni Horn’s Four Tons, four tons of pink glass, is beautiful and perplexing, next to the window, trapping light, slowing it down, bending it. Hot on the heels of an incredible revue of his work at Hauser & Wirth, Felix Gonzalez-Torres is represented with a stack of posters you are free to pluck from. Two touching, symmetrical gold circles form a symbol of gay love, a theme throughout the artist’s work. The whole of Level 2, in fact, where these works sit, feels like a masterful stroke of curation — a big long space stuffed full of some of the most powerful works of the recent past.

Louise Bourgeois’ artists rooms presentation is (bar the Helio Oiticia) the other stand out. A collection of her later works, some Cell works, a male body hung from the belly button, a mobile of clothes, a room of small sculptures, series of monumental drawings, and her last vitrine, made in 2010, before her death. It feels a neat bookend for Tate Phase Two, as Louise’s spider famously crowned the original gallery’s opening 16 years ago.

Credits

Text Felix Petty