As I sit down to write this piece, the 24th English Premier League season has kicked off with all the slick predictability of a business worth £5.1bn in TV rights. On the opening weekend there’s already the excruciating deja vu of an Arsenal capitulation; the first of what will surely be several hundred Mourinho meltdowns; and, of course, the one thing you can count on more than any in modern football: the continuing absence of an openly gay player in the league.

There are currently more 5,000 male professional footballers in Britain and yet not one of them is publicly gay. Stonewall did the odds on this and the chances of it being true – of there being no gay person in a random sample of 5,000 – is a mind-boggling quadragintillion-to-one (or the equivalent of predicting 150 football matches in a row). So what gives?

How is it possible that twenty-five years since Justin Fashanu became the first openly gay man to play in the UK (and almost eighteen years since his suicide lent a tragic sense of finality to him being the last), British football remains a place where homosexuality must be kept hidden – both on the pitch and in the terraces?

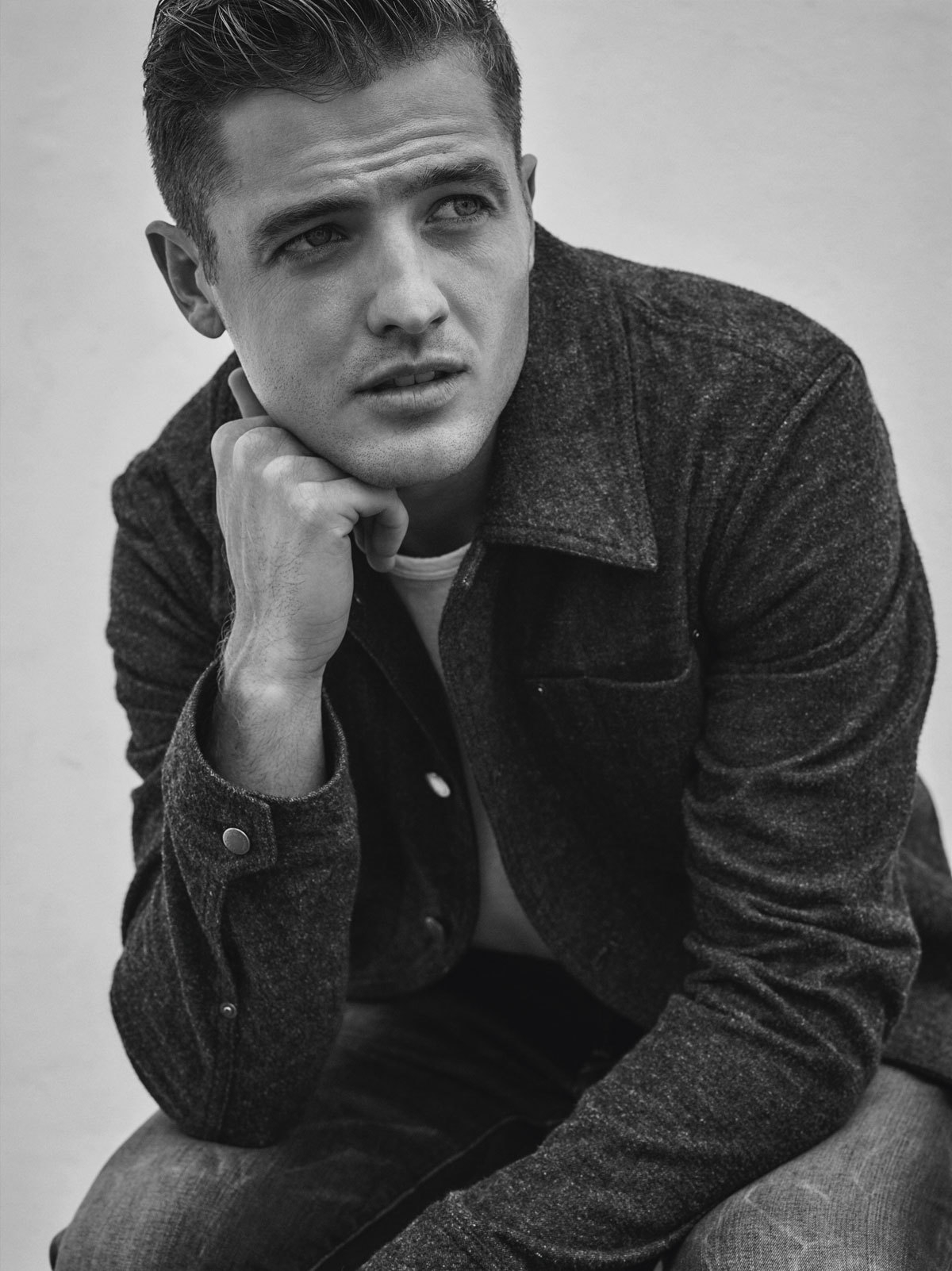

For former Leeds United winger Robbie Rogers, it’s the sport’s longstanding history in Britain – and all the traditionally male, working class ideals that come with it – which creates a sense of taboo. “There’s a stereotype of what a footballer should be in the UK,” he says. “And it isn’t gay.”

Back in 2008, Rogers was described as “the most dangerous American left-side player” of the season. He was the rising star named MLS Player of the Week; the promising, young athlete representing his country at the Olympic Games in Beijing; the blonde-haired kid from a close-knit conservative family that embodied red, white and blue suburban America better than anyone. What’s more, he was secretly gay.

“For the past 25 years I have been afraid,” wrote Rogers in the 408-word blog post that announced both his sexuality and retirement from the game in May 2013. “Afraid to show whom I really was because of fear. Fear that judgment and rejection would hold me back from my dreams and aspirations. Fear that my loved ones would be farthest from me if they knew my secret. Fear that my secret would get in the way of my dreams.”

Fast forward two years and Rogers is happily back playing again, coming out of retirement to sign with MLS champions LA Galaxy and becoming the first openly gay man to compete in a top North American sports league in the process. But it wasn’t easy.

“Although I think this is changing, I felt a pressure to live up to this ‘straight, masculine athlete stereotype’,” he says. “The locker room is like no place on earth. It’s a place where a lot of banter is thrown around, where men act as kids, where athletes prepare for battle. Before I came out, I heard the most ridiculous homophobic things being said there. What was said in locker rooms over the years made me think that a gay athlete couldn’t exist.”

Since coming out, however, Rogers has noticed a change among his fellow players. “The same guys that said things like, ‘being gay disgusts me’ are the same ones that have showed me so much love and support. It made me really realise how people could get caught up in banter and that athlete pack mentality.”

It’s this pack mentality that seems to be at the heart of homophobia within the game. From players adopting traditionally macho mindsets in order to fit in, to supporters colluding with and fuelling homophobic banter in an attempt to intimidate opposition players, we witness a contradiction whereby the same people that detest homophobia in day to day life, will engage in homophobic ‘banter’ through fear of being seen as different at the football.

For leading gay rights campaigner Peter Tatchell, this use of homophobia is ironic due to the game’s history as a traditionally homosocial sport. “You’ve got all male teams and predominantly male fans. When players score a goal, they hug and sometimes even kiss each other. They’re running around the field in short shorts and showering naked together after the game.

“Looking at football objectively, there’s a streak of homosociality and homoeroticism running right through it,” he says.

Tatchell recounts a story where one player told him that a footballer’s locker room is like a gay sauna without the cruising or sex, in which teammates will “rub each other down and put on ostentatious displays on nakedness.” And while this streak of homoeroticism isn’t always so explicit, Tatchell believes that, for some people, homophobic banter has become a kind of coping mechanism.

“At some level, fans and players recognise that they’re on the border line of something that could be construed as homosexual, so they use homophobia as a way of distancing themselves and asserting their heterosexuality,” he suggests.

Regardless of its origins, homophobic banter is prevalent in the stands in a way that other forms of bigotry no longer are. Despite the presence of two openly gay players in the current England women’s squad, attitudes within the male sport continue to lag behind in a way most comparable to the racist conditions British football combated in the 1980s.

“People talk about homophobic banter,” says Dave Raval, media coordinator of Arsenal FC’s LGBT supporters group, Gay Gooners, “but there’s no such thing as ‘racist banter’ anymore. That doesn’t exist. It’s not allowed. And the reason we’ve largely tackled racism is, actually, if you were racist in the stands, most of the supporters around you would go: ‘what the hell’s this?’. They wouldn’t accept it.”

Formed in February 2013, Gay Gooners was the UK’s first LGBT footballer supporters group, one that now maintains the full backing of Arsenal FC itself. “The club put up a big banner in the stadium which is displayed every home match – a big rainbow banner saying ‘Gay Gooners’. We do various events with the club, on and off the pitch. We were the first club ever to go to London Pride and have representatives of the club there. And we’ve grown now to about 400 members, 40% of which are women, some of which are trans, and I think that makes us, definitely in England, the biggest LGBT fan group there is. All in two years.”

The growing visibility of Gay Gooners is a definite step in the right direction, as is formation of the several other LGBT supporters groups that have since sprung up around the country, such as LFC LGBT (Liverpool), Canal Street Blues (Manchester City) and Proud Canaries (Norwich City). Yet, with so many such groups now existence, why isn’t the support shown in the stands translating into an openly gay player on pitch?

“We’re definitely moving closer, but there’s still a big fear factor,” explains Tatchell. “Players are fearful of negative reactions from teammates and fans. My view is that those fears are exaggerated.”

Tatchell points to a study of over 3,000 fans and footballers by Staffordshire University, which found that 91% felt that only a player’s performance mattered, while just 9% had a problem with their sexuality.

“It shows that the fear of fans reactions is much greater than the reality. I’m certain The PFA (Professional Footballers’ Association) are aware of quite a few gay or bisexual players but the feedback I’ve heard is that they’re all afraid to come out because they feel that they’ll be subjected to intrusive, media attention and targeted by fans. My suspicion though is they’d actually get huge praise from the media and the public, just as the Welsh rugby player, Gareth Thomas, received when he came out.”

Simone Pound has been Head of Equality and Diversity at The PFA for the decade. A former i-D alumni – recruited to work on the front desk by Tricia Jones in 1993, no less – she has spent the last few years working towards creating an inclusive environment within the sport, one in which any player, manager or coach who is gay will feel comfortable enough to come out.

“In terms of the football industry, it is a very male culture,” she says. “In the main, the players are coached by men. They go into a club from as young as seven and stay within that till they’re released from the game. It’s a very closeted and very male environment. A lot of the work that we’re doing is trying to look at the culture of the game and how we can change that very traditional mindset to become a lot more inclusive and celebratory of diversity.”

For the most part, that means equality and diversity training programmes for first team players across the Premier League and Championship, as well as supporting The FA during their work with the Gay Football Supporters Network (GFSN) and a fledgling group called Pride in Football, both umbrella networks for LGBT specific fans groups such as the Gay Gooners.

“I think it’s really key that big clubs recognise their gay supporters,” says Pound. “To get them included within the club and ensure that the club recognise them and that they’re as much a part of it as any supporter. We’re seeing that a lot more, but I still think more can be done.

“To have to run out in front of 50,000 people who will be supporting you one minute, but if you miss or flunk something will vilify, not just you, but sometimes your partner, your family, your children. I can understand why, potentially, a player wouldn’t want to put himself out for any additionally abuse. You can’t put that on one person.”

What then, about the possibility of the PFA encouraging several players to come out jointly, at the same time? That way no individual player would be the focus of attention, it would give them security in numbers and might even make it easier for them to agree to come out.

“We’re a trade union so I’m a strong believer in the power of numbers and people supporting people,” explains Pound. “I hear what you’re saying, but I also think that as well as having people that are gay and comfortable coming out publicly as gay, it’s about having straight allies and having straight men saying that they’re supportive of and comfortable with their gay colleagues. It’s having that mentality that goes a long way to making the world a better place for everybody.”

A few months after joining LA Galaxy, Robbie Rogers tweeted a picture of a message left by teammate Landon Donovan on the wall of the dressing room. It said, ‘Saturday after the game, mandatory night out… players only (no wives, gfs, bfs, side pieces).’ The note was a show of solidarity, one that mattered a great deal to Rogers who posted it the words ‘Thanks for including me.’

“I thought there would be more out athletes at this point,” he says today on remaining the only openly gay, man playing top-flight football anywhere in the world. “My first year I found it very difficult and struggled a lot with it. Now I don’t think of myself as a gay athlete but just a member of the MLS Cup winning LA Galaxy and kind of get on with my life.

“Being different in the sports world used to scare the shit out of me. Then I realised it made me special.”

Credits

Text Matthew Whitehouse

Photography Beau Grealy

Styling Nicolas Klam

Grooming Johnny Mckay at Frank Reps using Shu Uemura

Photography assistent Bummy

Digital technician Ross Morrison

Styling assistent Ali Miller.

Robbie wears jacket Louis Vuitton, t-shirt Bassike and Jeans G-Star.