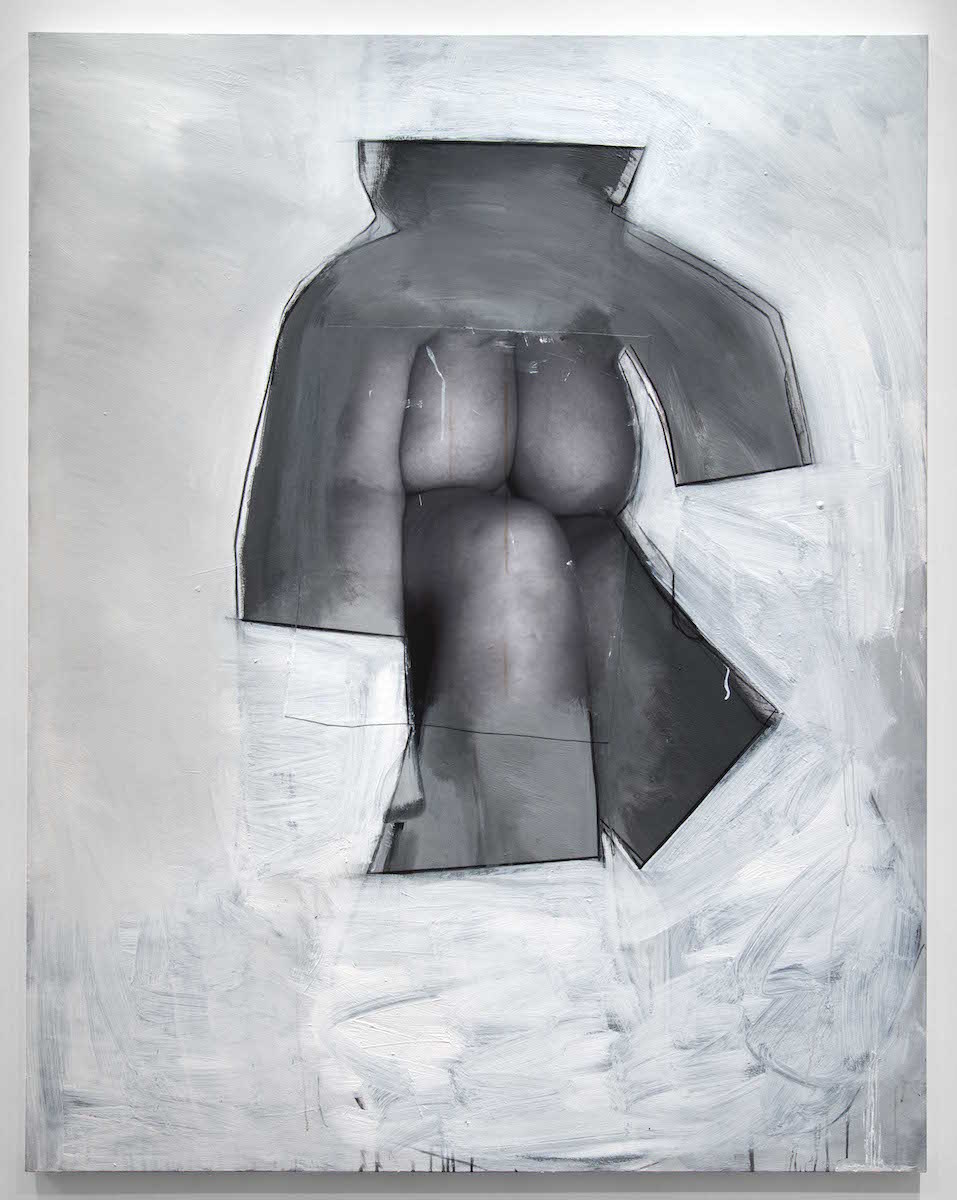

Richard Prince has a new show of female nudes opening today, titled “The Figures,” at Luxembourg & Dayan, New York. The work involves him taking inkjet prints of curvaceous naked girls and layering paint and charcoal on the canvas until their bodies are turned into grey shapes, angular and mechanical. The press release explains that Prince was inspired by the age-old practice of figure drawing. The only part of the girl’s photographed body that remains visible is a floating piece of flesh: a butt, a breast, a thigh. Prince’s images are the latest in a (very) long art historical tradition of men representing the female form in proprietary, even violent ways. As somewhat of a repeat offender, Prince previously appropriated other’s work in his “New Portraits” series last year.

In Pablo Picasso’s painting Nude Woman in Red Armchair (1932), a bright, blonde girl relaxes, totally naked except for a thread of beads around her neck. In Picasso’s signature style, her body is made up of a series of disjointed shapes: her breasts are round, harsh circles, her fleshy arms unattached to her torso. She is curvaceous, sensual, and unsettling. She looks off into the distance in a kind of sad way, as if she knows she is being cut up, as if she can feel herself floating away.

The woman in the painting is Marie-Thérèse Walter, Picasso’s lover and model. They met when Marie-Thérèse was only seventeen – Picasso was forty-five and married. They had a passionate, secret affair, and Marie-Thérèse eventually became pregnant with his child. Despite their ongoing relationship, they never lived together or went public. Four years after Picasso died, Marie-Thérèse Walter committed suicide by hanging herself in her garage.

It’s hard to find a representation of the female form in art that isn’t also an object of violence. As evidenced by original sad girl Marie-Thérèse, there is a thin line between abstraction and amputation. Throughout the history of painting, girls have been dissected and then rebuilt by the male painter, until they are barely recognizable. Look at Picasso’s disfigured female faces, or Willem de Kooning’s gruesome women with bared teeth, or even Ryder Ripps‘ digitally deformed Instagram pin-ups. Sometimes it seems like a girl can only be represented as a sleepy sex object or a terrifying monster (or a confusing combination of the two); she is either unconscious or inhuman, and always, unavoidably, nude, or about to be. Similarly, I feel at times like I have to choose between those two options in my own life, dancing between desires, desires that I can’t quite place as others’ or my own. Will I be a boss bitch or a chill babe? Do I get to keep my clothes on either way?

While figure drawing has been a foundational part of artistic training since the 13th century and earlier, it’s only a relatively recent development that women are allowed to participate. Girls were long barred from seeing the naked model – but paradoxically, not barred from being one. It wasn’t until the late 1800s that female painters were allowed into life drawing classes, and even then, the model had to be mostly covered. Without access to source material, the types of paintings women could make were limited: they turned to still lifes, landscapes, portraiture. Girls possessed a naked body, but they were not allowed to paint them, at least in public.

I like to think that the female painters of history snuck in representations of themselves in more metaphoric, disembodied ways: it’s hard to look at Judith Leyster’s Tulip (1643) or Louise Moillon’s Cup of Cherries and Melon (1633) and not think that girls have always been talking about themselves and their bodies – just maybe not in the same language as you.

There isn’t just one history of painting. There is the one of Picassos and Princes: one where the female body is assumed to be always available, an object of pleasure or beauty that can be cut up, laid down, pinned this way or that. And there is one of resistance: one where girl artists take possession of their own representation, undoing wrongful ideals, throwing off tired expectations. The history of Mary Cassat, Hanna Wilke, Ana Mendieta, Lorna Simpson. To reduce the female body to a “figure,” a set of measurements, a papery image, may be an art historical precedent — but it’s a history that is begging to be re-written.

Credits

Text Audrey Wollen

Image courtesy Luxembourg & Dayan