French-Iranian artist Chalisée Naamani has porous Parisian and Persian roots. Her practice is similarly hybrid: collaging artisanal materials, reinventing textiles, and rethinking iconography and memorabilia. It’s also hugely shaped by the socio-political turmoil in Iran. “We are full of hope and despair at the same time,” she says, intently following the repression of protestors and their bravery from her native Paris. “It’s hard to watch a young generation make sacrifices, but what’s happening is powerful.”

She carries her identity with pride, and although during her studies at the prestigious Beaux-Arts de Paris she worried about being boxed in, today she is relieved to transcend an exclusively Westernised view of the world. “I walked on Persian rugs my whole childhood, played marbles on them, and eventually they became a kind of workspace, as I placed images on the rug to compose them and photograph them,” she recalls. “I grew up with rugs as wall hangings. My relationship to the tableau is really by way of tapestry… My dad always told me when kings traveled in the desert, they missed flowers and vegetation, and that’s why they wove rugs with floral motifs. Iran is not just carpets or pistachios or saffron, but these references have shaped my gaze.”

The Pierre Cardin garment bag she integrated into her debut solo exhibition in 2021 belonged to her grandfather; he’d bought it in Paris and carried it back to Tehran. Her mother would later return it to France when she emigrated there, and now Chalisée has regenerated it once more. Her new solo show at Milan’s Ciaccia Levi, Quando va male, il leopardo, is named after something Jean Touitou, the designer of APC, allegedly said when he collaborated with Kanye West a little less than a decade ago. Kanye thought the French designer’s suggestion to use animal prints had racist connotations. Touitou reassured him, saying: “Not at all! There’s an Italian adage: quando va male, il leopardo — when things are going wrong, reach for leopard print.” (“I love this,” Chalisée enthuses over its absurdity.) Her Italian-born gallerist didn’t know the expression, and isn’t sure if it’s a real thing. “It would be funny if it was just an urban legend,” she laughs.

In her studio, she was working on a mix of new work and existing pieces Chalisée has re-conceived, like a voluminous wedding dress shown back to front with “you are not hard to love” written across it. She was also toying with an orange-lined bomber jacket inside out, noting that the orange hue was systematically used to locate pilots involved in crashes. “Nothing is random!” she says gleefully. She delights in the long history of fashion: like knowing that mercenaries who returned from battle patched up their torn clothes with high-end materials to celebrate their victorious survival, or the codpiece-like “padded flies” that highlight the coqueterie in masculine fashion of the 16th-century French monarchy. Ultimately, her work is a study of surface: “My works are very pictorial — I want them to be read like paintings,” Chalisée says.

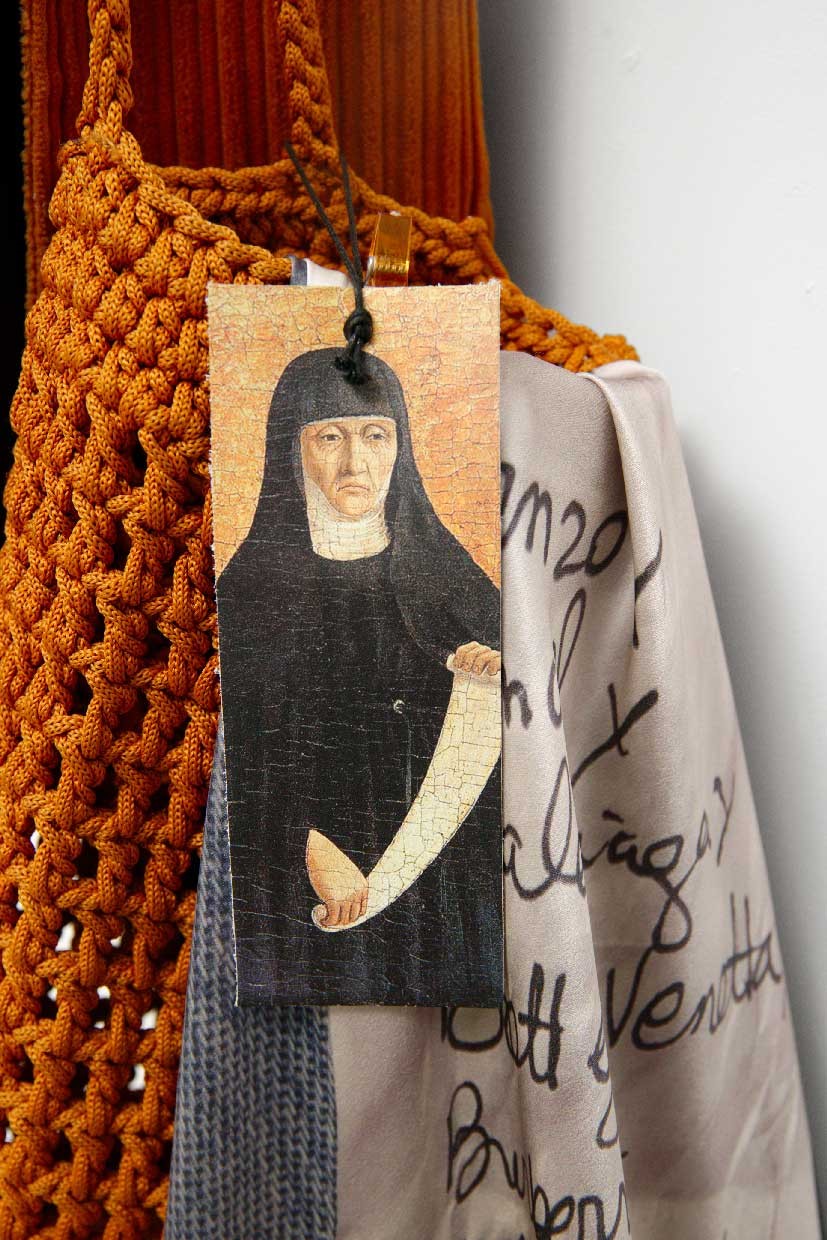

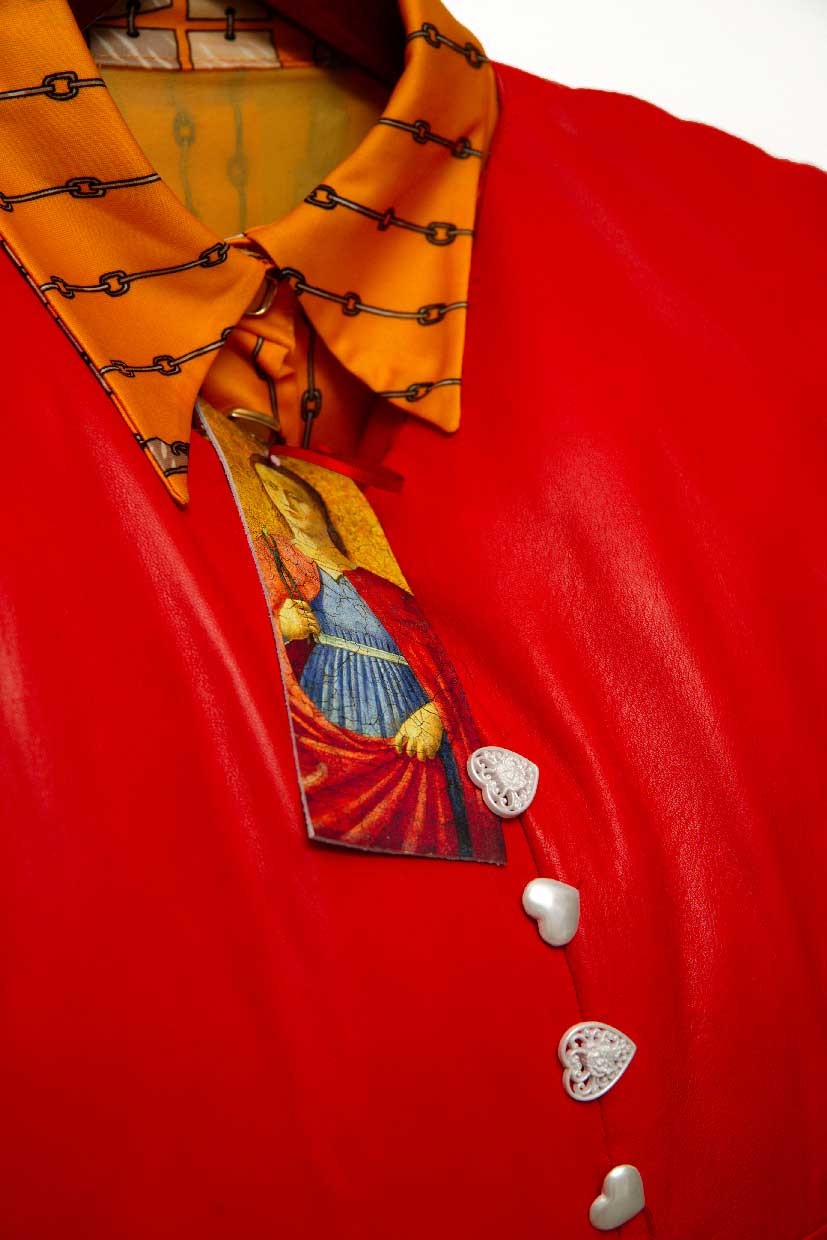

No matter the project, Chalisée’s process begins with the notebook in which she has long collected phrases she loves — be it Lady Gaga quotes, lines from Batman movies, or the ways in which her brother mocks her — from which she begins to craft a maquette in Photoshop. From there, she hand-sews together pieces she’s collected or bought, either solo in her studio in Montreuil or assisted by her mom at home. Her work brings together the most diverse materiality: printed PVC tarps, mirrors, souvenir store gadgets, boxing gloves, judge’s robes, liturgical garments, lycra, found foulards, tracksuits, metal rings, pendants. She exuberantly dabbles in a high/low patchwork as she mixes the likes of Comme des Garçons with the beloved, now-shuttered French discount department store, Tati.

“I’ve always loved the act of getting dressed,” Chalisée says. “In Iran — even more so since the Revolution — there’s this split between indoors and outdoors, and thus the importance of getting dressed to go out. My parents brought that perspective with them to Paris. I grew up with this amour du vêtement — a love of clothing. My mom always told us to be well-dressed. Of course there’s a political aspect there too: ‘Be presentable. Wear layers, so you’re not stigmatised.’”

For her, politics and aesthetics work together implicitly. Her piece “Cape et Gilet Jaune” or “Cape and Yellow Jacket”, incorporates the symbol of the contemporary French gilet jaune political movement. For an installation around the World Cup, she used the Qatari soccer jersey, highlighting how sponsorship and branding function as signifiers that both unite and divide. She uses tartan kilts to evoke the legacy of Vivienne Westwood and Alexander McQueen, as well as manga and the sexualised school uniform. “I don’t like the term ‘political art’ — I find it kind of absurd, in fact. For me, culture is political,” she says. “I create beautiful forms and tell stories. Those stories are steeped in politics, because I’m a woman with Iranian origins who lives in Paris.”

“It’s not that I don’t want things to change,” she clarifies, “but my intention isn’t to revolutionise anything. I’m just offering a way of thinking.” Moreover, given how layered her pieces are, she knows a lot of information she presents might go unnoticed. “That’s the enigmatic thing about a work of art — you can’t read everything in it. In fact, you can misread a work entirely… But that’s what’s interesting: I put the work out here, and then I leave. I’m not anyone’s guide.”

Quando va male, il leopardo runs at Milan’s Ciaccia Levi Gallery until 20 May.

Credits

All images courtesy of the artist and Ciaccia Levi, Paris-Milan