After rising to power in 1979, Margaret Thatcher spent the next decade planting seeds of neoliberalism that would have devastating consequences for decades to come. With the Thatcher regime promulgating free trade, open markets, privatisation and deregulation, multinational corporations rose to the fore, increasing inequality and environmental destruction in the UK and developing countries around the globe.

During Thatcher’s tenure, state-run industries closed, resulting in the decline of the north, destroying the power bases of trade unions. As the balance between public and private ownership veered sharply to the latter, the “mixed economy” that helped shape political consensus after the war came to a crashing end. Ideological divisions were further sharpened by the rise of media baron Rupert Murdoch, who was backed by Thatcher, setting the nation on a dismal course.

Across the pond, president Ronald Reagan forged a similar path for the United States. The birds of a feather quickly became a formidable pair, fostering a transatlantic alliance that championed British and American exceptionalism at the expense of all who crossed their paths. Reagan first established his antipathy against the left while serving as governor of California from 1967-1975, ordering militarised campaigns against anti-war protesters and the Black Panther Party.

In response, artists, activists and musicians joined forces to push back, using their collective work to fight the power and create change. From the roots of the 60s counterculture and the DIY ethos of 70s punk, a new generation of rebels and radicals emerged in the 80s. With the advent of MTV, commercial enterprises dominated the industry, as artists became brands unto themselves. But not everyone was willing to sell their soul.

During the 80s, a host of alternative rock subgenres including post-punk, grunge, and noise rock took root across the US and UK. In 1988, Billboard took notice of the rising underground bands and added the “alternative” category to chart the sales of this disparate collective of anti-pop artists whose fame grew through word of mouth rather than corporate marketing schemes. Rather than cater to mainstream tastes, the musicians preferred to collaborate with likeminded indie labels and perform for hardcore fan bases in small clubs — which is where British photographer Richard Davis encountered them.

After dropping out of school at age 16 in 1982, Richard fell into photography while taking a course at the Birmingham Trades Council’s Centre for the Unemployed. Filled with a sense of purpose, the teen turned his attention to the issues facing the working class at the time. “We had the riots of 1981 and 1985, the Falklands War, the ongoing troubles in Ireland, high unemployment, poor living conditions, and a criminal neglect of the poor,” he remembers. “But what really got me involved and engaged with politics was the Miners Strike of 1984-85.”

Thatcher called the miners and their supporters “the enemy within” — a label Richard has worn with pride ever since. “The Miners Strike showed me how powerful photography could be in reporting the truth,” he says. “Even one striking image could say more than a thousand words in conveying a message. Photography played an important role in highlighting injustices or poor conditions especially for the working classes who normally didn’t get a voice or were just ignored.”

Inspired by the work of Don McCullin, Gordon Parks, Larry Clark, Mary Ellen Marks and Diane Arbus, Richard began chronicling Birmingham before securing a job teaching photography at Manchester Polytechnic in 1988. At the school he was warned to avoid Hulme — a neighbourhood he first saw through the eyes of Kevin Cummins, who photographed Joy Division there in 1980. Invariably, the prohibition only stoked his curiosity. “The first time I set eyes on Hulme, it provoked a combination of fear and awe,” Richard recalls.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

Mesmerised by the brutalist architecture set against a stark, graffiti covered landscape, he immediately felt drawn to the community of outsiders living there. “By the 80s, Manchester City Council had moved most families out of Hulme, leaving the place half empty,” he says. “What was left occupied tended to be students, ex-students, drop outs, punks, travellers and the unemployed — basically anyone on the fringes of mainstream society, which created a vibe, [that was] very much ‘us and them’.”

Six months later, Richard secured a squat at 257 Charles Barry Crescent. “In typical Hulme style, I got the key in one of the local pubs,” he explains. “Harry Stafford, who was in Manchester band the Inca Babies, was moving out and wanted someone he knew to move in so they could forward all his mail onto him. It was a perfect set up for me, I only had to pay the electricity bill and that was it. Free accommodation.”

With the money he saved on rent, Richard funnelled all of his funds into photography, setting up a photo studio and darkroom in his flat — which was mere walking distance from the clubs and gigs in Manchester City Centre. “Talk about right place, right time!” he says of the fabled “Madchester” era.

“The end of the 80s was an inspiring time for a lot of young people,” he says. “The Thatcher years created an outsider syndrome that fostered an alternative culture. On top of that, Eastern Europe was starting to open up and the apartheid regime in South Africa was under pressure to release Nelson Mandela from prison. We had the Poll Tax Riots in this country. The people were rising up and you got the sense the Tories were running out of steam. There was a positive outlook and it felt like things were finally starting to change for the better.”

Cafés, pubs and clubs became vital spaces for connections, creativity, and community, fostering significant shifts in the culture. “Manchester was full of artists, poets, painters, musicians — young people doing many, many things — so I had an environment that completely motivated me,” Richard says. “I was in my early 20s, meeting all these creative people, and that energy rubbed off on me.”

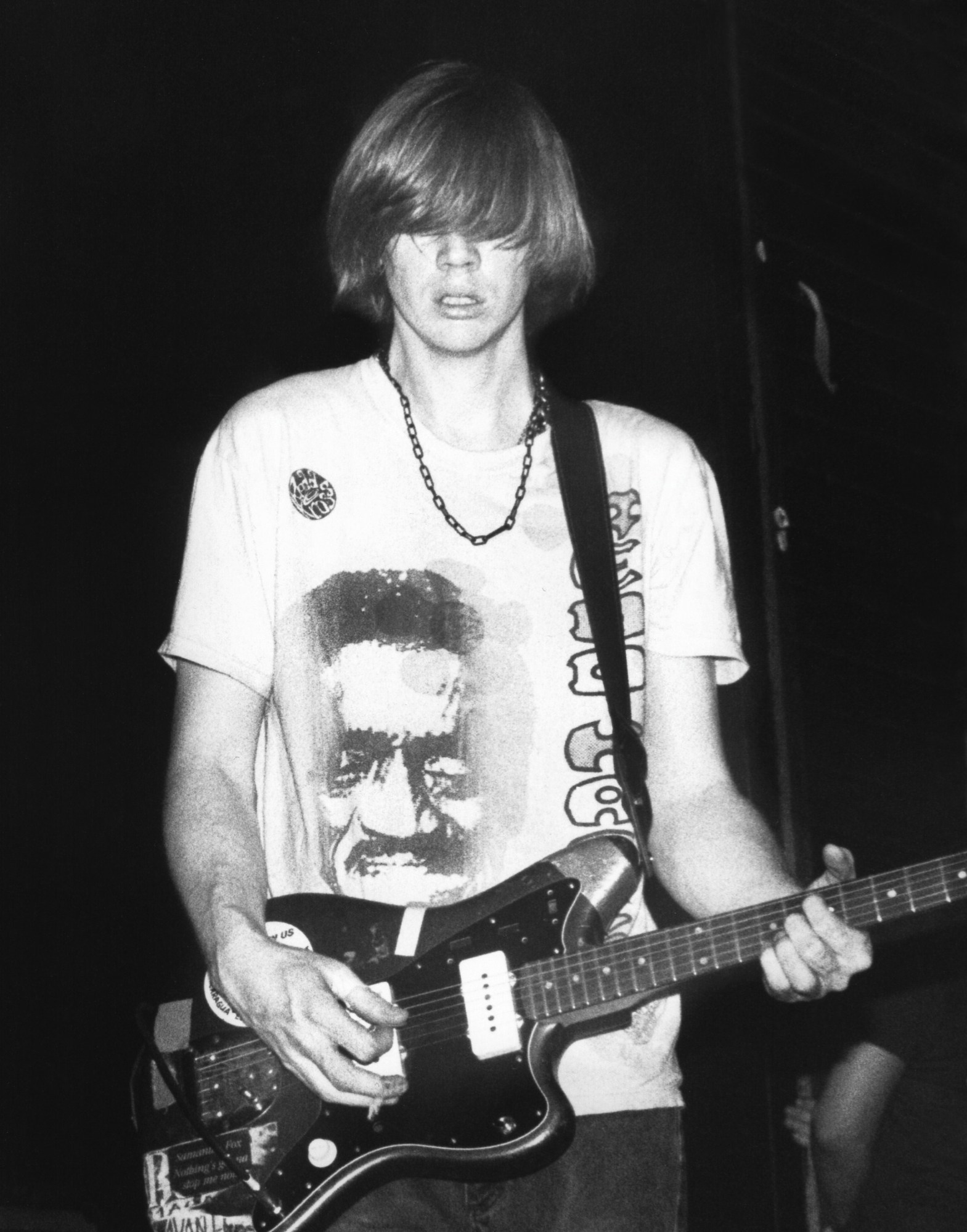

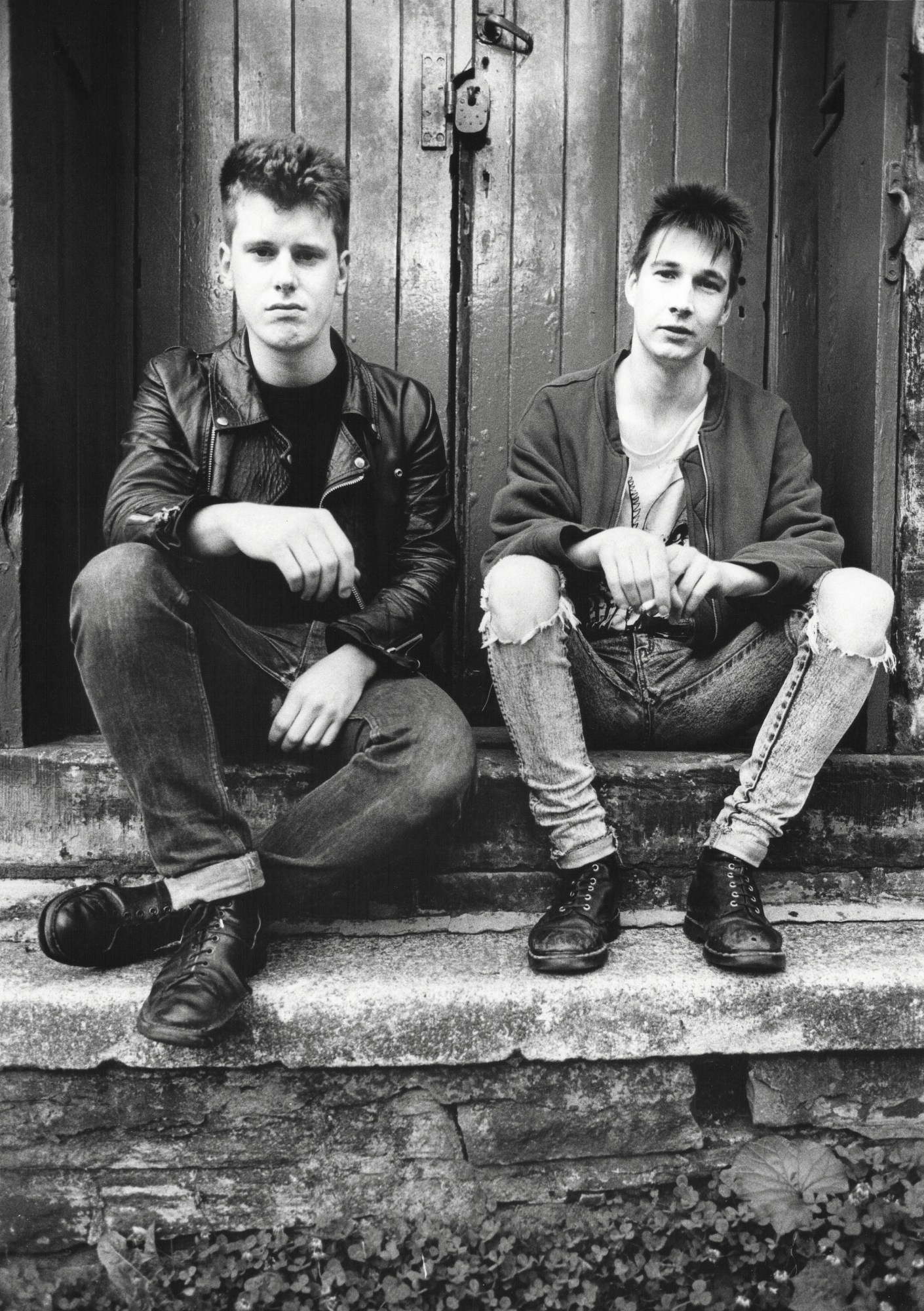

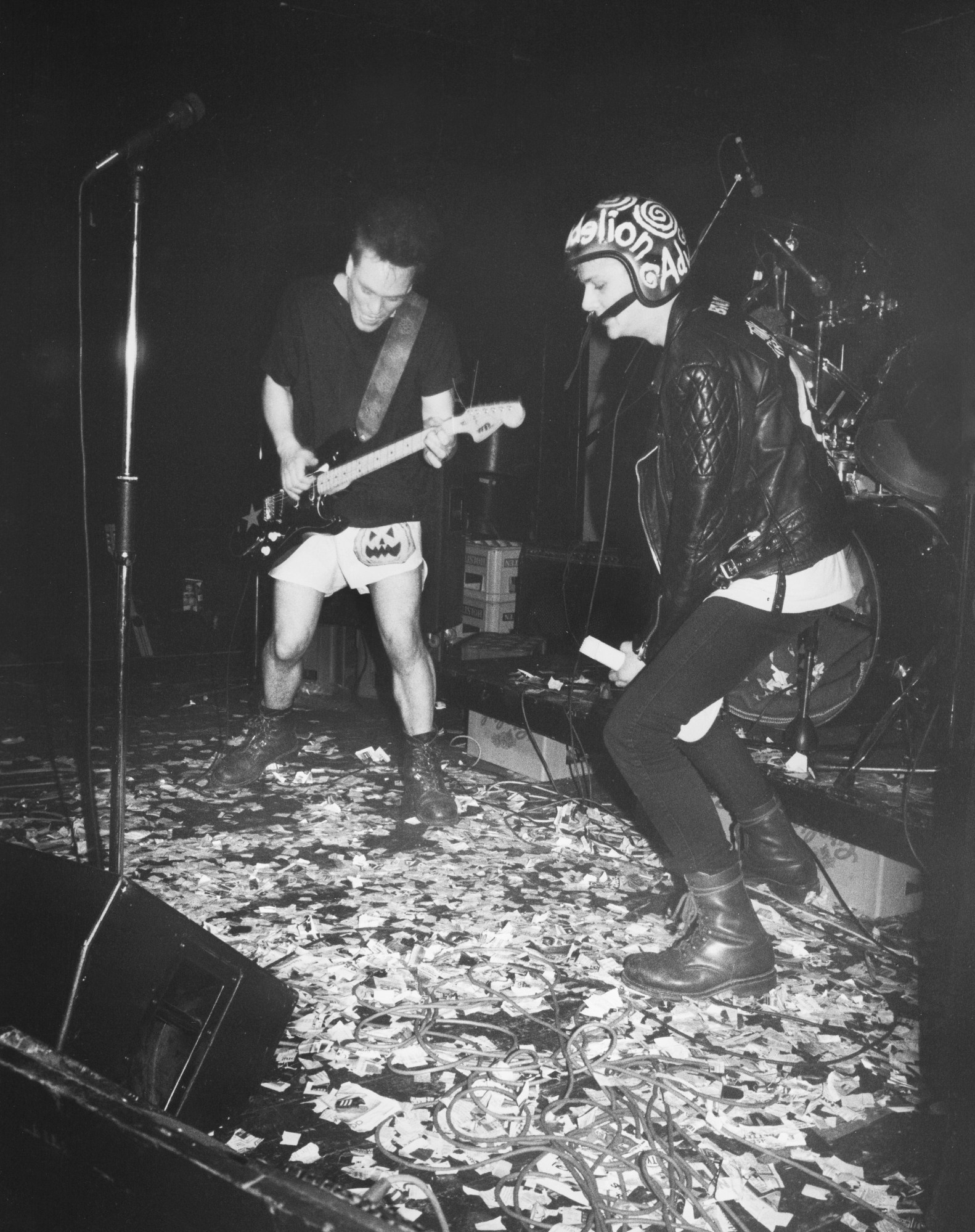

In the new book The Post-Punk Years 1987–1990 (Café Royal Books), Richard brings together photos of Nirvana, Fugazi, Thurston Moore, Kim Gordon, Björk, and Nick Cave made during that pivotal era. “I used to be out virtually every night,” he remembers. “I didn’t get a lot of sleep for years. I did burn out badly at the end but I look back and there’s nothing I regret because I was in the heart of the city at a critical time. Quite often I was the only photographer at the gigs, so I had access to the bands.”

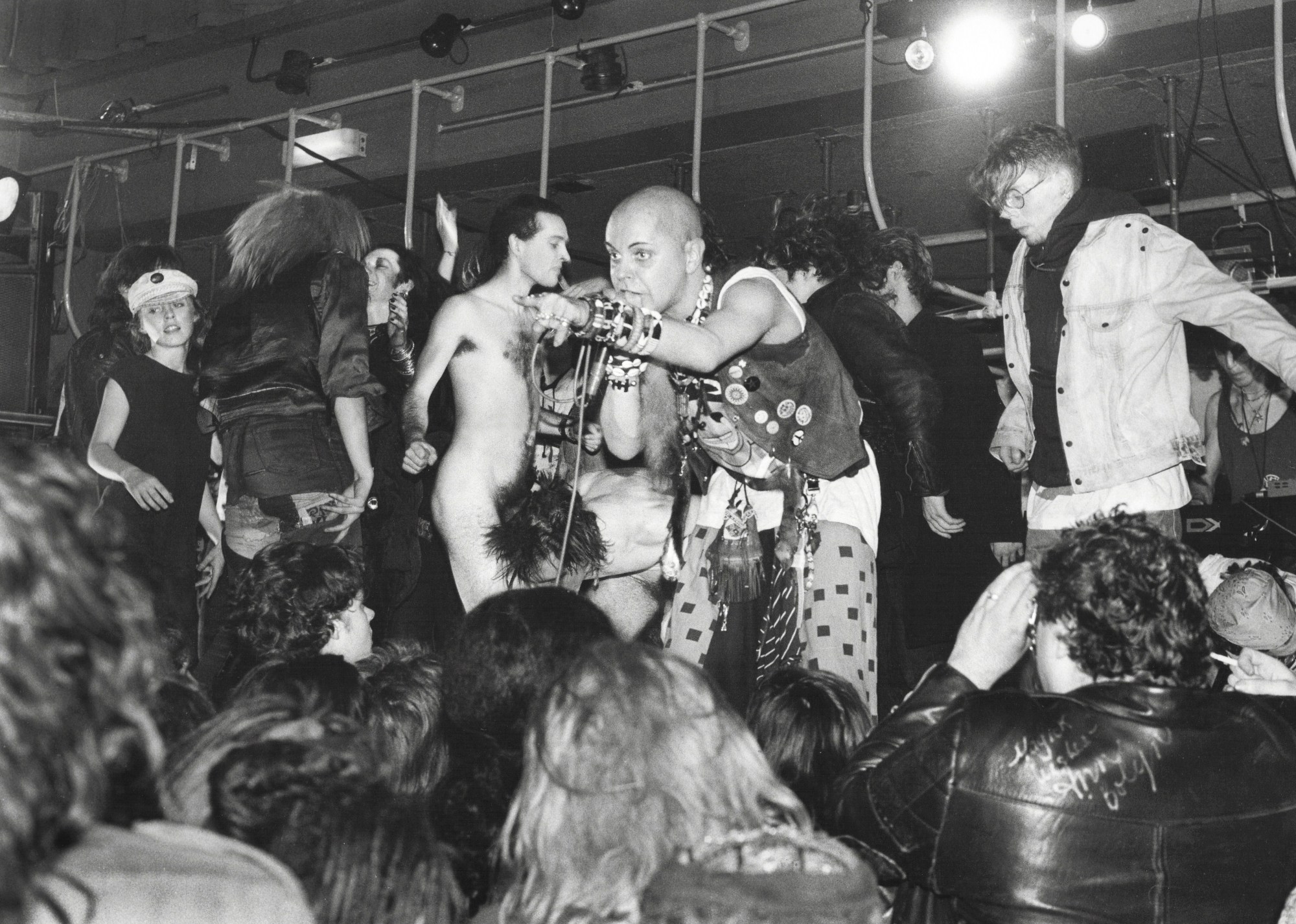

Richard could freely stand right next to the stage photographing bands like Nirvana, Sonic Youth, The Sugarcubes, and Pussy Galore as long as he liked, or hang out with bands like Mudhoney backstage without having to deal with agents, managers, and publicists. The bands of this era stood firmly against the squadron of corporate functionaries and rules that now dominate the industry.

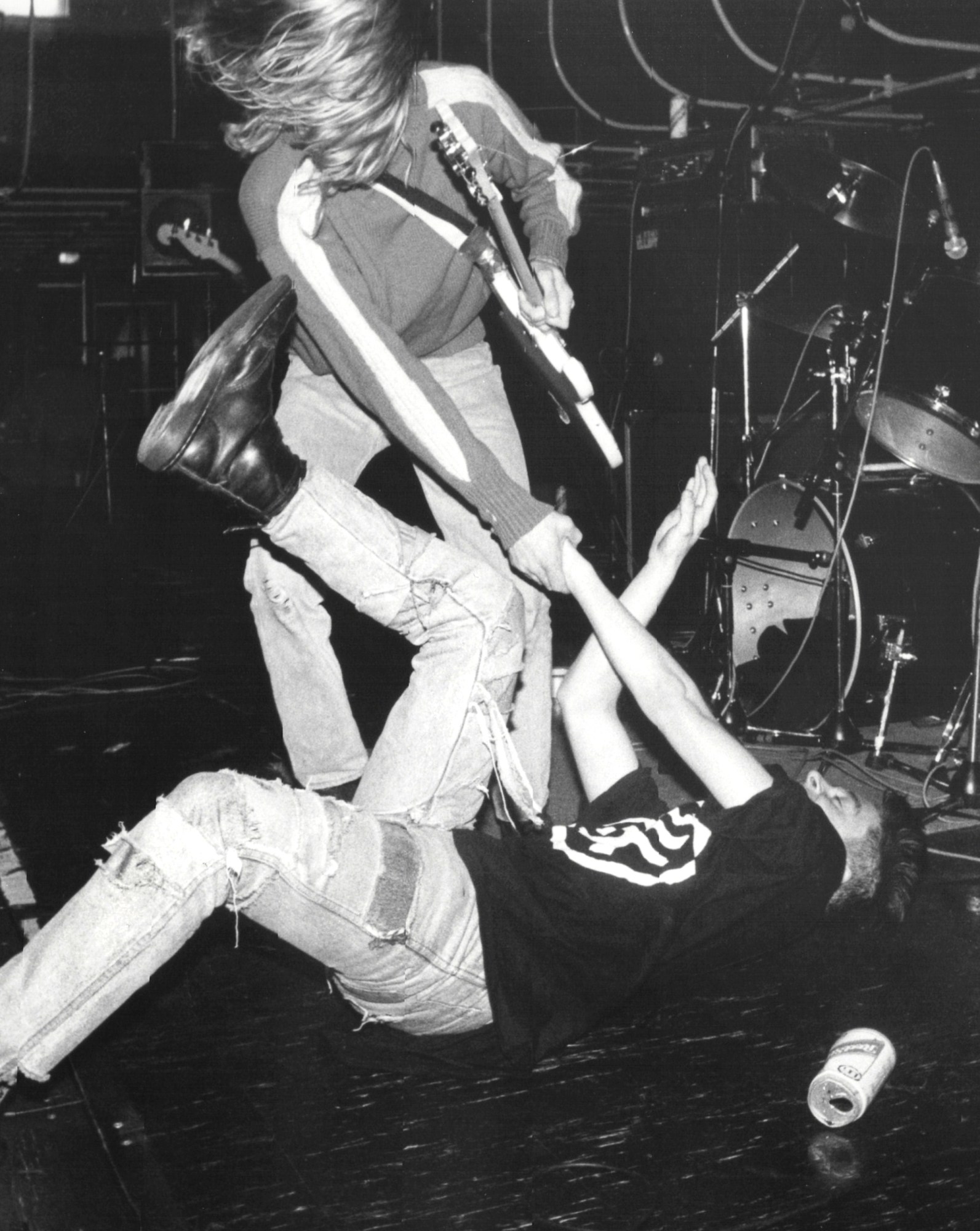

“They gigged at very small venues and there were no barriers at all. There were no people telling you ‘You can’t stand there’ or ‘You can’t do that,’” Richard says. “If you keep things low key, you get more of an atmosphere. There’s no gap between the crowd and the band but once things get too big, you lose so much. Things are so clean and proper these days. I miss when everything was loose and a little chaotic. It felt real. Once the corporate money people get involved, they ruin things. They don’t want things to be dangerous. Everything is too controlled.”

Richard points to the Sex Pistols, Jimi Hendrix and the Velvet Underground as the artists who smashed their guitars, lit them on fire or simply disbanded live on stage without so much as consulting management in advance. “I don’t think a lot of people in the past were bothered about careers,” he says. “Most people were out to have a good time and make a statement. It was wild.”

The Post-Punk Years 1987-1990 is out now, published by Café Royal Books.

Credits

All photos courtesy Richard Davis