Growing up in Maryland to Haitian parents, Marcus Brutus’s longstanding affection for the arts started with trips to the National Gallery of the Arts in D.C. Although he always loved to draw, he started sharing his work on social media while working as a PR assistant. He kept up this creative practice and eventually got recognition from a professional artist, the validation pushing him to pursue his own painting professionally. He dropped everything but art when he landed gallery representation and his first solo show in 2018.

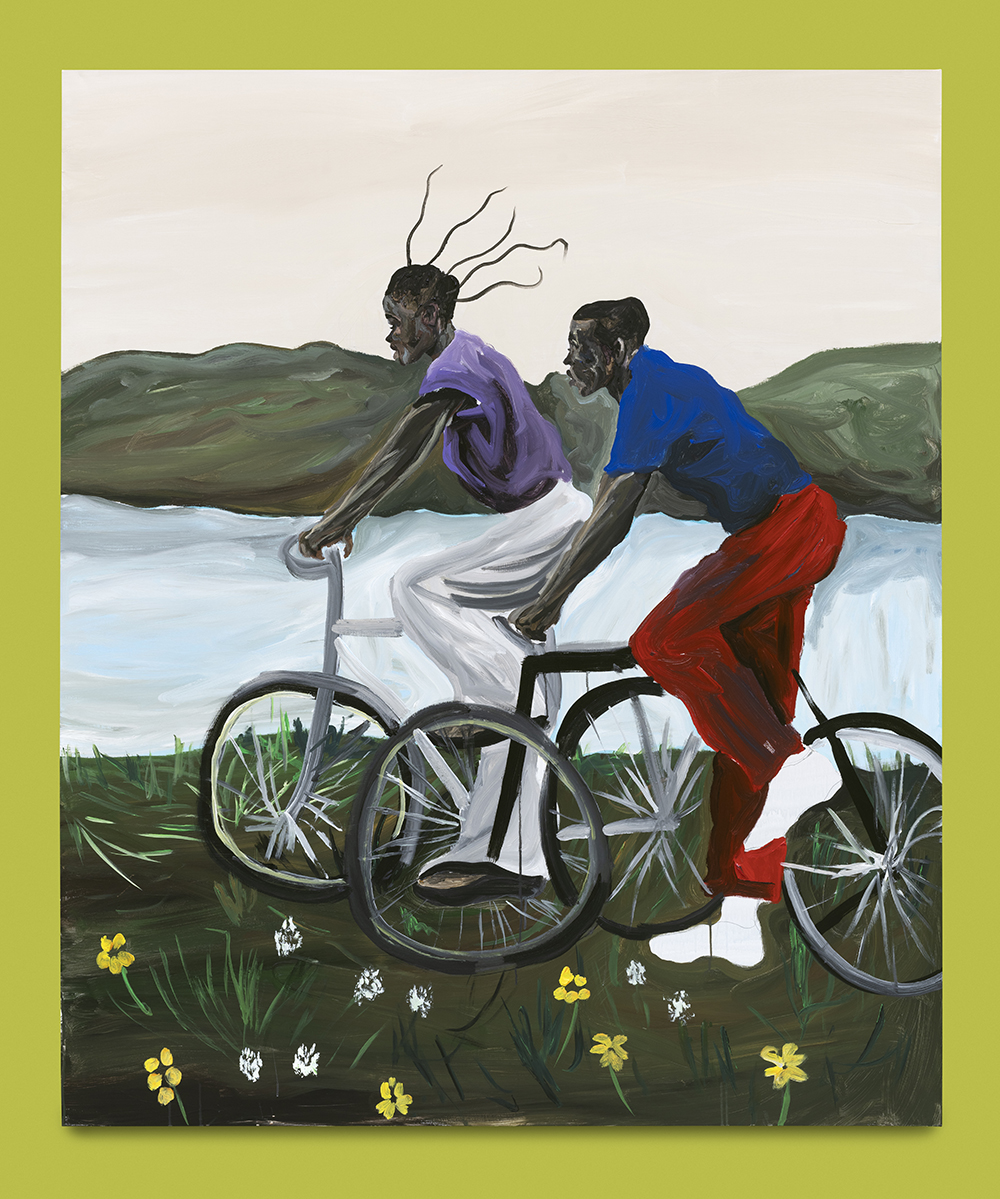

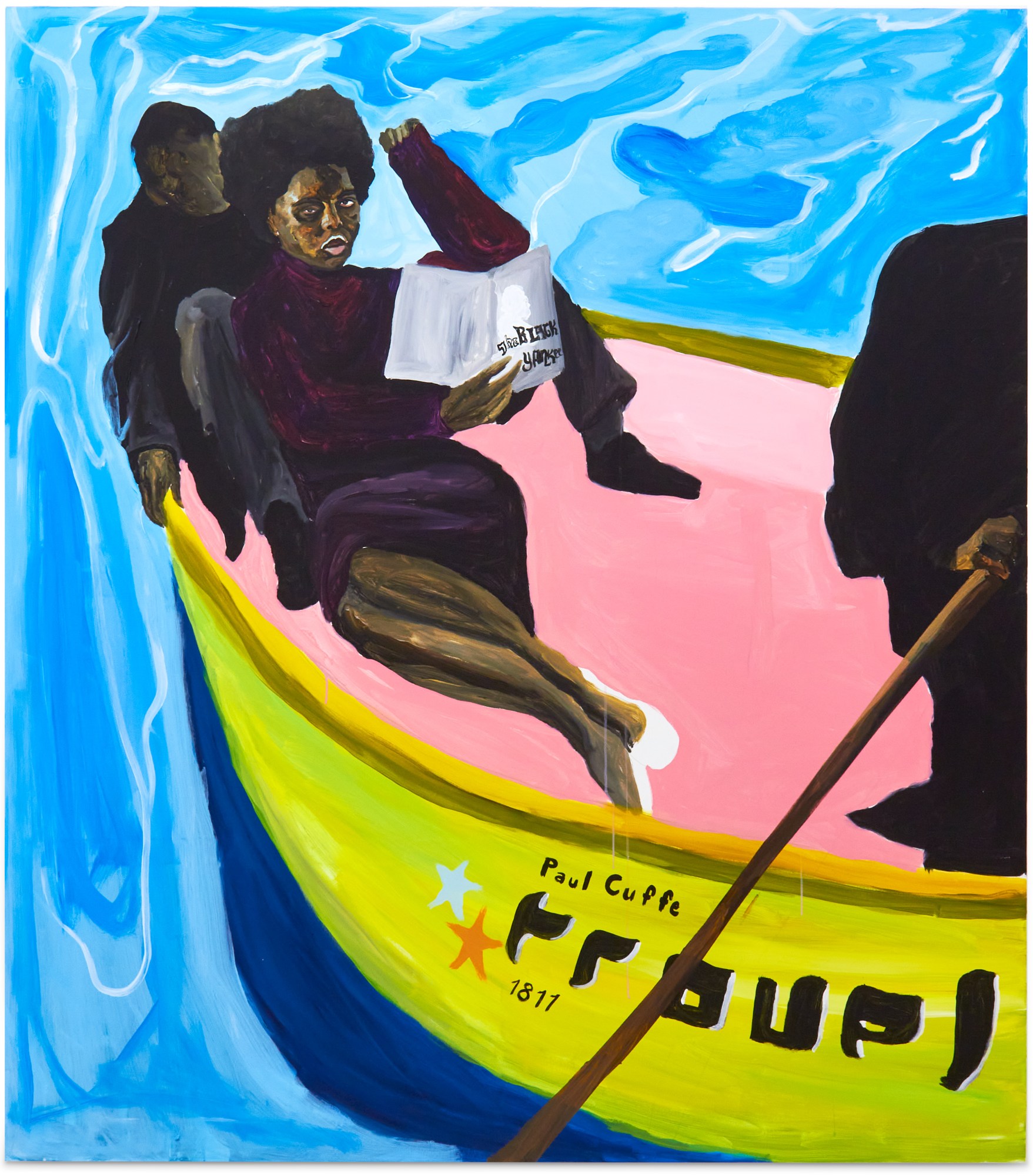

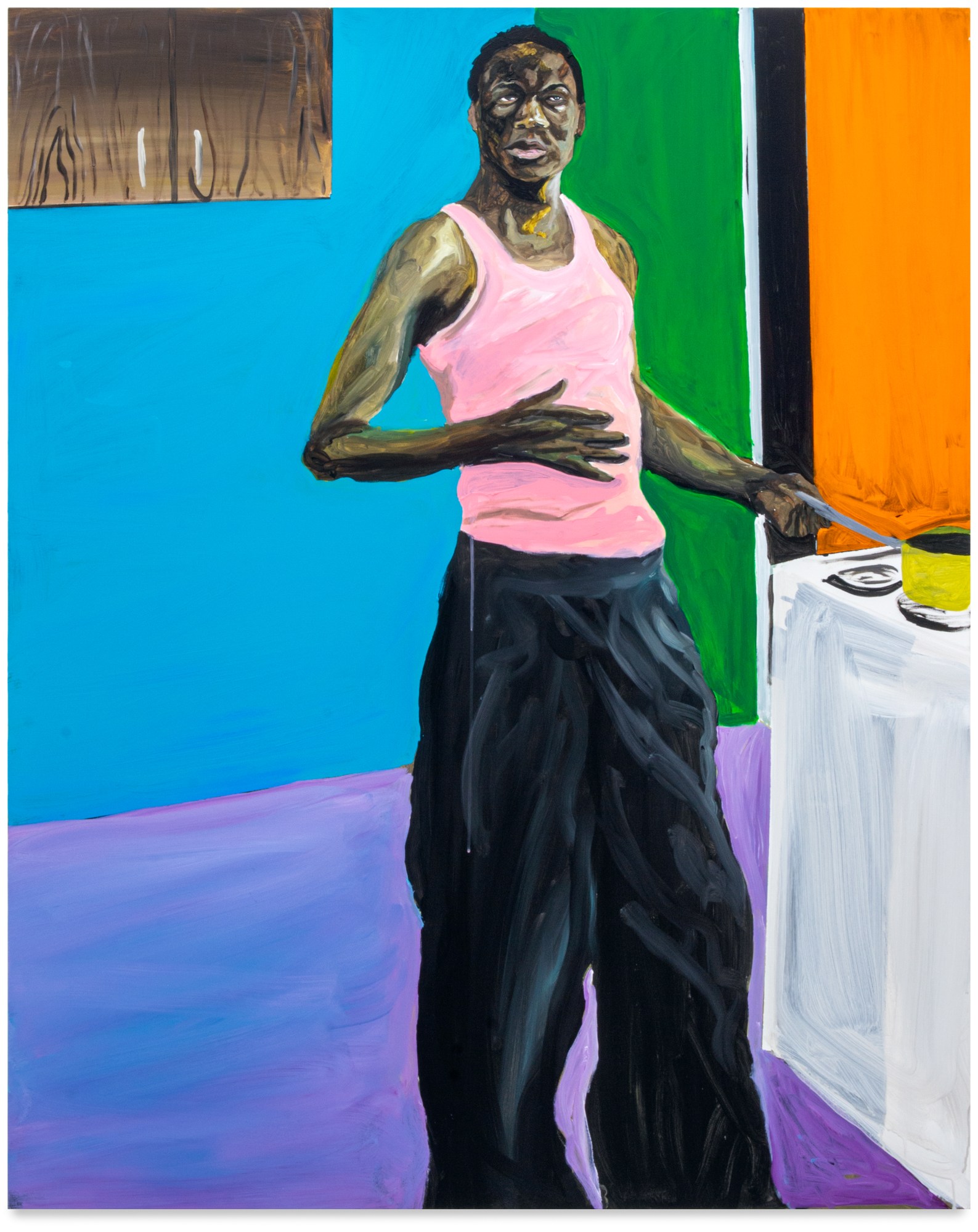

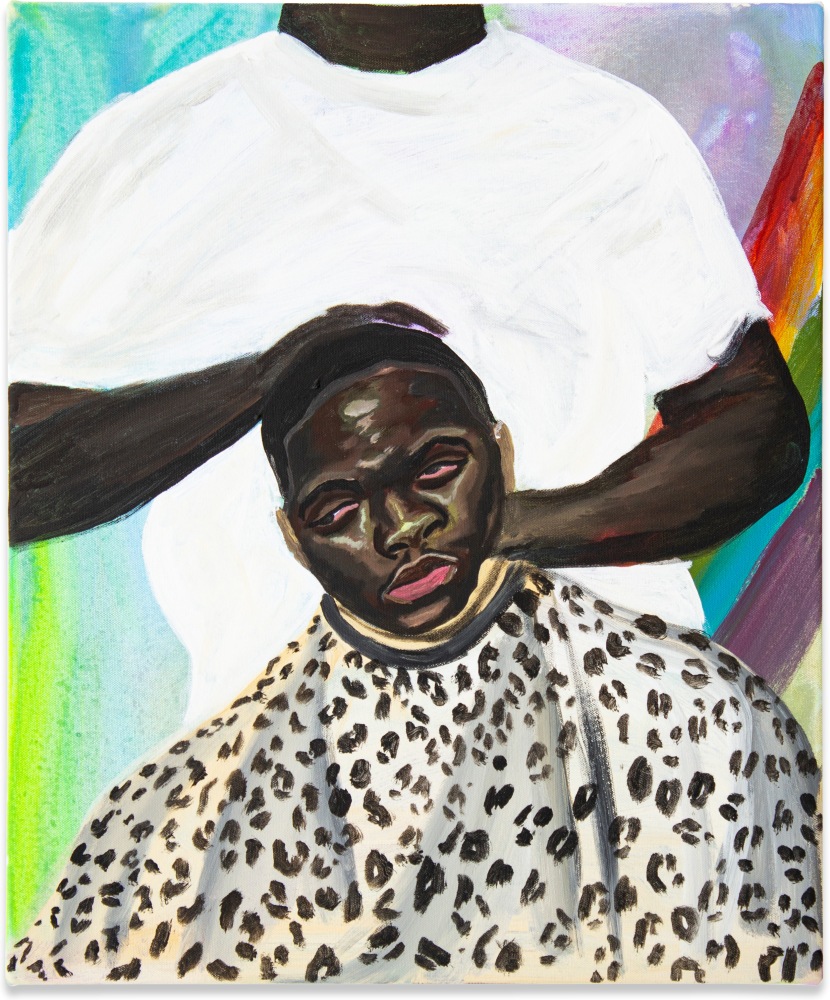

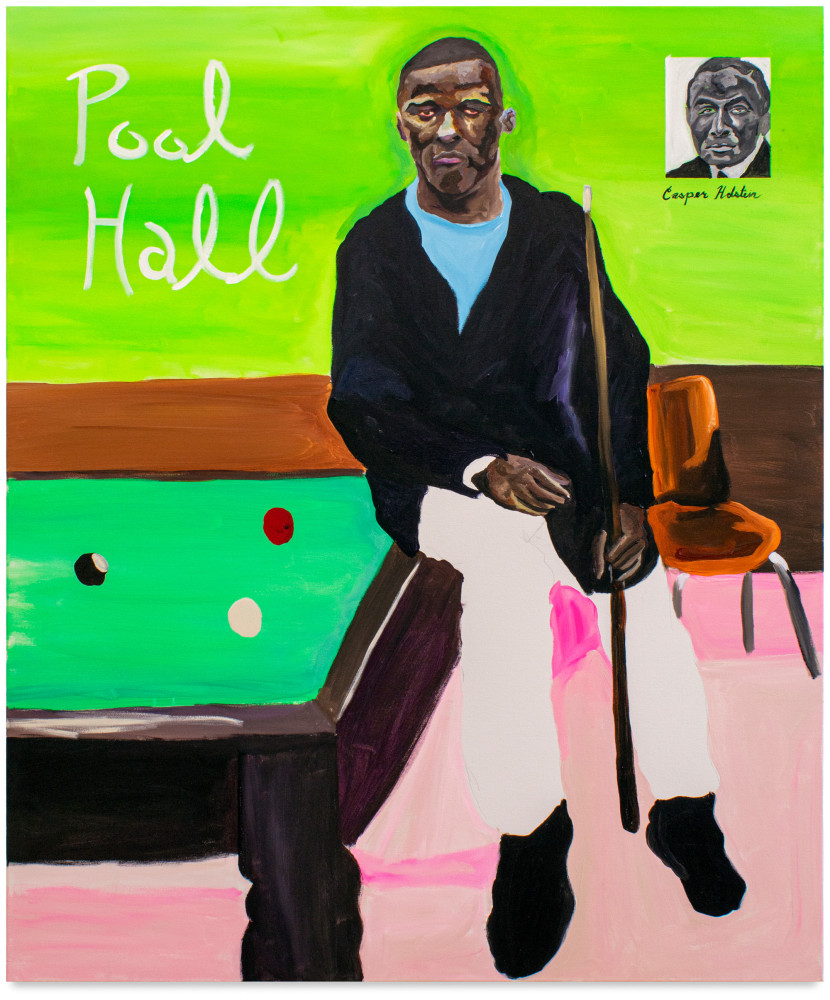

These days Marcus calls New York home and has done for over 15 years, labouring on his figurative work in a studio in Greenpoint. His paintings pull from quotidian scenes of Black life — expressed in vivifying colors and loose brushstrokes — as well as fashion and pop culture. His subjects are composites from brand campaigns, diasporic stories, urban surfaces, African history, computer screengrabs, and elaborate vintage coifs. His first monograph, published in 2019, featured an essay by powerhouse curator Antwaun Sargent. A recent solo exhibition, Poetics of Exile, at Stems Gallery in Paris, had his paintings of Black leisure in boats and on bicycles hung against a very eye-catching chartreuse backdrop.

Speaking from his studio, Marcus shared how he arrived at storytelling through fashion, being drawn to his Haitian heritage, and examining the set design of The Sopranos for his new work.

Does living and working in New York influence your painting?

I couldn’t imagine living anywhere else. I used to walk around a bit more, but the older I’ve gotten, the more indoors I’ve been. Seeing a painted wall, or even a poster that’s starting to decay, things like that… There’s texture to the city. I don’t like when things look too clean or flat, so that kind of plays a role for me.

What is your process of gathering references that lead up to the act of painting?

Initially, I start with a very vague idea of the subject. Once I’m able to get in a groove, the images come immediately. I can’t stay fixated while watching a movie — I’m pausing it all the time and taking quick pictures on my phone, like every night. And then in the morning, on the way to my studio, I will assemble the images together for the next painting. Fashion editorials too, because there’s so much drama within those images. But I focus on taking random screenshots, because I don’t want to be directly referencing specific art. I want all of the references to almost exist in the public domain, so that I’m not taking from someone else’s vision. I want to ultimately make it my own.

Regarding fashion: could talk a bit more about that influence? You designed a logo for KITH, and you’ve done a painting of Telfar Clemens for Vogue…

Initially, I went to school to study public relations. When I graduated, I worked for a year and a half at a fashion PR agency. We worked with several brands: Kenzo, Rodarte… I was working with Nike at the time. So that was my initial entry into the fashion world, and my interest was always the storytelling element. I love reading the press releases, and how they would build a collection. That is directly how I build an image: It’s about the storyboarding.

Did you ever think about designing clothes or creating textiles?

No… I’m much more of a consumer. When I was younger, I used to doodle things that I wanted, like if there were cool sneakers — my parents would never buy me these kinds of things — I would always create what I wanted that already existed.

Trying to manifest by drawing! Speaking of manifesting, I saw your exhibition in Paris, which showcased your most recent work… Tell me about making it.

The exhibition was titled Poetics of Exile. I was born in the US, but both my parents are Haitian immigrants. I went to a French school from the ages of five to 10. France has such a significant role historically for me. So I wanted to focus on the fact that I don’t have a singular identity. Like most Haitians — or the ones who no longer live in Haiti, because it’s almost a failed state at the moment — you don’t have this real sense of home: you exist in multiple spaces.

I had this book of old African hairstyles from the 70s: I would open it up and just pick, like, a random hairstyle to add. Then some of the images would come from Western fashion magazines. So it was just this blend that reflects my point of view.

Can you talk about that title, Poetics of Exile? It’s very powerful.

It’s a genre of poetry. A lot of the titles for the paintings came from poems. There’s this book I was reading over the summer, before I started working on the paintings, called A Place in the Sun, which focused on the Haitian community in Montreal, Canada, and how all of them were exiled during [Haitian President] Duvalier’s reign, because they were viewed as enemies of the state. A lot of them were intellectuals, doctors, scientists and people in prominent roles in Haiti. As soon as they moved to Canada, they were relegated to very working-class positions, but they still formed these communities. There were many writers or thinkers that I was introduced to in that book. There’s a chapter titled “Poetics of Exile” in there. Before I even started working on the paintings, I was like, this is what the title of my exhibition is going to be.

In terms of the references, what is the expected trickle-down to the viewer experience?

I like to operate with ambiguity. I want people to just look at the work and focus on the essence of humanity through this particular prism. It doesn’t really matter to me if people understand the reference or not. It’s not necessary. I want the references to exist almost like back in the day of buying a CD: when you read through the booklet and see who worked on the music.

On Instagram, you create slideshows of work, and influential references pop up at the end of them. How does social media serve as a complement to what you’re doing in a gallery space or in a book?

In 2018, when I had my very first solo exhibition, I was sending the gallery PDFs of the works. I was like, how are they going to really speak to collectors about what I’m doing? So for each painting, I would create this collage to break down all the elements. But then I just started doing that, ever since. Instead of posting a painting just like that, I thought it would be interesting to show how I use references to create. A lot of times, in portraiture, it becomes about who the person in the work is… but for me, it’s not about that, ever. For figures or characters — a lot of times I just use the same faces that I come across over and over again.

In a previous interview, you talked about wanting to represent a collective Black experience. Can you talk about finding something that resonates in this communal way? How do you identify, and portray, that moment?

I take interest in the history and experiences of Black people throughout the world. There’s no borders to it. I’m interested in people in the Caribbean and South America, throughout Africa, Asia. I like to reference things from wherever. I was essentially saying everything that deals with history interests and influences me.

Even with overarching commonalities, if you’re showing work in New York versus even Paris, the national discourses around race can be really different. Have you had reactions from people that surprised you, that reveal the ways in which locations change the narrative around your work?

Definitely. For instance, at the beginning, the language around my work was always “depicting everyday African-American” — the usage of African-American, which I accept, felt a bit limiting, because I’m looking at the world. So it includes African-American, but it’s also, you know, Black people in Europe and Western Africans, North Africans, and so forth. When I was in Paris, some of the things referenced were from Senegal and a lot of people there understood it immediately. Here, it’s focused on the Black American experience, and New York has a big Caribbean population, so that will be understood here.

As contemporary conversations around race change and evolve, do you see your work as participating in that? Or do you feel like it doesn’t have this political thrust?

It definitely can be. I want to somehow capture the human essence in the work but also challenge the viewer to be able to relate or connect to themes and stories that, on the surface, look different than their own. I’m interested in connecting with everyone because that is the same thing that we ask of minorities, immigrants, refugees wherever they go in the world. It’s something that we should all be capable of doing, regardless of where we’re from, our background, and so forth.

What are you working on now?

Right now, I have a painting that’s part of an exhibition called When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting in South Africa at Zeitz MOCAA. Other than that, I’m in the process of working on new paintings, all centered on interiors, and interiors that open onto landscapes, like through windows. I was really interested in psychoanalysis and therapy, and any sort of uniqueness when it enters into a Black context. I started to focus on The Sopranos — there’s so many therapy sessions there.

Do you work on several paintings simultaneously, or is it a one-to-one situation?

I would just work on one painting at a time and just knock them out; I would paint fairly quickly. But now I’m painting really slowly. I’ve been jumping from painting to painting; it’s like working on a group rather than singular images. I want to actually think of them as works that really coexist and live with each other and respond to each other.

Credits

All images courtesy of the artist