“I think your hands tell so much about you,” artist Taylor Simmons tells me, as we peruse a selection of paintings in his Brooklyn basement studio. “Those hands whooped my ass for about two days,” he says, pointing to a work in progress depicting a dancing figure. Though he might be meticulous, he admits he’s never really been interested in proportional perfection. “If you look at it and you feel the rhythm of what’s going on, that says it’s successful. More so than if everything was exact.”

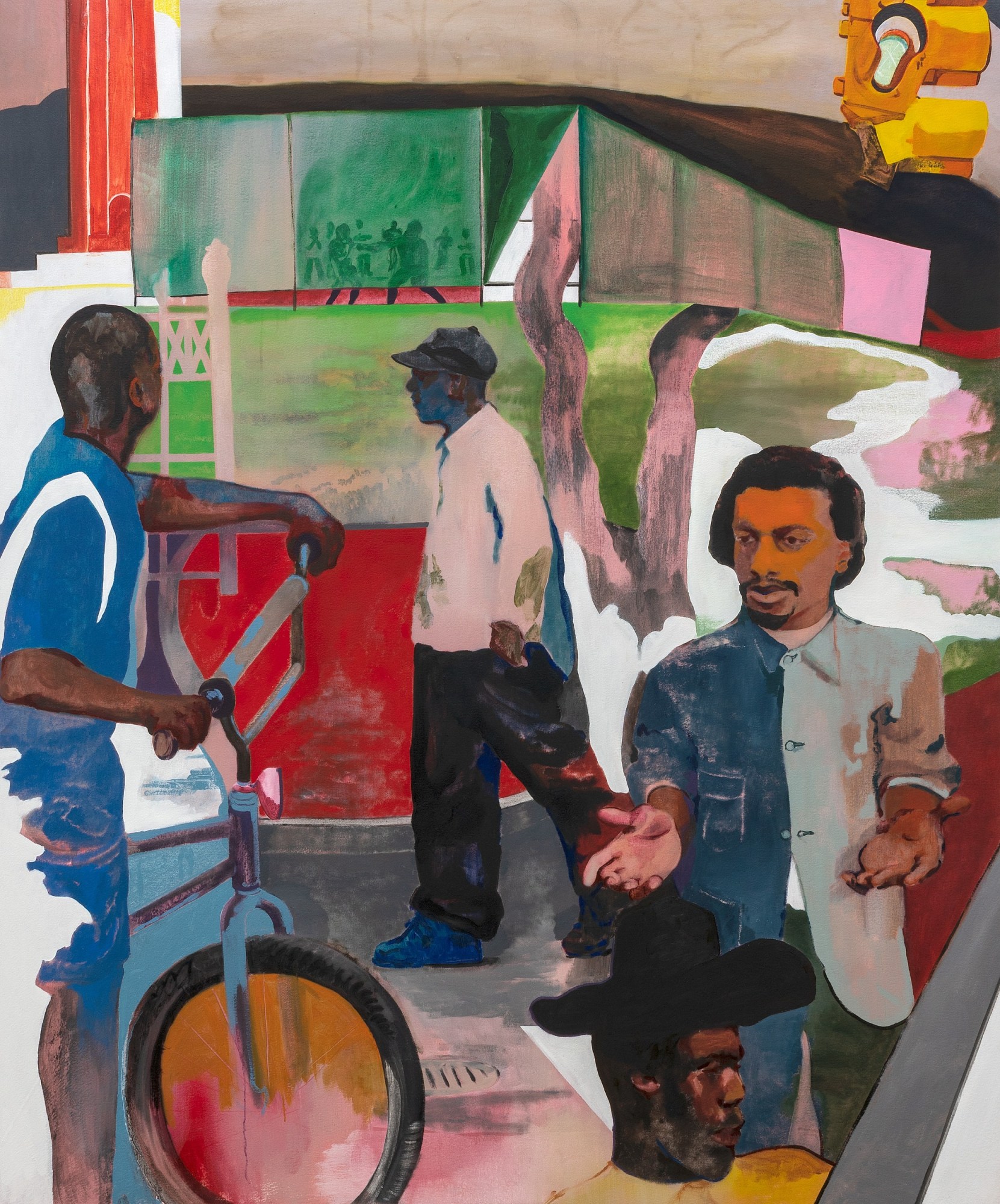

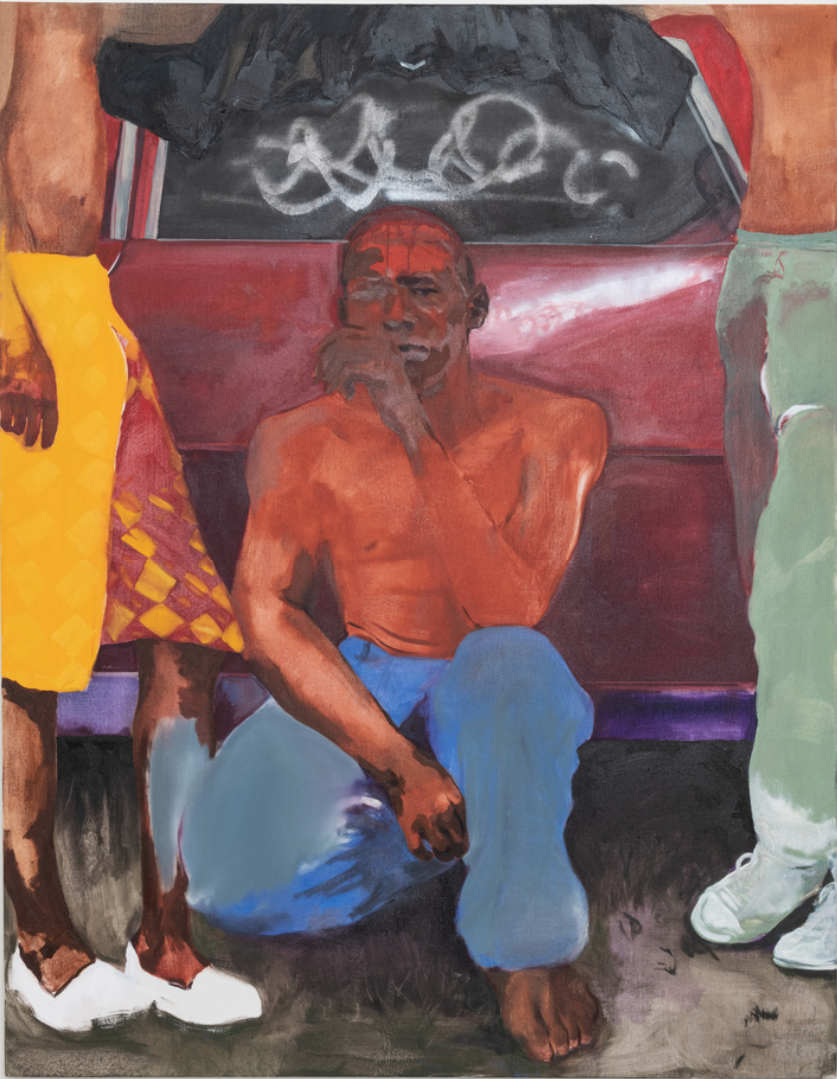

For Taylor, painting is just as much about the process of discovery as the final outcome. His research involves scouring the internet for archival photographs of Black life and culture. “A lot of times, I’ll go digging on eBay,” he says. “I’m used to seeing stuff from like the 60s, 50s, 40s — but now people are starting to do 80s and 90s. I’m really into southern culture from that era, because I grew up in the 90s. I’ll go look up old cookout photos, because they’re very rich. It’s just somebody’s barbecue photos, but the further removed we are, the more precious it feels.”

Growing up in Atlanta, he remembers experiencing Black culture from different angles. When he was still in elementary school, his parents moved from the city to a more rural area just outside. Initially, he found himself newly surrounded by white neighbors and classmates. “When I first moved out there, my first friend and I would hang out all the time in school. One day he came up to me and was like, ‘We can’t hang out anymore. My parent’s said I’m allergic to you’.” Soon the area saw an influx of Black residents also expanding from the city center, which also meant new sources of inspiration. “When Black folks actually started to move out there, it was exciting because the music was different, the style was different, everything was different. I was finally seeing people that looked like me.”

This is when he first found himself interested in fashion, tapping into the now-iconic style trends (think jerseys, white “tall tees”, sweatbands, baggy jean shorts, etc.) coming up from the American south at that moment in the early 00s. “My tees were so tall, oh my God,” he says, laughing. He found it fascinating that clothes could help him locate minute differences across the broader Atlanta cultural landscape, and realized that those details are often overlooked in Black culture. “I think about how many books there are documenting white subcultures, like punk. We have the same niches in the Black community, it just doesn’t have names, so it’s not as celebrated or documented. Honestly, we need a Black version of Wolfgang Tillmans,” he says. “I think that’s why I focus so much on body and clothes in my paintings, because those little signifiers are super important. If you look at old Renaissance paintings, the way someone was dressed was always so important. It showed who they were.”

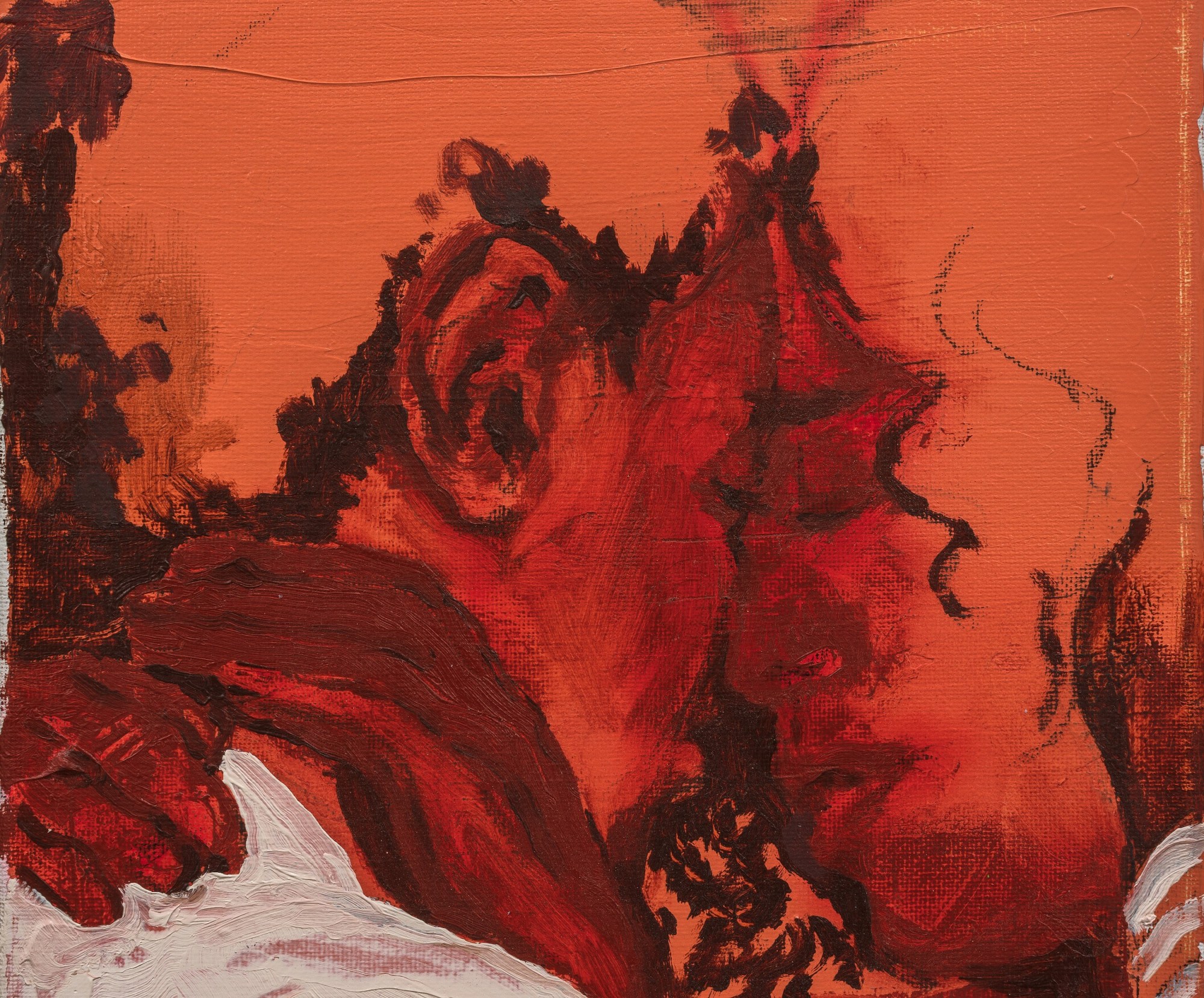

The act of archiving and memorializing under-documented pockets of history is central to Taylor’s creative practice — his work excavates his childhood to make meaning of histories both shared and personal. Those memories are legible on the canvas through details like his use of the color red instead of shades of grey to communicate shadow. He explains stumbling upon “L’Atelier Rouge” — Matisse’s 1911 painting of his studio. “I love that red, the dirt in Georgia is that same red. It’s iron oxide. That color has always spoken to me. It feels very warm and has a lot of history to it. It’s nostalgic for me.”

This instinct toward indulging nostalgia also serves as a tool to explore his own sense of change and growth. In one instance, memories of a school dance became a vehicle for re-examining his relationship to masculinity, a trope that reappears across his body of work. At high school parties, dancing with a girl was the ultimate show of dominance, but while she twerked, “your boys would hold you up,” he explains. “It’s like a tender moment — one friend holding up another friend.” In that world, “a man can only really touch or support another man in these instances. So I thought I’d make a painting of it.”

Taylor went to Savannah College of Art and Design to study comic books and storyboarding, which might point to the cinematic quality of his works. “I grew up loving Dragon Ball Z. As that evolved, I got into manga and comic books. Basically narrative and stories,” he says. “It still kind of sits in my work now, but I like to leave it a little bit more vague so that the viewer can decide what’s going on. I’m not telling you what’s happening. You get to decide.”

He’s noticed that people from different backgrounds will come up with different answers informed by varying points of view. “I painted this gang member for my solo show. Homie’s got the face tattoos, and he’s throwing gang signs,” he says. “People that saw it here, and kind of knew what it was. But in London people were like, ‘Is that a monk?’, because he’s bald. I thought it was really interesting, because gang members do share certain things with monks. They have rules. They have a brotherhood. We think of gang members as being bad, but they are just trying to survive in their community.”

Though he’s already exhibited in his first solo show last spring, Everything All at Once at London’s Public Gallery, Taylor has only recently shifted into painting full-time. He’d just moved to New York City from Atlanta when the pandemic hit, giving him time and space to focus on developing his talent. Then he got into a serious bicycle accident that changed his entire trajectory. “I had this reckoning: life is really short. I was like, all right, let me actually pursue this.”

Now that he’s consistently showing in exhibitions from New York to London, he’s reflecting on how to stay centred in the midst of success. He often refers back to the words of one of his heroes for guidance. “There is this old David Hammons interview I found, and he says something like, you can tell when an artist is making work to be loved, and when they’re making something that is just the spirit speaking through them,” he says. “That stuck with me. If I’m thinking about it too much, I’m trying to be loved. If I’m just painting, it’s real. It’s true. It flows. It’s just me moving. I’m not asking for permission.”

Credits

Photography Jay Izzard

Artwork images courtesy of the artist and Public Gallery, London.