“When we say ‘she has such great style,’ we mean the clothes, but not just the clothes. We also mean the sensibility that chose the clothes, and the body that found the clothes to suit it and move inside it,” art historian Alexander Nagel told author Sheila Heti in the anthology Women in Clothes.

MIRROR MIRROR – Fashion & the Psyche confirms this take. The diptych exhibition encompasses two Belgian institutions: the MoMU Fashion Museum in Antwerp and the Dr. Guislain Museum in Ghent. Both examine — through their respective lenses — the fluid circularity of how fashion shapes our sense of personhood as readily as the inverse. The perspective is one of both body neutrality and curiosity: all the ways we can reframe the self via different materials, silhouettes, scales and abstractions.

With a subject this vast, there are necessarily omissions. Curator Elisa De Wyngaert, who conceptualized the MoMU sector, insisted that she did not want to be too literal in her approach: “I thought it was time not to focus just on the negative,” she said. “I didn’t want to show skinny models, to show that [fashion] can be harmful; I didn’t want to show ugly ad campaigns. I wanted to show artistic applications and bigger ideas [instead of] triggering images.” In preparation for this exhibition and its psychology framework, “I went to the Freud Museum and all these conferences and workshops and seminars. But then I thought, it has to be broader. I used the research quite minimally in the exhibition,” Elisa admitted, ultimately emphasizing: “you can use fashion to become someone else, or to find yourself.”

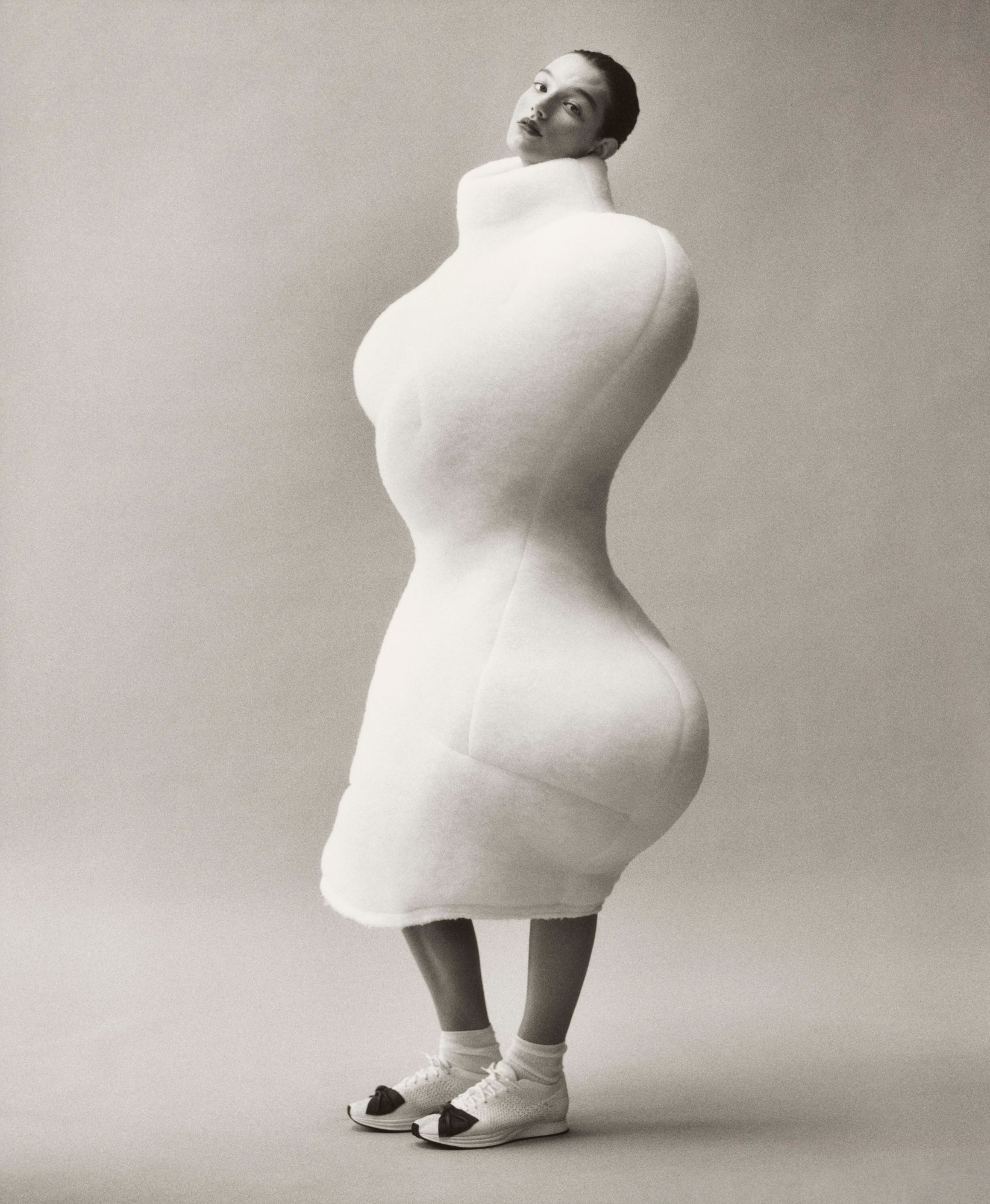

Elisa reached for pioneering designers like Comme des Garçons (“we’ve shown it before and we’ll keep showing it… it keeps shocking,” she noted), Belgian pillars like Walter Van Beirendonck and Margiela (of course), as well as ballooning skirts by Simone Rocha and protean designs by Hussein Chalayan. Scale is a central topic throughout. “I am fascinated by women trying to shrink themselves or take less and less space in a room,” Elisa says, noting the way Molly Goddard and Issey Miyake excel at forcing latitude through their voluminous creations. “We want power, we want equality, but then we are forced to make our body so small. It’s such a strange tension.”

Clothes and accessories are juxtaposed with works by artists like Tschabalala Self (who champions the Black body using collaged textile scraps), Hans Bellmer (whose perverse photographs subversively distort the body), Genesis Belanger (an uncanny installation of piecemeal body via macabre extremities) and Genieve Figgis (whose “Rococo caricature,” as Elisa put it, plays with historical idealizations of gender). If designers and artists work around the same topics, “I will always avoid making them illustrations of one another. We’ve never wanted to show an artwork that’s depicted on a dress,” Elisa clarified. “The emphasis is on creative people that have the same concerns about society.”

Those concerns about society have shifted to digital spaces: Elisa showcased how avatars highlight a new evolution in self-conceptions as well as cultural representation at large. “In the past, we’ve always said, fashion and magazines are dictating how women should look or what they should wear. But these days, the playing field is social media,” Elisa says. “TikTok and Instagram show fashions removed from [reality].”

For some people, this provides an inclusive environment, and the avatar allows one to become a fantastical icon, escaping the real world. “But on the other hand,” Elisa continues, “there is a very dark side to all these filters that can create a sort of Instagram dysmorphia or Snapchat dysmorphia. Because if you keep using filters… after a while, you wish that you looked like the filter. Younger and younger girls are using fillers and Botox and… that is directly linked to seeing these flawless features and faces constantly— and thinking that they look like that.”

Bodiless fashion is featured in the latter third of the exhibition, in which Balenciaga’s Afterworld: The Age of Tomorrow AW21 campaign (via video game development company Streamline Media Group) is shown alongside the jarring SS16 Louis Vuitton campaign. “I just ask questions of what the future will be like of these fashionable metaverse characters,” Elisa ponders.

The exhibition at Dr. Guislain Museum, by contrast, is as far from the metaverse as one can get, with the psyche made manifest through raw messaging. In the accompanying exhibition catalog, curator Yoon He Lamot wrote: “These designers do not design or sew a piece to simply wear it, but to live in it.”

The show is presented in Belgium’s first and oldest psychiatric hospital: the building itself was meant to be therapeutic, as the bars in the windows were subtly camouflaged to look decorative rather than imprisoning.

Yoon He’s selection and sourcing was informed by her familiarity with international collections and collectors of outsider art, although the opening installation by A.F. Vandevorst features loaned hospital furniture from the Dr. Guislain Museum for its international pop-ups in 2010.

Nearby, the exhibition spotlights the most infamous kind of clothing associated with psychiatry: straight jackets (or strong clothing, in UK parlance). The garment was made with the intention to calm down the body to then calm down the mind. It was “to make sure that the patients kept their dignity,” Yoon He noted, and prevent self-harm. Photographs from the series Held by Jane Fradgley — an English photographer who formerly worked in the fashion industry — highlights the end-of-the-19th century uniforms, which float eerily disembodied (and strangely elegant).

When patients were institutionalized, they had to give over their belongings, and received plain institutional dress. As the exhibition text affirms: “The objects and clothing were often used as a sign of resistance or as a way of dealing with the reality of confinement.” As a counter-measure, the garments were personalized by patients, doubling as an affirmation that their identity couldn’t be confiscated at the same time as their own clothes. A black wool coat from the 30s, demure on the outside, is seen to be exuberantly, meticulously embroidered and patchworked on the inside by an unnamed female patient who updated the designs regularly, like a diary. Clothes didn’t even have to be the canvas from which such artists worked: Giuseppe Versino repurposed rags and mops from his cleaning duties in an Italian institution in the early 20th century, knotting them into heavy draped tunics (they look like folkloric après-ski frocks).

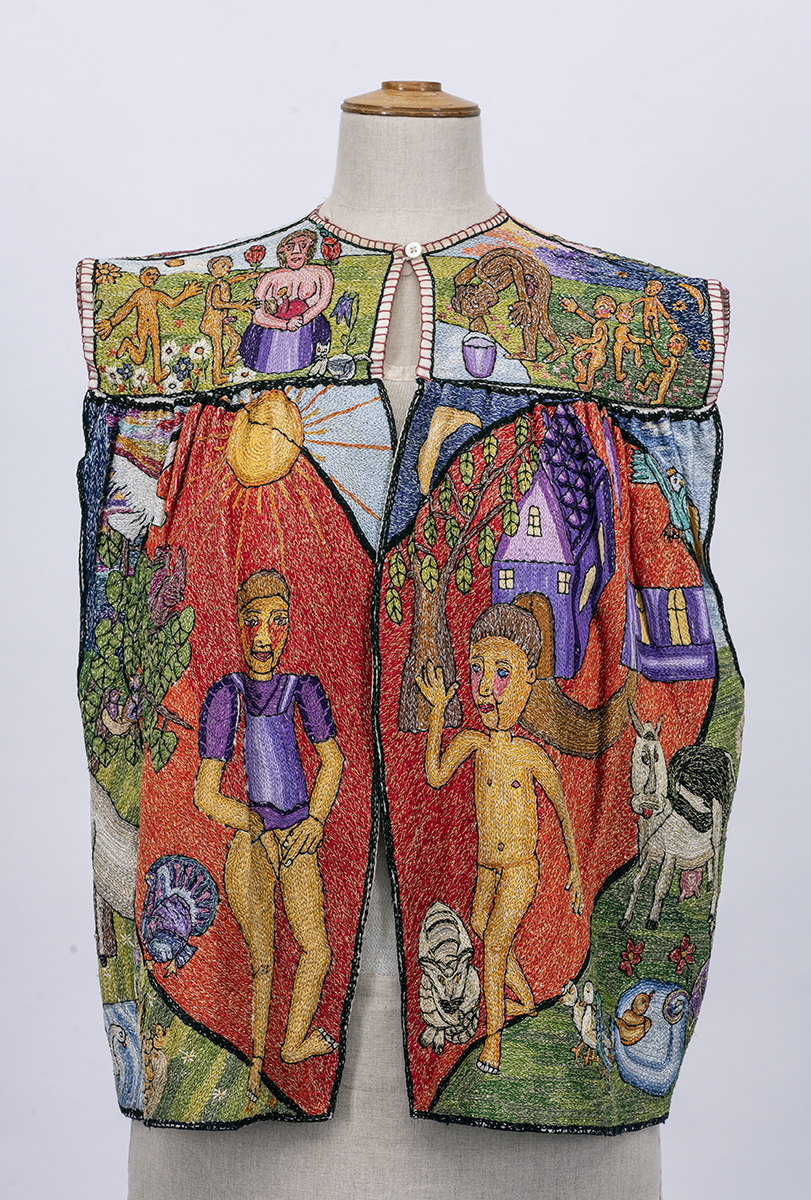

Some artists on display were not institutionalized but created work from the fringes of society and made clothing to signal their anxieties to others. Helga Sophia Goetze was a German artist who had been a housewife — until she took lovers and discovered her sexuality. Thereafter, she thought it was her mission to enable other women to discover their sexuality. She walked around Berlin in vests embroidered with explicit sexual scenes and the message: Ficken ist Frieden (‘Fucking is peace’). She embroidered nearly 300 garments, treating the gesture as sexual evangelism.

The exhibition ends with pieces from Christopher Kane’s pre-fall 2017 collection; he was inspired by the work of Johann Hauser. The designer visited him at the Haus der Künstler — a uniquely liberal place for artistically active patients to cohabitate at the Maria Gugging psychiatric hospital near Vienna — in 2016. Christopher also sampled drawings by outsider artist Ionel Talpazan (whose work is inspired by UFOs), transforming them into a print. In a similarly collaborative manner, the label Nana Yamazaki works with an organization that promotes outsider art called Atelier Yamanami. “Every year, it’s a collaboration between the artists from the studio and the label. So it’s taking existing outsider art and turning it into a textile,” Yoon He notes.

“My heart is with outsider art because I always have the feeling it’s a necessity that the artist wants to say something to an imaginary viewer,” Yoon He says. “I think a lot of people working with fashion can also be inspired by seeing these strange and personal stories that the clothing arts are telling.”

It’s moving to see garments and accessories made exclusively as irrepressible self-expression. Even limits to people’s agency, psychologically or otherwise, did not stop them from reinventing materials and thinking about what they wanted to convey through what they wore. It confirms as fiercely as anything that the reality of dressing shapes our sense of self.

Credits

Images courtesy of MoMU Fashion Museum and Dr. Guislain Museum.